President Carmichael's Failure to Commit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symbol Institution Volume TJC Vanderbilt University * 1338 KLG

Top Five Borrowers Symbol Institution Volume TJC Vanderbilt University * 1338 KLG University of Louisville 1239 MFM Mississippi State University * 1193 MUM University of Mississippi * 1139 KUDZU-WIDE - OCLC and RAPID Statistics KUK University of Kentucky * 1057 Top Borrowers and Lenders July 2018 - September 2018 * Includes Rapid ILL Counts Top Five Lenders Symbol Institution Volume TKN University of Tennessee * 1764 TJC Vanderbilt University * 1175 EWF Wake Forest University 1154 KUK University of Kentucky * 1127 VRC Virginia Commonwealth * 1021 Top Three Borrowers and Lenders for Each Institution LENDERS #1 #2 #3 AAA Auburn University * TKN 98 KUK 75 LRU 74 ABC University of Alabama at Birmingham* ALM 35 TKN 23 AAA 18 ABH University of AL Lister Hill Health Sci Library* VRC 63 EWF 27 KLG 19 ALM University of Alabama * TKN 86 TJC 60 KUK 49 ERE East Carolina University * TKN 51 VRC 47 FQG 42 EWF Wake Forest University ERE 131 NKM 54 NGU 38 FQG University of Miami * EWF 80 TKN 65 KUK 61 GAT Georgia Inst of Technology VRC 29 VGM 23 LRU 20 KLG University of Louisville ERE 163 KUK 142 TKN 129 KUK University of Kentucky * TKN 266 TJC 226 VRC 93 LRU Tulane University VRC 87 AAA 85 EWF 57 MFM Mississippi State University * TKN 117 AAA 87 TMA 79 MUM University of Mississippi * EWF 128 TKN 121 TMA 115 NGU University of NC at Greensboro ERE 81 NKM 76 TKN 23 NKM University of NC at Charlotte EWF 105 VRC 90 VGM 71 SEA Clemson University TKN 97 KUK 71 EWF 66 SUC/SZR University of South Carolina * TKN 73 TJC 58 ERE 54 TJC Vanderbilt University * TKN -

How Do You Prepare for Something Like the Tragedy at Virginia Tech? the Truth Is, You Don’T

»INSIDE: DAVE ADAMS REMEMBERED • THINK FORWARD HISTORICALLY THE FLAGSHIP PUBLICATION OF COLLEGE MEDIA ADVISERS, INC. • SUMMER/FALL 2007 • VOL. 45 NO. 1-2 MEMORIAL SECTION April 16, 2007 Ross Abdallah Alameddine ✦ Jamie Bishop ✦ Brian Bluhm ✦Ryan Clark ✦ Austin Cloyd ✦ Jocelyne Couture-Nowak ✦ Daniel Perez Cueva ✦ Kevin Granata ✦ Matthew Gregory Gwaltney ✦ Caitlin Hammaren ✦ Jeremy Herbstritt ✦ Rachael Hill ✦Emily Jane Hilscher ✦ Jarrett Lane ✦ Matthew Joseph La Porte ✦ Henry Lee ✦ Liviu Librescu ✦ G.V. Loganathan ✦ Parahi Lumbantoruan ✦ Lauren Ashley McCain ✦ Dan O’Neil ✦ Juan Ortiz ✦ Minal Hiralal Panchal ✦ Erin Peterson ✦ Michael Pohle ✦ Julia Pryde ✦ Mary Read ✦ Reema Samaha ✦ Waleed Mohamed Shaalan ✦ Leslie Sherman ✦ Maxine Turner ✦ Nicole White How do you prepare for something like the tragedy at Virginia Tech? The truth is, you don’t. EDITOR'S CORNER The shock waves from the fatal onslaught at Virginia Tech on April 16 still reverberate through- College Media Review out our society in many forums and on many issues. Few of us can probably really understand the is an official publication of College Media depths of the sorrow that campus community has shared unless, God forbid, a similar tragedy has Advisers Inc. ; however, views expressed within its pages are those of the writers and happened on our own. do not necessarily reflect opinions of the The Virginia Tech tragedy has probably had the greatest collective impact on this generation of organization or of its officers. college students since Sept. 11, 2001, when most of our student journalists were just starting their Any writer submitting articles must follow freshman years of high school. For many of them, the events of April 16 present the dilemma that the Writers Guidelines included on page 31. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Location

UNIVERSITY INFORMATION COACHING STAFF TABLE OF CONTENTS Location ................. Tuscaloosa, Ala. Head Coach .................. Kristy Curry Enrollment ...................... 37,842 Alma Mater . Northeast Louisiana, 1988 INTRODUCTION Founded .................. April 12, 1831 Record at Alabama ....... 116-108 (.518) Athletics Communications Staff .........1 Nickname .................. Crimson Tide Overall Record .......... 425-257 (.623) Quick Facts .........................1 Colors ................ Crimson and White SEC Record ............... 38-74 (.339) Roster .............................2 Conference ................. Southeastern Season at Alabama .............. Eighth Schedule ...........................3 President .................. Dr. Stuart Bell Assistant Coach ............... Kelly Curry Media Information ....................4 Director of Athletics ............ Greg Byrne Alma Mater . Texas A&M, 1990 INTRODUCTION Senior Woman Administrator ... Tiffini Grimes Chancellor Finis E. St. John IV ..........5 Season at Alabama .............. Eighth Faculty Athletics Representative .. Dr. James King Assistant Coach .......... Tiffany Coppage President Dr. Stuart Bell ...............6 Facility ................. Coleman Coliseum Alma Mater . Missouri State, 2009 UA Quick Facts ......................7 Capacity .........................14,474 Season at Alabama ............... Third Director of Athletics Greg Byrne ........8 Assistant Coach ........ Janese Constantine Athletics Administration ...............9 TEAM INFORMATION Alma Mater -

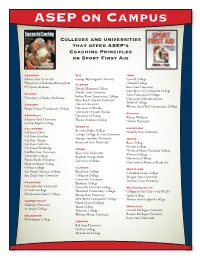

ASEP on Campus

ASEP on Campus Colleges and universities that offer ASEP’s Coaching Principles or Sport First Aid Alabama D.C. Iowa Athens State University George Washington University Cornell College University of Alabama–Birmingham Florida Grinnell College US Sports Academy Florida Memorial College Iowa State University Florida State University Iowa Western Community College Alaska Scott Community College University of Alaska–Anchorage Indian River Community College Palm Beach Atlantic University University of Northern Iowa Waldorf College Arizona Stetson University Western Iowa Tech Community College Prima County Community College University of Florida University of South Florida Kansas Arkansas University of Tampa Kansas Wesleyan Arkansas Tech University Warner Southern College Ottawa University Central Baptist College Georgia California Louisiana Brewton Parker College Cal State–Chico Nicholls State University Georgia College & State University Cal State–East Bay Georgia Southern University Cal State–Fresno Maine Kennesaw State University Cal State–Fullerton Bates College Cal State–Northridge Husson College Idaho Northern Maine Technical College Cal Poly State University Boise State University Concordia College Thomas College Brigham Young–Idaho University of Maine Fresno Pacific University University of Idaho Modesto Junior College University of Maine at Presqe Isle Ohlone College Illinois Maryland San Diego Christian College Blackburn College Columbia Union College San Diego State University College of DuPage Morgan State University Concordia University Salisbury State University Colorado Elmhurst College Colorado State University Greenville Christian College Massachusetts Ft. Lewis College Heartland Community College College of Our Lady of the ELMS Northeastern Junior College Illinois State University Smith College John Wood Community College Connecticut Western New England College North Central College Gallaudet University Triton College Michigan St. -

TULANE Vs. ALABAMA Lute~E Ta Uti ME OUT" with Johnny Lynch WWL Thursdays 9:45 to 10 P.M • • Uworld of SPORTS"

TULANE vs. ALABAMA Lute~e ta uTI ME OUT" with Johnny Lynch WWL Thursdays 9:45 to 10 P.M • • uWORLD OF SPORTS". with Bill Brengel JACKSON BREWING CO. WWL thru Sat. 5:35 5:45 P.M. NEW ORLEANS. LA. Mon. to Tulane Stadium Vol. 18 T H E - c;·~· R EE N I E No. Official Souvenir F oot/,all Program of Tulane University CONTENTS Page Editorial . 3 The Presidents . 5 Tulane Yells . 6 Tulane Roster . 7 Cam-Pix . ............ 9-12, 17-20 National Starting Lineups . .... 14-15 Advertising SEC Schedules . 21 Representatives Alabama Roster ......... 22-23 Football Publi Co-Editors, This is Alabama .. .... .. 2!:: cations, Inc Tulane Songs . 26 370 Lexington A venue ANDY RoGERS Pigskin Roundup 27 New York, N. Y. BILL ]8HNSTON Football Ticket ••• plus your MB Label-of-Quality! Now. as always. Maison Blanche has the line-up of the famous labels you want and buy with confidence. No matter what the occasion ••• MB has the right clothes • • • on one of its famous fashion floors . • MAISON BLANCIIE GREATEST STORE SOUTH 2 IT'S THAT TIME AGAIN Lay aside your baseball bats, store that classed as "perhaps too light for this flannel in moth balls, swap those low quar league," But what they may lack in ter shoes for high tops-it's football time weight, Frnka believes, may be added in again! · that synonym for the 20th century- speed. Yes sir, you may read about the World Veterans of many a Green Wave battle Series and the number of home runs by will be back-Seniors like Emile O'Brien Joe DiMaggio and the records set during and Don Fortier, juniors such as speed the past baseball season. -

Magnolia News Issue, May 2021

MAGNOLIA NEWS MAY, 2021 * VOLUME 23, ISSUE 9 www.vanderbilt.edu/vwc The Vanderbilt Woman’s Club brings together the women of Vanderbilt University; provides an opportunity for intellectual, cultural and social activities within the community and the University; supports and assists the mission of the University; and Members of the Board sponsors the Vanderbilt Woman’s Club Stapleton/Weaver Endowed Scholarship through fundraising. 2020-2021 Tracy Stadnick President’s Letter President Ahh Spring! How “mud-luscious” and “puddle-wonderful” as E.E. Cummings Joy Allington-Baum stated in one of my favorite poems “in Just-”. What are your favorite Past President poems? What words resonate with you? Join us to hear Kate Daniels, Vanderbilt’s professor of poetry, present the “Curious Power of Poetry” Sharon Hels on May 10th. Vice President/Programs We are hosting our first “Meet and Three” Food Drive for Second Harvest Elisabeth Sandberg Food Bank on May 15th. You will “meet” VWC friends and donate “Meat and Treasurer Three” food. Bring your food donation to Kelly Chamber’s house with a drive- thru food drop off. We encourage you to collect donations from your neighbors to bring along. Thank you for helping. Ebbie Redwine Recording Secretary Lunch Bunch, Book Clubs, Music group, Antiques, MahJongg, Cribbage, Garden Club and Chocolate Lovers are meeting on zoom or in person while Sara Plummer following VU COVID guidelines. Read the newsletter to see dates and times. Corresponding Secretary Read Joy Allington-Baum’s article, “From the Archives,” and discover our Kelly Chambers fascinating history and its connection with Magnolia trees on campus. -

Archived 2011/2012 Undergraduate Catalog

Catalog 2011/2012 Archived Undergraduate Vanderbilt University Undergraduate Catalog Calendar 2011/2012 FALL SEMESTER 2011 Deadline to pay fall charges / Wednesday 17 August Orientation begins for new students / Saturday 20 August Classes begin / Wednesday 24 August Registration ends / Tuesday 30 August, 11:59 p.m. Family Weekend / Friday 16 September–Sunday 18 September Fall break / Thursday 6 October–Friday 7 October Homecoming and related activities / Monday 17 October–Saturday 22 October Thanksgiving holidays / Saturday 19 November–Sunday 27 November Classes end / Thursday 8 December Reading days and examinations / Friday 9 December–Saturday 17 December Fall semester ends / Saturday 17 December SPRING SEMESTER 2012 Deadline to pay spring charges / Thursday 5 January Classes begin / Monday 9 January Registration ends / Sunday 15 January, 11:59 p.m. Spring holidays / Saturday 3 March–Sunday 11 March Classes end / Monday 23 April Reading days and examinations / Tuesday 24 April–Thursday 3 May Commencement / Friday 11 May MAYMESTER 2012 Classes begin / Monday 7 May Classes end; examinations / Friday 1 June Catalog SUMMER SESSION 2012 Classes begin in Arts and Science, Blair, and Engineering2011/2012 / Tuesday 5 June Module I begins in Peabody / Monday 11 June Examinations for first-half courses / Friday 6 July Second-half courses begin / Tuesday 10 July Examinations for second-half and full-term summer courses / Friday 10 August Archived Undergraduate Undergraduate Catalog College of Arts and Science Blair School of Music School of Engineering -

Social Studies

201 OAlabama Course of Study SOCIAL STUDIES Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education • Alabama State Department of Education For information regarding the Alabama Course of Study: Social Studies and other curriculum materials, contact the Curriculum and Instruction Section, Alabama Department of Education, 3345 Gordon Persons Building, 50 North Ripley Street, Montgomery, Alabama 36104; or by mail to P.O. Box 302101, Montgomery, Alabama 36130-2101; or by telephone at (334) 242-8059. Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education Alabama Department of Education It is the official policy of the Alabama Department of Education that no person in Alabama shall, on the grounds of race, color, disability, sex, religion, national origin, or age, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment. Alabama Course of Study Social Studies Joseph B. Morton State Superintendent of Education ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION STATE SUPERINTENDENT MEMBERS OF EDUCATION’S MESSAGE of the ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Dear Educator: Governor Bob Riley The 2010 Alabama Course of Study: Social President Studies provides Alabama students and teachers with a curriculum that contains content designed to promote competence in the areas of ----District economics, geography, history, and civics and government. With an emphasis on responsible I Randy McKinney citizenship, these content areas serve as the four Vice President organizational strands for the Grades K-12 social studies program. Content in this II Betty Peters document focuses on enabling students to become literate, analytical thinkers capable of III Stephanie W. Bell making informed decisions about the world and its people while also preparing them to IV Dr. -

LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Lyceum-The Circle Historic District Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: University Circle Not for publication: City/Town: Oxford Vicinity: State: Mississippi County: Lafayette Code: 071 Zip Code: 38655 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: X Public-State: X Site: ___ Public-Federal: Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 8 buildings buildings 1 sites sites 1 structures structures 2 objects objects 12 Total Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: ___ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Collegian 2012.Indd

CollegianThis is how college is meant to be. Scholar, Teacher, Mentor: Trudier Harris Returns Home By Kelli Wright Coming home at the end of a long journey is a theme that DR. TRUDIER HARRIS has contemplated, taught, and writ- ten about many times in her award-winning books and in the classroom. Recently, Harris found herself in the midst of her own home- coming, the central character in a narrative that is a familiar part of southern life and literature. When she retired from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she was the J. Carlyle Sitterson Professor of English, she was not looking for other work. But her homecoming resulted in an unexpected “sec- ond career” as a professor in the College’s Department of English and a chance to explore new intellectual territories. In addition, it has meant a return to many of the places of her youth, this time in the role of change agent. Raised on an 80-acre cotton farm in Greene County, Ala., Harris was the sixth of nine children. Though her parents had to work hard to make ends meet, they always stressed the impor- tance of education. Harris attended Tuscaloosa’s 32nd Avenue Elementary School, now known as Martin Luther King Elementary School. In the late 1960s she entered Stillman College in Tuscaloosa. Initially she considered a career as a physical educa- tion teacher or a psychiatrist. But losing an intramural race to a young woman who was half as tall as she dampened her desire to teach PE, and the realization that she did not want to listen to people’s problems soured her plans in psychiatry. -

Commencement Guide

COMMENCEMENT GUIDE MAY | 2019 FROM THE PRESIDENT To the families of our graduates: What an exciting weekend lies ahead of you! Commencement is a special time for you to celebrate the achievements of your student. Congratulations are certainly in order for our graduates, but for you as well! Strong support from family allows our students to maximize their potential, reaching and exceeding the goals they set. As you spend time on our campus this weekend, I hope you will enjoy seeing the lawns and halls where your student has created memories to last a lifetime. It has been our privilege and pleasure to be their home for these last few years, and we consider them forever part of our UA family. We hope you will join them and return to visit our campus to keep this relationship going for years to come. Because we consider this such a valuable time for you to celebrate your student’s accomplishments, my wife, Susan, and I host a reception at our home for graduates and their families. We always look forward to this time, and we would be delighted if you would join us at the President’s Mansion from 1:00 to 3:00 p.m. on Friday, May 3. Best wishes for a wonderful weekend, and Roll Tide! Sincerely, Stuart R. Bell SCHEDULE OF EVENTS All Commencement ceremonies will take place at Coleman Coliseum. FRIDAY, MAY 3 Reception for graduates and their families Hosted by President and Mrs. Stuart R. Bell President’s Mansion Reception 1:00 - 2:00 p.m. -

TRIAL INNOVATION NETWORK Team Roster

TRIAL INNOVATION NETWORK Team Roster Trial Innovation Center – Duke University/Vanderbilt University Danny Benjamin Michael DeBaun Julie Ozier Principal Investigator Vanderbilt Investigator Representative C-IRB Lead Duke University Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Gordon Bernard Jennifer Dix JoAnna Pomerantz Co-Principal Investigator Admin Support- Website Sr. Associate Contracts Management Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt University Duke University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Lori Poole Julia Dunagan Renee Pridgen Lead Program Manager Admin Support- Website Director, Clinical Operations Duke University Vanderbilt University Duke University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Terri Edwards Aimee Edgeworth Jill Pulley Admin Lead Admin Support Executive Director Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Rebecca Abel Shelby Epps Libby Salberg C-IRB Lead Admin Support-Master Agreements Master Agreements Project Lead Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Leslie Amos Davera Gabriel Emily Sheffer Project Lead Senior Informaticist Admin Support- Central IRB Duke University Duke University Vanderbilt University [email protected] [email protected]