PAPER to BE PRESENTED at 11Th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property, Ubud Bali Indonesia, June 19-June 23, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rapid Assessment on the Trade in Marine Turtles in Indonesia, Malaysia and Viet Nam Lalita Gomez Kanitha Krishnasamy Stealthc4 \ Dreamstime \ Stealthc4

NOVEMBER 2019 A Rapid Assessment on the Trade in Marine Turtles in Indonesia, Malaysia and Viet Nam Lalita Gomez Kanitha Krishnasamy stealthc4 \ dreamstime stealthc4 \ TRAFFIC REPORT A Rapid Assessment on the Trade in Marine Turtles in Indonesia, Malaysia and Viet Nam TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. \dreamstime stealthc4 The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organisations con- cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published by TRAFFIC, Southeast Asia Regional Ofce, Suite 12A-01, Level 12A, Tower 1, Wisma AmFirst, Jalan Stadium SS 7/15, 47301 Kelana Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 © TRAFFIC 2019. Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-85-5 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722 Suggested citation: Gomez, L. and Krishnasamy, K. (2019). A Rapid Assessment on the Trade in Marine stealthc4 \dreamstime stealthc4 Turtles in Indonesia, Malaysia and Viet Nam. TRAFFIC. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia. Green Sea Turtle Chelonia mydas © Willyambradberry/ Dreamstime.com Design by Faril Izzadi Mohd Noor This communication has been produced under contract to CITES and with the fnancial assistance of the European Union. -

399 International Court of Justice Case Between Indonesia And

International Court of Justice Case between Indonesia and Malaysia Concerning Sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan Introduction On 2 November 1998 Indonesia and Malaysia jointly seised the International Court of Justice (ICJ) of their dispute concerning sovereignty over the islands of Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan in the Celebes Sea.' They did so by notifying the Court of a Special Agreement between the two states, signed in Kuala Lumpur on 31 May 1997 and which entered into force on 14 May 1998 upon the exchange of ratifying instruments. In the Special Agreement, the two parties request the Court "to determine on the basis of the treaties, agreements and other evidence furnished by [the two parties], whether sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan belongs to the Republic of Indonesia or Malaysia". The parties expressed the wish to settle their dispute "in the spirit of friendly relations existing between [them] as enunciated in the 1976 Treaty of Amity and Co-operation in Southeast Asia" and declared in advance that they will "accept the Judgement of the Court given pursuant to [the] Special Agreement as final and binding upon them." On 10 November 1998 the ICJ made an Order' fixing the time limits for the respective initial pleadings in the case as follows: 2 November 1999 for the filing by each of the parties of a Memorial; and 2 March 2000 for the filing of the counter-memorials. By this order the Court also reserved subsequent procedure on this case for future decision. In fixing the time limits for the initial written pleadings, the Court took account and applied the wishes expressed by the two parties in Article 3, paragraph 2 of their Special Agreement wherein they provided that the written pleadings should consist of: 1 International Court of Justice, Press Communique 98/35, 2 November 1998. -

Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA

United Nations UNEP/GEF South China Sea Global Environment Environment Programme Project Facility NATIONAL REPORT on Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA Mr. Abdul Rahim Bin Gor Yaman Focal Point for Coral Reefs Marine Park Section, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Level 11, Lot 4G3, Precinct 4, Federal Government Administrative Centre 62574 Putrajaya, Selangor, Malaysia NATIONAL REPORT ON CORAL REEF IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA – MALAYSIA 37 MALAYSIA Zahaitun Mahani Zakariah, Ainul Raihan Ahmad, Tan Kim Hooi, Mohd Nisam Barison and Nor Azlan Yusoff Maritime Institute of Malaysia INTRODUCTION Malaysia’s coral reefs extend from the renowned “Coral Triangle” connecting it with Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and Australia. Coral reef types in Malaysia are mostly shallow fringing reefs adjacent to the offshore islands. The rest are small patch reefs, atolls and barrier reefs. The United Nations Environment Programme’s World Atlas of Coral Reefs prepared by the Coral Reef Unit, estimated the size of Malaysia’s coral reef area at 3,600sq. km which is 1.27 percent of world total coverage (Spalding et al., 2001). Coral reefs support an abundance of economically important coral fishes including groupers, parrotfishes, rabbit fishes, snappers and fusiliers. Coral fish species from Serranidae, Lutjanidae and Lethrinidae contributed between 10 to 30 percent of marine catch in Malaysia (Wan Portiah, 1990). In Sabah, coral reefs support artisanal fisheries but are adversely affected by unsustainable fishing practices, including bombing and cyanide fishing. Almost 30 percent of Sabah’s marine fish catch comes from coral reef areas (Department of Fisheries Sabah, 1997). -

Sabah 90000 Tabika Kemas Kg

Bil Nama Alamat Daerah Dun Parlimen Bil. Kelas LOT 45 BATU 7 LORONG BELIANTAMAN RIMBA 1 KOMPLEKS TABIKA KEMAS TAMAN RIMBAWAN Sandakan Sungai SiBuga Libaran 11 JALAN LABUKSANDAKAN SABAH 90000 TABIKA KEMAS KG. KOBUSAKKAMPUNG KOBUSAK 2 TABIKA KEMAS KOBUSAK Penampang Kapayan Penampang 2 89507 PENAMPANG 3 TABIKA KEMAS KG AMAN JAYA (NKRA) KG AMAN JAYA 91308 SEMPORNA Semporna Senallang Semporna 1 TABIKA KEMAS KG. AMBOI WDT 09 89909 4 TABIKA KEMAS KG. AMBOI Tenom Kemabong Tenom 1 TENOM SABAH 89909 TENOM TABIKA KEMAS KAMPUNG PULAU GAYA 88000 Putatan 5 TABIKA KEMAS KG. PULAU GAYA ( NKRA ) Tanjong Aru Putatan 2 KOTA KINABALU (Daerah Kecil) KAMPUNG KERITAN ULU PETI SURAT 1894 89008 6 TABIKA KEMAS ( NKRA ) KG KERITAN ULU Keningau Liawan Keningau 1 KENINGAU 7 TABIKA KEMAS ( NKRA ) KG MELIDANG TABIKA KEMAS KG MELIDANG 89008 KENINGAU Keningau Bingkor Keningau 1 8 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) KG KUANGOH TABIKA KEMAS KG KUANGOH 89008 KENINGAU Keningau Bingkor Keningau 1 9 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) KG MONGITOM JALAN APIN-APIN 89008 KENINGAU Keningau Bingkor Keningau 1 TABIKA KEMAS KG. SINDUNGON WDT 09 89909 10 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) KG. SINDUNGON Tenom Kemabong Tenom 1 TENOM SABAH 89909 TENOM TAMAN MUHIBBAH LORONG 3 LOT 75. 89008 11 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) TAMAN MUHIBBAH Keningau Liawan Keningau 1 KENINGAU 12 TABIKA KEMAS ABQORI KG TANJUNG BATU DARAT 91000 Tawau Tawau Tanjong Batu Kalabakan 1 FASA1.NO41 JALAN 1/2 PPMS AGROPOLITAN Banggi (Daerah 13 TABIKA KEMAS AGROPOLITAN Banggi Kudat 1 BANGGIPETI SURAT 89050 KUDAT SABAH 89050 Kecil) 14 TABIKA KEMAS APARTMENT INDAH JAYA BATU 4 TAMAN INDAH JAYA 90000 SANDAKAN Sandakan Elopura Sandakan 2 TABIKA KEMAS ARS LAGUD SEBRANG WDT 09 15 TABIKA KEMAS ARS (A) LAGUD SEBERANG Tenom Melalap Tenom 3 89909 TENOM SABAH 89909 TENOM TABIKA KEMAS KG. -

Dispute International Between Indonesia and Malaysia Seize on Sipadan and Lingitan Island

DISPUTE INTERNATIONAL BETWEEN INDONESIA AND MALAYSIA SEIZE ON SIPADAN AND LINGITAN ISLAND Nur Fareha Binti Mohamad Zukri International Student of Sultan Agung Islamic University Semarang [email protected] Ong Argo Victoria International Islamic University Malaysia [email protected] Fadli Eko Apriliyanto Sultan Agung Islamic University Semarang [email protected] Abstract In 1998 the issue of Sipadan and Ligitan dispute brought to the ICJ, later in the day Tuesday, December 17, 2002 ICJ issued a decision on the sovereignty dispute case of Sipadan-Ligatan between Indonesia and Malaysia. As a result, in the voting at the institution, Malaysia won by 16 judges, while only one person who sided with Indonesia. Of the 17 judges, 15 are permanent judges of MI, while one judge is an option Malaysia and another selected by Indonesia. Victory Malaysia, therefore under consideration effectivity (Without deciding on the question of territorial waters and maritime boundaries), the British (colonizers Malaysia) has made a real administrative action in the form of the issuance of bird wildlife protection ordinance, a tax levied against turtle egg collection since 1930, and the operation of the lighthouse since the 1960s an. Meanwhile, Malaysia's tourism activities do not be a consideration, as well as the refusal is based on chain of title (a proprietary suite of Sultan of Sulu) but failed to demarcate the sea border between Malaysia and Indonesia in Makassar strait. Keywords: Dispute; International; Island. A. INTRODUCTION Sea is one of the natural resources that can be utilized by humans through the country to meet and realize the people's welfare. -

A Sabah Gazetteer

A Sabah Gazetteer Copyright © Sabah Forestry Department and Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM), 1995 Forest Research Centre, Forestry Department, Sabah, Malaysia First published 1995 A Sabah Gazetteer by Joseph Tangah and K.M. Wong ISBN 983–9592–36–X Printed in Malaysia by Print Resources Sdn. Bhd., 47301 Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan A Sabah Gazetteer Joseph Tangah and K.M. Wong Forest Research Centre, Forestry Department, Sabah, Malaysia Published by Sabah Forestry Department and Forest Research Institute Malaysia 1995 Contents Page Foreword vii Introduction 1 Acknowledgements 2 PART 1. Human Settlements 3 PART 2. Hill and Mountain Peaks 24 PART 3. Mountain Ranges 27 PART 4. Islands 30 PART 5. Rivers and Streams 39 PART 6. Roads 81 PART 7. Forest Reserves, Wildlife Reserves and Protected Areas 98 Foreword In the endeavour to prepare a Tree Flora for the botanically rich states of Sabah and Sarawak in Malaysian Borneo, one of the main concerns has also been to assemble an uptodate data base which incorporates information on species. It was at once realised that this opportunity comes handinhand with information from numerous specimens that will be made available by specialists involved in the project, making the data set as scientifically sound as can be. This gazetteer is one of those steps towards such a specialised data base, tabulating information that serves as a primordial vocabulary on localities within that data base. By itself, too, the gazetteer will be a handy reference to all who are concerned with the scientific and systematic management of natural resources and land use in Sabah, and in the development of geographical information systems. -

Sipadan and Ligitan Island Dispute: Victory Gained by Malaysia Against Indonesia in the International Court of Justice in the Principle of Effectivité (2002)

SIPADAN AND LIGITAN ISLAND DISPUTE: VICTORY GAINED BY MALAYSIA AGAINST INDONESIA IN THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE IN THE PRINCIPLE OF EFFECTIVITÉ (2002) By DHARMA SATRYA 016201300180 A thesis presented to the Faculty of Humanities, International Relations Study Program President University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Bachelor Degree in International Relations Major in Diplomatic Studies 2018 1 2 3 ABSTRACT Title: Sipadan And Ligitan Island Dispute: Victory Gained By Malaysia Against Indonesia In The International Court of Justice In The Matter Of Effectivité (2002) The dispute between The Republic of Indonesia with The Republic of Malaysia for the Islands of Sipadan and Ligitan is one of the key cases that defined how territorial dispute settlements is studied in the world of International Relations. This research analyzes the decision by the International Court of Justice in determining the dispute for the Sipadan and Ligitan Islands. After all the key arguments brought by both states, the International Court of Justice decided the ruling to favor Malaysia by the principle of effectivité. This thesis will elaborate how Malaysia’s effectivité was the key to the decision. In addition, this thesis will analyze the interest of Malaysia to dispute the ownership of the islands, based on neorealism. This research was conducted from September of 2017 until March of 2018. The research process was conducted by the qualitative analysis, supported by sources from books, journals, and news articles. Keywords: Republic of Indonesia, Republic of Malaysia, Sipadan - Ligitan Islands, Territorial Dispute, Effectivité. 4 ABSTRAK Title: Sipadan And Ligitan Island Dispute: Victory Gained By Malaysia Against Indonesia In The International Court of Justice In The Matter Of Effectivité (2002) Sengketa wilayah antara Republik Indonesia dengan Republik Malaysia untuk kepemilikan atas Kepulauan Sipadan - Ligitan adalah salah studi kasus mengenai sengketa wilayah di dunia hubungan internasional. -

Case Concerning Sovereignty Over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING SOVEREIGNTY OVER PULAU LIGITAN AND PULAU SIPADAN OBSERVATIONS OF MALAYSIA ON THE APPLICATION FOR PERMISSION TO INTERVENE BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES 2 MAY 2001 CASE CONCERNING SOVEREIGNTY OVER PULAU LIGITAN AND PULAU SIPADAN (INDONESIA/MALAYSIA) Written Observations of Malaysia on the Application for permission to intervene by the Government of the Republic of the Phiiippines Introduction 1. These written observations are made by Malaysia in response to the Registrar's letter of 14 March 2001. 2. To summarize, Malaysia categorically rejects any attempt of the Philippines to concern itself with a territorial dispute involving two small islands off the coast of Sabah (formerly North Bomeo). The subject of the dispute between Indonesia and Malaysia is not Malaysia's sovereignty over the State of Sabah (which sovereignty Indonesia explicitly accepts and recognises). It is solely the question of title to two small islands off Semporna, Malaysia. Indonesia's claim is based on an interpretation of Article TV of the Convention of 1891 between Great Britain and the Netherlands. Spain had previously expressly recognised British title over the territory which was the subject of the 1891 Convention, by Article IJJ of the Protocol of 1885.' The Philippines can have no greater rights than Spain had. The interpretation of the 1891 Convention is thus a matter exclusively between Indonesia and Malaysia, in which the Philippines can have no legal interest. Nor does the Philippines have any legal interest in the subject matter of the specific dispute submitted to the Court by the Special Agreement. -

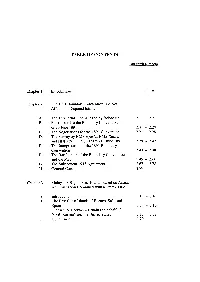

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraoh numbers Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 - 1.10 Chapter 2 The 1891 Boundary Convention Did Not Affect the Disputed Islands The Territorial Title Alleged by Indonesia Background to the Boundary Convention of 20 June 189 1 The Negotiations for the 189 1 Convention The Survey by HMS Egeria, HMS Rattler and HNLMS Banda, 30 May - 19 June 1891 The Interpretation of the 189 1 Boundary Convention The Ratification of the Boundary Convention and the Map The Subsequent 19 15 Agreement General Conclusions Chapter 3 Malaysia's Right to the Islands Based on Actual Administration Combined with a Treaty Title A. Introduction 3.1 - 3.4 B. The East Coast Islands of Borneo, Sulu and Spain 3.5 - 3.16 C. Transactions between Britain (on behalf of North Borneo) and the United States 3.17 - 3.28 D. Conclusion 3.29 Chapter 4 The Practice of the Parties and their Predecessors Confirms Malaysia's Title A. Introduction B. Practice Relating to the Islands before 1963 C. Post-colonial Practice D. General Conclusions Chapter 5 Officia1 and other Maps Support Malaysia's Title to the Islands A. Introduction 5.1 - 5.3 B. Indonesia's Arguments Based on Various Maps 5.4 - 5.30 C. The Relevance of Maps in Determining Disputed Boundaries 5.31 - 5.36 D. Conclusions from the Map Evidence as a Whole 5.37 - 5.39 Submissions List of Annexes Appendix 1 The Regional History of Northeast Bomeo in the Nineteenth Century (with special reference to Bulungan) by Prof. Dr. Vincent J. H. Houben Table of Inserts Insert Descri~tion page 1. -

Status of Coral Reefs in Malaysia, 2018

Status of Coral Reefs in Malaysia, 2018 Reef Check Malaysia Contents Executive Summary 1 1 Introduction 2 2 Reef Check 3 2.1 Background 3 2.2 Survey Methodology 3 2.3 Survey Sites 4 3 2018 Survey Results & Analysis 5 3.1 Status of Coral Reefs in Malaysia 2018 5 3.2 Status of Coral Reefs in Key Eco-regions in Malaysia 10 4 Twelve Years of Reef Check Data 68 4.1 Peninsular versus East Malaysia over 12 Years 68 4.2 Changing Reef Health in Selected Areas 72 5 Summary and Recommendations 81 5.1 Summary 81 5.2 Recommendations 82 5.3 Conclusion 84 Acknowledgements 85 References 88 Appendix 1: 2018 Survey Sites 89 Saving Our Reefs Research, Education, Conservation Executive Summary 1. A total of 212 sites were surveyed in 2018 (2017: 227), 95 in Peninsular Malaysia and 117 in East Malaysia. The surveys are a continuation of a successful National Reef Check Survey Programme that has now run for twelve years. 2. The surveys were carried out by trained volunteers as well as government officials from the Department of Marine Parks Malaysia and Sabah Parks, reflecting commitment from the Government in further improving management of Malaysia’s coral reefs. Surveys were carried out on several islands off Peninsular Malaysia’s East and West coast, covering both established Marine Protected Areas and non- protected areas, and in various parts of East Malaysia, both Sabah and Sarawak. 3. The results indicate that Malaysian reefs surveyed have a relatively high level of living coral, at 42.42% (2017: 42.53%). -

Yachting Destinations Off the Beaten Path of Malaysia's Eastern Coast

Features EAST COAST EXPLORATIONS Yachting destinations off the beaten path of Malaysia’s eastern coast and Borneo may be considered new cruising grounds by many superyacht captains, but these destinations are definitely fast becoming favorites for superyachts due to the region’s unique natural beauty and adventure-tapped itineraries. 56 Yanneke Too – taken in Borneo. The 36m S/y Yanneke Too is a beautifully designed luxury superyacht launched in 1995. Charles Dwyer oversaw her early design stages with the owner and has been her captain ever since. Fourth Quarter 2011 57 Features Borneo Sabah sunset he west coast of Peninsula Malaysia is relatively Kota Kinabalu, there’s Sipidan, Kapalai and Lankayan well travelled and documented by cruising on the east coast, and Banggi and Balambangan on superyachts, but the east coast - Sarawak and the north coast. All of these islands (and many more) TSabah, Borneo - offer an all together more adventurous offer the serious and amateur diver alike a huge array of prospect. These largely unexplored cruising grounds underwater attractions. include some of the most spectacular and beautiful waters in South East Asia, with islands and mainland Borneo’s treasures attractions that rival best in the world. The east coast of Borneo is one of the most diverse cruising play- Malaysia fringes the South China Sea, offering crystal grounds in the world and allows visitors to combine az- seas and pristine white sand beaches framing dozens ure waters, tropical islands, and mainland coastal bays of picturesque islands. with an extraordinarily diverse selection of mainland Cruising grounds in three countries are eas- beauty. -

Sipadan-Kapalai Dive Resort, Sabah

SIPADAN-KAPALAI DIVE RESORT, SABAH Package Malaysian & Residence Non-Malaysian Rate Per Person Diver Non-diver Children Diver Non-diver Children 3D2N RM 1740 RM 1392 RM 696 RM2050 RM 1640 RM 820 4D3N RM 2350 RM 1880 RM 940 RM 2860 RM 2288 RM 1144 5D4N RM 3120 RM 2496 RM 1248 RM 3760 RM 3008 RM 1504 6D5N RM 3890 RM 3112 RM 1556 RM 4660 RM 3728 RM 1864 7D6N RM 4660 RM 3728 RM 1864 RM 5560 RM 4448 RM 2224 Extension Night RM 770 RM 616 RM 360 RM 900 RM 720 RM 360 PACKAGE RATES INCLUSIVE: Return land transfer Tawau Airport to Semporna Jetty Return boat transfer Semporna Jetty to Kapalai Resort Fresh food cooked by our Chef on buffet style Afternoon snacks, tea/coffee and cordial served throughout the day DIVING PACKAGE RATES INCLUSIVE: 3 boat dives daily except on arrival and departure days Guest staying in Semporna or Tawau on the last day will be provide one dive only (Strictly NO fly policy within 24hours after the last dive) Unlimited dive in front of Kapalai Dive Centre Tank, weight and weight belt provided No extra charge for night dives in front of dive centre for advanced diver or diver with night dive experience only DIVING NOTE: Diving package does not guarantee an opportunity to dive in Sipadan! The resort will apply for guest entry to this restricted area and should there be an approval in any of the day, the dive to Sipadan will be free of charge. The chances to dive Sipadan are higher if the duration of stay is 3 nights or more.