Gideon Haigh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scoresheet NEWSLETTER of the AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY INC

scoresheet NEWSLETTER OF THE AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY INC. www.australiancricketsociety.com.au Volume 38 / Number 2 /AUTUMN 2017 Patron: Ricky Ponting AO WINTER NOSTALGIA LUNCHEON: Featuring THE GREAT MERV HUGHES Friday, 30 June, 2017, 12 noon for a 12.25 start, The Kelvin Club, Melbourne Place (off Russell Street), CBD. COST: $75 – members & members’ partners; $85 – non-members. TO GUARANTEE YOUR PLACE: Bookings are essential. This event will sell out. Bookings and moneys need to be in the hands of the Society’s Treasurer, Brian Tooth at P.O. Box 435, Doncaster Heights, Vic. 3109 by no later than Tuesday, 27 June, 2017. Cheques should be made payable to the Australian Cricket Society. Payment by electronic transfer please to ACS: BSB 633-000 Acc. No. 143226314. Please record your name and the names of any ong-time ACS ambassadors Merv Hughes is guest of honour at our annual winter nostalgia luncheon at the guests for whom you are Kelvin Club on Friday, June 30. Do join us for an entertaining afternoon of reminiscing, story-telling and paying. Please label your Lhilariously good fun – what a way to end the financial year! payment MERV followed by your surname – e.g. Merv remains one of the foremost personalities in Australian cricket. His record of four wickets per Test match and – MERVMANNING. 212 wickets in all Tests remains a tribute to his skill, tenacity and longevity. Standing 6ft 4in in the old measure Brian’s phone number for Merv still has his bristling handle-bar moustache and is a crowd favourite with rare people skills. -

Issue 43: Summer 2010/11

Journal of the Melbourne CriCket Club library issue 43, suMMer 2010/2011 Cro∫se: f. A Cro∫ier, or Bi∫hops ∫taffe; also, a croo~ed ∫taffe wherewith boyes play at cricket. This Issue: Celebrating the 400th anniversary of our oldest item, Ashes to Ashes, Some notes on the Long Room, and Mollydookers in Australian Test Cricket Library News “How do you celebrate a Quadricentennial?” With an exhibition celebrating four centuries of cricket in print The new MCC Library visits MCC Library A range of articles in this edition of The Yorker complement • The famous Ashes obituaries published in Cricket, a weekly cataloguing From December 6, 2010 to February 4, 2010, staff in the MCC the new exhibition commemorating the 400th anniversary of record of the game , and Sporting Times in 1882 and the team has swung Library will be hosting a colleague from our reciprocal club the publication of the oldest book in the MCC Library, Randle verse pasted on to the Darnley Ashes Urn printed in into action. in London, Neil Robinson, research officer at the Marylebone Cotgrave’s Dictionarie of the French and English tongues, published Melbourne Punch in 1883. in London in 1611, the same year as the King James Bible and the This year Cricket Club’s Arts and Library Department. This visit will • The large paper edition of W.G. Grace’s book that he premiere of Shakespeare’s last solo play, The Tempest. has seen a be an important opportunity for both Neil’s professional presented to the Melbourne Cricket Club during his tour in commitment development, as he observes the weekday and event day The Dictionarie is a scarce book, but not especially rare. -

Annual Report 2016-2017

2 PARRAMATTA DISTRICT CRICKET CLUB INC 1843 – 2017 You are cordially invited to attend the ANNUAL MEETING of the above Club to be held at the Viking Sports Club, (Scandia Room) 35 Quarry Road (opposite Curtis Oval) Dundas Valley NSW 2117 On Friday 28th July 2017 at 6.30 pm. BUSINESS 1. To receive the 120th Annual Report 2. Any Notices of Motion According to Rules 3. Life Membership Award 4. To elect Officers and Committee 5. Election of Vice Presidents 6. To transact any business which may be introduced to Rule Only Financial Members of the previous season shall be entitled to vote (vide by laws) R. Wright OAM P O Box 143 Honorary Secretary PARRAMATTA NSW 2124 Phone: 0416 056 038 www.parracricket.com.au [email protected] 3 PARRAMATTA DISTRICT CRICKET CLUB INC. PO Box 143, PARRAMATTA 2124 OFFICE BEARERS 2016-2017 JOINT PATRONS Federal Member for Parramatta Ms. Julie Owens State Member for Parramatta Geoff Lee City of Parramatta Council Cumberland Council K.D. Walters MBE Parramatta Leagues Club President Parramatta District Cricket Association Alan Overton AM PRESIDENT Mr. Greg Monaghan DEPUTY PRESIDENT Mr. P West HONORARY SECRETARY Mr. R Wright OAM HONORARY TREASURER Mr. T Wood MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE P Sullivan R Cherry B Cherry P Calvert P Copperfield SELECTION COMMITTEE Chairman Paul Sullivan 1st Grade: Nick Bertus Jason Coleman Paul Sullivan 2nd Grade: Luke Dempsey Jason Coleman Paul Sullivan 3rd Grade: Jason Coleman Jason Coleman Paul Sullivan 4th Grade: Kevin Tyler Jason Coleman Paul Sullivan 5th Grade: Mark McLeod Jason Coleman Paul Sullivan PROVISIONAL SELECTION COMMITTEE Chairman Tom Wood B. -

AMICUS Newsletter

AMICUS MAY 2019 Vol 46 No 2 Journal of the B S H S Past Students’ Association Inc. HERITAGE LISTING Brisbane State High School is a place that satisfies numerous criteria of the Queensland Heritage Act 1992. With its core built in 1864 and opened in 1865 as the South Brisbane Primary School, Block “H” was the South Brisbane Intermediate School from 1929 to 1953. Block “H” was transferred to Brisbane State High School in 1964 and was added to the Queensland Heritage Register in 1994. In November 2018 the Red Brick Building, Block “A” and three significant fig trees on the Merivale Campus alias The Farm were added to the Heritage Register. The Statement of Significance states: “Block “A”, (1925) the first purpose-built state high school built in Brisbane, is one of the earliest schools in Queensland not attached to a technical college. It illustrates the Queensland Government’s commitment to state-provided secondary education. Block “A” is an excellent, intact example of an Urban Brick School Building designed by the Department of Public Works (DPW). It is important in demonstrating the principal charac- teristics of this type, which include: a handsome edifice standing in a prominent location; symmetrical two-storey form of classrooms and teachers rooms above an understorey of open play spaces; a linear layout of the main floors with rooms accessed by corridors; loadbearing masonry construction; prominent projecting central entrance bay; and a high standard of design to provide superior educational environments that focus on abundant natural light and ventilation. It demonstrates the use of stylistic features of its era, through its roof form, joinery and decorative treatment. -

Libs Revolt After Poll Drubbing

06 NEWS MONDAY NOVEMBER 26 2018 Libs revolt after poll Cricket drubbing VICTORIAN Liberal Party president Michael Kroger is rebuffing calls for him to resign deal’s a after the party’s state election obliteration – but Labor Prem- ier Daniel Andrews is backing him all the way. Former Victorian premier Jeff Kennett spectacularly called for Mr Kroger to resign big hit on live television before mid- night on Saturday, a sugges- tion Mr Kroger was quick to THE 2018 cricket season is they don’t miss a single ball or rebuke. well underway with the first over this summer. Speaking on ABC’s Insiders Domain Test set to air on De- The Fox Cricket App helps program yesterday, Mr An- cember 6 when a new gener- you keep up to date with latest drews took a pointed swipe at ation of Australian cricket news from each team, scores, his political opponents. stars don the Baggy Green to as well as the best video, high- “Swanning around the sub- take on world No. 1 Test crick- lights and match vision for urbs that you’ve never been to et team, India. each game. in your Burberry trench coat Foxtel’s new dedicated Cricket fans can download lecturing people about the cost cricket channel, Fox Cricket, the Fox Cricket app for iPhone of living – people pick fakes will be there and broadcasting and Android Smartphone de- and they pick nasty fakes from 24 hours a day with a feast of vices from the App Store and a long way off,” Mr Andrews cricket for every Aussie fan, Google Play store and Foxtel said. -

Rostrevor--Magazine-March-2012.Pdf

rostrevor A Catholic School in the Edmund Rice Tradition March 2012 ROSTREVOR COLLEGE inside Palma Merenti Chair of the Board From the Headmaster Senior Years Middle Years Junior Years Scholastic Highlights Red and Black ROCCC Elders’ Lunch 2011 1976 Reunion John McInnes Reflects Butch Harding Obituary 1981 Reunion KOK Willowfest ROCFC ROCSC In Memoriam QUARTERLY Print Post Approved PPP 535216-00029 Rostrevor College Glen Stuart Road, Woodforde South Australia 5072 Telephone 08 8364 8200 Facsimile 08 8364 8396 email [email protected] www.rostrevor.sa.edu.au 2 Palma Merenti From the Outgoing Chairperson 2011 Isn’t it strange that we admire The elephant gets another gig in that College and community facilities in the innovation yet often feel uncomfortable we also talk of the elephant in the form of an Early Learning & in the face of change and unwilling to room or (as George Clooney says) the Development Centre and Sports & take risks? Risk taking, after all, is a moose in the room. Meaning a problem Aquatic Centre on the Magill Secure pre-condition for innovation and an or truth that is so big, so obvious, that Care Centre site. absolute game changer when it comes it’s impossible to overlook – yet we We have been thinking big, wanting to to conceptualising and implementing pretend is not there because no one pre-empt and precipitate change rather successful organisational change. We wants to discuss it. than simply adapt and react to it. The would do well to remember a lesson or And I’ve been known to say that it’s opportunities are exciting, the two from our own adolescence, and easier to extract teeth out of a live challenges are enormous, the outcomes continue to learn from our adolescent crocodile than it is to convince people still unknown. -

Issue 40: Summer 2009/10

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library Issue 40, Summer 2009 This Issue From our Summer 2009/10 edition Ken Williams looks at the fi rst Pakistan tour of Australia, 45 years ago. We also pay tribute to Richie Benaud's role in cricket, as he undertakes his last Test series of ball-by-ball commentary and wish him luck in his future endeavours in the cricket media. Ross Perry presents an analysis of Australia's fi rst 16-Test winning streak from October 1999 to March 2001. A future issue of The Yorker will cover their second run of 16 Test victories. We note that part two of Trevor Ruddell's article detailing the development of the rules of Australian football has been delayed until our next issue, which is due around Easter 2010. THE EDITORS Treasures from the Collections The day Don Bradman met his match in Frank Thorn On Saturday, February 25, 1939 a large crowd gathered in the Melbourne District competition throughout the at the Adelaide Oval for the second day’s play in the fi nal 1930s, during which time he captured 266 wickets at 20.20. Sheffi eld Shield match of the season, between South Despite his impressive club record, he played only seven Australia and Victoria. The fans came more in anticipation games for Victoria, in which he captured 24 wickets at an of witnessing the setting of a world record than in support average of 26.83. Remarkably, the two matches in which of the home side, which began the game one point ahead he dismissed Bradman were his only Shield appearances, of its opponent on the Shield table. -

Vettori Not Sold on TV Replays

14 Tuesday 16th December, 2008 decision?” Vettori asked. “The premise of cricket is the away from families. batsman always gets the Former wicket-keeper benefit of the doubt and I Healy agreed that top stars think you want to still keep Vettori not sold that part of the game in. are playing a lot of cricket “It’s when you nick it onto but insisted that they are your pad and you’re given out lbw being paid rather well by or you nick it behind and you’re given Cricket Australia and they not out. Those are the one’s we want risk becoming unpopular on TV replays to get out of the game as opposed to by openly asking for hikes. the good umpiring decisions.” “Perception is better DUNEDIN, New Zealand (AP) - New Vettori’s own experience with than the truth in many Zealand cricket captain Daniel Vettori says the review system on the fourth day cases. They are playing the television replay system being used to Sunday confirmed his reservations. more games, but they are review umpires’ decisions in his team’s After having an appeal for an lbw pretty well paid,” Healy current test series against the West Indies decision against West Indies wicket- was quoted as saying by needs to be reappraised. keeper Denesh Ramdin upheld by The Daily Telegraph. Vettori said he was concerned the sys- Ian Healy umpire Amiesh Saheba, Ramdin, who “They share in the tem was not being used for the purpose for had been hit on the pad close to leg which it was intended - to eradicate incor- stumps, became the first batsman in the rect decisions - and that too many border- match to refer a decision to Koertzen line decisions were now being reviewed. -

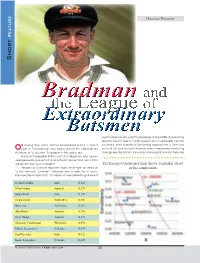

Feature Short

GANGAN PRATHAP Feature Short quality of performance (batting average) and quantity of performing opportunities (number of innings played). Sachin is probably the most N Boxing Day 2012, Kumar Sangakkara joined a select successful when quantity of performing opportunities is taken into O club of Test batsmen who had reached the extraordinary account. On quality of performance, when measured by the batting milestone of 10,000 runs. The players in this league are: average (we depart from the usual cricketing practice and here take Is Sachin the greatest in this club? Or is it Bradman, who had an average nearly double that of all in the list above? And, who of this galaxy, was the most consistent? The Exergy-Consistency map shows Tendulkar ahead Readers of Science Reporter might remember an exercise of the competition to find the most “consistent” batsmen from a select list of iconic batsmen (September 2011). “Consistency” was defined to go beyond Sachin Tendulkar India 15,645 Ricky Ponting Australia 13,378 Rahul Dravid India 13,288 Jacques Kallis South Africa 12,980 Brian Lara West Indies 11,953 Allan Border Australia 11,174 Steve Waugh Australia 10,927 Shivnarine Chanderpaul West Indies 10,696 Mahela Jayawardene Sri Lanka 10,674 Sunil Gavaskar India 10,122 Kumar Sangakkara Sri Lanka 10,045 SCIENCE REPORTER, FEBRUARY 2013 30 Short Feature This is a composite that combines quality and consistency along with quantity. If such an indicator is an acceptable measure for batting performance, then Tendulkar is once again ahead of the rest of the competition. Sachin is probably the most successful when quantity of performing opportunities is taken into account. -

PDF Download the Victory Tests : England V Australia 1945 Ebook

THE VICTORY TESTS : ENGLAND V AUSTRALIA 1945 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mark Rowe | 288 pages | 16 Sep 2010 | Sportsbooks Ltd | 9781899807949 | English | Cheltenham, United Kingdom The Victory Tests : England V Australia 1945 PDF Book Mark Rowe Author Books. Denis Compton's pull saw England home after Laker 4—75 and Lock 5—45 had bowled Australia out for in their second innings. Set to win by Norman Yarley, the visitors secured the draw, and almost won, with a valiant for 7. Cowdrey was back as England captain after Brian Close had characteristically refused to apologise after a time wasting incident in a county match at Edgbaston. England beat the South Africans 3—1 in a series notable for Len Hutton's dismissal 'obstructing the field' in his th test innings at the Oval. AV Bedser. Want more like this? England played well in their next two series, defeating South Africa 1—0 on the — tour, the last they made before South Africa's isolation. As was the case after the Great War life could not go on as it had before the conflict, as societies evolve rapidly in wartime. England claimed that Bradman had been caught by Ikin off Voce for 28 but the umpire did not agree and 'The Don' made Colin McCool. Brian Close , with a charging 70 had taken England to the brink of victory after Dexter's dashing 70 in the first innings against the fearsome pace of Hall and Charlie Griffith with Fred Trueman taking 11 for Excitement tinged with a little fear! After you're set-up, your website can earn you money while you work, play or even sleep! Peter Loader took England's first home hat trick since at Headingley. -

Comparative Analysis of Top Test Batsmen Before and After 20 Century

Joshi & Raizada (2020): Comparative analysis of top test batsmen Nov 2020 Vol. 23 Issue 17 Comparative analysis of top Test batsmen before and after 20th century Pushkar Joshi1 and Shiny Raizada2* 1Student, MBA, 2Assistant Professor,Symbiosis School of Sports Sciences, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India *Corresponding author: [email protected] (Raizada) Abstract Background:This research paper derives that which generation of top batsmen (before 20th century and after 20th century) are best when compared on certain parameters.Methods: The authorcompared both generation top batsmen on parameters such as overall average, average away from home, number of not outs and outs during that particular batsman’s career (weighted batting average). Conclusion: This research concludes that the top batsmen after 20th century have an edge over top batsmen before 20th century. Keywords: Bowling Average, Cricket, Overall Batting Average, Weighted Batting Average, Wickets How to cite this article: Joshi P, Raizada S (2020): Comparative analysis of top test batsmen before and after 20th century, Ann Trop Med & Public Health; 23(S17): SP231738. DOI: http://doi.org/10.36295/ASRO.2020.231738 1. Introduction: Cricket as a game has evolved as an intense competition after its invention in early 17th century. Truth be told, a progression of Codes of Law has administered this game for more than 250 years. Much the same as baseball (which could be called cricket's cousin in light of their likenesses), cricket's fundamental element is the technique in question and that is the primary motivation behind why cricket fans love the game to such an extent. -

Xref Cricket Catalogue for Auction

Page:1 Oct 20, 2019 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A SPORTING MEMORABILIA - General & Miscellaneous Lots 2 Eclectic group comprising 'The First Over' silk cricket picture; Wayne Carey mini football locker; 1973 Caulfield Cup glass; 'Dawn Fraser' swimming goggles; and 'Greg Norman' golf glove. (5 items) 100 3 Autographs on video cases noted Lionel Rose, Jeff Fenech, Dennis Lillee, Kevin Sheedy, Robert Harvey, Peter Hudson, Dennis Pagan & Wayne Carey. (7) 100 4 Books & Magazines 1947-56 'Sporting Life' magazines (31); cricket books (54) including 'Bradman - The Illustrated Biography' by Page [1983] & 'Coach - Darren Lehmann' [2016]; golf including 'The Sandbelt - Melbourne's Golfing Haven' limited edition 52/100 by Daley & Scaletti [2001] & 'Golfing Architecture - A Worldwide Perspective Volume 3' by Daley [2005]. Ex Ken Piesse Library. (118) 200 6 Ceramic Plates Royal Doulton 'The History of the Ashes'; Coalport 'Centenary of the Ashes'; AOF 'XXIIIrd Olympiad Los Angeles 1984'; Bendigo Pottery '500th Grand Prix Adelaide 1990'; plus Gary Ablett Sr caricature mug & cold cast bronze horse's head. (6) 150 CRICKET - General & Miscellaneous Lots 29 Collection including range of 1977 Centenary Test souvenirs; replica Ashes urn (repaired); stamps, covers, FDCs & coins; cricket mugs (3); book 'The Art of Bradman'; 1987 cricket medal from Masters Games; also pair of cups inscribed 'HM King Edward VIII, Crowned May 12th 1937' in anticipation of his cancelled Coronation. Inspection will reward. (Qty) 100 30 Balance of collection including Don Bradman signed postcard & signed FDC; cricket books (23) including '200 Seasons of Australian Cricket'; cricket magazines (c.120); plus 1960s 'Football Record's (2). (Qty) 120 Ex Lot 31 31 Autographs International Test Cricketers signed cards all-different collection mounted and identified on 8 sheets with players from England, Australia, South Africa, West Indies, India, New Zealand, Pakistan & Sri Lanka; including Alec Bedser, Rod Marsh, Alan Donald, Lance Gibbs, Kapil Dev, Martin Crowe, Intikhab Alam & Muttiah Muralitharan.