Better for Whom? Present and Prospective Camden Resident Perspectives’ on State-Mandated Renaissance Charter Schools and Recent Camden Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Camden-Waterfron

Office of the Mayor 520 Market Street Camden, New Jersey 08101 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: September 24, 2015 City of Camden: Vince Basara 856-757-7200 Liberty Contact: Jeanne Leonard 610-648-1704 CITY OF CAMDEN, BUSINESS & COMMUNITY LEADERS ANNOUNCE THAT LIBERTY PROPERTY TRUST WILL LEAD DEVELOPMENT OF “THE CAMDEN WATERFRONT Master Plan By Renowned Robert A.M. Stern Architects Will Redefine City’s Waterfront CAMDEN, NJ: Mayor Dana L. Redd, business and community leaders were today joined by Governor Christie as they announced that Liberty Property Trust will lead development of “The Camden Waterfront,” a new approximately $1 billion development that will redefine the Camden Waterfront by creating as much as 1.7 million square feet of office space and include a hotel, retail and a residential component. The development would be the largest private sector investment in Camden’s history, creating thousands of construction jobs and bringing thousands of permanent jobs to the City. Camden Mayor Dana Redd was joined at the 3:00 PM announcement at the Adventure Aquarium in Camden by New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, Bill Hankowsky, Chairman, President & Chief Executive Officer of Liberty Property Trust, renowned architect Robert A.M. Stern, and Richard T. Smith, President of the NAACP New Jersey State Conference. “’The Camden Waterfront’ represents a unique opportunity to develop a project of this scale in the center of a major metropolitan area. This visionary project will reshape the central waterfront in a way that will be truly transformative for Camden,” said Bill Hankowsky. “Through the Grow NJ program, the state of New Jersey has created an economic development program which, if approved, has the potential to be truly transformative to the city of Camden. -

Jefferson Van Drew

DECEMBER 2019 GLOBE 2019 YEAR IN REVIEW NONE OF THE ABOVE WINNER OF THE YEAR BRITTANY O’NEILL OPERATIVE OF THE YEAR DONALD TRUMP’S : NEW BEST FRIEND JEFFERSON VAN DREW 2019: YEAR IN REVIEW | 1 2019: YEAR IN REVIEW | 2 NEW JERSEY GLOBE POWER LIST 2019 That removes one typically automatic Sweeney vote from the Senate Democrats, unless the senate president can convert Mike Testa into a Sweeneycan. There were also two prominent party switchers: freshman Rep. Jeff Van Drew became a Republican, and State Sen. Dawn Addiego is now a Democrat. In the year of the unlikely voter, just 27% of New Jersey voters cast their ballots in 2019 – a number that was up 5% over 2015 thanks to the state’s new vote-by-mail law that caused the participation of many New Jerseyans who would never have voted if ballots didn’t show up at their homes. A 5% increase was significant. Off-off year elections like 2019 when State Assembly candidates head the ticket happens twice every other decade, so New Jersey won’t see another one until 2035. The race for Democratic State Chairman ended in a draw – John Currie keeps the job for eighteen months, when LeRoy Jones takes over. Legislative reapportionment, which was the entire reason for the state chairman battle, gives an edge to the anti-Murphy faction – if that’s where Jones is when the new districts are drawn. Murphy continues to struggle to win the approval of New Jersey voters, yet he appears – at least right now – to have a lock on the Democratic nomination when he seeks re-election in 2021. -

Camden Genetic Research Center Gets $14M NIH Grant

Camden city News The Honorable Dana L. Redd Office of the Mayor March 18, 2015 520 Market Street Phone: 856-757-7200 Camden, New Jersey Camden celebrates $200,000 grant to restore derelict neighborhood Standing in front of an abandoned and very heavily polluted Camden Labs building on the city's south side Monday afternoon, New Jersey officials including U.S. Sen. Bob Menendez celebrated a $200,000 federal grant for neighborhood improvement. The money comes from the Environmental Protection Agency's Brownfield Planning program, and the city will use it to focus on a clean-up strategy for dilapidated areas in the Mt. Ephraim area – already a part of the federal Choice Neighborhood program. "These are legacies of failures of the past that now have to be borne by the present," said Menendez. "Look, New Jersey has a history replete with areas like this which have been successfully reclaimed. It's just going to take a lot of effort to do it." Menendez indicated that based on the scale of the city's vision, full area revitalization could take at least five years. U.S. Rep. Donald Norcross, also on hand Monday, said that for too long, the city has been talking about change. But with the Choice neighborhood program funding, and now the EPA money, it's finally happening. "What you're seeing now is the state, the county, the city and federal all coming together because they all understand how important this is now," said Norcross. In 2012, Camden was awarded a Choice Neighborhood planning grant from the U.S. -

To See the Other 99 Members

the POWER LIST2014 POLITICKER_2014_Cover.indd 4 11/14/14 8:59:46 PM NEVER LOSING SIGHT OF THE ENDGAME FOCUSNewark New York Trenton Philadelphia Wilmington gibbonslaw.com Gibbons P.C. is headquartered at One Gateway Center, Newark, New Jersey 07102 T 973-596-4500 A_POLITICKER_2014_ads.indd 1 11/13/14 10:21:34 AM NORTHEAST CARPENTERS POLTICAL EDUCATION COMMITTEE DEDICATED TO SOCIAL JUSTICE FOR THE HARD WORKING MEN AND WOMEN OF NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK STATE AS TRADE UNIONISTS AND CITIZENS, WE ARE FOCUSED ON IMPROVING INDUSTRY STANDARDS AND EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES FOR UNION CARPENTERS AND THE SMALL AND LARGE BUSINESSES THAT EMPLOY THEM. OUR ADVOCACY IS CENTERED ON A SIMPLE AND ABIDING MOTTO: “WHEN CARPENTERS WORK, NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK WORK.” FICRST AN, RARITAN PAA II, SIT A18, ISON NJ 08837 732-417-9229 Paid for by the Northeast Regional Council of Carpenters Poltical Education Committee A_POLITICKER_2014_ads.indd 1 11/13/14 10:24:39 AM PolitickerNJ.com POWER LIST 2014 Editor’s Note elcome to PolitickerNJ’s 2014 Power List, another excursion into that raucous political universe tapped like a barrel at both ends, in the words of Ben Franklin, who would have likely shuddered at the invocation of his name in the Wcontext of this decidedly New Jersey enterprise. As always, the list does not include elected ofcials, judges or past governors. In keeping with past tradition, too, it promises to stir plenty of dismay, outrage, hurt feelings, and public tantrums at the annual League of Municipalities. We welcome it all in the spirit of more finely honing this conglomerate in progress and in the name, of course, of defending what we have wrought out of the political collisions of this most interesting year. -

A New Day for New Jersey

FOR ALUMNI & FRIENDS OF ROWAN UNIVERSITY SUMMER 2013 A new day for New Jersey 16 | Permanent presence 22 Home, shacks, home 30 | Captain of a dream 36 Brown & Gold Gridiron Homecoming Country Concert Classic Picnic & Pep Rally Saturday, September 14 Friday, October 18 Join football alumni and friends for the annual pre- A limited number of alumni tickets are available for the game picnic as the Profs take on Framingham State. first-ever Homecoming Country Concert & Pep Rally Enjoy a barbecue buffet and updates on the season. featuring Liv Devine, Joe Nichols and Uncle Kracker. 11 a.m., Football Field, near the Team House 5 p.m., Rowan Hall Green Rohrer College of Business Fall Gala Class of ’88 25th Reunion Friday, September 27 Saturday, October 19 Class of ’88 classmates are invited to celebrate their 25th Join us for a dinner honoring members of the RCB Reunion. Enjoy your day at the Homecoming festivities community with special guest speaker Jeffrey Tambor and party into the night at a reunion reception in the (Arrested Development). Watch your mailbox for info. Kopenhaver Center for Alumni Engagement. We hope you take the time 6 p.m., Eynon Ballroom to attend an alumni event 5:30 p.m., Shpeen Hall this year. As the University and our alumni population Baseball Diamond Club Rowan Alumni @ NJEA continue to grow we Golf Tournament Thursday and Friday, November 7 – 8 are always seeking alumni volunteers to get Saturday, September 28 All GSC and Rowan educators are invited to visit our involved with our Alumni Baseball alumni and fans from all generations are booth at the annual NJEA Teachers Convention at the programming. -

Bnowx & Connnry

MER-L-001007-19 07/19/2019 1:00:58 PM Pg 1 of 24 Trans ID: LCV20191258709 Bnowx & CoNnnRY, LLP ATToRNEYS AT LAW :i;o uaoooN AveNue WESTMONT, NEW JERSEY 08108 (856) 8s4-8900 FAX (8s6) 858-4967 William M. Tambussi, Esq. Certified by the Supreme Court ofNew Jersey as a Civil Trial Attomey wtambuss i@brownconnery. com Direct Dial: (856) 858-8 175 July 19,2019 VIA eCOURTS Honorable Mary C. Jacobson, A.J.S.C. Superior Court of New Jersey Mercer County Criminal Courthouse 400 S. Warren Street, 4th Floor Trenton, NJ 08650 Re: George E. Norcross, et al. v. Philip D. Murphy, et al. Docket No. MER-L-001 007-l 9 Dear Judge Jacobson: We write, on behalf of Plaintiffs, in response to Defendants' request for a telephonic case management conference. Plaintiffs do not believe that a telephonic case management conference is necessary to address the issues raised in Defendants' July 19, 2019 correspondence. The context is as follows. On July 12 and 15,2019, it was reported in the media that certain members of Governor Philip Murphy's staff were engaged in weekly telephone conferences with certain outside political advisors. The role of the outside political advisors came into focus in a July 10,2019 media report that an outside political advisor to Govemor Murphy wrote "No pain, no gain" in reference to Govemor Murphy's decision to freeze budgetary funding to Cooper Health Care. On July 15, 2019 and thereafter, it was reported that discussions about the NJEDA, one of the issues before the Court, were had in the weekly telephone calls referred to as "Inside/Outside Calls." The new reports are attached for the Court's reference. -

Hearing Unit, State House Annex, PO 068, Trenton, New Jersey

Commission Meeting of APPORTIONMENT COMMISSION "Testimony from the public on the establishment of legislative districts in New Jersey that will be in effect for the next 10 years" LOCATION: Rutgers University DATE: January 29, 2011 Camden Campus Center 9:30 a.m. Camden, New Jersey MEMBERS OF COMMISSION PRESENT: Assemblyman John S. Wisniewski, Co-Chair Assemblyman Jay Webber, Co-Chair Nilsa Cruz-Perez, Vice Chair Irene Kim Asbury, Vice Chair Senator Paul A. Sarlo Senator Kevin J. O'Toole Assemblyman Joseph Cryan George Gilmore Bill Palatucci ALSO PRESENT: Frank J. Parisi Secretary Meeting Recorded and Transcribed by The Office of Legislative Services, Public Information Office, Hearing Unit, State House Annex, PO 068, Trenton, New Jersey TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Senator Donald Norcross District 5 15 Assemblyman Gilbert L. “Whip” Wilson District 5 16 Assemblyman Angel Fuentes District 5 17 Ingrid Reed Private Citizen 19 Roberto Frugone Co-Chairman New Jersey Legislative Redistricting Coalition 27 Phillip S. Warner Sr. Communications Chairperson New Jersey Legislative Redistricting Coalition, and Southern Regional Coordinator, and Member Political Action/Civil Engagement Committee New Jersey State Conference National Association for the Advancement of Colored People 28 George B. Gore Member New Jersey Legislative Redistricting Coalition, and Chairman Political Action/Civil Engagement Committee New Jersey State Conference National Association for the Advancement of Colored People 28 José F. Sosa Former Assemblyman New Jersey General Assembly 36 George Gallenthin Private Citizen 43 TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) Page Lynn Cummings Co-Founder Neighbors Empowering Pennsauken 46 Reverend Eric Dobson President Planting Seeds of Hope 48 Ev Liebman Director Organizing and Advocacy New Jersey Citizen Action 50 Frank Argote-Freyre President Latino Action Network 54 Shawn Ludwig Representing Local 1038 Communication Workers of America 61 Timothy J. -

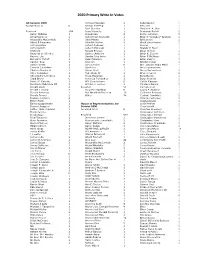

2020 Primary Write in Votes

2020 Primary Write In Votes US Senator DEM Patricia Flanagan 2 Bella Bannet 1 Accepted As Is 0 Patrick M Rettig 1 Ben Iver 1 Ravi Shankar 1 Benjamin A. Shor 1 Resolved 109 Rena Margulis 1 Benjamin Perloff 2 Aaron Widman 1 Republican 3 Bernie Sanders 3 Al Camaione sr 1 Richard Ian Reynolds 1 Bharet " Gujuboy" Graham 1 Alexandria McCormick 0 Rikin Metha 1 Bill Lennon 1 Alfred E Neumann 1 RiKinRik Mehta 4 Black Lives Matter 1 Anthony Hack 1 Robert Andrews 1 Booker 1 Anthony Ritz 1 Robert Stimelski 1 Brandy M Blout 1 Anybody 1 Ronald Reagan 1 Brian Hueber 1 Anybody but Booker 1 Samuel Anthony 1 Brian K. Everett 1 Anyone else 1 Sandra Diaz-twine 1 Brian P McShane 1 Benjamin Perloff 1 Sean Peterson 1 Brian Valerio 1 Carolyn Koel 1 Shaingh 1 Bridget Poisel 1 carson wentz 1 Simon Fisher 0 Bro. Zawdie Abdul Malik 1 Centrist Candidate 2 Sparticus 1 Bruce springsteen 1 Charles Rhodes Jr 1 Stuart Pratt 1 Bruce Springsteen 2 Chris Columbus 1 Take Back NJ 1 Bryce Hewlett 2 Christopher L Hedges 1 Tricia Flanagan 1 Bugs Bunny 1 Craig Bruno 0 Veronica Fernandez 1 Byrce Hewlett 1 Diane M. Galeoke 1 Will Cunningham 0 Caitlin Garazzo 1 Dominick Mellchiore III 1 William J. Lennon 1 Candace Owens 1 Donald Duck 2 Rejected 54 Carolyn Koel 1 Donald J Trump 2 Incorrect Spelling 0 Casey F. McAleer 1 Donald Norcross 1 Not Qualified/Declared 16 Catherine Reisman 1 Donald Trump 2 Other 38 Centrist Candidate 2 Dwayne Johnson 2 Charene Scheeper 1 Elmer Fudd 1 Charles Drass 1 Emma Guggenheim 1 House of Representatives 1st Chris Heffner 1 Eugene Anagnos 2 District DEM -

Preparedness Meets Opportunity: Women's Increased Representation in the New Jersey Legislature

Preparedness Meets Opportunity: Women's Increased Representation in the New Jersey Legislature Susan J. Carroll and Kelly Dittmar July 2012 Center for American Women and Politics Eagleton Institute of Politics 191 Ryders Lane, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 www.cawp.rutgers.edu Women's Increased Representation in the New Jersey Legislature - 1 - ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Several studies on the descriptive representation of women in office have examined questions related to candidate emergence, often trying to explain why so few women run for office (e.g., Bledsoe and Herring 1990; Fox and Lawless 2004; Fulton et al. 2006; Lawless and Fox 2010; Sanbonmatsu, Carroll, and Walsh 2009). Another body of research has focused largely on how the political opportunities available to women affect their descriptive representation among elected officials, analyzing, for example, the effects of electoral arrangements, term limits, and quota systems (e.g., Carroll and Jenkins 2001; Dahlerup 2006; Darcy, Welch, and Clark 1994; Krook 2009; Rule and Zimmerman 1994). Far less often have the "supply" side and the "demand" side of women's political representation been investigated together in the same study in order to understand how they interact. Through a case study of women's representation in the legislature of one US state, New Jersey, we show not only that supply-side and demand-side factors are both important, but also that they can work together to produce a significant increase in the numbers of women serving in office. This paper examines the factors that account for the rapid rise in the numbers of women legislators in New Jersey, focusing primarily on the time period from 2004 through 2011. -

Trump's New Jersey Collaborators

Trump’s New Jersey Collaborators The Network of Powerful Corporate Interests Profiting from a Trump Administration June 2017 NJ Communities United Introduction Donald Trump’s agenda spells disaster for America’s working families. Working class communities - particularly communities of color - will be harmed by Trump Administration policies. Public schools will continue to close as privately-run, publicly funded-charter and Renaissance schools continue expanding. More families will fall into financial crisis caused by medical debt, as healthcare costs continue to spiral out of reach for families. Funding for wrap-around services and early childhood education is likely to evaporate under the weight of massive tax cuts for the wealthy. And the same Wall Street actors who caused the global economic meltdown in 2008, will be less-regulated and handed more leeway to continue peddling toxic financial products without fear of prosecution. America’s ultra-rich elites are set to make billions in profits from the very same policies that will de-stablize and harm working class communities. Although New Jersey is one of the wealthiest states in the nation, it’s also one of the most unequal.1 New Jersey continues to lead the nation in foreclosures2. The dismantling of the public school systems in Camden and Newark - largely Black and Brown cities - stands in stark contrast to the robust public school systems in more affluent, largely white communities across New Jersey. Despite the occasional rhetoric of “resistance” from elected leaders in New Jersey’s Democratic Party, a powerful group of corporate leaders have hijacked the Democratic Agenda, while also maintaining close personal, business and political relationships with Donald Trump, his business, and his administration. -

2021 YEAR in ADVANCE 2 Message from the Editor YEAR in ADVANCE 2021

2021 YEAR IN ADVANCE 2 Message from the Editor YEAR IN ADVANCE 2021 P.O. Box 66 Verona, NJ 07044 [email protected] www.InsiderNJ.com Max Pizarro Editor-in-Chief [email protected] Republicans used to be those bankably bow-tied guys who could absorb a pink belly, and then earnestly glaze-over the eyeballs of their guilt-tripped tormentors with lectures about Nixon and Reagan. Now they wear minotaur headdresses and storm the U.S. Capitol. That’s an overload of nerdly karma gone miserably haywire, but such are the trippy times in which we live. Every year we put together a run-down on what to expect in the months ahead in New Jersey politics, and we usually manage to get it out a little earlier than February, Pete Oneglia but the ongoing issuance of real-time – sometimes nutjob – news made the future General Manager seem farther away than usual and the present all the more urgent. [email protected] Amid all the crazy political sparks, including the most unorthodox – and certainly most obnoxious – transition of power by a departing executive in U.S. presidential Michael Graham CEO history – we finally found that little crosscurrent between now and then to comment on our coming current events. John F.X. Graham Publisher Herein find assessments of the main collisions at hand, minus some of the local ones that will no doubt provide their own special parochial flavor. Ryan Graham Associate Publisher Edison comes to mind. 3 WISHING EVERYONE A HAPPY & HEALTHY NEW YEAR Executive Board Committee Dr. Patricia Campos-Medina, Immediate Past President • Zulima Farber, President Emeritus • Carol Cuadradro, Vice President • Lucia Gomez, Vice President • Arlene Quiñones Perez, Treasurer • Aida Figueroa-Epifanio Cristina Pinzon, Public Relations Secretary Laura Matos,General Board Members President Grissele Camacho • Milagros Camacho • Flora Castillo • Sonia Delgado • Lizette Delgado Rosa Farias • Kay LiCausi • Andrea Martinez- Orbe • Analilia Mejia • Carmen Mendiola Noemi Velazquez • Nohemi G. -

Camden, New Jersey and the Municipal Rehabilitation and Economic Recovery Act of 2002

THE POLITICAL FUTURE OF CITIES: CAMDEN, NEW JERSEY AND THE MUNICIPAL REHABILITATION AND ECONOMIC RECOVERY ACT OF 2002 __________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY __________________________________________________________________ By Daniel J. Dougherty May 2012 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Barbara Ferman, Advisory Chair, Department of Political Science Dr. Carolyn Adams, Department of Geography and Urban Studies Dr. Megan Mullin, Department of Political Science Dr. David Bartelt, External Member, Temple University Department of Geography and Urban Studies © Copyright 2012 by Daniel J. Dougherty All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Since the mid-20th century demographic and economic changes have left older post-industrial American cities located amidst fragmented metropolitan areas and has resulted in the loss of political power accompanied by loss of economic wealth. This has left urban centers in the Northeast and Midwest United States in various states of decline. Located within the sixth largest metropolitan area in the country, the City of Camden, New Jersey is one of America’s most distressed cities. During the longest period of decline and de-industrialization in the 1960s and 1970s, Camden lost nearly half of its industrial job base, more than other de-industrializing American cities and over one-third of its population. Currently, Camden’s circumstances related to concentrated poverty, unemployment, failing schools and a crumbling infrastructure typify the worst consequences of urban decline. The Municipal Rehabilitation and Economic Recovery Act (“Camden Recovery Act”) passed in 2002 was state-level legislation designed to intervene in Camden’s municipal operations and re-structure economic development in the city in a way not seen since the Great Depression.