The ILO Convention No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hovedplan for Skogbruksplanlegging Med MIS 2021-2030

HOVEDPLAN SKOGBRUKSPLANLEGGING MED MILJØREGISTRERINGER I TRØNDELAG 2021-2030 Landbruksavdelingen 2020 Innhold Innledning ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Mål for hovedplan for skogbruksplanlegging med miljøregistreringer 2020-2029 ................................ 2 Status skogbruksplanlegging med miljøregistreinger ............................................................................. 2 Forhold som legges til grunn i prioriteringene i hovedplanen ................................................................ 7 Handlingsplan 2020-2022 ........................................................................................................................ 9 Framdriftsplan 2023-2029 ....................................................................................................................... 9 Innledning En skogbruksplan med miljøregistreringer er det viktigste verktøyet skogeieren har for å forvalte skogressursene og miljøverdiene på sin eiendom, og er en forutsetning for at skogeieren skal utføre sin næringsvirksomhet basert på god kunnskap om ressursene og miljøverdier. Skogbruksplan med miljøregistreringer er også svært nyttig for de som veileder skogeieren i sin skogforvaltning, eller som selger tjenester til skogeieren. I tillegg det et viktig verktøy for offentlige myndigheter i arbeidet med nå målene i skogpolitikken. Fylkesmannen har en sentral rolle i skogbruksplanleggingen i fylket. Oppgaven med å -

Taxi Midt-Norge, Trøndertaxi Og Vy Buss AS Skal Kjøre Fleksibel Transport I Regionene I Trøndelag Fra August 2021

Trondheim, 08.02.2021 Taxi Midt-Norge, TrønderTaxi og Vy Buss AS skal kjøre fleksibel transport i regionene i Trøndelag fra august 2021 Den 5. februar 2021 vedtok styret i AtB at Taxi Midt-Norge, TrønderTaxi og Vy Buss AS får tildelt kontraktene for fleksibel transport i Trøndelag fra august 2021. Transporttilbudet vil være med å utfylle rutetilbudet med buss. I tillegg er det tilpasset både regionbyer og distrikt, med servicetransport i lokalmiljøet og tilbringertransport for å knytte folk til det rutegående kollektivnettet med buss eller tog. Fleksibel transport betyr at kundene selv forhåndsbestiller en tur fra A til B basert på sitt reisebehov. Det er ikke knyttet opp mot faste rutetider eller faste ruter, men innenfor bestemte soner og åpningstider. Bestillingen skjer via bestillingsløsning i app, men kan også bestilles pr telefon. Fleksibel transport blir en viktig del av det totale kollektivtilbudet fra høsten 2021. Tilbudet er delt i 11 kontrakter. • Taxi Midt-Norge har vunnet 4 kontrakter og skal tilby fleksibel transport i Leka, Nærøysund, Grong, Høylandet, Lierne, Namsskogan, Røyrvik, Snåsa, Frosta, Inderøy og Levanger, deler av Steinkjer og Verdal, Indre Fosen, Osen, Ørland og Åfjord. • TrønderTaxi har vunnet 4 kontakter og skal tilby fleksibel transport i Meråker, Selbu, Tydal, Stjørdal, Frøya, Heim, Hitra, Orkland, Rindal, Melhus, Skaun, Midtre Gauldal, Oppdal og Rennebu. • Vy Buss skal drifte fleksibel transport tilpasset by på Steinkjer og Verdal, som er en ny og brukertilpasset måte å tilby transport til innbyggerne på, og som kommer i tillegg til rutegående tilbud med buss.Vy Buss vant også kontraktene i Holtålen, Namsos og Flatanger i tillegg til to pilotprosjekter for fleksibel transport i Røros og Overhalla, der målet er å utvikle framtidens mobilitetstilbud i distriktene, og service og tilbringertransport i områdene rundt disse pilotområdene. -

ÅRSRAPPORT 05 Det Har Vært Et År Med Ekstremt Vær I Midt-Norge

ÅRSRAPPORT 05 Det har vært et år med ekstremt vær i Midt-Norge. Ekstremt uvær. Det rammet transformatorkiosken på Vikstrøm 13. februar og kraftforsyningen til Frøya og deler av Hitra lå nede i flere timer. KILE-kostnaden for det ene strømbruddet var 1,3 millioner kr. I løpet av året ble det etablert ny strømforsyning til Frøya med renovert og delvis nybygd høyspentlinje og 350 meter sjøkabel over Dolmsundet. innhold Innhold: Fakta om TrønderEnergi 5 Konsernsjefen har ordet 7 2005 Kraftfull verdiskapning 12 Virksomhetsstyring 16 TrønderEnergi, et miljøselskap 24 Våre forretningsområder 27 Forretningsområde kraft 27 ÅRSRAPPORT ÅRSRAPPORT Forretningsområde nett 32 Forretningsområde elektro 34 Årsberetning 35 Nøkkeltall 46 Resultatregnskap 47 Balanse 48 Kontantstrømoppstilling 50 Revisjonsberetning 51 Noter TrønderEnergi konsern 52 Noter TrønderEnergi AS 64 Verdiskapningsregnskap 73 side3 side 4 ÅRSRAPPORT 2005 Fakta om TrønderEnergi Fakta om TrønderEnergi TrønderEnergi er organisert som et konsern med Samlet tilsigsavhengig krafttilgang er 1831 GWh pr. år i et TrønderEnergi AS som morselskap og fire datterselskap: middelår. 2005 TrønderEnergi Kraft AS, TrønderEnergi Nett AS, TrønderElektro AS og Orkdal Fjernvarme AS (OFAS). Selskapet driver primæromsetning av energi i det Selskapets forretningskontor er i Trondheim. nordiske kraftmarkedet gjennom fysisk og finansiell krafthandel og salg til sluttbrukere i privat- og bedrifts- TrønderEnergi Kraft AS har ansvaret for kraftproduksjon markedet. Selskapet har samarbeidsavtaler om kraft- og kraftomsetning, TrønderEnergi Nett AS har ansvar for omsetning med tre distribusjonsverk. Gjennom disse energitransport, utbygging, drift og vedlikehold av avtalene omsettes ca. 270 GWh på årsbasis. regional- og distribusjonsnettet, mens TrønderElektro AS ÅRSRAPPORT driver installasjons- og butikkvirksomhet. TrønderEnergi Nett AS eier, driver og bygger et regional- nett i store deler av Sør-Trøndelag. -

Program for Folkehelsearbeid I Kommunene 2017-2027

Program for folkehelsearbeid i kommunene 2017-2027 Program for folkehelsearbeid i Trøndelag 2017-2023 Operasjonalisering av styringssirkelen Program for folkehelsearbeid i kommunene 2017-2027 ✓ Tiårig satsing for å utvikle kommunenes arbeid med å fremme befolkningens helse og livskvalitet. ✓ Satsinga skal bidra til å styrke kommunenes langsiktige og systematiske folkehelsearbeid jf. folkehelseloven. Programmet skal særlig bidra til i enda større grad å integrere psykisk helse som del av det lokale folkehelsearbeidet og fremme lokalt rusforebyggende arbeid. ✓ Barn og unge er prioritert målgruppe. ✓ Kunnskapsbasert utvikling og spredning av tiltak bl.a. for å styrke barn og unges trygghet, mestring og bruk av egne ressurser. ✓ Hindre utenforskap ved å fremme tilhørighet, deltakelse og aktivitet i lokalsamfunnet. Satsinga er tenkt befolkningsretta og ikke rettet mot risikogrupper. Program for folkehelsearbeid i kommunene 2017-2027 ✓ tilrettelegge for kunnskapsbasert utvikling av arbeidsmåter, tiltak og verktøy ✓ stimulere til samarbeid mellom kommunesektoren og forskningsmiljøer om utviklingsarbeidet. ✓ Økt samarbeid mellom kommunale aktører, bl.a. helsetjenesten, skole og barnehage, politiet og frivillig sektor i utvikling og utprøving av tiltak, men også andre. ✓ Kommunene foreslår tiltak basert på eget utfordringsbilde, målsettinger og planer. ✓ Kommunen kan se behov for å endre eller styrke noe, utvikle noe eget eller prøve ut noe som er utviklet et annet sted, som ikke tidligere har vært forskningsmessig evaluert. Det skal være et element av innovasjon i tiltaksutviklingen. ✓ Tiltak kan forstås bredt i den forstand at det også kan omhandle utprøving av organisatoriske endringer eller samhandlingstiltak internt i kommunen. Betegnelsen «program» innebærer flere parallelle og koordinerte prosesser som samlet skal bidra til å styrke det helsefremmende arbeidet i kommunene: 1. -

Lasting Legacies

Tre Lag Stevne Clarion Hotel South Saint Paul, MN August 3-6, 2016 .#56+0).')#%+'5 6*'(7674'1(1742#56 Spotlights on Norwegian-Americans who have contributed to architecture, engineering, institutions, art, science or education in the Americas A gathering of descendants and friends of the Trøndelag, Gudbrandsdal and northern Hedmark regions of Norway Program Schedule Velkommen til Stevne 2016! Welcome to the Tre Lag Stevne in South Saint Paul, Minnesota. We were last in the Twin Cities area in 2009 in this same location. In a metropolitan area of this size it is not as easy to see the results of the Norwegian immigration as in smaller towns and rural communities. But the evidence is there if you look for it. This year’s speakers will tell the story of the Norwegians who contributed to the richness of American culture through literature, art, architecture, politics, medicine and science. You may recognize a few of their names, but many are unsung heroes who quietly added strands to the fabric of America and the world. We hope to astonish you with the diversity of their talents. Our tour will take us to the first Norwegian church in America, which was moved from Muskego, Wisconsin to the grounds of Luther Seminary,. We’ll stop at Mindekirken, established in 1922 with the mission of retaining Norwegian heritage. It continues that mission today. We will also visit Norway House, the newest organization to promote Norwegian connectedness. Enjoy the program, make new friends, reconnect with old friends, and continue to learn about our shared heritage. -

Presentasjon SF Og TRFK

Planbehandling 2018 - 2020 300 266 251 252 250 239 224 209 200 150 100 51 50 44 36 33 36 27 23 16 16 17 16 17 8 9 8 6 4 4 2 1 0 1 0 1 0 Oppstartsvarsel Reguleringsplan på Planprogram på Annet Kommuneplanens Kommuneplanens Kommunedelplan Interkommunal plan Planstrategi Konsesjon høring høring arealdel samfunnsdel 2018 2019 2020 Reguleringsplaner 2018-2020 300 266 251 252 250 200 167 150 122 100 94 81 79 50 50 7 8 9 4 6 1 0 RPH Planer m/innsigelser Antall innsigelser Planer til mekling Planer til KMD 2018 2019 2020 Foto: Leka Kommuner som planlegger revidering av samfunnsdelen i Raarvihke Nams- Røyrvik perioden 2020 - 2023 Nærøysund skogan Høy- Namsos landet Flatanger Over- Grong halla Lierne Seksjon kommunal Osen Snåase Snåsa Åfjord Steinkjer Frøya Ørland Inderøy Verdal Indre Fosen Hitra Levanger Frosta Stjørdal Trondheim Malvik Meråker Heim Skaun Orkland Melhus Selbu Rindal Tydal Midtre Gauldal Skal ikke rullere KPS i perioden Rennebu Holtålen 1. Frøya 2. Malvik 3. Meråker Oppdal 4. Namsos Røros 5. Rindal 6. Selbu 7. Stjørdal 8. Tydal 4 Leka Kommuner som planlegger revidering av arealdelen i Raarvihke Nams- Røyrvik perioden 2020 - 2023 Nærøysund skogan Høy- Namsos landet Flatanger Over- Grong halla Lierne Seksjon kommunal Osen Snåase Snåsa Åfjord Steinkjer Frøya Ørland Inderøy Verdal Indre Fosen Hitra Levanger Frosta Stjørdal Trondheim Malvik Meråker Heim Skaun Orkland Melhus Selbu Kystsoneplan Namdal Rindal Leka, Nærøysund, Namsos, Flatanger, Osen, Åfjord, Ørland (Bjugn) Tydal Midtre Gauldal Rennebu Holtålen Skal ikke rullere arealdel i planperioden 1. Flatanger (utover kystsoneplan) 2. Grong Oppdal 3. -

Fact Sheet on "Overview of Norway"

Legislative Council Secretariat FSC21/13-14 FACT SHEET Overview of Norway Geography Land area Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is located in northern Europe. It has a total land area of 304 282 sq km divided into 19 counties. Oslo is the capital of the country and seat of government. Demographics Population Norway had a population of about 5.1 million at end-July 2014. The majority of the population were Norwegian (94%), followed by ethnic minority groups such as Polish, Swedish and Pakistanis. History Political ties Norway has a history closely linked to that of its immediate with neighbours, Sweden and Denmark. Norway had been an Denmark and independent kingdom in its early period, but lost its Sweden independence in 1380 when it entered into a political union with Denmark through royal intermarriage. Subsequently both Norway and Denmark formed the Kalmar Union with Sweden in 1397, with Denmark as the dominant power. Following the withdrawal of Sweden from the Union in 1523, Norway was reduced to a dependence of Denmark in 1536 under the Danish-Norwegian Realm. Union The Danish-Norwegian Realm was dissolved in between January 1814, when Denmark ceded Norway to Sweden as Norway and part of the Kiel Peace Agreement. That same year Sweden Norway – tired of forced unions – drafted and adopted its own Constitution. Norway's struggle for independence was subsequently quelled by a Swedish invasion. In the end, Norwegians were allowed to keep their new Constitution, but were forced to accept the Norway-Sweden Union under a Swedish king. Research Office page 1 Legislative Council Secretariat FSC21/13-14 History (cont'd) Independence The Sweden-Norway Union was dissolved in 1905, after the of Norway Norwegians voted overwhelmingly for independence in a national referendum. -

Nye Fylkes- Og Kommunenummer - Trøndelag Fylke Stortinget Vedtok 8

Ifølge liste Deres ref Vår ref Dato 15/782-50 30.09.2016 Nye fylkes- og kommunenummer - Trøndelag fylke Stortinget vedtok 8. juni 2016 sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke fra 1. januar 2018. Vedtaket ble fattet ved behandling av Prop. 130 LS (2015-2016) om sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag og Sør-Trøndelag fylker til Trøndelag fylke og endring i lov om forandring av rikets inddelingsnavn, jf. Innst. 360 S (2015-2016). Sammenslåing av fylker gjør det nødvendig å endre kommunenummer i det nye fylket, da de to første sifrene i et kommunenummer viser til fylke. Statistisk sentralbyrå (SSB) har foreslått nytt fylkesnummer for Trøndelag og nye kommunenummer for kommunene i Trøndelag som følge av fylkessammenslåingen. SSB ble bedt om å legge opp til en trygg og fremtidsrettet organisering av fylkesnummer og kommunenummer, samt å se hen til det pågående arbeidet med å legge til rette for om lag ti regioner. I dag ble det i statsråd fastsatt forskrift om nærmere regler ved sammenslåing av Nord- Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke. Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet fastsetter samtidig at Trøndelag fylke får fylkesnummer 50. Det er tidligere vedtatt sammenslåing av Rissa og Leksvik kommuner til Indre Fosen fra 1. januar 2018. Departementet fastsetter i tråd med forslag fra SSB at Indre Fosen får kommunenummer 5054. For de øvrige kommunene i nye Trøndelag fastslår departementet, i tråd med forslaget fra SSB, følgende nye kommunenummer: Postadresse Kontoradresse Telefon* Kommunalavdelingen Saksbehandler Postboks 8112 Dep Akersg. 59 22 24 90 90 Stein Ove Pettersen NO-0032 Oslo Org no. -

Last Ned Prosjektplanen (PDF, 715

Modellkommuneprosjekt Inkludering på alvor Prosjektplan for Indre Fosen kommune Versjon 3.0 Innhold 1 Mål og rammer ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Bakgrunn ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Definisjon ................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Menneskesyn........................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Modellkommuneprosjektet Inkludering på alvor ................................................................... 6 1.5 Effektmål ................................................................................................................................. 6 1.6 Resultatmål .............................................................................................................................. 7 1.7 Risikoanalyse ........................................................................................................................... 8 1.8 Rammer ................................................................................................................................... 8 2 Organisering .................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Prosjektledelse ....................................................................................................................... -

Development of Minor Late-Glacial Ice Domes East of Oppdal, Central Norway

NGUBull441_INNMAT 21.04.05 14:58 Side 39 BJØRN A.FOLLESTAD NGU-BULL 441, 2003 - PAGE 39 Development of minor late-glacial ice domes east of Oppdal, Central Norway BJØRN A. FOLLESTAD Follestad, B. A. 2003: Development of minor late-glacial ice domes east of Oppdal, Central Norway. Norges geologiske undersøkelse Bulletin 441, 39–49. Glacial striations and ice-marginal forms such as lateral moraines and meltwater channels show that a major north- westerly-directed ice flow invaded the Oppdal area prior to the Younger Dryas (YD) Chronozone.Through the main valley from Oppdal to Fagerhaug and Berkåk, a northerly ice flow followed the major northwesterly-directed flow and is correlated with the early YD marginal deposits in the Storås area. A marked, younger, westerly-directed ice flow from a late-glacial dome east of the Oppdal area is thought to correspond with the Hoklingen ice-marginal deposits dated to the late YD Chronozone in the Trondheimsfjord district. In the main Oppdal-Fagerhaug-Berkåk valley, this younger ice flow turned to the southwest and can be traced southwards to the Oppdal area where it joined the remnants of a glacier in the Drivdalen valley. Along the western side of the mountain Allmannberget, a prominent set of lateral, glacial meltwater channels indicates a drainage which turned westward as it met and coa- lesced with the N-S orientated glacier in Drivdalen. The mountain ridge linking Allmannberget (1342 m a.s.l.) and Sissihøa (1621 m a.s.l.) was a nunatak standing up above these two merging valley glaciers. The surface of the inland ice represented by the Knutshø moraine systems at c. -

Norway Maps.Pdf

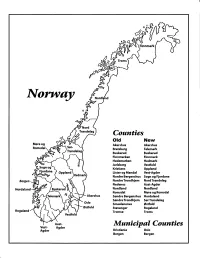

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 273 International Conference on Communicative Strategies of Information Society (CSIS 2018) Resource Policy of Russia and Norway in the Spitsbergen Archipelago: Formation of Coal Production Before World War II Sergey D. Nabok Department of International Relations St. Petersburg State University Saint Petersburg, Russia Abstract—The article is devoted to the relationship between the Agafelova. Thus, immediately after the revolution, a new coal USSR and Norway at the time of the formation of coal mining in mining company “Anglo-Russian Grumant” appeared on Svalbard before the Second World War. An analysis has been made Svalbard with a nominal capital of sixty thousand pounds of shifting the focus of attention of countries interested in the sterling [4]. It was this company that began supplying coal to archipelago from the priorities of military security to resource the Murmansk and Arkhangelsk regions, where the need for aspects. Changes in the geopolitical status of the archipelago in the solid fuel was highest. The government of New Russia has XX-XXI centuries are investigated. The article presents materials come to the conclusion that it is very expensive and unprofitable that characterize the development of relations between countries to continue to supply coal from England. According to Soviet around Svalbard. economists, it turned out that supplying Spitsbergen coal to Keywords—Russia and Norway; archipelago Spitsbergen; Kem would cost the USSR 38.85 shillings per ton, and Donetsk coal, 48.9 shillings; the delivery to Petrozavodsk is 41.54 and Svalbald; coal mining; geopolitical status; demilitarization; resources; fishery; oil and gas industry 45.95 shillings, respectively [5].