Short Story Collection by Jacqueline Curry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song and Fingerplay Book

Yankee Doodle, keep it up Yankee Doodle dandy Mind the music and the step and with the girls be handy! Father and I went down to camp Along with Captain Gooding And there we saw the men and boys As thick as hasty pudding. Chorus And there was Captain Washington And gentle folks about him They say he’s grown so tarnal proud He will not ride without them. Chorus Z is for Zoo (sung to “Wheels on the Bus”) Oh, the bear at the zoo goes Grr, grr, grr, Grr, grr, grr. Oh, the bear at the zoo goes Grr, grr, grr, All day long. Repeat additional verses: Monkey at the zoo… ooo, ooo, ooo Snake at the zoo…. hiss, hiss, hiss Lion at the zoo….raar, raar, raar …etc. Z is for Zoom Zoom, zoom zoom, We’re going to the moon. Zoom, zoom, zoom, We’ll be there very soon. So if you’d like to take a trip Just step inside my rocket ship. Zoom, zoom, zoom, We’re going to the moon. Zoom, zoom, zoom, We’ll be there very soon. 10 – 9 – 8 -7 – 6 – 5 – 4 – 3 – 2 – 1 – BLAST OFF! 40 A Counting We Will Go A counting we will go A counting we will go 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 A counting we will go. We’re counting as we clap (clap) We’re counting as we jump (jump) We’re counting as we march (march) We’re counting as we spin (turn around) Acka Backa Acka backa soda cracker, Acka backa boo. -

Lifelines 2004 a Dartmouth Medical School Literary Journal

Lifelines 2004 A Dartmouth Medical School Literary Journal Major support for this issue comes from: The Fannie and Alan Leslie Center for the Humanities at Dartmouth College and The Allen and Joan Bildner Endowment for Human and Inter-group Relations Sai Li Editor-in-Chief Meghan McCoy Allison Giordano Editor, Artwork and Photography Khalil Ayvar Undergraduate Liaisons Christy Paiva Andy Nordhoff Lori Alvord, MD Assistant Editors Stefan Balan, MD Donna DiFillippo Hiliary Plioplys Sue Ann Hennessy Copy Editor Donald Kollisch, MD Rodwell Mabaera Rodwell Mabaera Meghan McCoy Meghan McCoy Andy Nordhoff Design and Layout Joseph O’Donnell, MD Shawn O’Leary Lisanne Palomar Christy Paiva Publicity Director Hiliary Pliophys Parker Towle, MD Shawn O’Leary Editorial Board, Poetry and Prose Donna DiFillippo Administrative Advisors Joseph Dwaihy Sara Dykstra Lori Alvord, MD Kristin Elias Joseph O’Donnell, MD Rodwell Mabaera Faculty Advisors Editorial Board, Artwork and Photography Copyright ©2004 Trustees of Dartmouth College. All rights reserved. Cover Art “Contemplation Before Surgery” Joe Wilder, M.D. October 5, 1920 – July 1, 2003 Joseph Richard Wilder was born in Baltimore on October 5, 1920. He attended Dartmouth College, University of Pennsylvania, and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Joseph Wilder, athlete, surgeon, and artist, rose to the top of three professions. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame for Lacrosse in 1987 and received the Markel Award for cardio-vascular research in 1954. His paintings were exhibited at galleries and museums all over the world, including The Museum of Modern Art in New York and The National Portrait Gallery in Washington. -

Baila

1. A song shot in one of these locations is an item number featuring women dressed in traditional North Indian clothing, despite being from South India. That song would later be remade for the movie Maximum, although it’s location was changed from one of these locations. That song shot in one of these locations repeatedly lists the name of cities, and was part of a breakout film for Allu Arjun. In addition to (*) Aa Ante Amalapuram, another song shot in one of these locations features a lyric that praises someone’s speech to be “as fine as the Urdu language.” Shahrukh Khan dances on top of, for 10 points, what location in Chaiyya Chaiyya? ANSWER: Train [accept railroad or railway or equivalents] <Bollywood> 2. This word is the name of a popular dance in Sri Lanka, and a song titled “[this word] Remix Karala” was remixed into the 2011 Sri Lankan Cricket Team’s song. Another song with this word in its title claims that this word “esta cumbia,” and is by Selena. A song with another conjugation of this word in its title says (*) “Nothing can stop us tonight” before the title phrase. That song featuring this word in its title also says “Te quiero, amor mio” before the title word is repeated in the chorus. For 10 points, name this word which titles an Enrique Iglesias song, in which it precedes and succeeds the phrase “Let the rhythm take you over.” ANSWER: baila [accept bailar or bailamos - meta tossup lul] <Latin American Music> 3. The second episode of the History Channel TV show UnXplained is partially set in this location. -

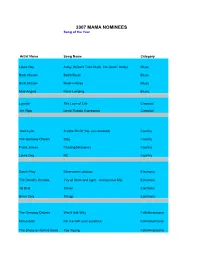

2007 Nominees

2007 MAMA NOMINEES Song of the Year Artist Name Song Name Category Laura Day Antsy (It Don't Take Much, I'm Gettin' Antsy) Blues Barb Cheron Boo's Blues Blues Barb Cheron Rockin Horse Blues Mud Angels River Landing Blues Lynette The Love of Life Classical Jim Ripp Lento Rubato Espressivo Classical Jessi Lynn A Little Bit Of You (un-released) Country The Getaway Drivers Stay Country Frank James Chasing Memories Country Laura Day RC Country Sarah Pray Bittersweet Letdown Electronic The Dorothy Heralds City of Stars and Light - Anonymous Mix Electronic Jai Bird Shiver Electronic Brian Daly Things Electronic The Getaway Drivers Won't Ask Why Folk/Americana flameshark Kill me with your sunshine Folk/Americana The Sharp & Harkins Band Too Young Folk/Americana Laura Day Singing At The Moon Folk/Americana Barb Cheron C Me Jazz Barb Cheron Boo's Blues Jazz Barb Cheron Bistro Jazz The Stellanovas Ain't Nobody Here But Us Chickens Jazz Mike Droho Chandelier Pop The New Kentucky Quarter Carry It Around Pop Lucas Cates We May Fall Pop The Getaway Drivers Oh Trudy Pop Know Boundaries the sling blade RnB/HipHop Horton the Irrelevant & August the Creep What I Know RnB/HipHop Felicia Alima I'm Down RnB/HipHop Felicia Alima Know Me RnB/HipHop Sunshine for the Blind See the River Rise Rock The New Kentucky Quarter Carry It Around Rock Oxford Monte-Ray Rock Sunshine for the Blind No More Suffering Rock subvocal I Fall Down Unique The Stellanovas Think About Your Troubles Unique The Sharp & Harkins Band Ocean View Unique Jack Sayre Thing Unique Keygal What -

Sammy Strain Story, Part 4: Little Anthony & the Imperials

The Sammy Strain Story Part 4 Little Anthony & the Imperials by Charlie Horner with contributions from Pamela Horner Sammy Strain’s remarkable lifework in music spanned almost 49 years. What started out as street corner singing with some friends in Brooklyn turned into a lifelong career as a professional entertainer. Now retired, Sammy recently reflected on his life accomplishments. “I’ve been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame twice (2005 with the O’Jays and 2009 with Little (Photo from the Classic Urban Harmony Archives) Anthony & the Imperials), the Vocal Group Hall of Fame (with both groups), the Pioneer R&B Hall of Fame (with Little An- today. The next day we went back to Ernie Martinelli and said thony & the Imperials) and the NAACP Hall of Fame (with the we were back together. Our first gig was to be a week-long O’Jays). Not a day goes by when I don’t hear one of the songs engagement at the Town Hill Supper Club, a place that I had I recorded on the radio. I’ve been very, very, very blessed.” once played with the Fantastics. We had two weeks before we Over the past year, we’ve documented Sammy opened. From the time we did that show at Town Hill, the Strain’s career with a series of articles on the Chips (Echoes of group never stopped working. “ the Past #101), the Fantastics (Echoes of the Past #102) and The Town Hall Supper Club was a well known venue the Imperials without Little Anthony (Echoes of the Past at Bedford Avenue and the Eastern Parkway in the Crown #103). -

Tributaries 2013

1 2 TRIBUTARIES Tributaries 2012-2013 Staff Editors-in-Chief: Ian Holt and Deidra Purvis Fiction Editor: Chase Eversole Nonfiction Editor: Emily O’Brien Poetry Editor: Andrew Davis Art & Design Editor: Kaylyn Flora Copy Editor: Chase Eversole Faculty Advisors: Beth Slattery and Tanya Perkins 3 Our Mission Ridicule is the tribute paid to the genius by the mediocrities. ––Oscar Wilde Tributaries is a student-produced literary and arts journal published at Indiana University East that seeks to publish invigorating and multifaceted fiction, nonfiction, poetry, essays, and art. Our modus operandi is to do two things: Showcase the talents of writers and artists whose work feeds into a universal body of creative genius while also paying tribute to the greats who have inspired us. We accept submissions on a rolling basis and publish on an annual schedule. Each edition is edited during the fall and winter months, which culminates with an awards ceremony and release party in the spring. Awards are given to the best pieces submitted in all categories. Tributaries is edited by undergraduate students at Indiana University East. 4 TRIBUTARIES Table of Contents Art “Arty art” Danielle Standley Covers “See The Love Pt. 1” Jami Dingess 7 “Never Knew Love ‘Til Now” Jami Dingess 49 “See The Love Pt. 2” Jami Dingess 75 “Monsters in Paradise” Jami Dingess 100 Fiction “The Right Hand Pocket” Ryland McIntyre 9 “Book ‘Em” Krisann Johnson 12 “Nude” Brittany Hudson 14 “The Enemy Within” Lynn Loring 19 “Vance Grafton” Heather Barnes 20 “Part One: The Sock Bandits” -

Spanglish Code-Switching in Latin Pop Music: Functions of English and Audience Reception

Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 II Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 © Magdalena Jade Monteagudo 2020 Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception Magdalena Jade Monteagudo http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract The concept of code-switching (the use of two languages in the same unit of discourse) has been studied in the context of music for a variety of language pairings. The majority of these studies have focused on the interaction between a local language and a non-local language. In this project, I propose an analysis of the mixture of two world languages (Spanish and English), which can be categorised as both local and non-local. I do this through the analysis of the enormously successful reggaeton genre, which is characterised by its use of Spanglish. I used two data types to inform my research: a corpus of code-switching instances in top 20 reggaeton songs, and a questionnaire on attitudes towards Spanglish in general and in music. I collected 200 answers to the questionnaire – half from American English-speakers, and the other half from Spanish-speaking Hispanics of various nationalities. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Wks on 100/40 13/10 13/11 14/10 23/11 17/14

American Top 40 SHOW# 802- ~ STAT LIST CHART DATE S /;o//?O Wks on Top Top Hot 100/40 Rank SONGTITLE Artist #ls 10s 40s 100s 13/10 1- ( 4w) CALL ME------------------ Blondie 79 2* 2 4 5 13/11 2-2 RIDE LIKE THE WIND------- Christopher Cross 80 0 1 1 1 14/10 3-3 LOST IN LOVE------------- Air Supply 80 O· 1 1 1 Billy Preston & Syreeta 69/79 2/0 15/1 6/1 13/1 - 23/11 4-4 WITH YOU I'M BORN AGAIN -- 17/14 5-5 ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL- Pink Floyd 73 l* l 2 2 12/11 6-6 FIRE LAKE---------------- Bob Seger 68 . 0 3 9 17 9/8 7-7 YOU MAY BE RIGHT--------- Billy Joel 74 0 3 10 12 13/9 8-9 SEXY EYES---------------- Dr. Hook 72 0 6 8 15 7/5 9- 11 bON'T FALL IN LOVE WITH A DREAMER-K.Rogers/K.Carnes 76/78 0/0 15/1 7/2 9/3 11/8 10-10 HOLD ON TO MY LOVE------- Jimmy Ruffin 66 0 2 4 8 6/4 11-14 BIGGEST PART OF ME------- Ambrosia 75 0 1 4 5 Archive 237th Heart Of Glass----------- Blondie (April 1979) 5/4 12-· l 5 HURT SO BAD------------- Linda Ronstadt 67 1 7 15 23 12/8 . 13-13 PILOT OF THE AIRWAVES---- Charlie Dore 80 0 0 1 l 7/4 14-17 I CAN'T HELP IT---------- Andy Gibb &ONJ 77/71 3/3 6/9 7/17 7/2 1 13/7 15-18 CARS--------------------- Gary Numan 80 0 0 1 l 12/11 16-8 I CAN'T TELL YOU WHY----- The Eagles 72 5 10 15 18 7/4 17-19 BREAKDOWN DEAD AHEAD----- Boz Scaggs 71 0 l 4 10 9/5 18-21 STOMP-------------------- The Brothers Johnson 76 0 2 4 4 7/4 19-24 FUNKYTOWN ---------------- Lipps, Inc. -

THOMAS MARVEL Director of Photography 2821 3Rd Street Santa Monica, CA 90405

THOMAS MARVEL Director of Photography 2821 3rd Street Santa Monica, CA 90405 1986- Hamilton College, Clinton NY, Bachelor of Arts 1987- Grotowski Studio Theatre, Wroclaw, Poland 1987-1989 Production Assistant 1989-1994 Studio Lighting Technician 1994-1998 Chief Lighting Technician 1998- Present, Director of Photography 2015 NARRATIVE “The Nice Guys” Camera Operator, Directed by Shane Black, DP Philippe Rousselot COMMERCIALS Harbin Beer, “Shaq and Friends” directed by Gil Green MUSIC VIDEOS Mary J. Blige “Doubt” directed by Ethan Lader 2014 COMMERCIALS Sandals Foundation, “Soles of Youth” directed by Gil Green Mexico CPTM Tourismo, “Vivirlo para Creerlo” directed by Michael Abt Diners Club, “Club Miles” directed by Alejandro Dube Novo Nordisk, “Rev Run Diabetes Awareness” directed by Ron Jacobs Novo Nordisk , “Debbie Allen Diabetes Awareness” directed by Ron Jacobs Domino’s Pizza, “Must Try” directed by Francisco Pugliese MUSIC VIDEOS Wisin ft. Pitbull, “Control” directed by Carlos Perez Ricardo Arjona, “Apnea” directed by Carlos Perez 2013 NARRATIVE “The Veil” feature film directed by Brent Ryan Green COMMERCIALS Park Hyatt, “Anthem” directed by Josh Hayward Nissan, “Skylar Gray” directed by Declan Whitbeloom 1 Pepsi, “Wally Lopez” directed by Gil Green Sanofi Pasteur, “Dana Torres PSA” directed by Ron Jacobs YouTube, “Comedy Week Promo with Arnold Schwarzenneger” directed by Nick Ryan Tigo, “Verdades” directed by Roberto Mancia Valspar Paint, “Tori and Dean” directed by Natalie Barandes WalMart, “Gain” directed by Francisco Pugliese -

United States District Court Eastern District Of

Case 2:13-cv-05463-KDE-SS Document 1 Filed 08/16/13 Page 1 of 118 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA PAUL BATISTE D/B/A * CIVIL ACTION NO. ARTANG PUBLISHING LLC * * SECTION: “ ” Plaintiff, * * JUDGE VERSUS * * MAGISTRATE FAHEEM RASHEED NAJM, P/K/A T-PAIN, KHALED * BIN ABDUL KHALED, P/K/A DJ KHALED, WILLIAM * ROBERTS II, P/K/A RICK ROSS, ANTOINE * MCCOLISTER P/K/A ACE HOOD, 4 BLUNTS LIT AT * ONCE PUBLISHING, ATLANTIC RECORDING * CORPORATION, BYEFALL MUSIC LLC, BYEFALL * PRODUCTIONS, INC., CAPITOL RECORDS LLC, * CASH MONEY RECORDS, INC., EMI APRIL MUSIC, * INC., EMI BLACKWOOD MUSIC, INC., * FIRST-N-GOLD PUBLISHING, INC., FUELED BY * RAMEN, LLC, NAPPY BOY, LLC, NAPPY BOY * ENTERPRISES, LLC, NAPPY BOY PRODUCTIONS, * LLC, NAPPY BOY PUBLISHING, LLC, NASTY BEAT * MAKERS PRODUCTIONS, INC., PHASE ONE * NETWORK, INC., PITBULL’S LEGACY * PUBLISHING, RCA RECORDS, RCA/JIVE LABEL * GROUP, SONGS OF UNIVERSAL, INC., SONY * MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT DIGITAL LLC, * SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING, LLC, SONY/ATV * SONGS, LLC, SONY/ATV TUNES, LLC, THE ISLAND * DEF JAM MUSIC GROUP, TRAC-N-FIELD * ENTERTAINMENT, LLC, UMG RECORDINGS, INC., * UNIVERSAL MUSIC – MGB SONGS, UNIVERSAL * MUSIC – Z TUNES LLC, UNIVERSAL MUSIC * CORPORATION, UNIVERSAL MUSIC PUBLISHING, * INC., UNIVERSAL-POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL * PUBLISHING, INC., WARNER-TAMERLANE * PUBLISHING CORP., WB MUSIC CORP., and * ZOMBA RECORDING LLC * * Defendants. * ****************************************************************************** Case 2:13-cv-05463-KDE-SS Document 1 Filed 08/16/13 Page 2 of 118 COMPLAINT Plaintiff Paul Batiste, doing business as Artang Publishing, LLC, by and through his attorneys Koeppel Traylor LLC, alleges and complains as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. This is an action for copyright infringement.