Brudenell White (II)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The AWA Microphone for Harbour Bridge 75Th

..The Microphone used for the Sydney Harbour Bridge Opening ceremony. Compiled by David Burger, March 2007 with material from: - Phil Burgess Telstra, - Ted Miles – ex AWA technician. Press Release No. 94 (14/03/07) – Telstra's Sydney Harbour Bridge 75th birthday gift Phil Burgess, GMD, Public Policy and Communication, Telstra. Telstra has donated a rare microphone from its historical collection used to open the Sydney Harbour Bridge 75 years ago to the Sydney Powerhouse Museum - and it has created a bit of excitement. The Reisz microphone is a rare example of Australian technology manufactured in 1930 and was used to broadcast the 1932 opening ceremony of the Sydney Harbour Bridge to thousands of people. What has made the microphone especially significant is the signatures of all 10 dignitaries at the opening ceremony, including the NSW Premier John T Lang, NSW Governor Philip Game and the Bridge's Chief Engineer, JJC Bradfield. Speaking at the official donation event, Telstra's Group Managing Director PP&C Phil Burgess said that Telstra was proud to share this wonderful piece of Australian history with the community on the 75th birthday of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. "Every good piece of history has a story behind it and this microphone is no exception," Dr Burgess said. "Thanks to the Powerhouse Museum, many more people will be able to see and understand the role it played in unveiling a great Aussie icon." Why did Telstra have the microphone in its historical collection? The microphone became one of a collection of microphones owned by Mr Philip Geeves who was announcing for AWA (Amalgamated Wireless Australia Ltd) on the day of the Sydney Harbour Bridge opening. -

RUSI of NSW Article

Jump TO Article The article on the pages below is reprinted by permission from United Service (the journal of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales), which seeks to inform the defence and security debate in Australia and to bring an Australian perspective to that debate internationally. The Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales (RUSI NSW) has been promoting informed debate on defence and security issues since 1888. To receive quarterly copies of United Service and to obtain other significant benefits of RUSI NSW membership, please see our online Membership page: www.rusinsw.org.au/Membership Jump TO Article USI Vol61 No2 Jun10:USI Vol55 No4/2005 21/05/10 1:31 PM Page 24 CONTRIBUTED ESSAY Conflict in command during the Kokoda campaign of 1942: did General Blamey deserve the blame? Rowan Tracey General Sir Thomas Blamey was commander-in-chief of the Australian Military Forces during World War II. Tough and decisive, he did not resile from sacking ineffective senior commanders when the situation demanded. He has been widely criticised by more recent historians for his role in the sackings of Lieutenant-General S. F. Rowell, Major-General A. S. Allen and Brigadier A. W. Potts during the Kokoda Campaign of 1942. Rowan Tracey examines each sacking and concludes that Blameyʼs actions in each case were justified. On 16 September 1950, a small crowd assembled in High Command in Australia in 1942 the sunroom of the west wing of the Repatriation In September 1938, Blamey was appointed General Hospital at Heidelberg in Melbourne. The chairman of the Commonwealth’s Manpower group consisted of official military representatives, Committee and controller-general of recruiting on the wartime associates and personal guests of the central recommendation of Frederick Shedden, secretary of figure, who was wheelchair bound – Thomas Albert the Department of Defence, and with the assent of Blamey. -

General Sir William Birdwood and the AIF,L914-1918

A study in the limitations of command: General Sir William Birdwood and the A.I.F.,l914-1918 Prepared and submitted by JOHN DERMOT MILLAR for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales 31 January 1993 I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of advanced learning, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. John Dermot Millar 31 January 1993 ABSTRACT Military command is the single most important factor in the conduct of warfare. To understand war and military success and failure, historians need to explore command structures and the relationships between commanders. In World War I, a new level of higher command had emerged: the corps commander. Between 1914 and 1918, the role of corps commanders and the demands placed upon them constantly changed as experience brought illumination and insight. Yet the men who occupied these positions were sometimes unable to cope with the changing circumstances and the many significant limitations which were imposed upon them. Of the World War I corps commanders, William Bird wood was one of the longest serving. From the time of his appointment in December 1914 until May 1918, Bird wood acquired an experience of corps command which was perhaps more diverse than his contemporaries during this time. -

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD [1882 – 1976] Major General Cannan is distinguished by his service in the Militia, as a senior officer in World War 1 and as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General in World War 2. Major General James Harold Cannan, CB, CMG, DSO, VD (29 August 1882 – 23 May 1976) was a Queenslander by birth and a long-term member of the United Service Club. He rose to brigadier general in the Great War and served as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General during the Second World War after which it was said that his contribution to the defence of Australia was immense; his responsibility for supply, transport and works, a giant-sized burden; his acknowledgement—nil. We thank the History Interest Group and other volunteers who have researched and prepared these Notes. The series will be progressively expanded and developed. They are intended as casual reading for the benefit of Members, who are encouraged to advise of any inaccuracies in the material. Please do not reproduce them or distribute them outside of the Club membership. File: HIG/Biographies/Cannan Page 1 Cannan was appointed Commanding Officer of the 15th Battalion in 1914 and landed with it at ANZAC Cove on the evening of 25 April 1915. The 15th Infantry Battalion later defended Quinn's Post, one of the most exposed parts of the Anzac perimeter, with Cannan as post commander. On the Western Front, Cannan was CO of 15th Battalion at the Battle of Pozières and Battle of Mouquet Farm. He later commanded 11th Brigade at the Battle of Messines and the Battle of Broodseinde in 1917, and the Battle of Hamel and during the Hundred Days Offensive in 1918. -

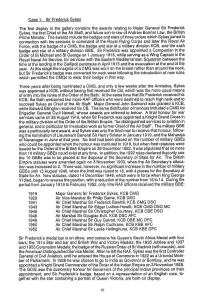

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes the First Display in the Gallery Contains

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes The first display in the gallery contains the awards relating to Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, the first Chief of the Air Staff, and future son-in-law of Andrew Bonnar Law, the British Prime Minister. The awards include the badges and stars of three orders which Sykes joined in connection with his services in command of the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force, with the badge of a CMG, the badge and star of a military division KCB, and the sash badge and star of a military division GBE. Sir Frederick was appointed a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1916, while serving as a Wing Captain in the Royal Naval Air Service, for services with the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron between the time of the landing in the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915 and the evacuation at the end of the year. At this stage the insignia of a CMG was worn on the breast rather than around the neck, but Sir Frederick’s badge was converted for neck wear following the introduction of new rules which permitted the CMGs to wear their badge in that way. Three years after being nominated a CMG, and only a few weeks after the Armistice, Sykes was appointed a KCB, without having first received the CB, which was the more usual means of entry into the ranks of the Order of the Bath. At the same time that Sir Frederick received his KCB, the Bath welcomed two more RAF officers who were destined to reach high rank and to succeed Sykes as Chief of the Air Staff: Major General John Salmond was granted a KCB, while Edward Ellington received his CB. -

“Come on Lads”

“COME ON LADS” ON “COME “COME ON LADS” Old Wesley Collegians and the Gallipoli Campaign Philip J Powell Philip J Powell FOREWORD Congratulations, Philip Powell, for producing this short history. It brings to life the experiences of many Old Boys who died at Gallipoli and some who survived, only to be fatally wounded in the trenches or no-man’s land of the western front. Wesley annually honoured these names, even after the Second World War was over. The silence in Adamson Hall as name after name was read aloud, almost like a slow drum beat, is still in the mind, some seventy or more years later. The messages written by these young men, or about them, are evocative. Even the more humdrum and everyday letters capture, above the noise and tension, the courage. It is as if the soldiers, though dead, are alive. Geoffrey Blainey AC (OW1947) Front cover image: Anzac Cove - 1915 Australian War Memorial P10505.001 First published March 2015. This electronic edition updated February 2017. Copyright by Philip J Powell and Wesley College © ISBN: 978-0-646-93777-9 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................. 2 Map of Gallipoli battlefields ........................................................ 4 The Real Anzacs .......................................................................... 5 Chapter 1. The Landing ............................................................... 6 Chapter 2. Helles and the Second Battle of Krithia ..................... 14 Chapter 3. Stalemate #1 .............................................................. -

03 Chapters 4-7 Burns

76 CHAPTER 4 THE REALITY BEHIND THE BRISBANE LINE ALLEGATIONS Curtin lacked expertise in defence matters. He did not understand the duties or responsibilities of military commanders and never attended Chiefs of Staff meetings, choosing to rely chiefly on the Governments public service advisers. Thus Shedden established himself as Curtins chief defence adviser. Under Curtin his influence was far greater than 1 it had ever been in Menzies day. Curtins lack of understanding of the role of military commanders, shared by Forde, created misunderstandings and brought about refusal to give political direction. These factors contributed to events that underlay the Brisbane Line controversy. Necessarily, Curtin had as his main purpose the fighting and the winning of the war. Some Labor politicians however saw no reason why the conduct of the war should prevent Labor introducing social reforms. Many, because of their anti-conscriptionist beliefs, were unsympathetic 2 to military needs. Conversely, the Army Staff Corps were mistrustful of their new masters. The most influential of their critics was Eddie Ward, the new Minister for Labour and National Service. His hatred of Menzies, distrust of the conservative parties, and suspicion of the military impelled him towards endangering national security during the course of the Brisbane Line controversy. But this lay in the future in the early days of the Curtin Government. Not a great deal changed immediately under Curtin. A report to Forde by Mackay on 27 October indicated that appreciations and planning for local defence in Queensland and New South Wales were based on the assumption that the vital area of Newcastle-Sydney-Port Kembla had priority in defence. -

04 Chapters 8-Bibliography Burns

159 CHAPTER 8 THE BRISBANE LINE CONTROVERSY Near the end of March 1943 nineteen members of the UAP demanded Billy Hughes call a party meeting. Hughes had maintained his hold over the party membership by the expedient of refusing to call members 1a together. For months he had then been able to avoid any leadership challenge. Hughes at last conceded to party pressure, and on 25 March, faced a leadership spill, which he believed was inspired by Menzies. 16 He retained the leadership by twenty-four votes to fifteen. The failure to elect a younger and more aggressive leader - Menzies - resulted in early April in the formation by the dissenters of the National Service Group, which was a splinter organisation, not a separate party. Menzies, and Senators Leckie and Spicer from Victoria, Cameron, Duncan, Price, Shcey and Senators McLeary, McBride, the McLachlans, Uphill and Wilson from South Australia, Beck and Senator Sampson from Tasmania, Harrison from New South Wales and Senator Collett from Western Australia comprised the group. Spender stood aloof. 1 This disturbed Ward. As a potential leader of the UAP Menzies was likely to be more of an electoral threat to the ALP, than Hughes, well past his prime, and in the eyes of the public a spent political force. Still, he was content to wait for the appropriate moment to discredit his old foe, confident he had the ammunition in his Brisbane Line claims. The Brisbane Line Controversy Ward managed to verify that a plan existed which had intended to abandon all of Australia north of a line north of Brisbane and following a diagonal course to a point north of Adelaide to be abandoned to the enemy, - the Maryborough Plan. -

Sir John Northcott

30 Sir John Northcott (1 August 1946 – 31 July 1957) Chris Cunneen The 30th representative of the Crown in New South Wales, John North- cott, was the first Australian to be State or colonial Governor.1 It was only after extraordinary pressure from the Premier William McKell that King George VI, advised by the British Government, agreed to the selection. Birth and military career John Northcott was born on 24 March 1890 at Creswick, Victoria, eldest son of English-born parents: his father, also named John, owned a general store in the nearby town of Dean, his mother was Elizabeth, née Reynolds. Young John was the eldest of four sons and one daughter. Educated at Dean State School and Grenville College, Ballarat, he was a keen member of the school cadets. He was also an enthusiastic horse rider, so in 1908 he enlisted in the Ninth Light Horse Regiment, a militia unit. Deciding on a full time career in the Army he passed the entry examinations and in 1912 joined the Permanent Military Forces as a Lieu- tenant on the Administrative and Instructional Staff. He was posted to Tasmania. On the outbreak of World War I he transferred to the Aust- ralian Imperial Force and in August 1914 was appointed Adjutant of the 12th Battalion, based at Anglesea Barracks, Hobart.2 Northcott’s service record at this time described the 24 year old as five feet eight and a half inches tall, with a fair complexion and blue eyes. His Battalion left for Egypt in October 1914. On Sunday, 25 April 1915, Northcott was one of the first to land at Anzac Cove, Gallipoli. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

Your Presentation Is the Keynote Presentation for the Block

1984 RUSI VIC BLAMEY ORATION By Major General Ken G. Cooke, ED There must be something special about a man who on the centenary of his birth and thirty-three years after his death can still trigger a gathering of so many people, including so many busy and distinguished people, in a Melbourne park on a Tuesday morning in January. So let us take a few minutes to review briefly the life of Thomas Alfred Blamey to try and determine just how this can be. He was born on 24th January, 1884 on the outskirts of Wagga Wagga, the seventh of the ten children of Richard and Margaret Blamey. His father had tried his luck at farming, both in Queensland and New South Wales, but as was often the case the ventures ended in disaster due to the old traditional enemies of drought, bush fire and fluctuating cattle prices. He then settled in Wagga where he earned his living as a contract drover. His was a pioneer family so typical of the time and it exemplified the strength of our immigrant stock both before and since. Young Tom was educated in Wagga, first at the Government school and then for the last two years at the Grammar school to which he won a place on his pure ability. His upbringing generally was as you would expect. He had to help around the family property before and after school and on vacations he worked as a tar- boy in the local shearing sheds. As he grew older he went on several droving trips to help his father. -

Chapter Xi1 Australia Doubles the A.I.F

CHAPTER XI1 AUSTRALIA DOUBLES THE A.I.F. THEAustralians and New Zealanders who returned from Gallipoli to Egypt were a different force from the adven- turous body that had left Egypt eight months before. They were a military force with strongly established, definite traditions. Not for anything, if he could avoid it, would an Australian now change his loose, faded tu& or battered hat for the smartest cloth or headgear of any other army. Men clung to their Australian uniforms till they were tattered to the limit of decency. Each of the regimental numbers which eight months before had been merely numbers, now carried a poignant meaning for every man serving with the A.I.F., and to some extent even for the nation far away in Australia. The ist, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Infantry Battalions-they had rushed Lone Pine; the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th had made that swift advance at Helles; the gth, ioth, I ith, 12th had stormed the Anzac heights; the igth, iqth, igth, 16th had first held Quinn’s, Courtney’s and Pope’s; the battalion numbers of the 2nd Division were becoming equally famous-and so with the light horse, artillery, engineers, field ambulances, transport companies, and casualty clearing stations. Service on the Gallipoli beaches had given a fighting record even to British, Egyptian and Maltese labour units that normally would have served far behind the front. The troops from Gallipoli were urgently desired by Kitchener for the defence of Egypt against the Turkish expedition that threatened to descend on it as soon as the Allies’ evacuation had released the Turkish army ANZAC TO AMIENS [Dec.