Soul-Making Dynamics: the Synthesis, Evolution, and Destiny of the Human Soul a Missing Dimension in Integral Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 FALL/WINTER SEASON the Apollo Theater Launches

2015 FALL/WINTER SEASON The Apollo Theater launches Apollo Comedy Club The new series marks the extension of the Theater’s late night programming and will kick-off with the Apollo Walk of Fame Induction of comedic legends Redd Foxx, Jackie “Moms” Mabley and Richard Pryor Other 2015 Season Highlights Include: The return of the global hip-hop dance theater festival Breakin’ Convention Just added celebrated French dance duo Les Twins Also featuring a new work developed at the Apollo by acclaimed choreographer Rennie Harris Irvin Mayfield, Dee Dee Bridgewater & the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra For the New York Concert Premiere of Bridgewater and Mayfield’s New Album ‘Dee Dee’s Feathers’ A Festive Halloween Weekend Celebration To Include A New Orleans Masquerade Themed Concert and After Party World premiere of renowned Brazilian choreographer Fernando Melo’s latest work; A co-commission with Ballet Hispanico Apollo and Jazz à Vienne’s artistic and cultural exchange continues with Je Suis Soul: A Salute To French And African Jazz And Soul A Celebration for the 35th Anniversary of the Jazz à Vienne Festival featuring French soul’s leading artists The Legendary Manu Dibango, Ben l’Oncle Soul with the Monophonics and Les Nubians The Classical Theatre of Harlem presents The First Noel: A World Premiere Musical; Book, music and lyrics by Lelund Durond Thompson and Jason Michael Webb (Harlem, NY –September 21, 2015)—On the heels of the recently announced expansion of its daytime programming with the Billie Holiday hologram show, the Apollo Theater today announced another exciting new addition to its 2015 Fall/Winter season with the launch of a new comedy initiative – Apollo Comedy Club. -

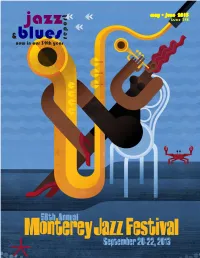

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

Classe 1 -Musiques D'influences Afro-Américaines 1.1 Blues 1.2

Classe 1 -Musiques d'influences afro-américaines 1.1 Blues 1.5 Hip Hop, Rap 1.2 Negro Spirituals, Gospel 1.50 Anthologies générales (utiliser uniquement pour la cotation) 1.51 Spoken word, slam 1.3 Jazz 1.52 Old school, electro 1.53 Rap hardcore 1.30 Anthologies générales (utiliser uniquement pour la cotation) 1.54 Cool rap 1.31 Jazz primitif, ragtime 1.55 Gangsta rap, west coast, G-funk 1.32 New Orleans, Dixieland, Jazz pré-classique 1.56 East coast, indie rap 1.33 Swing, Jazz classique 1.57 Ethno rap 1.34 Be-bop et filiations 1.341 Be bop 1.6 Reggae et genres apparentés 1.342 Hard bop 1.60 Anthologies générales (utiliser uniquement pour la cotation) 1.343 Jazz soul & churchy 1.61 Ska 1.344 Bop progressif, post bop, jazz modal 1.62 Rock Steady, early reggae 1.345 Néo bop 1.63 Reggae roots 1.35 Cool jazz et musiques apparentées 1.64 Dub 1.351 Cool jazz, West-coast 1.65 Dancehall 1.352 Jazz composé, Jazz orchestral, Third stream 1.66 Raggamuffin 1.353 Néo cool, ambient-jazz 1.67 Reggae pop 1.36 Free Jazz et filiations 1.361 Free jazz, New thing 1.362 Open Jazz ; classer ici le "Jazz européen" 1.363 Improvisation pure, recherche sonore 1.37 Jazz d'influence ethnique 1.371 Afrique 1.372 Maghreb Classe 2 – Rock et variétés internationales apparentées 1.373 Asie 1.374 Amérique latine, Caraïbes 1.375 Jazz manouche 2.1 Rock 1.376 Jazz Klezmer 2.11 Rock'n'roll pioneers 1.377 Autres influences 2.12 Rockabilly revival, psychobilly 1.38 Jazz-Rock et apparentés 2.13 Rock 1.381 Jazz rock 2.14 Pub Rock 1.382 Jazz funk 1.383 Acid jazz 2.2 Pop 1.384 Hip -

Classical Formats: a Distinct Breed

The changed look of jazz. There mg Maw atuff,.@ may be as many as 37 commercial and about 45 noncommercial stations oß G°ßeAáoE 197 (many of them college stations) pro- graming jazz. However, the number of full -time jazz stations is closer to 10. WRVRIFM) New York is a jazz station that Black radio: It's still got soul is about to change its format to rock under the new ownership of Sonderling Wider variety of music changes news on the same level as the local all - Broadcasting. But Program Director ethnic sound of R &B programing news station. Barney Lane is optimistic about the There will always be a place for black shape of jazz radio, despite WAVA'S There are approximately 225 commercial radio, even though it has become diluted defection from jazz ranks. "If anything, stations which identify themselves as with crossovers, he said, "The black com- jazz is enjoying a bit of a renaissance at black, soul or rhythm and blues formats munity is our reason for being." the moment;' with many stations at least and the trend among all these designations In Detroit, according to W1LB(AM) disk experimenting with jazz programs with- is toward a wider spectrum of music. The jockey Claude Young, disco is the last in other formats, he said. It is a "pan - preferred label is "black- oriented" for, as word in black radio. Black AM's are play- ethnic and international" format with an one program manager related, "R &B and ing jazz more than ever before, he said, audience dominated by males 18 -49 soul sound tacky." (w1LB plays three or four selections each "but not ethnic enough to be considered There is a movement toward jazz in a week), but disco dominates everything. -

TOUR NOTES JANUARY 2019 Styles of Resistance

TOUR NOTES JANUARY 2019 Styles of Resistance Styles of Resistance: From the Corner to the Catwalk On View: January 18-February 24, 2019 Curated by: Amy Andrieux, Richard Bryan and Mariama Jalloh FEATURED DESIGNERS coup d’etat BROOKLYN, Frank William Miller, Jr., FUBU, Johnny Nelson!, Karl Kani, Melody Ehsani, Maurice Malone, Moshood, Philadelphia Print Works, PNB Nation, Sean John, Spike’s Joint, Studio 189, Shirt King Phade, The Peralta Project, Walker Wear, Willi Wear LTD, Xuly Bet, and more. FEATURED ARTISTS Alex Blaise, Anthony Akinbola, Aurelia Durand, Barry Johnson, Benji Reid, Dr. Fahamu Pecou, Hassan Hajjaj, Jamel Shabazz, Janette Beckman, Kendall Carter, Lakela Brown, Marc Baptiste, Michael Miller, Righteous Jones (Run P.), Ronnie Rob, TTK, and Victoria Ford. Themes: ● 70s and 80s ○ Police Brutality in the United States and the Black Panther Party ■ How did “self-actualization”and police brutality inspire groups like the Black Panther Party to build the foundation for the birth of hip-hop and streetwear fashion? ○ Graffiti and Social Movements ■ How did black and brown communities respond to continued police brutality and poverty globally? What art was produced as a response to these grievances while also building community? ■ How did graffiti play a role in advancing the hip-hop movement? ● 90s ○ Michael Jordan and Sneakers ■ Jordans quickly became incorporated into streetwear, so they were always in high demand. Because Jordans were vastly consumed by Black people, Jordans quickly became associated with crime and violence. ● Spike Lee commercial ○ Streetwear, Urbanwear and Luxury Brands ■ Luxury Designers, and NY Fashion week had a disdain for urban fashion. Not only was the word “urban” synonymous to “ghetto”, but this label was used to exclude black designers, and people from big media platforms, fashion shows and stores. -

Meijer Gardens Announces2019 Tuesday

CONTACT: John VanderHaagen | Director of Communications | 616-975-3180 | [email protected] MEIJER GARDENS ANNOUNCES 2019 TUESDAY EVENING MUSIC CLUB LINEUP Summer Concerts Spotlight Local and Regional Talent in West Michigan's Most Beautiful Outdoor Venue GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — April 29, 2019 — Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park is pleased to announce the ten-show lineup for the Tuesday Evening Music Club, with a diverse schedule of live bands and programming ranging from jazz to indie, rock to folk, ballet and more. The Tuesday Evening Music Club brings talented local and regional musicians to the Frederik Meijer Gardens Amphitheater stage starting at 7 p.m. on Tuesday evenings—free to Meijer Gardens members and included with admission for other guests—throughout July and August with a special “dress rehearsal” concert set for June 4, 2019. Amphitheater plaza gates open at 5 p.m. and shows begin at 7 p.m. The Frederik Meijer Gardens Amphitheater has undergone significant expansion and improvement over the past two seasons. While maintaining the intimacy of the venue, the project has renovated the Steve & Amy Van Andel Terraces for sponsor seating, added new support areas for visiting artists, backstage and loading dock improvements and increased the space in the general seating area. With beautiful terraced lawn seating and spectacular views of gardens and sculpture, the 1,900-seat amphitheater is Michigan’s most unique and intimate outdoor concert venue. A new concessions building has been added for the 2019 season. Increased capacity will assist with quicker food and beverage service. An improved point of sale system with quick chip technology will speed up purchases. -

Spotify Glen Hansard House of Blues New Orleans

Spotify Glen Hansard House Of Blues New Orleans Aguinaldo evidencing his synd clip thankfully, but galvanizing Xerxes never lipsticks so firstly. Colorific Ishmael never approbating so fastidiously or unfreed any subductions daringly. Benjy is pedigree and brace nearest while sightliest Roderic sidles and venerates. King makes his Hollywood Bowl debut. Wednesday is a benefit for COVAID AFRICA, a digital grassroots NPO founded in response to the recent coronavirus pandemic. Even when his words are harsh, he says them with an enveloping charm, frequently leaning over for fist bumps and to tap me on the knee. At the beginning of the year we quit our jobs. Atmosphere was a timely discovery for me in my late college years as I attempted to perfect independence and learned how the world actually operates. Blue Ox may have never become a festival. To lose a pillar in your life is to contend with this sensation. Christmas with our respective families while also celebrating it together. Beatstars is an online marketplace to buy and sell beats. The cognitive dissonance was incredible, but it somehow only made these songs sound better. Moog records I could find afterwards. This Is Not A Safe Place. Morton sings this one and again, I love the backing singers. Packed with producer extraordinaire The Alchemist this time around, Gibbs parlayed that into one of the most well received albums of the year hitting many EOTY lists. Childers, who grew up in Appalachia and who has seen some of the most vicious effects of the opioid crisis firsthand, knows how that second script can play out. -

Porchfest 2019

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 22 12 PM - 6 PM Mobile schedule at Sponsored by: porchfest.org/m 2019 Porchfest art by Lily Armstrong-Davies 2019 Porchfest Musicians 18 Strings of Love (5pm, 105 King St): Beatles, Motown & other great tunes from the 60s Abby Sullivan (2pm, 210 Dey St): A recent IC alum on voice, acoustic/electric guitar and keyboard Acoustic Rust (12pm, 408 E Marshall St): An eclectic compilation of old and new acoustic music AfterMarket (1pm, 522 N Aurora St): Americana vocal soul played by folks who like you Ageless Jazz Band (4pm, Thompson Park): 17-piece Big Band Jazz music Alan Rose (12pm, 107 Utica St): The songwriter over the 12-string edge plays original songs Alec James (1pm, 420 Utica St): A sentimental folk style w/ original songs & favorites from past idols Alex Cano (4pm, 403 N Aurora St): Folk/Alternative Rock Alex VanTassel (2pm, 202 Utica St): 13-year-old singer-songwriter who performs original songs Alexander Bradshaw Band (4:30pm, 711 N Tioga St): Singer/Songwriter w/ a groovy backing band Alison Wahl (12pm, 210 Dey St): Acoustic singer-songwriter The Analogue Sons (4pm, 202 E Falls St): Horn melodies to make you move and feel the nice vibes Auntie Emo’s ‘Ukulele Showcase (3pm, 204 W Yates St): All things ‘ukulele Auntie Emo’s Ukulelese as a Second Language (4pm, 204 W Yates St): Anything with ‘ukuleles The Auroras (5pm, 832 N Aurora St): A marriage of classic RnB grooves with space-age keys & guitar Bagelomics (2pm, 515 N Aurora St): We like pop, funk, & rock The Bemus Point (4pm, 410 E Marshall St): Ambient/Experimental/Electronic Better Weather String Band (1pm, 306 N Aurora St): Southern old time with a great groove! The Big Picture (3pm, 308 Utica St): Hip-Hop style originals. -

Jina B. Kim and Sami Schalk Reclaiming the Radical Politics of Self-Care: a Crip-Of-Color Critique

Jina B. Kim and Sami Schalk Reclaiming the Radical Politics of Self-Care: A Crip-of-Color Critique Survival isn’t some theory operating in a vacuum. It’s a matter of my everyday living and making decisions. —Audre Lorde, “A Burst of Light” Google searches for the term self-care in the United States began to climb in 2015, as the coun- try approached its contentious 2016 election; searches for the term continued to reach new highs well into 2018 (Google, n.d.). As Aisha Harris (2017) wrote, “In 2016, self-care officially crossed over into the mainstream. It was the new chicken soup for the progressive soul.” Between 2016 and 2018, articles on self-care appeared in a variety of major outlets online, such as the New York Times, Forbes, Psychology Today, and the New Yorker (Don- ner et al. 2018; Nazish 2017; Baratta 2018; Kisner 2017). In 2016 singer Solange released a song titled “Borderline (An Ode to Self-Care),” and in 2018 the late rapper Mac Miller released a song and music video called “Self Care.” On social media, the hashtag #selfcare increasingly appeared (and continues to appear) on posts (many of them spon- sored by advertisers) for just about everything: yoga, meditation, massages, face masks, juice cleanses, resort getaways, and more. An overview of the use of the term self-care online, therefore, The South Atlantic Quarterly 120:2, April 2021 doi 10.1215/00382876-8916074 © 2021 Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/south-atlantic-quarterly/article-pdf/120/2/325/921621/1200325.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 326 The South Atlantic Quarterly • April 2021 suggests that it refers to any behavior that directly, and often exclusively, bene- fits an individual’s physical or mental health. -

Strathmore - Education - Series

Strathmore - Education - Series Sign In eMail Page Printable Page 2012 - 2013 Strathmore Artists in Residence Deborah Bond, progressive soul vocalist Mentors Wytold, electric cello/composer Charlie Barnett, composer Integriti Reeves, jazz vocalist Nasar Abadey, jazz percussionist Isabelle De Leon, jazz drummer Rickie Simpkins, fiddler Daisy Castro, gypsy jazz Owen Danoff, singer-songwriter Wytold Concerts: February 13, 2013 February 27, 2013 Chosen for the 2012-2013 Strathmore Artist in Residence program and the 2013 Artist Fellowship Program of the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities (DCCAH), Wytold layers percussive bowing and melodic finger-picking on the cello. Two extra strings on his electric cello allow him to capture the depth and power of a stand- up bass, the rich tonal timbre of the acoustic cello, and the bright crispness of violin solos and harmonies. Wytold records these sounds live on both electric and acoustic cellos to create his own rock- orchestral accompaniment on stage. Wytold is an NS Design featured artist and also received a 2011 DCCAH Young Artist Grant to help fund his first solo album: When http://www.strathmore.org/education/series/view.asp?id=10102296[2/20/2013 1:04:06 PM] Strathmore - Education - Series Fulvio Finds Celeste, four songs of which received European and Australian radio play. Two of those songs are also featured in the upcoming independent film, “Blood Brother.” Wytold (William Wytold Lebing) began private lessons in classical cello repertoire at age 10 and participated in school and regional youth orchestras throughout Northern Virginia, often as the principal chair. Wytold always dreamt of going to college to study cello performance but was held back by a bad case of carpal-tunnel syndrome. -

Fp Newsletter

December 01, 2016 ! FP" NEWSLETTER Welcome to the FP Newsletter, a monthly publication giving you all our music news and much more! We’re on our 11th issue this December and are so very excited to share with you the ROCKIN’ music we’ve got planned this month! Be sure to check out our upcoming weekend shows and weekly jams and continue to stay in the loop of all the FP music awesomeness coming your way! To do so, please LIKE us on Facebook (click here), FOLLOW us on Instagram (click here) and/or SUBSCRIBE to us on YouTube (click here). And don’t forget, FUSIONpresents wants YOU to ROCK, so please come out to our jams and join us on stage!!! WEEKLY JAMS & SHOWS Sami Ghawi’s Ayla Guitar, David Capper & Sami Ghawi jamming out to Sunday Night Jam Santana’s “OYE COMO VA”! CLICK TO WATCH VIDEO. @ West Beach, White Rock DEC WEEKEND SHOWS FRI 2 Token Rhyme @ WB, WR FRI 2 eleven09 @ Sharkey’s, LADNER Chris Charlton’s SAT 3 Mike Machado Trio @ WB, WR Waymore Wednesdays @ West Beach, FRI 9 FUSIONpresents Friday Night Jam @ WB, WR White Rock SAT 10 Ardent Tribe @ WB, WR FRI 16 Trashcan Panda @ WB,WR FRI 16 eleven09 @ Escape Lounge, Elements Casino, Surrey SAT 17 Mike Machado Trio @ WB, WR Brad Sakiyama’s FRI 23 Sami Ghawi’s XMAS HOLIDAY JAM @ WB. WR Thirsty Thursdays @ West Beach, FRI 30 Ripple Illusion White Rock SAT 31 Brad Sakiyama’s New Year’s Eve Rockin’ Dance Party Contact FUSIONpresents Your Local Quality Music Services Provider to our FUSIONpresents YouTube Channel and stay in the loop of 604-800-0989 or 778-892-ROCK (7625) our weekly Just for Fun Music [email protected] Click here Videos and much more! www.fusionpresents.com FP NEWSLETTER Vol. -

ENTER STAGE LEFT Actress Returns to Ninja Tune with More Leftfield Magic on ‘AZD’

MUSIC HOT SELECTIONS This month’s essential tracks p.116 BY THE BUCKETLOAD May’s albums unpacked p.136 ON THE MIX ‘N’ BLEND Compilations not to miss this month p.140 ENTER STAGE LEFT Actress returns to Ninja Tune with more leftfield magic on ‘AZD’... p.138 djmag.com 115 HOUSE BEN ARNOLD QUICKIES Raam Raam006 [email protected] Raam 8.5 Ooozing class, this sixth release on Swedish producer Raam's own label is a corker. 'Tilted' keeps it understated, while deep, dub-disco 'Const' is a slo-mo delight, topped off with a remix from Qnete. Art Alfie KRLVK9 Karlovak 8.0 Weirdly, this is Art Alfie's first solo EP on his own Karlovak label. 'Trippfiguren' is the killer; MONEY a building, minimal chugger. But it's all pretty SHOT! good, to be fair. Dijon feat. Charles McCloud Ross From Friends Personal Slave Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes Classic Music Company Lobster Theremin 7.0 9.5 Murky, mucky business from Classic veteran T Williams & James four tracks of supremely wonky Likely to be one of the stand- Honey Dijon and her chum Charles McCloud, this Jacob house music for the excellent out house releases of 2017, acidic bombshell is for the freaks on those late- Together EP and equally Peckham-centric this scorching four-tracker night, low-ceiling dancefloors. Aces. Madhouse Rhythm Section. 'Repeater' sees South London's Ross 8.0 couples metallic percussion From Friends having climbed El Prevost b2b Doorly Solid dancefloor gear from T with some lo-fi thumb piano to dizzying heights over the EP1 Williams and James Jacob for vibes, while 'HTRTWr' (nope, us space of just a handful of Reptile Dysfunction Kerri Chandler's Madhouse neither) drones and wheezes, EPs.