Joseph Smith, Now Cast in Bronze, Returns to New York City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

32OS Digital Brochure 190314-3

— Highly efficient floorplates Welcome to 32 Old Slip — 360 degree views — State of the art infrastructure — Column free floors — 13'6"+ slab heights 32 OLD SLIP 2 — Lobby coffee bar Amenities — Lobby art programs & communal space & Infrastructure — Building wide socials and fitness programs — Convene™ meeting and event space — Bike room and exclusive parking garage Artist rendering of proposed lobby program 32 OLD SLIP 3 — 500+ bars and restaurants Neighborhood — 1,170 retailers — 31 hotels — 84+ acres of outdoor space — 300,000 daily commuters — 14.8 million visitors per year 32 OLD SLIP 4 Y A W D A O R B . T E S Y R LEO N A R D ST. H OG A N P L . N E H . H A R R I SO N ST. T S M N A R O K S E T I S D . T A T . M S E WO R TH ST. O . R T N S O M E O JAY ST. R L I T V T ER S N S E T E TH O M AS ST. C L P C M . A A A N T T T H H S E A S P E A R L ST. R I T T T T N E A N ST B ES . R I D UA N E ST. DG W E . T S R E T A W WA R R EN ST. A C N R . T E F R A N K F O R T ST. DOV ER ST. -

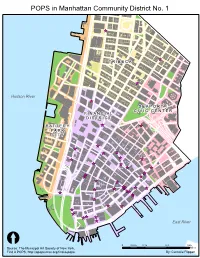

Manhattan Community District 1 Privately Owned Public

POPS in Manhattan Community District No. 1 ^_ ^_ T R II B E C A ^_ Hudson River ^_ S E A P O R T // C II V II C C E N T E R F II N A N C II A L D II S T R II C T B A T T E R Y ^_ ^_ P A R K C II T Y ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_^_ ^_^_^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_^_^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_^_ ^_ ^_ East River [ 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 0.45 Source: The Municipal Art Society of New York, Miles Find A POPS, http://apops.mas.org/find-a-pops. By: Cammie Flippen Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS) in Manhattan Community District No. 1 Year Disabled Location Space Type Size Completed Access Hours of Access Amenities (Required) Public Lobby 0 sf; Public Lobby, Pedestrian Pedestrian Easement 0 101 Barclay Street Easement sf 1983 Full/Partial 24 hours Trees on street, trees within space 1 Battery Park Plaza Plaza Plaza 16,337 sf 1969 Full/Partial 24 hours No legally required amenities Plaza 11,292 sf; Arcade 17 Battery Place Plaza, Arcade 7,280 sf 1972 Full/Partial 24 hours No legally required amenities Lighting, litter receptacle, planting, Urban Plaza 1,584 sf; plaque/sign, seating, trees on street, trees 40 Broad Street Urban Plaza, Arcade Arcade 745 sf 1983 Full/Partial 24 hours within space 55 Broad Street Arcade 4,089 sf 1966 Full/Partial 24 hours No legally required amenities Urban Plaza 9,630 sf; Lighting, litter receptacles, plaque/sign, Sidewalk Widening retail frontage, seating, trees on street, Urban Plaza, Sidewalk 3,600 sf; Arcade 12,930 trees within space, other: signage and Widening, Arcade, sf; Publicly Accessible display methods -

THE VERIZON TELEPHONE COMPANIES TARIFF F.C.C. NO. 21 1St Revised Page 4-1 Cancels Original Page 4-1

THE VERIZON TELEPHONE COMPANIES TARIFF F.C.C. NO. 21 1st Revised Page 4-1 Cancels Original Page 4-1 SPECIAL CONSTRUCTION (D)(x) (S)(y) 4. Verizon New York Inc. Special Construction Cases 4.1 Charges for the State of Connecticut (Company Code 5131) 4.1.1 Special Construction Cases Prior to May 25, 1984 The following cases are subject to the regulations specified in 2.1 through 2.8 preceding, with the following exception. When the initial liability period expires, an annual underutilization charge applies to the difference between 70% of the number of original specially constructed facilities and the number of facilities in service at filed tariff rates at that time. For purposes of determining the underutilization charge, any facilities subject to minimum period monthly charges are considered to be in service at filed tariff rates. There are no special construction cases prior to May 24, 1984 for the State of Connecticut. (S)(y) (D)(x) (x) Filed under authority of Special Permission No. 02-053 of the Federal Communications Commission. (y) Reissued material filed under TR 169, to become effective on April 13, 2002. (TR 176) Issued: April 11, 2002 Effective: April 13, 2002 Vice President, Federal Regulatory 1300 I Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20005 THE VERIZON TELEPHONE COMPANIES TARIFF F.C.C. NO. 21 8th Revised Page 4-2 Cancels 7th Revised Page 4-2 SPECIAL CONSTRUCTION 4. Verizon New York Inc. Special Construction Cases (Cont'd) 4.1 Charges for the State of Connecticut (Company Code 5131) (Cont'd) 4.1.2 Charges to Provide Permanent Facilities Customer: Greenwich Capital Markets ID# 2003-264110 Description: Special Construction of facilities to provide fiber based telecommunications services at 600 Steamboat Road, Greenwich, CT 06830. -

Skyline 2014

skyline REAL ESTATE YEAR-IN-REVIEW 2014 PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, WHARTON & GARRISON LLP © 2015 Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP In some jurisdictions, this brochure may be considered attorney advertising. Past representations are no guarantee of future outcomes. SKYLINE REAL ESTATE YEAR-IN-REVIEW 2014 Friends, Clients, Colleagues, We are extraordinarily grateful to have had the privilege of working with some of the nation’s top residential and commercial developers and owners, as well as government entities and non-profit institutions, entrepreneurs and investors in their most important transactions this past year – and what a year it has been! New York is the city of dreams, and our clients are in the business of turning dreams into reality, breaking new ground last year on unprecedented development projects and residential, commercial and retail construction that will transform the neighborhoods and skyline of the City. Abundant investment capital and funding combined with low interest rates and a safe haven for foreign capital are fueling investor demand for New York real estate. The bustling activity in the City’s office, residential and hospitality sectors attracts people from all over the world to live, invest and visit. This is an extraordinary time – and we look forward to helping our clients take advantage of emerging opportunities in the coming years. Steven Simkin Chair of the Paul, Weiss Real Estate Department contents Development 2 Sales, Acquisitions & Joint Ventures 8 Hospitality & Gaming 14 Financing 18 Leasing & Ground Leasing 20 Kohn Pedersen Fox development New Office Tower Planned in Midtown Manhattan We represent the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in the pre-development aspects for a new office tower known as One Vanderbilt, to be constructed by Hines and SL Green at 42nd Street and Vanderbilt Avenues subject to favorable zoning and land use review. -

888-730-7307 Locations

CONVENE.COM | 888-730-7307 Locations New York City Financial District Midtown West Midtown East Midtown East 32 Old Slip, 117 W 46th Street, 780 Third Avenue, 730 Third Avenue New York, NY 10005 New York, NY 10036 New York, NY 10017 New York, NY 10017 Capacity: 2-250 Capacity: 2-700 Capacity: 2-200 Capacity: 2-400 Meeting Rooms: 12 Meeting Rooms: 5 Meeting Rooms: 5 Meeting Rooms: 1 Space: 39,000 sq. ft. Space: 35,000 sq. ft. Space: 11,000 sq. ft. Space: 40,000 sq. ft. Midtown East Financial District Grand Central Times Square 237 Park Avenue, One World Trade Center 101 Park Avenue, 810 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Condé Nast Venues New York, NY 10017 New York, NY 10019 New York, NY 10007 Capacity: 2-275 Capacity: 2-144 Capacity: 2-210 Meeting Rooms: 9 Capacity: 2-260 Meeting Rooms: 8 Meeting Rooms: 8 Space: 30,000 sq. ft. Meeting Rooms: 14 Space: 20,000 sq. ft. Space: 23,000 sq. ft. Space: 12,000 sq. ft. Philadelphia Commerce Square Cira Centre CityView 2001 Market Street, 2929 Arch Street, 30 South 17th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103 Philadelphia, PA 19104 Philadelphia, PA 19103 Capacity: 2-170 Capacity: 2-455 Capacity: 2-175 Meeting Rooms: 16 Meeting Rooms: 14 Meeting Rooms: 9 Space: 24,000 sq. ft. Washington D.C. Boston Tysons Corner Financial District 1800 Tysons Blvd, One Boston Place McLean, VA 22102 201 Washington Street, Boston, MA 02108 Capacity: 2-250 Meeting Rooms: 6 Capacity: 2-175 Space: 15,000 sq. ft. Meeting Rooms: 6 888-730-7307 CONVENE.COM Services Hosting successful meetings and receptions is effortless with Convene’s vertically integrated services. -

Lower Manhattan Real Estate Market Report

OFFICE RETAIL HOTELS + TOURISM RESIDENTIAL MAJOR PROJECTS UPDATE Q2 2020 LOWER MANHATTAN REAL ESTATE MARKET REPORT Lower Manhattan Real Estate Market Report | Q2 2020 1 OFFICE RETAIL HOTELS + TOURISM RESIDENTIAL MAJOR PROJECTS UPDATE Q2 2020 LOWER MANHATTAN REAL ESTATE MARKET REPORT Leasing Activity Slows Dramatically As Lower Manhattan Annual New Leasing Economic Uncertainty Persists Activity, 2015-2020 The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed the world into Source: CBRE unprecedented public-health and economic crises. New York City emerged as the epicenter of the pandemic in the second quarter, with lockdowns keeping all but only essential workers at home. While Lower Manhattan’s office market performed well in early 2020, momentum slowed considerably in March and halted almost entirely for much of the second quarter. Office leasing is expected to be low well into the second half of 2020, and increased subleasing may create downward pressure on rents later in the year. After six consecutive quarters during which new leasing activity was greater than one million sq. ft., the second quarter saw Lower Manhattan office leasing slow to just 516,000 sq. ft. Leasing activity was down 56% from the first quarter and 60% below the five-year quarterly average as real estate decisions were put on hold. Monthly leasing figures continued to drop after limited reopenings, with just 52,000 sq. ft. of new leasing activity in June. The dual public-health and economic crises saw dramatic slowdowns across all major American office markets. Midtown Manhattan saw below-average leasing with 1.29 million sq. ft. of leasing activity, dropping 68% year-over- year and 69% behind the five-year quarterly average. -

4.5 MILLION SF Surpassed 2016’S Total

OFFICE RETAIL TOURISM & HOSPITALITY RESIDENTIAL MAJOR PROJECTS UPDATE ALLIANCE FOR DOWNTOWN NEW YORK LOWER MANHATTAN REAL ESTATE MARKET REPORT Q3 2017 LOWER MANHATTAN ON TRACK FOR STRONG YEAR END FINISH LOWER MANHATTAN LEASING ACTIVITY SURPASSES 2016 TOTAL IN THIRD QUARTER Lower Manhattan logged another positive quarter in 2017, positioning the market for its best year since 2014. The Lower Manhattan’s commercial office market is experiencing its area’s vacancy rate dropped for the third consecutive strongest year since 2014 and continued to perform well in the quarter making Lower Manhattan the 15th tightest third quarter. Activity was up 20 percent over last quarter. Lower submarket nationwide, according to Cushman & Wakefield. Manhattan logged 1.43 million square feet of new activity in Lower Manhattan’s status as the third quarter, bringing the year-to-date volume to 4.5 million a media mecca reached new square feet. According to CBRE, heights with ESPN Studios’ year-to-date activity has already announced relocation to the 4.5 MILLION SF surpassed 2016’s total. Seaport District’s Pier 17, as well as Macmillan Publishers’ Highest YTD Leasing Activity While leasing activity is up year-over-year Manhattan-wide, commitment to relocate its since 2014 headquarters from the Flatiron Lower Manhattan’s 56 percent Building to 120 Broadway. year-over-year jump far outpaces Investment activity in the office market is higher than 2016 other market’s performance as compared to this time last year. activity, with several large deals demonstrating investors’ Midtown activity is up 20 percent, bolstered by strong activity at positive outlook on the market. -

Lower Manhattan Real Estate Market Report Q3 2018

OFFICE RETAIL TOURISM & HOSPITALITY RESIDENTIAL MAJOR PROJECTS UPDATE ALLIANCE FOR DOWNTOWN NEW YORK LOWER MANHATTAN REAL ESTATE MARKET REPORT Q3 2018 CHANGE IN OCCUPANCY 2008 - 2018 TAMI 10 pts FIRE 20 pts GOVT 6 pts PROF 3 pts FASHION 1 pt EDU 2 pts HEALTH 1 pt Years After the Financial Crisis, 10 Lower Manhattan Office Occupancy is More Diverse than Ever. Lower Manhattan’s office occupancy 11, 2001. Most notably, the Technology, companies like the Associated Press, the experienced a dramatic transformation in Advertising, Media and Information sectors Meredith Corporation (formerly Time Inc.), the ten years since one of the worst financial (TAMI) occupy triple the share of space the College Board and J.Crew as some of its crises in history rocked the market. today that they did in 2008 - 5 percent vs biggest occupants. This diversification is also The Finance, Insurance and Real Estate 15 percent. A flurry of nonprofit, healthcare, apparent in employment trends. Professional (FIRE) industry’s historic dominance of and professional services companies have Services employment is at its highest level in Lower Manhattan’s office market has given moved to Lower Manhattan helping to grow LM since at least 2001 - 51,332 employees, way to a more diverse tenant mix. Lower these sectors’ share of the office market up nearly 50 percent since the depths of Manhattan’s economy is more vibrant and as well. This transformation is evident in the recession in 2009. Information sector dynamic today than at any time in the buildings across the district. The World Trade employment, which includes jobs in media more than twenty years since the Center campus (One, 3 and 4 World Trade and publishing, is just 5 percent off from creation of the Downtown Alliance. -

Foreign Exchange Committee 2007 Annual Report

Member List, 2008 Shigeru Asai Peter Connolly Russell LaScala General Manager and Treasurer Executive Vice President Managing Director Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Wells Fargo Deutsche Bank 1251 Avenue of the Americas 1 Front Street 60 Wall Street New York, New York 10020 San Francisco, California 94111 New York, New York 10005 212-782-4995 415-396-4591 212-250-4203 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Term: 2008-2011 Term: 2006-2009 Term: 2007-2010 Anthony Bisegna Jeff Feig Michael Leibowitz Senior Managing Director Managing Director Chief Executive Officer State Street Corporation Citigroup TFS Brokers 1 Lincoln Street 390 Greenwich Street East India House Boston, Massachusetts 02111 New York, New York 10013 117-119 Middlesex Street 617-664-1190 212-723-7618 London E1 7JF [email protected] [email protected] United Kingdom Term: 2007-2010 Term: 2005-2008 44-20-7198-1550 [email protected] Graham Broyd Rodolfo Fischer Term: 2007-2010 Managing Director Executive Vice President RBS Greenwich Capital Banco Itau S.A. Richard Mahoney 600 Steamboat Road Av. Eng. Armando de Arruda Pereira Executive Vice President Greenwich, Connecticut 06830 São Paulo 04344-902 The Bank of New York 203-618-6325 Brazil 32 Old Slip [email protected] 55-11-5029-3780 New York, New York 10286 Term: 2007-2010 [email protected] 212-804-2018 Term: 2008-2011 [email protected] David Castle Term: 2005-2008 Managing Director Susan Gammage Standard Chartered Bank Executive Vice President Frank Manganella 1 Madison -

Shop. Eat. Drink. Play

Tickets available at ONEWORLDOBSERVATORY.COM SHOP. HOW DO YOU GET TO THE TOP OF THE CITY’S TALLEST BUILDING? EAT. IN A SKYPOD, OF COURSE. DRINK. PLAY. ALL UNDER ONE Guide Manhattan Shop Dine Lower MAGNIFICENT ROOF. At the corner of Church St. and Dey St. LOWER MANHATTAN SHOP DINE GUIDE 2018 | 2018 DOWN IS WHAT’S UP!TM @ONEWORLDNYC BANANA REPUBLIC | EATALY | FOREVER 21 #ONEWORLDVIEW SEPHORA | UGG | VICTORIA’S SECRET Where the Palm Trees Grow. Fashion. Food. Art Vesey & West St When it comes to fashion and beauty, we are now poised to become one of the pre-eminent shopping destinations in the region. A year after the Oculus and Westfield World Trade Center opened, Saks Men (following on the heels of Saks Women), Marshalls, Dior Cosmetics, and Allen Edmonds joined T.J. Maxx, Century 21, and the shops at Brookfield Place. What will next year bring? Looking ahead, restaurateurs Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Danny Meyer, and the duo of Will Guidara and Daniel Humm plan to open new restaurants in Lower Manhattan. And when Alamo Drafthouse opens its doors to moviegoers at 28 Liberty, it will join the Seaport’s iPic Theater in making the neighborhood a destination for those SHOPPING who want to mix great food and drink with catching a flick. Just like you can’t tell the players in a baseball game without a scorecard, sometimes it can be hard to keep track of all the & DINING new options in the neighborhood. With that in mind, we present you with the Downtown Alliance’s 2018 Lower Manhattan IN LOWER MANHATTAN Shop Dine Guide -- your best source for shops, eateries, bars, From the Statue of Liberty to the observation deck at One museums, community resources, attractions and more. -

Manhattan Community Board 1 Full Board Meeting

Manhattan Community Board 1 Full Board Meeting Wednesday, March 27, 2013 6:00pm Silverstein Properties 7 World Trade Center, 10th Floor Manhattan Community Board 1 Public Session • Comments by members of the public (Please limit to 1-2 minutes per speaker, to allow everyone to voice their opinions) Manhattan Community Board 1 Business Session • Adoption of February 2013 minutes • Chairperson’s report – C. McVay Hughes • District Manager’s report – N. Pfefferblit • Treasurer’s Report – J. Fratta Manhattan Community Board 1 Committee Reports Board Accomplishments for 2012 Responded to the emergency caused by Superstorm Sandy in numerous ways, including the following: • Organized an emergency Executive Committee meeting at Trinity Church on Sunday, November 4, 2012 to hear from and share information with residents and businesses while CB1 office was closed since it had no power, heat, data or phone service. • Gathered information on residential and commercial buildings without electricity, steam (heat and hot water), landline and data services to share with City agencies, elected officials, utility companies and the Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center so the situation could be rectified. • Organized a town hall meeting on November 19, 2012 which brought many government agencies to over 125 people in a packed Southbridge Towers Community Room in the Seaport area, the most severely impacted by the storm. • Adopted Emergency Preparedness: Lessons Learned from Superstorm Sandy, a report with numerous recommendations about how to improve emergency responsiveness and overall resiliency for our district in the future. • Formed a Disaster Relief Small Business Task Force to help businesses impacted by the storm. • Successfully advocated for FEMA to open a Recovery Center in CB1 in the Seaport area, the only center in Manhattan. -

Lower Manhattan Real Estate Year in Review 2016

ALLIANCE FOR DOWNTOWN NEW YORK LOWER MANHATTAN REAL ESTATE YEAR IN REVIEW 2016 Photo by Mark Weinberg, for Utopia, The Agency OFFICE RETAIL TOURISM & HOSPITALITY RESIDENTIAL MAJOR PROJECTS UPDATE ALLIANCE FOR DOWNTOWN NEW YORK LOWER MANHATTAN REAL ESTATE YEAR IN REVIEW 2016 LOWER MANHATTAN CATCHES ITS BREATH In 2016, Lower Manhattan continued its decade-long existing Lower Manhattan tenants seizing opportunities to transformation into one of New York’s most vibrant, stay or expand in the neighborhood. In addition, current 24/7 neighborhoods. While commercial leasing mirrored and new media, tech and advertising tenants grew their the slowdown experienced throughout Manhattan, several presence but at a slower rate than past years. Droga5, existing Lower Manhattan tenants demonstrated their a Lower Manhattan TAMI tenant since 2014, expanded commitment to the district by renewing or expanding their by more than 100,000 square feet in early 2016. Other Lower Manhattan footprints. Additionally, a pipeline of smaller TAMI deals followed throughout the year, and late upcoming deals announced in 2016 will (if completed) take November brought exciting news reports about Spotify’s several large blocks of space off the market. As commercial rumored move to a new headquarters in 4 World Trade leasing took a breather, Lower Manhattan’s dining and Center. Lower Manhattan also began to reap the benefits retail scenes took off. Internationally renowned chefs opened of prior strong years as new tenants in growing industries some of 2016’s most anticipated new restaurants in Lower completed their moves to the district. These changes Manhattan, while Westfield World Trade Center brought world- continued to diversify the tenant mix and helped drive class retail to the stunning World Trade Center Transportation private sector employment to its highest level since the Hub.