Old 5Th Kentucky Mounted Infantry Regiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Floyd County Times

.. :;.... I -1'-f-fC/')L/ ' CDURTIN ' CHAIR ' FEATURE OF OLD HOUSE THAT NEVER M'.)VED, WAS IN 4 CDUNTIES by Remy P. Scalf (Reprinted from the Floyd County Times, January 14, 1954) In an old house, near the mouth of Breedings Creek in Knott County, live the five Johnsons--three brothers and two sisters --Patrick, John D. , Sidney, Elizabeth, and Allie. Four are unmarried. Patrick, the oldest, is 83. Portraits of their ancestors--Simeon Johnson, lawyer, teacher, and scholar; Fieldon Johnson, lawyer, landowner, and Knott ' s first County Attorney; and Fielding' s wife Sarah (nee Iot son)--look down upon them from the house ' s interior walls. Visitors to the Johnson hane are shown the family ' s most prized possessions and told sanething of their early history. Among the famil y ' s heirloans are their corded, hand-turned fourposter beds that were brought to the house by Sarah Johnson. 'Ihese came fran her first home, the Mansion House, in Wise, Virginia, after the death of her father, Jackie Iotson, Wise County ' s first sheriff. (The Mansion House was better knCMn as the Iotson Hotel, one of southwest Virginia' s famous hostelries. ) At least two of the beds she brought with her have names: one is called the Apple Bed for an apple is carved on the end of each post; Another is the Acorn Bed for the acorns carved on its posts. 'Ihe bed ' s coverlets were also brought fran Virginia along with tableware and sane pitchers lacquered in gold that came from her mother Lucinda ' s Matney family. Visitors are also shown the wedding pl ate, a large platter fran which each Johnson bride or groan ate his or her first dinner. -

Ickinstn:Y, Justus, Soldier, B. in New York About 1821. He Was Gra.Dua.Ted at the U

~IcKINSTn:Y, Justus, soldier, b. in New York about 1821. He was gra.dua.ted at the U. S. mili tary academy in 1888 and assigned to the 2d in fantry. He became 1st li eutenant, 18 April, 1841, and assistant quartermaster with the rank of cap tain on 3 March, 1847, and led a com pany of vol unteers at Contreras and Churubusco, where he was brevetted major for gallantry on 20 Aug., 1847. He participa.ted in the battle of Chapulte pec, and on 12 Jan., 1848, became captain, which post he vacated and served on quartermaster duty with the commissioners that were running the boundary-lines between the United States lind Mexico in 1849- '50, and in Califol'l1ia in 1850-'5. He became quartermaster with the ra.nk of major on 3 Aug., 1861, fl.nd was stationed at St. Louis fl. ud fl.ttac hed to the staff of Gen. John C. Fremont. He combined the duties of provost-marshal wit.h those of qUfl.rteJ'lnaster of the Depaltment of the West, on 2 Sf'pt., 1861, was appointed Lrigadier genoml of volunteers, and commanded It division on Gen. Fremont's march to Springfield. lIe was a.ccused of dishonesty in his transactions as qua.r termaster, and was arrested on 11 Nov., 1861, by Gen. Hunter, the successor of Gen. Fremont, and ordered to St. Louis, Mo., where he was closely confin ed in the arsena.1. The rigor of his impris onment was mitigated on 28 Feb., 1862, fl.nd in May he was released 0n parol e, but required to re main in St. -

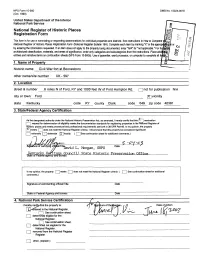

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "X" in the appn by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For fu architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place addi1 entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all it 1. Name of Property historic name Civil War fort at Boonesboro__________________________________ other name/site number CK - 597________________________________________ 2. Location street & number .6 miles N of Ford, KY and 1000 feet W of Ford Hampton Rd. Qnot for publication N/A city or town Ford [XI vicinity state Kentucky code KY county Clark code 049 zip code 40391 3. State/Federal Agency Certification \r __ As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ | nomination I I request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic places and meets procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property PM meets I I does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Demographics

Big Sandy Area Community Action Program Head Start 5-Year Head Start 2021 Big Sandy Area Community Action Program Head Start 2021 Community Assessment Update Foreword June 2021 The Big Sandy Community Action Program (BSACAP) Head Start 5-Year 2020 Community Assessment process was conducted during unprecedented times in the history of our nation. The world was experiencing a global pandemic due to the coronavirus, also referred to as COVID-19. Millions of Americans across the nation, including the Commonwealth of Kentucky and Eastern Kentucky lived through various stages of Shelter at Home/Healthy at Home and Healthy at Work orders there were implemented mid-March 2020 through June 11, 2021. Students in P-12 schools and colleges and universities received instruction through a variety of non-traditional methods during the 2020-21 school year, including online instruction and limited on-site class size using a hybrid method. Other than health care workers, first responders, and essential business workers (pharmacies, grocery stores, drive-through/curb side/delivery food service, gas stations, hardware stores, and agricultural businesses), all non- essential businesses in Kentucky were closed for three (3) months. Hundreds of thousands of workers applied for unemployment, Medicaid, and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits in a state system that was never designed to accommodate the level of need it has been experiencing. The federal government approved an economic stimulus package to help families and businesses. Child care centers, initially closed to all but health care workers, re-opened to a reduced number of children under strict state requirements and guidelines. -

Prestonsburg Tourism Commission 50 Hal Rogers Drive Prestonsburg, Kentucky 41653 (606) 886-1341 // 1-800-844-4704 Prestonsburgky.Org #Feeltheburg 2 Welcome

E-mail us for group travel opportunities. [email protected] prestonsburg WE LOOK FORWARD TO ACCOMMODATING YOU. explore Brookshire Inn & Suites 85 Hal Rogers Drive Prestonsburg, Kentucky 41653 (606) 889-0331 // 1-877-699-5709 brookshireinns.com Comfort Suites 51 Hal Rogers Drive Prestonsburg, KY 41653 (606) 886-2555 choicehotels.com/KY019 Quality Inn 1887 U.S. 23 N Prestonsburg, KY 41653 (606) 506-5000 choicehotels.com/KY267 Super 8 (Pet Friendly) 80 Shoppers Path // 550 U.S. 23 S Prestonsburg, KY 41653 (606) 886-3355 super8.com/prestonsburgky Jenny Wiley State Resort Park 419 Jenny Wiley Drive Prestonsburg, KY 41653 (606) 889-1790 // 1-800-325-0142 parks.ky.gov/parks/resortparks/ jenny-wiley/ Prestonsburg Tourism Commission 50 Hal Rogers Drive Prestonsburg, Kentucky 41653 (606) 886-1341 // 1-800-844-4704 prestonsburgky.org #feeltheburg 2 Welcome 4 Recreation 6 Entertainment 8 Outdoor Experiences 10 Outdoor The 2018 Travel Guide is published by Prestonsburg Tourism Commission. Every effort is made to ensure all the information in this guide is up-to-date and correct at the time Adventure of printing. All information is subject to change without notice. Photo credits: Michael Wallace, Kaye Willis 12 Culinary Experience prestonsburg 14 History explore 18 Events 3 PRESTONSBURGKY JOIN US FOR AN EASTERN KENTUCKY ADVENTURE .ORG restonsburg is the Star City of Eastern Kentucky and truly a jewel Pin the heart of the Appalachian CITY OF THE STAR mountains. The story of Prestonsburg, the first town established in eastern Kentucky, is one as old as the mountains themselves. The year was EASTERN KENTUCKY 1797 and a man by the name of John Graham from Virginia surveyed the land that became Prestonsburg. -

Understanding the First AIF: a Brief Guide

Last updated August 2021 Understanding the First AIF: A Brief Guide This document has been prepared as part of the Royal Australian Historical Society’s Researching Soldiers in Your Local Community project. It is intended as a brief guide to understanding the history and structure of the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War I, so you may place your local soldier’s service in a more detailed context. A glossary of military terminology and abbreviations is provided on page 25 of the downloadable research guide for this project. The First AIF The Australian Imperial Force was first raised in 1914 in response to the outbreak of global war. By the end of the conflict, it was one of only three belligerent armies that remained an all-volunteer force, alongside India and South Africa. Though known at the time as the AIF, today it is referred to as the First AIF—just like the Great War is now known as World War I. The first enlistees with the AIF made up one and a half divisions. They were sent to Egypt for training and combined with the New Zealand brigades to form the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). It was these men who served on Gallipoli, between April and December 1915. The 3rd Division of the AIF was raised in February 1916 and quickly moved to Britain for training. After the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula, 4th and 5th Divisions were created from the existing 1st and 2nd, before being sent to France in 1916. -

A State Divided: the Civil War in Kentucky Civil War in the Bluegrass

$5 Fall 2013 KentuckyKentucky Humanities Council, Inc. humanities A State Divided: The Civil War in Kentucky Civil War in the Bluegrass e are 150 years removed from the Civil War, yet it still creates strong emotions in many Americans. The War Between the States split the nation deeply and divided Kentucky, pitting friend against friend, neighbor against neighbor, brother against brother, and even father against son. WKentucky’s future was forever changed by the events of the Civil War. In commemoration of the Civil War’s sesquicentennial, we are pleased to share with you a wide array of Kentucky perspectives and issues that developed throughout the war. What would Abraham Lincoln say about slavery and the Civil War if he were alive today? Stephen A. Brown conducts a “conversation” with President Lincoln through chronicled speeches and writings. His article is on page 7. Camp Nelson played a pivotal role in the destruction of slavery in the Commonwealth. W. Stephen McBride shares the history of Kentucky’s largest recruitment and training center for Ben Chandler African American soldiers and what remains of Camp Nelson today. Executive Director John Hunt Morgan is widely known for his Confederate Cavalry raids, overshadowing fellow Kentucky Humanities Council Kentuckian George Martin Jessee, known as “Naughty Jessee.” Mark V. Wetherington tells us about the lesser known Confederate Cavalryman on page 15. While Kentucky’s men were off fighting for both the Union and the Confederacy, their wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters were left to take care of the family and home. On page 18, Nancy Baird shares the stories of several Kentucky women who bravely kept the home fires burning during the Civil War. -

Contents 1.0 Preface

Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War Council of Administration Report March 24, 2018 Brentwood, Tennessee Contents 1.0 Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 National Elected Officers ........................................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Commander-in-Chief; Mark R. Day, CinC ............................................................................................ 5 2.2 Senior Vice Commander-in Chief; Donald W. Shaw, PDC ................................................................... 7 2.3 Junior Vice Commander-in-Chief; Edward J. Norris, PDC ................................................................... 7 2.4 National Secretary; Jonathan C. Davis, PDC ........................................................................................ 7 2.5 National Treasurer;David H. McReynolds, DC .................................................................................... 8 2.6 National Quartermaster; Danny L. Wheeler, PCinC………………………………………………………………………10 2.7 Council of Administration – 2020; Kevin P. Tucker, PDC .................................................................. 10 2.8 Council of Administration – 2018; Brian C. Pierson, PDC.................................................................. 10 Recommendation ..……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 11 2.9 Council of Administration – Donald L. Martin, PCinC ...................................................................... -

Great War in the Villages Project

Great War in the Villages Project From the website of the Australian Light Horse Association http://www.lighthorse.org.au/ The Battle of Romani 4/5 August, 1916 ...suddenly, in the confused fighting, a large body of Turks punched a gap through the defenders and swept around the edge of a high escarpment hoping to come in on the Australians' rear. However, Chauvel had already stationed a handful of Australians on top of the precipitous slopes to guard against such a move. Now these men sprang into action... Soon after midnight on August 4, 1916, the dim shadows of Turkish soldiers darted across the Sinai Desert towards the Romani tableland. Ahead lay the isolated outposts of Major-General Harry Chauvel's Anzac Mounted Division, which barred the way to their objective, the Suez Canal. Towards dawn the Turkish army sighted the Australians. Charging forward, they sliced through the thin defences, annihilating the posts before any effective resistance could be organised. And thus began the bloody battle of Romani, a conflict which, after two days of murderous fighting, saw the Anzacs shatter forever the Turkish dreams of controlling the most vital man-made waterway on earth. After the evacuation of Gallipoli, Australian infantry divisions were transferred to the Western Front in France, although General Sir Archibald Murray, British commander in the Middle East, had fought bitterly against the move. Murray was not being pig-headed. Actually he expected the Turks to advance against Egypt at any moment and he felt he could hold the enemy only with the assistance of the battle hardened Australians. -

The Big Sandy

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1979 The Big Sandy Carol Crowe-Carraco Western Kentucky University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crowe-Carraco, Carol, "The Big Sandy" (1979). United States History. 31. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/31 The Kentucky Bicentennial Bookshelf Sponsored by KENTUCKY HISTORICAL EVENTS CELEBRATION COMMISSION KENTUCKY FEDERATION OF WOMEN'S CLUBS and Contributing Sponsors AMERICAN FEDERAL SAVINGS & LOAN ASSOCIATION ARMCO STEEL CORPORATION, ASHLAND WORKS A. ARNOLD & SON TRANSFER & STORAGE CO., INC. / ASHLAND OIL, INC. BAILEY MINING COMPANY, BYPRO, KENTUCKY / BEGLEY DRUG COMPANY J. WINSTON COLEMAN, JR. / CONVENIENT INDUSTRIES OF AMERICA, INC. IN MEMORY OF MR. AND MRS. J. SHERMAN COOPER BY THEIR CHILDREN CORNING GLASS WORKS FOUNDATION / MRS. CLORA CORRELL THE COURIER-JOURNAL AND THE LOUISVILLE TIMES COVINGTON TRUST & BANKING COMPANY MR. AND MRS. GEORGE P. CROUNSE / GEORGE E. EVANS, JR. FARMERS BANK & CAPITAL TRUST COMPANY I FISHER-PRICE TOYS, MURRAY MARY PAULINE FOX, M.D., IN HONOR OF CHLOE GIFFORD MARY A. HALL, M.D., IN HONOR OF PAT LEE, JANICE HALL & AND MARY ANN FAULKNER OSCAR HORNSBY INC. / OFFICE PRODUCTS DIVISION IBM CORPORATION JERRY'S RESTAURANTS I ROBERT B. JEWELL LEE S. JONES I KENTUCKIANA GIRL SCOUT COUNCIL KENTUCKY BANKERS ASSOCIATION / KENTUCKY COAL ASSOCIATION, INC. -

Military History of Kentucky

THE AMERICAN GUIDE SERIES Military History of Kentucky CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED Written by Workers of the Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of Kentucky Sponsored by THE MILITARY DEPARTMENT OF KENTUCKY G. LEE McCLAIN, The Adjutant General Anna Virumque Cano - Virgil (I sing of arms and men) ILLUSTRATED Military History of Kentucky FIRST PUBLISHED IN JULY, 1939 WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION F. C. Harrington, Administrator Florence S. Kerr, Assistant Administrator Henry G. Alsberg, Director of The Federal Writers Project COPYRIGHT 1939 BY THE ADJUTANT GENERAL OF KENTUCKY PRINTED BY THE STATE JOURNAL FRANKFORT, KY. All rights are reserved, including the rights to reproduce this book a parts thereof in any form. ii Military History of Kentucky BRIG. GEN. G. LEE McCLAIN, KY. N. G. The Adjutant General iii Military History of Kentucky MAJOR JOSEPH M. KELLY, KY. N. G. Assistant Adjutant General, U.S. P. and D. O. iv Military History of Kentucky Foreword Frankfort, Kentucky, January 1, 1939. HIS EXCELLENCY, ALBERT BENJAMIN CHANDLER, Governor of Kentucky and Commander-in-Chief, Kentucky National Guard, Frankfort, Kentucky. SIR: I have the pleasure of submitting a report of the National Guard of Kentucky showing its origin, development and progress, chronologically arranged. This report is in the form of a history of the military units of Kentucky. The purpose of this Military History of Kentucky is to present a written record which always will be available to the people of Kentucky relating something of the accomplishments of Kentucky soldiers. It will be observed that from the time the first settlers came to our state, down to the present day, Kentucky soldiers have been ever ready to protect the lives, homes, and property of the citizens of the state with vigor and courage. -

ANZAC MOUNTED DIVISION Dividedinto Three Squadrons, Each of Six Troops, a Light Horse Regiment at War Establishment Is Made up of 25 Officers and 497 Men

CHAPTER V ANZAC MOUNTED DIVISION DIVIDEDinto three squadrons, each of six troops, a light horse regiment at war establishment is made up of 25 officers and 497 men. Of these, the Ist, and, and 3rd Brigades served complete upon Gallipoli, but the 4th Brigade was broken up upon arrival in Egypt. The 4th and 13th Regiments fought upon the Peninsula, but the 11th and 12th were disbanded, and were employed as reinforcements to other light horse units there. On their return to Egypt most of the regiments went direct from the transports to their horse-lines. There the men handed in their infantry packs, were given back their riding gear, and jingled very happily again in their spurs. During their absence in Gallipoli their horses had been to a large extent in the care of a body of public-spirited Aus- tralians, most of them well advanced in middle age, who, being refused as too old for active service, had enlisted and gone to Egypt as grooms in the light horsemen’s absence. Many of these men afterwards found employment in the remount dhpijts, and continued their useful service till the end of the war. All the regiments were much reduced in numbers, but the camps in Egypt then held abundant reinforcements, and a few weeks later eleven of the twelve regiments which after- wards served in Sinai and Palestine were at full strength. The 4th Regiment was reduced to two squadrons, one of which, together with the whole of the 13th Regiment, was sent as corps mounted troops to France, while the remaining squadron was for a time attached to an Imperial Service brigade doing special patrol duty against Turkish spies and agents upon the Egyptian side of the Canal.