Copyright 2012 Robert Henn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan the RADICAL CRITICISM OP GRANVILLE HICKS in the 1 9 3 0 *S

72 - 15,245 LONG, Terry Lester, 1936- THE RADICAL CRITICISM OF GRANVILLE HICKS IN THE 1930’S. The Ohio State University in Cooperation with Miami (Ohio) University, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THE RADICAL CRITICISM OP GRANVILLE HICKS IN THE 1 9 3 0 *S DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Terry L. Long, B. A. , M. A. Ohe Ohio State University 1971 Approved by A d v iser Department of English PLEASE NOTE: Some pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Hicks and the 1930*s ....................................... 1 II. Granville Hicks: Liberal, 1927-1932 .... 31 III. Granville Hicks: Marxist, 1932-1939 .... 66 IV. Hicks on the Marxian Method................... 121 V. Hicks as a Marxian A nalyst ........................ 157 V I. The B reak With Communism and A f t e r ..... 233 VII. Hicks and Marxist Criticism in Perspective . 258 BIBLIOGRAPHY......................................................................................... 279 i i CHAPTER I HICKS AM5 THE 1930* s The world was aflame with troubles In the 1930fs. They were years of economic crisis, war, and political upheaval. America, as Tennessee Williams said, "... was matriculating in a school for the blind." They were years of bewilderment and frustration for the common man. For many American writers and thinkers, the events of the decade called for several changes from the twenties; a move to the political left, a concern for the misery of the masses, sympathy for the labor movement, support of the Communist Party, hope for Russia as a symbol of the future, fear and hatred of fascism. -

Mary Mccarthy and Vassar

Mary McCarthy and Vassar 1 Mary McCarthy and Vass ar An Exhibition Catalogue VASSAR COLLEGE LIBRARIES 2012 2 3 Mary McCarthy and Vass ar An Exhibition Catalogue VASSAR COLLEGE LIBRARIES 2012 2 3 CONTENTS Mary McCarthy and Vassar page 5 The Company We Keep: Mary McCarthy and the Mythic Essence of Vassar page 7 Checklist of the Exhibition page 15 All essays 2012 © the authors 4 5 Mary McCarthy and Vassar By RONALD PATKUS 2012 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Mary McCarthy, one of 20th century America’s foremost writers and critics. She was born on June 21, 1912 in Seattle, Washington, the first child and only daughter of Roy Winfield and Therese (“Tess”) Preston McCarthy. McCarthy and her three younger brothers (Kevin, Preston, and Sheridan) were orphaned in 1918, when both parents died in the influenza epidemic. For a time the children lived with their great-aunt and her husband, but then McCarthy moved back to Seattle to live with her maternal grandparents, while her brothers were sent to boarding school. This was a privileged environment, and McCarthy at- tended excellent schools. In 1929 she enrolled in the freshmen class at Vassar. No one could have known it at the time, but McCarthy’s arrival on cam- pus was the beginning of a long relationship between her and the college, even though there were ups and downs at certain points. While a student, McCarthy was busy, making friends with classmates, writing for several un- dergraduate publications, and taking part in plays and other activities. Her academic responsibilities did not suffer, and she graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1933. -

Limited Editions Club

g g OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. Oak Knoll Books is a member of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB — about 2,000 dealers in 22 countries) and the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA — over 450 dealers in the US). Their logos appear on all of our antiquarian catalogues and web pages. These logos mean that we guarantee accurate descriptions and customer satisfaction. Our founder, Bob Fleck, has long been a proponent of the ethical principles embodied by ILAB & the ABAA. He has taken a leadership role in both organizations and is a past president of both the ABAA and ILAB. We are located in the historic colonial town of New Castle (founded 1651), next to the Delaware River and have an open shop for visitors. -

Mary Mccarthy

Mary McCarthy: Manuscripts for in the Manuscript Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: McCarthy, Mary, 1912-1989 Title: Mary McCarthy, Manuscripts for The Group Dates: 1953-1964 Extent: 2 boxes, 1 galley folder (.63 linear feet) Abstract: The Ransom Center’s holdings for Mary McCarthy comprise her draft chapters, final manuscript, and galley proofs for the novel The Group . RLIN Record #: TXRC05-A10006 Language: English . Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchase, 1968 (R4493) Processed by: Bob Taylor, 2003 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center McCarthy, Mary, 1912-1989 Biographical Sketch Born in Seattle on June 21, 1912, Mary McCarthy was the eldest of four children born to Roy and Therese McCarthy. Orphaned upon their parents’ deaths in the flu epidemic of 1918, Mary and her brothers eventually found refuge with their maternal grandparents in Seattle. Following her graduation from Vassar College in 1933, McCarthy, intending to pursue a literary career, moved to New York City, where she soon attracted attention for her essays and dramatic criticism. In the late 1930s she began to write short stories, several of which served as the nucleus of her first novel, The Company She Keeps, published in 1942. As one of the major figures in contemporary American cultural and political thought, Mary McCarthy wrote widely in fiction( The Oasis, Cast a Cold Eye, The Groves of Academe ), theater criticism( Mary McCarthy’s Theatre Chronicles, 1937-1962 ), memoir( Memories of a Catholic Girlhood and How I Grew ), and broad-ranging commentary( Venice Observed and The Mask of State: Watergate Portraits ). -

History 600: Public Intellectuals in the US Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Office

Hannah Arendt W.E.B. DuBois Noam Chomsky History 600: Public Intellectuals in the U.S. Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Lecturer: Ronit Stahl Class Meetings: Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 M 11 a.m.-1 p.m. email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Room: Mosse Hum. 5257 Prof. RR’s Office Hours: R.S.’s Office Hours: T 3- M 9 a.m.-11a.m. 5 p.m. This course is designed for students interested in exploring the life of the mind in the twentieth-century United States. Specifically, we will examine the life of particular minds— intellectuals of different political, moral, and social persuasions and sensibilities, who have played prominent roles in American public life over the course of the last century. Despite the common conception of American culture as profoundly anti-intellectual, we will evaluate how professional thinkers and writers have indeed been forces in American society. Our aim is to investigate the contested meaning, role, and place of the intellectual in a democratic, capitalist culture. We will also examine the cultural conditions, academic and governmental institutions, and the media for the dissemination of ideas, which have both fostered and inhibited intellectual production and exchange. Roughly the first third of the semester will be devoted to reading studies in U.S. and comparative intellectual history, the sociology of knowledge, and critical social theory. In addition, students will explore the varieties of public intellectual life by becoming familiarized with a wide array of prominent American philosophers, political and social theorists, scientists, novelists, artists, and activists. -

Dr. Lionel Trilling Jefferson Lecturer the Blakelock Problem

Humanities New York City, a sheaf of rolled-up canvases under his arm, while Blakelock bargained; as often as not, they’d return to the same dealers with the same pic tures just before closing, Blakelock desperate and willing to accept almost anything for his work. He was a self-taught artist, born and raised in New York City, who headed west after graduation from what is now the City University of New York, sketch ing his way across the plains to the coast, returning by way of Mexico, Panama, and the West Indies. At first he painted pictures in the Hudson River style— romantically colored panoramas identifiable with the locales he had visited. But as the years passed, the children came, and fame, fortune or even a minimal income eluded him, Blakelock started building on canvas a world of his own: dark scenes, heavy with overarching trees Dr. Lionel Trilling brooding over moonlit waters, highly romantic Indian Jefferson Lecturer encampments that never were. Bright colors left his palette, the hues of night dominated. Dr. Lionel Trilling will deliver the first Jefferson Lec Blakelock did build up a modest following of col ture in the Humanities before a distinguished au lectors, but in the 1870’s and 1880’s, $30 to $50 was dience at the National Academy of Sciences Audi a decent price for a sizable painting by an unknown, torium, 2101 Constitution Avenue Northwest, Wash and his fees never caught up with his expenses. Only ington, D. C. on Wednesday, April 26 at eight once did light break through: in 1883, the Toledo o ’clock. -

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - the American Interest

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - The American Interest https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-... https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-merit-before-meritocracy/ WHAT ONCE WAS Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy PETER SKERRY The perambulating path of this son of humble Jewish immigrants into America’s intellectual and political elites points to how much we have overcome—and lost—over the past century. The death of Nathan Glazer in January, a month before his 96th birthday, has been rightly noted as the end of an era in American political and intellectual life. Nat Glazer was the last exemplar of what historian Christopher Lasch would refer to as a “social type”: the New York intellectuals, the sons and daughters of impoverished, almost exclusively Jewish immigrants who took advantage of the city’s public education system and then thrived in the cultural and political ferment that from the 1930’s into the 1960’s made New York the leading metropolis of the free world. As Glazer once noted, the Marxist polemics that he and his fellow students at City College engaged in afforded them unique insights into, and unanticipated opportunities to interpret, Soviet communism to the rest of America during the Cold War. Over time, postwar economic growth and political change resulted in the relative decline of New York and the emergence of Washington as the center of power and even glamor in American life. Nevertheless, Glazer and his fellow New York intellectuals, relocated either to major universities around the country or to Washington think tanks, continued to exert remarkable influence over both domestic and foreign affairs. -

The Representation of the First World War in the American Novel

The representation of the first world war in the American novel Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Doehler, James Harold, 1910- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 07:22:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553556 THE REPRESENTATION OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR IN THE AMERICAN NOVEL ■ . ■ v ' James Harold Doehler A Thesis aotsdited to the faculty of the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Co U e g e University of Arisom 1941 Director of Thesis e & a i m c > m J::-! - . V 3^ J , UF' Z" , r. •. TwiLgr-t. ' : fejCtm^L «••»«[?; ^ aJbtadE >1 *il *iv v I ; t. .•>#»>^ ii«;' .:r i»: s a * 3LXV>.Zj.. , 4 W i > l iie* L V W ?! df{t t*- * ? [ /?// TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ..... .......... < 1 II. NOVELS WRITTEN DURING THE WAR. 9 III. NOVELS WRITTEN DURING THE 1920*8 . 32 IV. DOS PASSOS, HEMINGWAY, AND CUMMINGS 60 V. NOVELS WRITTEN DURING THE 1930*8 . 85 VI. CONCLUSION ....................... 103 BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................... 106 l a y 4 7 7 CHAPIER I niiRODUcnoa The purpose of this work is to discover the attitudes toward the first World War which were revealed in the American novel from 1914 to 1941. -

Robert Johnson, Folk Revivalism, and Disremembering the American Past

The Green Fields of the Mind: Robert Johnson, Folk Revivalism, and Disremembering the American Past Blaine Quincy Waide A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Folklore Program, Department of American Studies Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: William Ferris Robert Cantwell Timothy Marr ©2009 Blaine Quincy Waide ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Blaine Quincy Waide: The Green Fields of the Mind: Robert Johnson, Folk Revivalism, and Disremembering the American Past (Under the direction of William Ferris) This thesis seeks to understand the phenomenon of folk revivalism as it occurred in America during several moments in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. More specifically, I examine how and why often marginalized southern vernacular musicians, especially Mississippi blues singer Robert Johnson, were celebrated during the folk revivals of the 1930s and 1960s as possessing something inherently American, and differentiate these periods of intense interest in the traditional music of the American South from the most recent example of revivalism early in the new millennium. In the process, I suggest the term “disremembering” to elucidate the ways in which the intent of some vernacular traditions, such as blues music, has often been redirected towards a different social or political purpose when communities with divergent needs in a stratified society have convened around a common interest in cultural practice. iii Table of Contents Chapter Introduction: Imagining America in an Iowa Cornfield and at a Mississippi Crossroads…………………………………………………………………………1 I. Discovering America in the Mouth of Jim Crow: Alan Lomax, Robert Johnson, and the Mississippi Paradox…………………………………...23 II. -

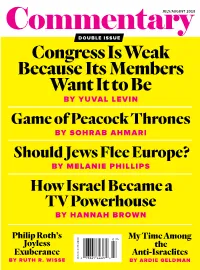

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

Lionel Trilling's Existential State

Lionel Trilling’s Existential State Michael Szalay Death is like justice is supposed to be. Ralph Ellison, Three Days Before the Shooting IN 1952, LIONEL TRILLING ANNOUNCED THAT “intellect has associated itself with power, per- haps as never before in history, and is now conceded to be in itself a kind of power.” He was de- scribing what would be his own associations: his personal papers are littered with missives from the stars of postwar politics. Senator James L. Buckley admires his contribution to American let- ters. Jacob J. Javits does the same. Daniel Patrick Moynihan praises him as “the nation’s leading literary critic.” First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy writes from the White House, thanking him for the collection of D. H. Lawrence stories and hoping to see him again soon. Three years later, President Lyndon Johnson sends a telegram asking Trilling to represent him at the funeral of T. S. Eliot. Politicians liked having Trilling around. He confirmed their noble sense of mission as often as they praised him.1 Trilling’s accommodating relation to power alienated many of his peers, like Irving Howe and C. Wright Mills, and later provoked condemnations from historians like Christopher Lasch and MICHAEL SZALAY teaches American literature and culture at UC, Irvine, and is the author of New Deal Modernism and The Hip Figure, forthcoming from Stanford University Press. He is co-editor of Stanford’s “Post*45” Book Series. 1 Trilling thought that the political establishment embraced intellectuals because it was “uneasy with itself” and eager “to apologize for its existence by a show of taste and sensitivity.” Trilling, “The Situation of the American Intellectual at the Present Time,” in The Moral Obligation to Be Intelligent, ed. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand.