Whose Urban Green? Mapping and Classifying Public and Private Green Spaces in Padua for Spatial Planning Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valori Agricoli Medi Della Provincia Annualità 2017

Ufficio del territorio di PADOVA Data: 07/11/2017 Ora: 11.08.36 Valori Agricoli Medi della provincia Annualità 2017 Dati Pronunciamento Commissione Provinciale Pubblicazione sul BUR n. del n. del REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 1 REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 2 COLLI EUGANEI PIANURA PADOVANA NORD/OCCIDENTALE Comuni di: ARQUA` PETRARCA, BAONE, BATTAGLIA TERME, CINTO Comuni di: CARMIGNANO DI BRENTA, CITTADELLA, FONTANIVA, EUGANEO, GALZIGNANO TERME, LOZZO ATESTINO, GALLIERA VENETA, GAZZO, GRANTORTO, SAN MARTINO DI MONTEGROTTO TERME, ROVOLON, TEOLO, TORREGLIA, VO` LUPARI, SAN PIETRO IN GU, TOMBOLO COLTURA Valore Sup. > Coltura più Informazioni aggiuntive Valore Sup. > Coltura più Informazioni aggiuntive Agricolo 5% redditizia Agricolo 5% redditizia (Euro/Ha) (Euro/Ha) BOSCO CEDUO (COMPRESE PIANTE) 13500,00 3-BOSCHI COME DEFINITI 13500,00 3-BOSCHI COME DEFINITI DALLA L.R. 13.09.78 N.52) DALLA L.R. 13.09.78 N.52) BOSCO MISTO (COMPRESE PIANTE) 15500,00 3-BOSCHI COME DEFINITI 15000,00 3-BOSCHI COME DEFINITI DALLA L.R. 13.09.78 N.52) DALLA L.R. 13.09.78 N.52) CASTAGNETO (DA PALATURA) 20500,00 FRUTTETO (COMPRESE PIANTE) 64000,00 1-SE DOTATI DI IMP.FISSO DI 67000,00 1-SE DOTATI DI IMP.FISSO DI IRRIG. E/O DRENAGGIO I IRRIG. E/O DRENAGGIO I VAL.VENGONO AUMENTATI VAL.VENGONO AUMENTATI DI 7000 EURO PER HA) DI 7000 EURO PER HA) 2-IN PRESENZA DI 2-IN PRESENZA DI IMPIANTO DI ACTINIDIA IMPIANTO DI ACTINIDIA INTENSIVO, SI APPLICA UNA INTENSIVO, SI APPLICA UNA MAGGIORAZIONE DEL 10%) MAGGIORAZIONE DEL 10%) INCOLTO (AREA NON PIÙ FUNZIONALE 13500,00 13500,00 AL SERVIZIO DEL FONDO) OLIVETO (COMPRESE PIANTE) 75000,00 ORTO 65000,00 1-SE DOTATI DI IMP.FISSO DI 70000,00 1-SE DOTATI DI IMP.FISSO DI IRRIG. -

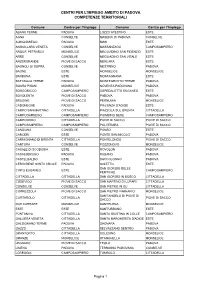

Centri Per L'impiego Ambito Di Padova Competenze Territoriali

CENTRI PER L'IMPIEGO AMBITO DI PADOVA COMPETENZE TERRITORIALI Comune Centro per l’Impiego Comune Centro per l’Impiego ABANO TERME PADOVA LOZZO ATESTINO ESTE AGNA CONSELVE MASERA' DI PADOVA CONSELVE ALBIGNASEGO PADOVA MASI ESTE ANGUILLARA VENETA CONSELVE MASSANZAGO CAMPOSAMPIERO ARQUA' PETRARCA MONSELICE MEGLIADINO SAN FIDENZIO ESTE ARRE CONSELVE MEGLIADINO SAN VITALE ESTE ARZERGRANDE PIOVE DI SACCO MERLARA ESTE BAGNOLI DI SOPRA CONSELVE MESTRINO PADOVA BAONE ESTE MONSELICE MONSELICE BARBONA ESTE MONTAGNANA ESTE BATTAGLIA TERME PADOVA MONTEGROTTO TERME PADOVA BOARA PISANI MONSELICE NOVENTA PADOVANA PADOVA BORGORICCO CAMPOSAMPIERO OSPEDALETTO EUGANEO ESTE BOVOLENTA PIOVE DI SACCO PADOVA PADOVA BRUGINE PIOVE DI SACCO PERNUMIA MONSELICE CADONEGHE PADOVA PIACENZA D'ADIGE ESTE CAMPO SAN MARTINO CITTADELLA PIAZZOLA SUL BRENTA CITTADELLA CAMPODARSEGO CAMPOSAMPIERO PIOMBINO DESE CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPODORO CITTADELLA PIOVE DI SACCO PIOVE DI SACCO CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPOSAMPIERO POLVERARA PIOVE DI SACCO CANDIANA CONSELVE PONSO ESTE CARCERI ESTE PONTE SAN NICOLO' PADOVA CARMIGNANO DI BRENTA CITTADELLA PONTELONGO PIOVE DI SACCO CARTURA CONSELVE POZZONOVO MONSELICE CASALE DI SCODOSIA ESTE ROVOLON PADOVA CASALSERUGO PADOVA RUBANO PADOVA CASTELBALDO ESTE SACCOLONGO PADOVA CERVARESE SANTA CROCE PADOVA SALETTO ESTE SAN GIORGIO DELLE CINTO EUGANEO ESTE CAMPOSAMPIERO PERTICHE CITTADELLA CITTADELLA SAN GIORGIO IN BOSCO CITTADELLA CODEVIGO PIOVE DI SACCO SAN MARTINO DI LUPARI CITTADELLA CONSELVE CONSELVE SAN PIETRO IN GU CITTADELLA CORREZZOLA PIOVE DI SACCO SAN PIETRO -

Padova-Piove Di Sacco-Correzzola-Cantarana

Linea - E002 - PADOVA-PIOVE DI SACCO-CORREZZOLA-CANTARANA Vettore Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Busitalia Cadenza fer fer fer fsc fVsc Sfns fsc fVsc Ssc fVsc fVns fVsc Sfns Note PP YH PADOVA AUTOSTAZIONE 10.45 . 12.25 12.40 13.15 13.15 . 14.10 14.10 17.45 17.45 18.30 18.30 PADOVA P.BOSCHETTI 10.48 . 12.28 12.43 13.18 13.18 . 14.13 14.13 17.48 17.48 18.33 18.33 PADOVA OSPEDALE 10.50 . 12.30 12.45 13.20 13.20 . 14.16 14.15 17.51 17.50 18.36 18.35 PADOVA PONTECORVO V.FACCIOLATI 10.53 . 12.33 12.48 13.23 13.23 . 14.20 14.18 17.55 17.53 18.40 18.38 PADOVA VOLTABAROZZO 11.00 . 12.40 12.55 13.30 13.30 . 14.28 14.25 18.06 18.00 18.51 18.45 RONCAGLIA 11.03 . 12.43 12.58 13.33 13.33 . 14.31 14.28 18.10 18.03 18.55 18.48 P.TE SAN NICOLO' 11.07 . 12.47 13.02 13.37 13.37 . 14.35 14.32 18.14 18.07 18.59 18.52 LEGNARO 11.11 . 12.51 13.06 13.41 13.41 . 14.39 14.36 18.18 18.11 19.03 18.56 VIGOROVEA 11.17 . 12.57 13.12 13.47 13.47 . 14.45 14.42 18.24 18.17 19.09 19.02 BV. BRUGINE 11.18 . -

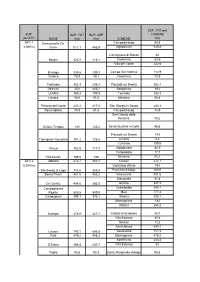

SUP. SUP. TOT Per COMUNE Per

SUP. TOT per SUP. SUP. TOT SUP. ASP COMUNE per ATC NOME (ha) (ha) COMUNE (ha) ATC 1Barrucchella Ca' Campodarsego 84,3 3.086 haFarini 611,1 456,9 Vigodarzere 526,8 Carmignano di Brenta 42 Boschi 125,9 115,1 Fontaniva 83,9 Villa del Conte 222,6 Busiago 335,5 299,3 Campo San Martino 112,9 Colonia 72,9 40,1 Fontaniva 72,9 Contarina 352,4 236,4 Piazzola sul Brenta 352,4 Desman 503 405,7 Borgoricco 503 La Mira 160,3 109,8 Tombolo 160,3 Lissaro 55,8 51,8 Mestrino 55,8 Palazzo del Conte 243,3 217,8 San Giorgio in Bosco 243,3 Reschigliano 74,5 61,8 Campodarsego 74,5 San Giorgio delle Pertiche 89,2 Guizze-Tergola 148 125,4 Santa Giustina in Colle 58,8 Piazzola sul Brenta 143 Tremignon Vaccarino 151,2 125,5 Limena 8,2 Curtarolo 109,6 Vanzo 142,5 117,3 Vigodarzere 32,9 Campodoro 17,7 Villa Kerian 109,8 106 Mestrino 92,1 ATC 2 Abbazia 272,7 252,1 Carceri 272,7 6.204 ha Vighizzolo d'Este 154 Barchessa al Lago 314,6 303,5 Piacenza d'Adige 160,6 Boara Pisani 481,6 463,2 Vescovana 481,6 Stanghella 57,4 Ca' Conti/2 404,6 383,5 Granze 347,2 Campagnazza Castelbaldo 348,1 Pajette 525,5 509,9 Masi 177,4 Campagnon 399,1 376,1 Urbana 399,1 Montagnana 182 Urbana 268,2 Grompe 478,9 427,1 Casale di Scodosia 28,7 Villa Estense 31,6 Granze 14,2 Sant'Urbano 540,1 Lavacci 743,1 696,8 Vescovana 157,2 Palù 475,2 448,3 Montagnana 475,2 Sant'Elena 233,4 S.Elena 298,4 287,7 Villa Estense 65 Taglie 95,8 93,3 Santa Margherita d'Adige 95,8 Tre Canne 218,4 216,8 Vighizzolo d'Este 218,4 Val Vecchia - Val Casale di Scodosia 348,8 Nuova 673 662,3 Merlara 324,2 Valli 202,8 197,3 -

Elenco Fattorie Didattiche in Provincia Di

PROVINCIA DI PADOVA PROVINCIA DI PADOVA NOTE AROMATICHE ALTAURA E MONTE CEVA Azienda agricola - Agriturismo Azienda agricola biologica - Agriturismo Albignasego Fattoria sociale www.sanpiox1708.it Casale di Scodosia www.scuolafattoria.it Azienda Agricola San Pio X 049 8010505 Agriturismo Altaura e Monte Ceva [email protected] 347 2500714 [email protected] CARESÀ Azienda agricola biologica - Agriturismo IL TRAMONTO Brugine Azienda agricola www.caresa.it Casalserugo Caresà Azienda agricola Il tramonto 348 7580206 348 2378167 [email protected] [email protected] IN PUNTA DI ZOCCOLI LA BUONA TERRA Azienda agricola Azienda agricola biologica - Agriturismo Brugine Cervarese Santa Croce www.inpuntadizoccoli.it www.buonaterrabio.it In punta di zoccoli Agriturismo Biologico La Buona Terra 329 7010828 328 0770977 [email protected] [email protected] APICOLTURA MIELE PIU' MONTE VENDA Azienda apistica Azienda agricola - Agriturismo Cartura Cinto Euganeo www.apicolturamielepiu.it www.agriturismoaltovenda.it Miele Più – Apicoltura Giarin Agriturismo Alto Venda 348 4752862 0429 647217 [email protected] [email protected] PROVINCIA DI PADOVA PROVINCIA DI PADOVA PODERE VILLA ALESSI OASI BETTELLA Azienda agricola - Agriturismo Azienda agricola biologica – Agriturismo Cinto Euganeo Limena www.villalessi.it Oasi Bettella Agriturismo Podere Villa Alessi 348 6048694 0429 634101 [email protected] [email protected] NATURIAMO LA REBOSOLA Azienda florovivaistica Azienda agricola - Agriturismo Massanzago Correzzola www.naturiamo.veneto.it -

Venerdi 3 Giugno Sabato 4 Giugno

Venerdi 3 giugno Sabato 4 giugno ore 19.00 Aperitivo In The Bottle DJ Set Ore 17.00 Apertura con In The Bottle DJ Set ore 20.00 Mangia come parli Ore 18.00 Concerto Bob Corn Reading ironico sulla cultura del cibo con Massimiliano Bruno, Lara Balbo, Gianni Ore 19.00 Corsi, Giulia Fiume, Maurizio Lops, Giuseppe Ragone, musiche di Fabio Antonelli Concerto The Giant Undertow Ore 20.00 Noir e gialli d’autore ore 21.00 Inaugurazione ufficiale del Festival con Fede&Tinto e Incontro con Massimo Polidoro, Giovanni Ricciardi e Paolo Roversi, presentazione del Contratto di Fiume a cura del Consorzio di Bonifica modera Leandro Barsotti Adige-Euganeo Ore 21.00 A tu per tu ore 21.30 Presentazione del libro Kitchen Social Club di Don Pasta Incontro con Massimiliano Bruno, modera Alberto Fassina ore 22.00 Cooking dj set con Don Pasta Ore 22.00 Nulla è andato perso - Gianni Maroccolo in concerto, con Un Dj set speziato di sonorità del mondo intero, tra il funk, il reggae, il Sud Antonio Aiazzi, Andrea Chimenti, Beppe Brotto e Simone Filippi America e la Londra meticcia, sul palco con vinili e pentole, mixer e minipimer Un emozionante concerto-spettacolo che ripercorre e racconta 30 anni di per frullare musica e veloutés. storia della musica, un viaggio nel viaggio: da Via de Bardi 32, la storica cantina fiorentina dei Litfiba dove tutto ebbe inizio fino a vdb23, l’ultimo lavoro Villa Correr ore 23.00 Concerto Contrada Lorì condiviso da Maroccolo con il compianto Claudio Rocchi. Casale di Scodosia Ore 00.00 Persinelparco Nel corso della serata spettacoli della Concerto Mr Wob & The Canes (Padova) compagnia di teatro di strada Fratelli Ochner Ore 01.00 Con la notte nel cuore - Racconti del Mistero con Giuliana Musso, Andrea Pennacchi, Mirko Artuso, musiche di Giorgio Gobbo e Sergio Marchesini. -

Deliberazione Del Direttore Generale

N. del DELIBERAZIONE DEL DIRETTORE GENERALE dott. Paolo FORTUNA Coadiuvato dai Signori: DIRETTORE AMMINISTRATIVO dr.ssa Michela Barbiero DIRETTORE SANITARIO dr. Aldo Mariotto DIRETTORE DEI SERVIZI SOCIO SANITARI dr.ssa Maria Chiara Corti Note Trasparenza: Si prende atto del Piano di Zona Straordinario anno 2021, armonizzato, del territorio dell’ULSS 6 Euganea, approvato dall’Esecutivo della Conferenza dei Sindaci il 25.02.2021 e che comprende il Piano di Zona straordinario dei Distretti Padova Bacchiglione - Terme Colli - Piovese, Alta Padovana, Padova Sud, approvati dai rispettivi Comitati dei Sindaci. OGGETTO: Presa d'atto del Piano di Zona Straordinario 2021- DGR n. 1252/2020. Il Dirigente della UOC Sociale, Daniela Salvato, riferisce: Il Piano di Zona è lo “strumento di programmazione delle politiche sociali e socio-sanitarie definite a livello locale in coerenza con le linee di indirizzo regionali” (DGRV 157/2010), di cui sono titolari i Comuni (L. 328/00, L.R. 56/1994 e smi, L.R.5/96, L.R. 11/2001 e smi, L.R. 19/2016). Le Linee Guida Regionali, approvate con DGRV n. 157 del 26.01.2010, avevano fissato in 5 anni la durata del Piano di Zona 2011-2015, prevedendo che annualmente si provvedesse al monitoraggio e alla ri-programmazione del documento, sottoposto a visto di congruità regionale in funzione della sua coerenza con gli indirizzi strategici. Comune di Galliera Veneta Prot. n. 0007509 del 30-06-2021 arrivo cat. 10 Cl. 1 Con successive DGRV 1841/2015, DGRV 2174/2016, DGRV 1974/2018, DGRV 2029/2019 e DGRV 1252 del 01.09.2020, la validità del Piano di Zona 2011-2015 è stata confermata fino al 28.02.2021. -

Torreglia: [email protected] Granze: [email protected]

F ORMATO EUROPEO PER IL CURRICULUM V I T A E INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome SBICEGO ROSITA Indirizzo c/o comune di Torreglia – Largo Marconi 1 – 35038 Torreglia (PD) c/o comune di Granze – via della libertà 247 – 35040 Granze (PD) Telefono Torreglia – 049/9930128 (centralino) Granze – 0429/98734 (centralino) Fax E-mail Torreglia: [email protected] Granze: [email protected] Nazionalità italiana Data di nascita 15/03/65 Stato famiglia Coniugata ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA • Date Dal 01/11/2017 in servizio a tempo indeterminato, a seguito di mobilità volontaria tra Enti, presso • Nome e indirizzo del datore di lavoro il comune di Torreglia (PD) in convenzione con il comune di Granze (PD), con funzioni di • Tipo di azienda o settore Responsabile Area Tecnica – Edilizia Privata e Lavori Pubblici – titolare di Posizione Organizzativa; • Tipo di impiego • Principali mansioni e responsabilità Dal 1/2/2017 al 31/10/2017 servizio in comando presso il comune di Bovolenta (PD) con funzione di Responsabile Area Tecnica – Settore Edilizia Privata Commercio Suap – titolare di Posizione Organizzativa; Dal 15/10/2015 al 6/11/2016 in servizio a tempo indeterminato, a seguito di mobilità volontaria tra Enti, Responsabile Area Tecnica – servizi Edilizia Privata, Suap, Urbanistica, Commercio, LLPP, Manutenzioni, Ecologia/Ambiente - del comune di Bolzano Vicentino (VI) – circa 6500 abitanti – con la qualifica di Istruttore Direttivo Tecnico – cat. D1/D4 – Titolare di Posizione Organizzativa e responsabile del procedimento per -

Ecco Qual È Il Gruppo Più Popoloso Della Provincia Di Padova

“Sei di… se”, ecco qual è il gruppo più popoloso della provincia di Padova (Fonte foto: corrierevicentino.it) Poco più di un anno fa scoppiava il boom dei “Sei di… se“, i gruppi Facebook nati per scambiare ricordi, vecchie foto e detti locali tra concittadini (o anche ex concittadini). Una volta esaurite le testimonianze del passato, molti di questi gruppi si sono evoluti, divenendo luoghi di confronto su tematiche attuali. Alcuni vietano la discussione politica, altri la favoriscono, divenendo teatro di dibattiti accesissimi. Ogni paese, anche il più piccolo, ha il suo. E i 104 Comuni della provincia di Padova non fanno eccezione. Estensione ha svolto una piccola ricerca, prendendo il numero di abitanti di ciascun paese (Fonte dati: Censimento generale del 2011) e rapportandolo al numero di membri di ciascun gruppo locale (Fonte dati: Facebook, relativi al 27 aprile 2015). In caso di più di un gruppo per Comune, è stato preso in considerazione il più “popoloso”. Obiettivo: valutare il senso di appartenenza – anche se solo per via “tecnologica” – dei cittadini al proprio paese. Com’era prevedibile, i gruppi con più utenti sono quelli delle cittadine con più abitanti: comanda ovviamente Padova con 9.109 membri, seguono Este (3.567), Abano Terme (3.379), Monselice (3.378), Albignasego (2.958), Cittadella (2.677), Montagnana (1.751), Conselve (1.500), Battaglia Terme (1.321) e Vigonza (1.253) a chiudere la top ten. I risultati sono invece sorprendenti per quanto riguarda il rapporto percentuale membri/abitanti: a guidare la classifica è Battaglia Terme, dove ben il 33,8% dei residenti è iscritto al gruppo del piccolo Comune termale. -

Piano Delle Acque Del Comune Di Borgo Veneto

Piano delle Acque di Borgo Veneto località di Megliadino San Fidenzio e Santa Margherita d’Adige Piano delle Acque del Comune di Borgo Veneto Località di Megliadino San Fidenzio e Santa Margherita d’Adige 20 Novembre 2019 Piano delle Acque di Borgo Veneto località di Megliadino San Fidenzio e Santa Margherita d’Adige Il Piano delle Acque Il Piano delle Acque strumento tecnico operativo finalizzato alla programmazione degli interventi per la mitigazione delle criticità idrauliche della rete idrografica minuta Piano delle Acque di Borgo Veneto località di Megliadino San Fidenzio e Santa Margherita d’Adige Obbiettivi Il Piano delle Acque si pone i seguenti obiettivi: • identificare nel territorio le differenti reti di deflusso delle acque, perimetrando i sottobacini. Lo studio non si limita alle acque pubbliche (meteoriche ed eventualmente miste), ma valuta anche la funzione di canali e fossi privati, nonché di fognature meteoriche o di tombinature a servizio di centri urbani; • ispezionare tali manufatti , rilevare le sezioni tipo esistenti e valutarne l’adeguatezza, individuando gli elementi (strozzature, ostruzioni, curve) che possono limitare la funzionalità della rete idraulica; • proporre interventi per la soluzione di criticità note o prevedibili connesse con l’insufficienza della rete analizzata, anche nel caso della rete minore e minuta priva di specifico ente gestore; Piano delle Acque di Borgo Veneto località di Megliadino San Fidenzio e Santa Margherita d’Adige Obbiettivi • individuare le competenze gestionali di ciascun canale, fosso o tratto di fognatura (p.e. Regione, Consorzio di bonifica, Provincia, Comune, altri enti o soggetti privati) e fissare modalità e frequenza di manutenzione delle opere; • redigere un regolamento di polizia idraulica e un prontuario di buone pratiche costruttive, che potrà valere da riferimento per le norme tecniche dei piani urbanistici comunali; • sviluppare elementi conoscitivi utili per azioni di protezione civile, in caso di eventi calamitosi. -

35043 Monselice (PD)

Via Albere, n. 30 - 35043 Monselice (PD) Comuni: Agna, Anguillara Veneta, Arquà Petrarca, Arre, Bagnoli di Sopra, Baone, Barbona, Battaglia Terme, Bovolenta, Candiana, Carceri, Cartura, Casale di Scodosia, Castelbaldo, Cinto Euganeo, Conselve, Due Car rare, Este, Galzignano Terme, Granze, Lozzo Atestino, Masi, Megliadino San Fidenzio, Megliadino San Vitale, Merlara, Monselice, Montagnana, Ospedaletto Euganeo, Pernumia, Piacenza D’Adige, Ponso, Pozzonovo, Saletto, San Pietro Viminario, Santa Margherita D ’Adige, Sant’Elena, Sant’Urbano, Solesino, Stanghella, Terrassa Padovana, Tribano, Urbana, Vescovana, Vighizzolo d’Este, Villa Estense, Vò DETERMINAZIONE DEL DIRETTORE AD INTERIM DELL'UNITA' OPERATIVA COMPLESSA GESTIONE DEL PERSONALE N. 69 DEL 09/05/2016 Oggetto: EVENTO FORMATIVO: "IL CODICE DI CONDOTTA PER LA PREVENZIONE ED IL CONTRASTO DEI COMPORTAMENTI MOLESTI E LESIVI DELLA DIGNITA' DELLE LAVORATRICI E LAVORATORI DELL'AZIENDA ULSS 17" IL DIRETTORE AD INTERIM DELL'UNITA' OPERATIVA COMPLESSA GESTIONE DEL PERSONALE Avv. Manuela Trivellin In esecuzione della deliberazione del Commissario n. 267 del 01 aprile 2016 ad oggetto: “Aggiornamento del sistema delle deleghe ai Dirigenti dei ruoli Amministrativo, Tecnico e Professionale”; Vista la deliberazione n. 1221 del 16/12/2015 con la quale è stato approvato il Piano Formativo Attuativo Annuale (PFAA) - anno 2016 – che comprende eventi formativi interni ed esterni, obbligatori, da perseguire entro l’anno 2016; Vista la richiesta del Presidente del Comitato Unico di Garanzia (CUG) dell’Azienda -

01 Elenco Località Comparti

ATER della Provincia di Padova Divisione comparti di intervento COMPARTO "A" COMPARTO "B" COMPARTO "C" COMPARTO "Comune di Padova" LEBAN Geom. Maurizio FRANCO Geom. Federico GAZZETTA Geom. Alberto DE ANGELI Geom. Thomas VIE DI PADOVA COMUNI DELLA PROVINCIA VIE DI PADOVA COMUNI DELLA PROVINCIA VIE DI PADOVA COMUNI DELLA PROVINCIA VIE DI PADOVA E PROVINCIA ASSAROTTI CADONEGHE BAJARDI AGNA ACQUETTE ABANO TERME ACQUETTE MARZOLO BEATO PELLEGRINO CAMPODARSEGO BARBARIGO ALBIGNASEGO AMBA ARADAM BATTAGLIA TERME ALEARDI A. MONTA' CABRINI CAMPOSAMPIERO BERTACCHI ANGUILLARA VENETA BENUSSI BARBONA ALTICHIERI DA ZEVIO MORANDINI CALABRESI CAMPO SAN MARTINO BONARDI ARRE BETTELLA BOARA PISANI ARMISTIZIO MORETTO DA BRESCIA CICONI CARMIGNANO DI BRENTA BOTTACIN ARZERGRANDE CADUTI RESISTENZA CASALE DI SCODOSIA ALZANO MORONI CITOLO DA PERUGIA CERVARESE S.CROCE BROFFERIO BAGNOLI DI SOPRA CANIZZARO CASTELBALDO BAJARDI NAPOLI (P.zza) COLONNELLO PICCIO CITTADELLA BRUNO GIORDANO BOVOLENTA CAVALIERI CINTO EUGANEO BATTISTI C. PASTORI (V.lo) COLLEGIO S.MARCO CURTAROLO CANTELE BRUGINE CERATO ESTE BEFFAGNA PASTRO C.SO MILANO FONTANIVA CARDAN CARTURA CIAMICIAN GRANZE BEZZECCA (C.te) PELLICO S. (ex GRAMSCI) DELLA SALUTARE GALLIERA VENETA CARO ANNIBALE CASALSERUGO CRIMEA MASI BOYLE PERUGINO (Del) DE' MENABUOI GAZZO PADOVANO CARRARO F.LLI CODEVIGO CROCE VERDE MEGLIADINO S.VITALE BORSO E BORGHETTO PILO R. DUPRE' GRANTORTO COLETTI CONSELVE CURIE MERLARA BOSCARDIN F.lli PINELLI FIORAZZO LIMENA CORRADINI CORREZZOLA DOTTESIO MONSELICE BRESSANONE PIOVESE FORNACE MORANDI LOZZO