Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coalition Politics: How the Cameron-Clegg Relationship Affects

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Bennister, M. and Heffernan, R. (2011) Cameron as Prime Minister: the intra- executive politics of Britain’s coalition. Parliamentary Affairs, 65 (4). pp. 778-801. ISSN 0031-2290. Link to official URL (if available): http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsr061 This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] Cameron as Prime Minister: The Intra-Executive Politics of Britain’s Coalition Government Mark Bennister Lecturer in Politics, Canterbury Christ Church University Email: [email protected] Richard Heffernan Reader in Government, The Open University Email: [email protected] Abstract Forming a coalition involves compromise, so a prime minister heading up a coalition government, even one as predominant a party leader as Cameron, should not be as powerful as a prime minister leading a single party government. Cameron has still to work with and through ministers from his own party, but has also to work with and through Liberal Democrat ministers; not least the Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg. The relationship between the prime minister and his deputy is unchartered territory for recent academic study of the British prime minister. This article explores how Cameron and Clegg operate within both Whitehall and Westminster: the cabinet arrangements; the prime minister’s patronage, advisory resources and more informal mechanisms. -

Title Protecting and Assisting Refugees and Asylum-Seekers in Malaysia

Title Protecting and assisting refugees and asylum-seekers in Malaysia : the role of the UNHCR, informal mechanisms, and the 'Humanitarian exception' Sub Title Author Lego, Jera Beah H. Publisher Global Center of Excellence Center of Governance for Civil Society, Keio University Publication year 2012 Jtitle Journal of political science and sociology No.17 (2012. 10) ,p.75- 99 Abstract This paper problematizes Malaysia's apparently contradictory policies – harsh immigration rules applied to refugees and asylum seekers on the one hand, and the continued presence and functioning of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on the other hand. It asks how it has been possible to protect and assist refugees and asylum seekers in light of such policies and how such protection and assistance is implemented, justified, and maintained. Giorgio Agamben's concept of the state of exception is employed in analyzing the possibility of refugee protection and assistance amidst an otherwise hostile immigration regime and in understanding the nature of juridical indeterminacy in which refugees and asylum seekers in Malaysia inhabit. I also argue that the exception for refugees in Malaysia is a particular kind of exception, that is, a 'humanitarian exception.' Insofar as the state of exception is decided on by the sovereign, in Carl Schmitt's famous formulation, I argue that it is precisely in the application of 'humanitarian exception' for refugees and asylum seekers that the Malaysian state is asserting its sovereignty. As for the protection and assistance to refugees and asylum seekers, it remains an exception to the rule. In other words, it is temporary, partial, and all together insufficient for the preservation of the dignity of refugees and asylum seekers. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Abai Sungai in Malaysia Acehnese in Malaysia Population: 1,500 Population: 86,000 World Popl: 1,500 World Popl: 4,093,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: Borneo-Kalimantan People Cluster: Aceh of Sumatra Main Language: Abai Sungai Main Language: Malay Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Unspecified Scripture: Complete Bible Source: WWF-Malaysia Caroline PANG www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Status Aceh - Pixabay "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Arab in Malaysia Bajau Bukit, Papar in Malaysia Population: 15,000 Population: 2,000 World Popl: 703,600 World Popl: 2,000 Total Countries: 31 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: Arab, Arabian People Cluster: Tukangbesi of Sulawesi Main Language: Arabic, North Levantine S Main Language: Malay Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 2.00% Chr Adherents: 0.20% Chr Adherents: 4.00% Scripture: Portions Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Pat Brasil Source: International Mission Board-SBC "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Bajau, West Coast in Malaysia Balinese in -

Lord Cecil Parkinson 1

Lord Cecil Parkinson 1 Trade minister in Margaret Thatcher's first government in 1979, Cecil Parkinson went on to become Conservative Party chairman. He was instrumental in privatizing Britain's state-owned enterprises, particularly electricity. In this interview, Parkinson discusses the rethink of the British Conservative Party in the 1970s, Margaret Thatcher's leadership in the Falklands War, the coal miners' strike, and the privatization of state-owned industries. Rethinking the Conservative Party, and the Role of Keith Joseph INTERVIEWER: Let's talk about Margaret Thatcher during the '70s. After the defeat of [Prime Minister Ted] Heath, Margaret Thatcher almost goes back to school. She and Keith Joseph go to Ralph Harris [at the Institute for Economic Affairs] and say, "Give us a reading list." What's going on here? What's Margaret really doing? LORD CECIL PARKINSON: I think Margaret was very happy with the Heath manifesto. If you look at the Heath manifesto, it was almost a mirror image of her 1979 manifesto. All the things—cutting back the role of the state, getting rid of the nationalized industries, curbing the train unions, cutting of taxes, controlling public expenditure—it's all there. It's a very, very good manifesto. And I've heard her recently compliment him on the 1970 manifesto, which was a slightly sort of backhanded compliment, really. What troubled her was that we could be bounced out of it. We could be moved from doing the things which we knew were right and doing things which we secretly knew were wrong because of circumstances, and I think instinctively she felt this was wrong, but she didn't have the sort of intellectual backup, she felt, to back up her instincts. -

Margaret Thatcher and Conservative Politics in England

Click Here to Rate This Resource MARGARET THATCHER AND CONSERVATIVE POLITICS IN ENGLAND Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia Nicknamed the “Iron Lady,” Margaret Thatcher (1925–2013) served longer than any other UK prime minister in the 20th century. IN A HISTORIC ELECTION IN 1979, VOTERS The Conservative Party, also cation secretary, part of his Cabinet IN THE UNITED KINGDOM (UK) ELECTED called the Tory Party, is one of two (government officials in charge of de- MARGARET THATCHER TO BE PRIME MIN- major parties in England along with partments). As secretary, she made a ISTER. SHE WAS THE FIRST WOMAN the more liberal-left Labour Party (in controversial decision to end the gov- ELECTED TO THAT OFFICE. SHE WENT ON the UK, the word “labor“ is spelled ernment’s distribution of free milk to TO BE THE LONGEST-SERVING PRIME labour). Conservatism is a political schoolchildren aged 7 to 11. The press MINISTER IN THE 20TH CENTURY. AS ideology that generally supports pri- revealed that she privately opposed HEAD OF THE UK GOVERNMENT AND vate property rights, a limited govern- ending the free-milk policy, but the LEADER OF THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY, ment, a strong national defense, and Treasury Department had pressured THATCHER PROVOKED CONTROVERSY. EVEN AFTER HER DEATH IN 2013, SHE the importance of tradition in society. her to cut government spending. REMAINS A HERO TO SOME AND A The Labour Party grew out of the VILLAIN TO OTHERS. trade union movement in the 19th ‘Who Governs Britain?’ century, and it traditionally supports Struggles between the UK govern- Born in 1925, Thatcher was the the interests of working people, who ment and trade unions marked daughter of Alfred Roberts, a middle- want better wages, working condi- Thatcher’s career. -

Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a paper published in Political Quarterly White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/78536 Paper: Theakston, K and Gill, M (2011) The Postwar Premiership League. Political Quarterly, 82 (1). 67 - 80. ISSN 0032-3179 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2011.02170.x White Rose Research Online [email protected] The Post-war Premiership League Kevin Theakston and Mark Gill Who has been the best British prime minister since the Second World War? As David Cameron passes up and down the Grand Staircase in Number 10 Downing Street every day, the portraits of his predecessors as prime minister stare down at him. They are arranged in chronological order, with the most recent at the top of the stairs. If they were to be arranged in order of greatness, success or effectiveness in office, or policy achievement and legacy, the sequence would look very different. We report here the results from the latest survey of academic experts polled on the performance of post-1945 prime ministers. Academic specialists in British politics and history rate Clement Attlee as the best post-war prime minister, with Margaret Thatcher in second place just ahead of Tony Blair in third place. Gordon Brown’s stint in Number 10 was the third- worst since the Second World War, according to the respondents to the survey that rated his premiership as less successful than that of John Major. -

Distribution and Demography of the Orang Asli in Malaysia

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 6 Issue 1||January. 2017 || PP.40-45 Distribution and Demography of the Orang Asli in Malaysia Tuan Pah Rokiah SyedHussain1, Devamany S. Krishnasamy2, Asan Ali Golam Hassan3 1(School of Government,College of Law,Government and International Studies,Universiti Utara Malaysia) 2(School of Government,College of Law,Government and International Studies,Universiti Utara Malaysia) 3(Department, College/ University Name, Country NaInternational Business School, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia) ABSTRACT: This article discusses the Orang Asli demography found in various parts of Malaysia. The importance of this article relates to the knowledge context of Orang Asli as a minority who are still backward with regards to their unique distribution and demographic profile as compared to the Malay or other communities in the urban areas. They live in deep interior rural areas and are far away from modernization. As such, articles on this community become paramount to create awareness amongst people on their existence and challenges Keywords: Demography of Orang Asli, Distribution of Orang Asli, Minority Ethnic, Orang Asli I. INTRODUCTION The Orang Asli (OA) are called by various names, depending on the characteristics of the livelihood of the OA concerned. According to him (at that time), the aboriginal tribes have no proper native name on their own and therefore suitable designations have had to be found. According to him too, the other name for the OA that is recorded in the literature is Kensiu. At that time, the Malays referred to the OA by many names, like Orang Utan (jungle men), to differentiate them from the Malays who were called Village Dwellers [1]. -

The Fall of the Attlee Government, 1951

This is a repository copy of The fall of the Attlee Government, 1951. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85710/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Crowcroft, R and Theakston, K (2013) The fall of the Attlee Government, 1951. In: Heppell, T and Theakston, K, (eds.) How Labour Governments Fall: From Ramsay Macdonald to Gordon Brown. Palgrave Macmillan , Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire , pp. 61-82. ISBN 978-0-230-36180-5 https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137314215_4 © 2013 Robert Crowcroft and Kevin Theakston. This extract is taken from the author's original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: dx.doi.org/10.1057/9781137314215_4. Reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

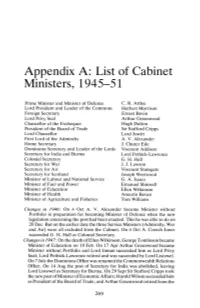

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office. -

Malay Minorities in the Tenasserim Coast

ASEAN Journal of Community Engagement Volume 4 Number 1 July Article 12 7-31-2020 Malay minorities in The Tenasserim coast Ma Tin Cho Mar Department of South East Asian Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, [email protected] Pham Huong Trang International School, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/ajce Part of the Polynesian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mar, Ma Tin Cho and Trang, Pham Huong (2020). Malay minorities in The Tenasserim coast. ASEAN Journal of Community Engagement, 4(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.7454/ajce.v4i1.1069 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. This Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Universitas Indonesia at ASEAN Journal of Community Engagement. It has been accepted for inclusion in ASEAN Journal of Community Engagement. Ma Tin Cho Mar, Pham Huong Trang | ASEAN Journal of Community Engagement | Volume 4, Number 1, 2020 Malay minorities in The Tenasserim coast Ma Tin Cho Mara*, Pham Huong Trangb aDepartment of South East Asian Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia bInternational School, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam Received: December 29th, 2019 || Revised: January 30th, 2020 || Accepted: July 29th, 2020 Abstract This paper discusses the Malay Minorities of the Malay Minorities in the Tenasserim Coast. And Tanintharyi Division is an administrative region of Myanmar at present. When we look closely at some of the interesting historical facts, we see that this region is “Tanao Si” in Thai, or Tanah Sari in Malay. -

The Rise of the Novice Cabinet Minister?

The Rise of the Novice Cabinet Minister? The Career Trajectories of Cabinet Ministers in British Government from Attlee to Cameron Some commentators have observed that today’s Cabinet ministers are younger and less experienced than their predecessors. To test this claim, we analyse the data for Labour and Conservative appointments to Cabinet since 1945. Although we find some evidence of a decline in average age and prior experience, it is less pronounced than for the party leaders. We then examine the data for junior ministerial appointments, which reveals that there is no trend towards youth and inexperience present lower down the hierarchy. Taking these findings together, we propose that public profile is correlated with ‘noviceness’; that is, the more prominent the role, the younger and less experienced its incumbent is likely to be. If this is correct, then the claim that we are witnessing the rise of the novice Cabinet minister is more a consequence of the personalisation of politics than evidence of an emerging ‘cult of youth’. Keywords: Cabinet ministers; junior ministers; party leaders; ministerial selection; personalisation; symbolic leadership Introduction In a recent article, Philip Cowley identified the rise of the novice political leader as a ‘major development’ in British politics. Noting the youth and parliamentary inexperience of David 1 Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg at the point at which they acquired the leadership of their parties, Cowley concluded that: ‘the British now prefer their leaders younger than they used to [and] that this is evidence of some developing cult of youth in British politics’, with the desire for younger candidates inevitably meaning that they are less experienced. -

Coalition Government Has Created a New Balance of Power at the Centre of UK Government (But That Shouldn’T Be a Surprise)

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/2010/08/17/coalition-government-has-created-a-new-balance- of-power-at-the-centre-of-uk-government-but-that-shouldn%e2%80%99t-be-a-surprise/ Coalition government has created a new balance of power at the centre of UK government (but that shouldn’t be a surprise) Passing the first 100 days mark suggests to Andrew Blick and George Jones that the coalition government has begun to revive some earlier historical precedents in Cabinet government. Unlike his immediate predecessors, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair, because of the inclusion of Liberal Democrats ministers David Cameron has had to share power and work closely with his cabinet and the Deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg, with major consequences for the role of 10 Downing Street. The Prime Minister as a post has always been filled by one person, but the premiership as an institution has always been exercised by a group. Its fundamental role is to provide public leadership, which involves (a) giving strategic direction (setting the tone of government) and (b) making urgent responses to events, responses that other institutions and procedures on their own cannot, and giving government a public face. Alterations in how these roles are allocated have tended to reflect two patterns of changes at No.10: ‘zigzags’ and ‘institutional fusions and fissions’. ‘Zigzags’ are radical changes of style in the way the premiership operates following a handover from one Prime Minister to another, especially a transition from a more to a less domineering premier, or vice versa.