The Educational Leadership Experiences of Jesuit Directors Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juan Pablo II a Los Sacerdotes John Paul II to Priests

Cuadernos de Pensamiento Nº 33 Número monográfico sobre Karol Wojtyla/san Juan Pablo II en el centenario de su nacimiento. Volumen 2. Año: 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.51743/cpe.65 Juan Pablo II a los sacerdotes John Paul II to priests MIGUEL FERNANDO GARCÍA Universidad Eclesiástica San Dámaso RESUMEN: El autor desarrolla el artículo en forma de díptico: en primer lugar, se ocupa de la teología y la espiritualidad sacerdotal de Juan Pablo II, vista a lo largo de su itinerario magisterial característico; en un segundo momento, expone, a modo de síntesis, la pastoral sacerdotal que nos ofrece san Juan Pablo II. Salva la distancia entre la realidad ontoteológica y su desenvolvimiento moral a través de una exhortación apremiante a la santidad de vida en la caridad pastoral. PALABRAS CLAVE: sacerdocio, don, misterio, eucaristía, caridad pastoral ABSTRACT: The author develops this paper in the form of a diptych. Firstly, he deals with the theology and priestly spirituality of John Paul II, seen throughout his char- acteristic magisterial journey. In a second moment, the author exposes, by way of synthesis, the priestly ministry that Saint John Paul II offers us. This bridges the gap between ontotheological reality and its moral development through a compelling exhortation to sanctity of life in pastoral charity. KEYWORDS: priesthood, gift, mystery, Eucharist, pastoral charity ISSN 02140284 Cuadernos de pensamiento 33 (2020): pp. 151-194 152 MIGUEL FERNANDO GARCÍA gradezco la oportunidad que me ofrece la Fundación Universitaria A Española para reflexionar sobre la exposición que san Juan Pablo II realizó sobre el sacerdocio a lo largo de su pontificado. -

Bibliography on the History of the Jesuits : Publications in English

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/bibliographyonhi281begh . H nV3F mm Ǥffi fitwffii 1 unBK i$3SOul nt^ni^1 ^H* an I A'. I ' K&lfi HP HHBHHH b^SHs - HHHH hHFJISi i *^' i MPiUHraHHHN_ ^ 4H * ir Til inrlWfif O'NEILL UBRAHJ BOSTON COLLEGE Bibliography on the History of the \ Jesuits Publications in English, 1900-1993 Paul Begheyn, S.J. CD TtJ 28/1 JANUARY 1996 ft THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recom- mendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar wel- comes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclu- sively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR George M. Anderson, S.J., is associate editor of America, in New York, and writes regularly on social issues and the faith (1993). Peter D. Byrne, S.J., is rector and president of St. -

Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 4-2018 Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit Charism and Students' Moral Judgement Scott weS nson University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons Recommended Citation Swenson, Scott, "Exploring the Relationship Between Students' Perceptions of the Jesuit Charism and Students' Moral Judgement" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 453. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/453 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STUDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS OF THE JESUIT CHARISM AND STUDENTS’ MORAL JUDGEMENT A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of Leadership Studies Catholic Educational Leadership Program In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Scott Swenson San Francisco April 2018 ABSTRACT Jesuit education has long focused on developing leaders of conscience, competence, and compassion. There is a gap in the literature examining if aspects of the Jesuit charism influence moral development. The Ignatian Identity Survey (IGNIS), and the Defining Issues Test – 2 (DIT-2), were administered to seniors at an all-male Jesuit high school. -

Pope John Paul II Shepherd for the Church and the World 1920-2005 Pope John Paul II Was Voice of Conscience for World, Modern-Day Apostle

20-PAGE SPECIAL ISSUE CCATHOLICATHOLIC Serving the People of the new york Archdiocese of New York newApril 2005 Volume XXIV, No. 7 york $1.00 Pope John Paul II Shepherd for the Church And the World 1920-2005 Pope John Paul II Was Voice of Conscience for World, Modern-Day Apostle By JOHN THAVIS cheered by millions. Pope John Paul’s personality was powerful and complicated. In his prime, he could work a crowd ope John Paul II, who died April 2 at age 84, was and banter with young and old, but spontaneity was Pa voice of conscience for the world and a not his specialty. As a manager, he set directions but modern-day apostle for his Church. often left policy details to top aides. To both roles he brought a philosopher’s intellect, a His reaction to the mushrooming clerical sex abuse pilgrim’s spiritual intensity and an actor’s flair for the scandal in the United States in 2001-02 underscored dramatic. That combination made him one of the his governing style: He suffered deeply, prayed at most forceful moral leaders of the modern age. length and made brief but forceful statements empha- As head of the Church for more than 26 years, he sizing the gravity of such a sin by priests. He con- held a hard line on doctrinal issues and drew sharp vened a Vatican-U.S. summit to address the problem, limits on dissent—in particular regarding abortion, but let his Vatican advisers and U.S. Church leaders birth control and other contested Church teachings work out the answers. -

Fall 2016 Issue 45

Fall 2016 Issue 45 Unpacking the ‘soul-sickness’ of racism… Featured Articles Shootings in Texas, Minnesota and Louisiana raise need for engagement, conversation, conversion Gretchen R. Crowe, OSV Newsweekly Unpacking the Soul-sickness of Racism In the aftermath of a Our Journey Continues… turbulent week that saw the Guidelines for Building unprovoked shooting of two Intercultural Competence unarmed black men by white for Ministers police officers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Words of Wisdom: What Minneapolis, followed by We Have Seen and Heard the shocking assassination of five uniformed officers in Building Intercultural Dallas by a black man, many Competence Father Bryan Massingale, professor of theological leaders — including those in the Church — have called Celebrating Diversity: Asian and ethics at Fordham University, speaks Nov. 6 in New Orleans. CNS photo/Peter Finney Jr., for a national conversation Pacific Island Catholic Day of Clarion Herald around the topic of race. Reflection In a statement July 8th, Archbishop Joseph E. Kurtz, president of the Understanding Culture U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, called all citizens to a “national reflection.” Multicultural Communication Obstacles to Intercultural “In the days ahead, we will look toward additional ways of nurturing an Relations open, honest and civil dialogue on issues of race relations, restorative justice, mental health, economic opportunity, and addressing the A Vision for Building Intercul- question of pervasive gun violence,” he said. tural Competence In Dallas, Bishop Kevin J. Farrell also called for dialogue. Society of St. Vincent de Paul Collaborates with IAACEC “We cannot lose respect for each other, and we call upon all of our civic Attendees in Louisville leaders to speak to one another and work together to come to a sensible resolution to this escalating violence,” he wrote on his blog July 8th. -

Ignatius, Faber, Xavier:. Welcoming the Gift, Urging

IGNATIUS, FABER, XAVIER:. WELCOMING THE GIFT, Jesuit working group URGING THE MISSION Provinces of Spain “To reach the same point as the earlier ones, or to go farther in our Lord” Const. 81 ent of 1539 was approaching. Ignatius and the first companions know that in putting themselves at the Ldisposition of the Pope, thus fulfilling the vow of Montmartre, the foreseeable apostolic dispersion will put an end to “what God had done with them.” What had God done in them, and why don’t they wish to see it undone? Two lived experiences precede the foundation of the Society which will shape the most intimate desire of the first companions, of their mission and their way of proceeding: the experience of being the experience of being “friends “friends in the Lord” in the Lord” and their way of and their way of helping others by helping others by living and living and preaching preaching “a la apostólica” “a la apostólica” (like (like apostles) apostles). The first expression belongs to St. Ignatius: “Nine of my friends in the Lord have arrived from Paris,” he writes to his friend Juan de Verdolay from Venice in 1537. To what experience of friendship does Ignatius allude? Without a doubt it refers to a human friendship, born of closeness and mutual support, of concern and care for one another, of profound spiritual communication… It also signifies a friendship that roots all its human potential in the Lord as its Source. It is He who has called them freely and personally. He it is who has joined them together as a group and who desires to send NUMBER 112 - Review of Ignatian Spirituality 11 WELCOMING THE GIFT - URGING THE MISSION them out on mission. -

Descargar Descargar

ARCHIVO HISTÓRICO El presente artículo corresponde a un archivo originalmente publicado en Ars Medica, revista de estudios médicos humanísticos, actualmente incluido en el historial de Ars Medica Revista de ciencias médicas. El contenido del presente artículo, no necesariamente representa la actual línea editorial. Para mayor información visitar el siguiente vínculo: http://www.arsmedica.cl/index.php/MED/about/su bmissions#authorGuidelines La contribución de la Iglesia Católica al desarrollo de la Bioética Monseñor Elio Sgreccia Ex Presidente de la Pontificia Academia Pro Vita Vaticano Resumen En este artículo se muestra que la Iglesia Católica ha hecho importantes aportes al desarrollo de la Bioética, tanto en sus orígenes históricos como en la reflexión sobre algunos temas y contenidos particulares. Desde el punto de vista histórico, se menciona la creación de algunas instituciones y organismos que han contribuido al desarrollo de una bioética católica; desde la perspectiva de los temas y contenidos, se propone que el aporte específico de la Iglesia Católica al desarrollo de la bioética comprende cuestiones de método, de epistemología y de fundamentación. En este contexto se mencionan algunos documentos del Magisterio eclesiástico que han contribuido a iluminar y enriquecer la reflexión bioética sobre algunos temas concretos. Central a este aporte de la Iglesia es la comprensión de la persona y su dignidad, especialmente a partir del Concilio Vaticano II, que desarrolla un “personalismo critológico”. Particularmente relevante ha sido, en este mismo sentido, la contribución de Juan Pablo II a través de sus escritos publicados antes y durante su Pontificado. palabras clave: bioética; personalismo; Iglesia Católica; personalismo cristológico. CONTRIBUTION OF CATHOLIC CHURCH TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF BIOETHICS This article shows that the Catholic Church has made important contributions to the development of Bioethics, both in its historic origins, as well as in the reflection on particular topics and contents. -

Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back

00621_conversations #26 12/13/13 5:37 PM Page 5 A Remnant and Rebirth Pope Pius VII Brings the Jesuits Back By Thomas W. Worcester, S.J. n 2013, for the first time ever, a Jesuit was elected than ten years from entrance as a novice to ordination as a pope. Although this was a first and a surprise, the priest, and then still longer until final vows, the definitive Society of Jesus has always depended on the papa- incorporation of an individual into the Society. But there had cy for its very existence, just as popes have depend- sometimes been diocesan priests who entered, and their for- ed on Jesuits as teachers, scholars, writers, preach- mation would be shorter, allowing them to take up full-time ers, spiritual directors, and missionaries and for work as Jesuits relatively quickly. This also happened in many other roles. Pope Paul III approved the 1814 and beyond. An example is Francesco Finetti Society of Jesus on September 27, 1540; Clement (1762–1842), a well-known Italian preacher who entered the XIV suppressed it on July 21, 1773; Pius VII restored Jesuits in autumn of 1814. He continued his preaching min- it on August 7, 1814. For two centuries no pope has istry as a Jesuit, and among his published works is a sermon reversed Pius VII’s decision, though certain popes, annoyed or he preached in Rome in August 1815 on the theme of St. angered by individual Jesuits or by the Society of Jesus as a Peter in Chains: he compared Pius VII to Peter, and whole, may have given such action some or maybe even a lot Napoleon to the pagan Roman emperors; providence had of thought. -

Are Informationes Ethical?

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/areinformationes294keen IN THE SPIRITUALITY OF JESUITS Are Informationes Ethical? James F. Keenan, S J. 29/4 • SEPTEMBER 1997 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recom- mendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar wel- comes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclu- sively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Richard J. Clifford, S.J., teaches Old Testament at Weston Jesuit School of Theology in Cambridge, Mass. (1997). Gerald M. Fagin, S.J., teaches theology in the Institute for Ministry at Loyola University, New Orleans, La. (1997). Gerald P. Fogarty, S.J., teaches history in the department of religious studies at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va. (1995). John P. Langan, S.J., as holder of the Kennedy Chair of Christian Ethics, teach- es philosophy at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. -

Jesuit Formation Today: an Invitation to Dialogue and Involvement

STUDIES IN THE SPIRITUALITY OF JESUITS mwk Jesuit Formation Today: An Invitation To Dialogue and Involvement William A. Barry, S.J. NOVEMBER 1988 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recommendation to religious institutes to recapture the original inspiration of their founders and to adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar welcomes reactions or comments in regard to the material which it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, laity, men and/or women. Hence the Studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclusively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR L. Patrick Carroll, S.J., is pastor of St. Leo's Parish in Tacoma, Washington and superior of the Jesuit community there. John A. Coleman, S.J., teaches Christian social ethics at the Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley. Robert N. Doran, S.J., is one of the editors of the complete works of Bernard Lonergan and teacher of systematic theology at Regis College, the Jesuit School of Theology in Toronto. Philip C. Fischer, S.J., is secretary of the Seminar and an editor at the Institute of Jesuit Sources. -

Angelus Cover (Page 1)

West Texas Read Pope Benedict XVI’s ANGELUSANGELUS First Papal Letter to the Serving the Diocese of San Angelo, Texas Catholic faithful/6 Volume XXVI, No. 6 JUNE 2005 Sainthood process on fast track for John Paul II Pope Benedict XVI speeds up efforts to appreciable amount of expediency, but the “fast track” designation bring sainthood to his internationally beloved time, and Krakow, does move that process in the right direction. predeccesor. Poland, Cardinal “The fastest track I know of comes from Franciszek Macharski the Holy Spirit,” said Michael Pfeifer, Bishop By Jimmy Patterson said Pope John Paul II’s of the Diocese of San Angelo. “John Paul II Editor West Texas Angelus cause would “fulfill all was a great leader and did so much for the Welcome ... requirements like any church. He cooperated in a unique manner other sainthood cause.” with the grace that was offered him as a man ... to the new Angelus. We hope you The cause to put on a fast track the beatifi- Simply because Pope and a Christian.” find the changes we’re introducing to cation of Pope John Paul II is news that is not John Paul’s stature the Pope John Paul II’s Two miracles must be attributed to a poten- your liking. entirely unexpected because of the late pon- world over was sainthood cause to be tial saint and those miracles must occur after The Catholic Church is about many tiff’s holiness, according to Cardinal Jose renowned and he was put on fast track. death. things. Guiding its people in the way of Saraiva Martins, who spoke last month on so beloved by Catholics Christ and in the teachings of the church Vatican radio. -

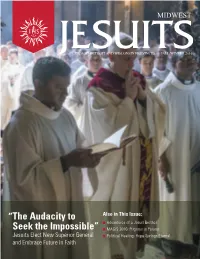

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr.