Colonized and Racist Indigenous Campus Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNM Campus Map.Pdf

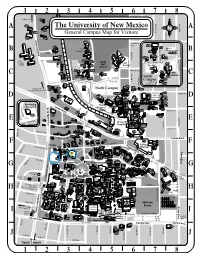

12345678 to Bldg. 259 277 Girard Blvd. Princeton Dr. A 278 The University of New Mexico A 255 N 278A General Campus Map for Visitors Vassar Dr. 271 265 University Blvd. 260 Constitution Ave. 339 217 332 Married Casa University Blvd. Student Housing B Esperanza Stanford Dr. 333 B KNME-TV 317-329 270 262 337 218 334 331 Buena Vista Dr. Carrie 240 243 Tingley 272 North Law Avenida De Cesar Chavez Golf 301 Hospital 233 241 239 School “The Pit” Camino de Salud Course 302 237 236B 230 Mountain Rd. 312 307 C 223 Stanford Dr. UNM C 206 Stadium 205 242 Columbia Dr. South 308 238 236A Campus 311 Tucker Rd. Tucker Rd. to South Golf Course 311A C 216 a 276 m 208 210 221 to Bldg. 259 252 in North Campus 219 o 263 1634 University Blvd. NE d e 251 S a 213-215 209 231 Marble Ave. lu Yale Blvd. Bernalillo Cty. D 250 d 249 D Mental Health 246 273 204 248 234 266 Center 225 268 258 Continuing Health 228 U 253 247 n Education Lomas Blvd. i Sciences 229 v 211 e 226 r Center 212 s 264 Frontier Ave. i t y 220 201 B l v 203 d 259 183 . 227 232 Girard Blvd. E N. Yale Entrance E 175 202 Vassar Dr. Mesa Vista Rd. 207 University Indian School Rd. Hospital University Blvd. University Mesa Vista Rd. 235 Revere Pl. 182 224 Sigma Chi Rd. 165 154 256 269 171 Spruce St. 191 151 Si d. Yale Blvd. -

University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN EAU CLAIRE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION Study Abroad UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW, GLASGOW, SCOTLAND 2020 Program Guide ABLE OF ONTENTS Sexual Harassment and “Lad Culture” in the T C UK ...................................................................... 12 Academics .............................................................. 5 Emergency Contacts ...................................... 13 Pre-departure Planning ..................................... 5 911 Equivalent in the UK ............................... 13 Graduate Courses ............................................. 5 Marijuana and other Illegal Drugs ................ 13 Credits and Course Load .................................. 5 Required Documents .......................................... 14 Registration at Glasgow .................................... 5 Visa ................................................................... 14 Class Attendance ............................................... 5 Why Can’t I fly through Ireland? ................... 14 Grades ................................................................. 6 Visas for Travel to Other Countries .............. 14 Glasgow & UWEC Transcripts ......................... 6 Packing Tips ........................................................ 14 UK Academic System ....................................... 6 Weather ............................................................ 14 Semester Students Service-Learning ............. 9 Clothing............................................................ -

Albuquerque Tricentennial

Albuquerque Tricentennial Fourth Grade Teachers Resource Guide September 2005 I certify to the king, our lord, and to the most excellent señor viceroy: That I founded a villa on the banks and in the valley of the Rio del Norte in a good place as regards land, water, pasture, and firewood. I gave it as patron saint the glorious apostle of the Indies, San Francisco Xavier, and called and named it the villa of Alburquerque. -- Don Francisco Cuervo y Valdes, April 23, 1706 Resource Guide is available from www.albuquerque300.org Table of Contents 1. Albuquerque Geology 1 Lesson Plans 4 2. First People 22 Lesson Plan 26 3. Founding of Albuquerque 36 Lesson Plans 41 4. Hispanic Life 47 Lesson Plans 54 5. Trade Routes 66 Lesson Plan 69 6. Land Grants 74 Lesson Plans 79 7. Civil War in Albuquerque 92 Lesson Plan 96 8. Coming of the Railroad 101 Lesson Plan 107 9. Education History 111 Lesson Plan 118 10. Legacy of Tuberculosis 121 Lesson Plan 124 11. Place Names in Albuquerque 128 Lesson Plan 134 12. Neighborhoods 139 Lesson Plan 1 145 13. Tapestry of Cultures 156 Lesson Plans 173 14. Architecture 194 Lesson Plans 201 15. History of Sports 211 Lesson Plan 216 16. Route 66 219 Lesson Plans 222 17. Kirtland Air Force Base 238 Lesson Plans 244 18. Sandia National Laboratories 256 Lesson Plan 260 19. Ballooning 269 Lesson Plans 275 My City of Mountains, River and Volcanoes Albuquerque Geology In the dawn of geologic history, about 150 million years ago, violent forces wrenched the earth’s unstable crust. -

Page 1 a B C D E F G H I J a B C D E F G H I J 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6

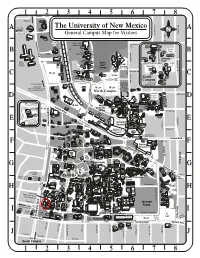

12345678 Q Lot to Bldg. 259 277 Girard Blvd. Princeton Dr. to Lands 283 The University of New Mexico A West Lot A 277 N Camino de Salud General Campus Map for Visitors Dr. Vassar 271 265 University Blvd. CNG Bus Only Station Pete & Nancy Domenici Hall Constitution Ave. 341 339 217 260 I Lot Student Yale Blvd. 332 Camino de Salud University Blvd. Family B Casa Stanford Dr. B 333 331 Housing KNME-TV Esperanza 317-329 270 262 337 218 338 Isotopes Park Buena Vista Dr. Carrie 240 243 Tingley 272 North Avenida De Cesar Chavez South Golf Law 301 Lot Hospital 233 241 239 School “The Pit” Zia Course Closed Lot 302 237 236B 230 Mountain Rd. G Lot 312 307 C 223 206 L Lot Stanford Dr. C 242 South 308 238 236A Tucker Rd. Campus 311 Tucker Rd. Domenici to South To Lands West Education Golf Course 311A To Bldg. 259 216 Center C 208 M Lot M Lot 1634 University Blvd. NE C a m Construction a Continuing Education m in Site i o North Campus n o d e d 231 Marble Ave. e S a Yale Blvd. University S l e u D r d 249 D v Psychiatric 246 ic 273 204 o 248 234 266 Services 225 Elks - Recycling 268 Political Archives 228 U M Lot Health 247 n Lomas Blvd. 253 i 226 v Continuing Sciences 229 e T Lot 211 r Education 212 s Center 264 Frontier Ave. i 205 t y 259 201 B l v 258 203 255 d 183 Girard Blvd. -

Multi-Periodic Pulsations of a Stripped Red Giant Star in an Eclipsing Binary

1 Multi-periodic pulsations of a stripped red giant star in an eclipsing binary Pierre F. L. Maxted1, Aldo M. Serenelli2, Andrea Miglio3, Thomas R. Marsh4, Ulrich Heber5, Vikram S. Dhillon6, Stuart Littlefair6, Chris Copperwheat7, Barry Smalley1, Elmé Breedt4, Veronika Schaffenroth5,8 1 Astrophysics Group, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK. 2 Instituto de Ciencias del Espacio (CSIC-IEEC), Facultad de Ciencias, Campus UAB, 08193, Bellaterra, Spain. 3 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK. 4 Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK. 5 Dr. Karl Remeis-Observatory & ECAP, Astronomical Institute, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Sternwartstr. 7, 96049, Bamberg, Germany. 6 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, S3 7RH, UK. 7Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, Twelve Quays House, Egerton Wharf, Birkenhead, Wirral, CH41 1LD, UK. 8Institute for Astro- and Particle Physics, University of Innsbruck, Technikerstrasse. 25/8, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria. Low mass white dwarfs are the remnants of disrupted red giant stars in binary millisecond pulsars1 and other exotic binary star systems2–4. Some low mass white dwarfs cool rapidly, while others stay bright for millions of years due to stable 2 fusion in thick surface hydrogen layers5. This dichotomy is not well understood so their potential use as independent clocks to test the spin-down ages of pulsars6,7 or as probes of the extreme environments in which low mass white dwarfs form8–10 cannot be fully exploited. Here we present precise mass and radius measurements for the precursor to a low mass white dwarf. -

UNM Building List

UNM Building List Non- Bldg Assignable Assignable Efficiency Campus Site Name Street City State Zip Year Built Status Gross Sq Ft Usable Sq Ft Sq Ft Sq Ft Ratio Group Albuquerque A0002 - Engineering and Science Computer Pod 201 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1916 OPEN 7,423 6,550 5,762 788 78% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0004 - Elizabeth Waters Center for Dance at Carlisle Gymnasium 301 Yale Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1928 OPEN 37,545 34,805 28,302 6,503 75% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0008 - Bandelier Hall East 401 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1930 OPEN 10,084 8,510 6,276 2,234 62% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0009 - Marron Hall 201 Yale Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1931 OPEN 27,475 19,405 11,577 7,828 42% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0010 - Scholes Hall 1800 Roma Ave. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1936 OPEN 51,160 45,023 32,546 12,477 65% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0011 - Anthropology 500 University Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1937 OPEN 57,668 50,900 40,347 10,553 70% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0012 - Anthropology Annex 301 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 1937 OPEN 9,321 8,046 6,033 2,013 65% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0014 - Science and Mathematics Learning Center 311 Terrace St. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 2010 OPEN 74,662 66,271 43,606 22,665 58% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0015 - Hibben Center for Archaeology Research 450 University Blvd. N.E. Albuquerque NM 87131 2001 OPEN 37,922 34,751 26,565 8,186 70% CENTRAL Albuquerque A0016 - Bandelier Hall West 400 University Blvd. -

Rio Puerco Resource Management Draft Plan & Environmental Impact Statement

Rio Puerco Resource Management Draft Plan & Environmental Impact Statement Volume III August 2012 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Albuquerque District Rio Puerco Field Office TABLE OF CONTENTS A CULTURAL RESOURCES ON NON-BLM LANDS LISTED ON THE NRHP ........ A-1 B DESCRIPTION OF GRAZING ALLOTMENTS BY ACREAGE AND AUMS ......... B-1 C EXAMPLES OF PRESCRIBED GRAZING SYSTEMS .............................................. C-1 C.1 Rest-Rotation Grazing ................................................................................................ C-1 C.2 Deferred Rotation Grazing .......................................................................................... C-1 C.3 Deferred Grazing ........................................................................................................ C-1 C.4 Alternate Grazing ........................................................................................................ C-1 C.5 Short-Duration, High-Intensity Grazing ..................................................................... C-2 D RANGELAND IMPROVEMENTS ............................................................................... D-1 D.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. D-1 D.2 Structural Improvements ............................................................................................. D-1 D.2.1 Fences .............................................................................................................................. -

The Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2015 the Housing Cost Conundrum

UNDERSTANDING BOSTON The Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2015 The Housing Cost Conundrum Barry Bluestone James Huessy Eleanor White Charles Eisenberg Tim Davis with assistance from William Reyelt Prepared by The Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy Northeastern University for The Boston Foundation Edited by Rebecca Koepnick Mary Jo Meisner Kathleen Clute The Boston Foundation November 2015 The Boston Foundation, Greater Boston’s community foundation, is one of the largest community foundations in the nation, with net assets of some $1 billion. In 2014, the Foundation and its donors made more than $112 million in grants to nonprofit organizations and received gifts of nearly $112 million. In celebration of its Centennial in 2015, the Boston Foundation has launched the Campaign for Boston to strengthen the Permanent Fund for Boston, the only endowment fund focused on the most pressing needs of Greater Boston. The Foundation is proud to be a partner in philanthropy, with more than 1,000 separate charitable funds established by donors either for the general benefit of the community or for special purposes. The Boston Foundation also serves as a major civic leader, think tank and advocacy organization, commissioning research into the most critical issues of our time and helping to shape public policy designed to advance opportunity for everyone in Greater Boston. The Philanthropic Initiative (TPI), an operating unit of the Foundation, designs and implements customized philanthropic strategies for families, foundations and corporations around the globe. For more information about the Boston Foundation and TPI, visit tbf.org or call 617-338-1700. -

Health of Boston 2014-2015 Martin J

Prepared by the Boston Public Health Commission Health of Boston 2014-2015 Martin J. Walsh, Mayor, City of Boston Paula Johnson, MD, MPH, Chair Board of the Boston Public Health Commission HuyHuy Nguyen,Nguyen, MD,MD, InterimInterim ExecutiveExecutive Director and Medical Director Building a Healthy Boston Boston Public Health Commission Health of Boston 2014-2015 Copyright Information All material contained in this report is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without special permission; however, citation as to the source is appropriate. Suggested Citation Health of Boston 2014-2015: Boston Public Health Commission Research and Evaluation Office Boston, Massachusetts 2015 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by Snehal N. Shah, MD, MPH; H. Denise Dodds, PhD, MCRP, MEd; Dan Dooley, BA; Phyllis D. Sims, MS; S. Helen Ayanian, BA; Neelesh Batra, MSc; Alan Fossa, MPH; Shannon E. O’Malley, MS; Dinesh Pokhrel, MPH; Elizabeth Russo, MD, MPH; Rashida Taher, MPH; Sarah Thomsen- Ferreira, M.S.; Megan Young, MHS; Jun Zhao, PhD. The cover was designed by Lisa Costanzo, BFA. Health of Boston 2014-2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

National Register of Historic Places AUG 8 M Continuation Sheet NATIONAL REGISTER 11 Section Number ____ Page ____

NP£ Form 1&«)0-a QMS Appnovd No. 1024-O018 United States Department of the Interior RECEIVED National Park Service National Register of Historic Places AUG 8 m Continuation Sheet NATIONAL REGISTER 11 Section number ____ Page ____ 1. Name Art Annex 2. Location street & number: NE corner of Central Ave. and Terrace St., UNM city, town: Albuquerque state: New Mexico code: 035 county: Bemalillo code: NM-001 3. Classification Category: Building Ownership: Public Status: Occupied Present Use: Class Rooms 4. Owner of Property name: Regents of the University of New Mexico street & number: Scholes Hall, University of New Mexico city, town: Albuquerque state: New Mexico 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, etc.: Bernalillo County Courthouse street & number: One Civic Plaza city, town: Albuquerque state: New Mexico 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Not applicable. 7. Description Condition: Good Description: The Art Annex is a square, flat roofed Spanish Pueblo Revival style building with large pane windows. The exterior finish is stucco with no ornamentation except for vigas protruding from the exterior walls above the building's entrance and between the windows. The building has very large milti-lite metal pane windows with no lintels or sills. The entrance is recessed with metal leaf doors with side lites and a sculpture in the transom. The building was designed by the architectural firm of Trost and Trost and built in 1926. The Art Annex was the first library at UNM. Presently it is used for classrooms. 8. Significance Period: 1900- Areas of Significance: Architecture, education Dates: 1926 Builder/Architect: Trost & Trost Statement of Significance, Criterion A & C: The Art Annex is one of six buildings on the campus of the University if New Mexico included in this nomination. -

Orbridge — Educational Travel Programs for Small Groups

For details or to reserve: wm.orbridge.com (866) 639-0079 APRIL 10, 2021 – APRIL 14, 2021 POST-TOUR: APRIL 14, 2021 — APRIL 16, 2021 CIVIL RIGHTS—A JOURNEY TO FREEDOM The Alabama cities of Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma birthed the national leadership of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, when tens of thousands of people came together to advance the cause of justice against remarkable odds and fierce resistance. In partnership with the non-profit Alabama Civil Rights Tourism Association and in support of local businesses and communities, Orbridge invites you to experience the people, places, and events igniting change and defining a pivotal period for America that continues today. Dive deeper beyond history's headlines to the newsmakers, learning from actual foot soldiers of the struggle whose vivid and compelling stories bring a history of unforgettable tragedy and irrepressible triumph to life. Dear Alumni and Friends, Join us for an intimate and essential opportunity to explore the Deep South with an informative program that highlights America’s civil rights movement in Alabama. Historically, perhaps no other state has played as vital a role, where a fourth of the official U.S. Civil Rights Trail landmarks are located. On this five-day journey, discover sites that advanced social justice and shifted the course of history. Stand in the pulpit at Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. preached, walk over the Edmund Pettus Bridge where law enforcement clashed with voting rights marchers, and gather with our group at Kelly Ingram Park as 1,000 or so students did in the 1963 Children’s Crusade. -

Residential Adobe Architecture Around Santa Fe

RESIDENTIAL ADOBE ARCHITECTURE AROUND SANTA FE AND TAOS FROM 1900 TO THE PRESENT by HAMIYET OZEN, B.S. in Arch. A THESIS IN ARCHITECTURE Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech Unlversity in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE Approved Chairperson of the Committee Ac^épted Dean^of the Graduate School December, 1990 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Prof. WiUard B. Robinson for directing this project, and Prof. John P. White and Dr. Joseph E. King, for their beneficial suggestions. I also would like to thank Barbara Walker for editing and being supfx^rtive during the writing process of this project. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii LISTOFHGURES iv I. INTRODUCnON 1 II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND HISTORICAL USE OF ADOBE 8 Pueblo Indian Architecture 9 Spanish Colonial and Mexican Architecture 13 American Period Territorial and Railroad Style 16 Revival Style 23 III. HISTORIC PRESERVATION OF ADOBE BUa.DINGS 31 Preservation Problems 34 Rehabilitation and Preservation of Adobe Structures 37 Stabilization of Adobe 42 IV. ARCHITECTURAL AND CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF RESIDENTIAL ADOBE 45 Evolution of Residential Architecture 45 Popularity of Residential Adobe Architecture 59 V. PRODUCTION AND MANUFACTURING OF ADOBE 67 Production of Adobe Bricks 68 Production Methods of Adobe Bricks 73 VL CONCLUSION 78 ENDNOTES 83 BIBLIOGRAPHY 88 ui LIST OF FIGURES 1. The map of the region 2 2. Taos Pueblo Multistoried North Plaza Building 11 3. The plan of Taos center 11 4. Palace of the Govemors which was built in 1610 and is the oldest public building in the United States 14 5.