Saint-Gaudens' Shaw Memorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Properties Relating to Harriet Tubman in Auburn, New York

(June 1991) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM This form is for use in documenting multiple p to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Documentation Form (National Register Bulleti em by entering the requested information. For additional space, (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all itemsT [x] New Submission [ ] Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Properties Relating to Harriet Tubman in Auburn, New York B. Associated Historic Contexts___________________________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period of each.) Harriet Tubman's life, activities and commemoration in Auburn, N.Y., 1859-1913. C. Form Prepared by name/title Susanne R. Warren. Architectural Historian/Consultant organization __ date _ October 27. 1998 street & number 101 Monument Avenue telephone 802-447-0973 city or town __ Benninaton state Vermont zip code 05201________ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. ([ 3 See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature' of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Registej 4/2/99 Date of Action NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. -

National Mall Existing Conditions

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Mall and Memorial Parks Washington, D.C. Photographs of Existing Conditions on the National Mall Summer 2009 and Spring 2010 CONTENTS Views and Vistas ............................................................................................................................ 1 Views from the Washington Monument ................................................................................. 1 The Classic Vistas .................................................................................................................... 3 Views from Nearby Areas........................................................................................................8 North-South Views from the Center of the Mall ...................................................................... 9 Union Square............................................................................................................................... 13 The Mall ...................................................................................................................................... 17 Washington Monument and Grounds.......................................................................................... 22 World War II Memorial................................................................................................................. 28 Constitution Gardens................................................................................................................... 34 Vietnam Veterans Memorial........................................................................................................ -

World War II-Related Exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art

National Gallery of Art: Research Resources Relating to World War II World War II-Related Exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art During the war years, the National Gallery of Art presented a series of exhibitions explicitly related to the war or presenting works of art for which the museum held custody during the hostilities. Descriptions of each of the exhibitions is available in the list of past exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art. Catalogs, brochures, press releases, news reports, and photographs also may be available for examination in the Gallery Archives for some of the exhibitions. The Great Fire of London, 1940 18 December 1941-28 January 1942 American Artists’ Record of War and Defense 7 February-8 March 1942 French Government Loan 2 March 1942-1945, periodically Soldiers of Production 17 March-15 April 1942 Three Triptychs by Contemporary Artists 8-15 April 1942 Paintings, Posters, Watercolors, and Prints, Showing the Activities of the American Red Cross 2-30 May 1942 Art Exhibition by Men of the Armed Forces 5 July-2 August 1942 War Posters 17 January-18 February 1943 Belgian Government Loan 7 February 1943-January 1946 War Art 20 June-1 August 1943 Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Drawings and Watercolors from French Museums and Private Collections 8 August-5 September 1943 (second showing) Art for Bonds 12 September-10 October 1943 1DWLRQDO*DOOHU\RI$UW:DVKLQJWRQ'&*DOOHU\$UFKLYHV ::,,5HODWHG([KLELWLRQVDW1*$ Marine Watercolors and Drawings 12 September-10 October 1943 Paintings of Naval Aviation by American Artists -

ST PAUL's ROCK CREEK CEMETERY.Pdf

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: October 8, 2018 CONTACT: Michael Mitchell 202-671-2338 [email protected] OCTFME Recognizes St. Paul’s Rock Creek Cemetery as the October 2018 Location of the Month Washington, D.C. -- The Office of Cable Television, Film, Music and Entertainment (OCTFME) recognizes St. Paul’s Rock Creek Cemetery as the October 2018 Location of the Month, a fitting choice for the month of Halloween! St. Paul’s Rock Creek Cemetery is a gem of hidden tranquility in the midst of an urban setting. Lush landscape, breathtaking sculptures and notable history combined makes Rock Creek Cemetery the most beautiful and evocative public cemetery in the nation’s capital. Located at Rock Creek Church Road, NW, and Webster Street, NW, in the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, DC, it is the city’s oldest cemetery. Dating from 1719, the Cemetery was designed as part of the rural cemetery movement first advocated by the architect Sir Christopher Wren in 1711. The burial ground in the churchyard’s urban space, with its natural 86-acre rolling landscape, functions as both cemetery and public park. The beautiful landscape, the Cemetery’s famous residents, and the stunning variety of sculptures and monuments make Rock Creek Cemetery a place of pilgrimage for people of all faiths and an excellent setting for film, television and event productions. Rock Creek Cemetery serves as the final resting place to some of Washington’s most notable residents including (in alphabetical order): Henry Adams, Author and diplomat Eugene Allen, White House butler for 34 years and inspiration for the 2013 movie, “The Butler” Abraham Baldwin, Signer of the U.S. -

Btn-Colonel-Robert-Gould-Shaw-Letter

Created by: Carmen Harshaw and Susan Wells, Schaefer Middle School Grade level: 8 Primary Source Citation: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw to his wife Annie, June 9, 1863, St. Simon’s Island, GA, in Russell Duncan, Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (Civil War Talk web site). https://civilwartalk.com/threads/a- letter-by-colonel-robert-gould-shaw.74819/ Allow students, in groups or individually, to examine the letter at the above link while answering the questions below in order. The questions are designed to guide students into a deeper analysis of the source and sharpen associated cognitive skills. This letter was used as an introduction to the movie Glory. Students will learn about the role African American soldiers played in the Civil War and about the similarities and differences between the U.S. Colored Troops and other U.S. forces. Level I: Description 1. What were the dates of the letter to Annie from Colonel Shaw? 2. Where did the raid described in the letter occur? 3. What war was this raid part of? 4. Which side was Colonel Shaw on? North or South? Union or Confederate? Level II: Interpretation 1. Why did Colonel Shaw talk about the beauty of the south in his letter to his wife? 2. Using context clues, what does the word disemboweled mean? 3. Why did Colonel Shaw tell Annie not to tell anyone about the raid on Darien? Level III: Analysis 1. Colonel Shaw called the raid on Darien a “dirty piece of business.” What evidence does he give to support this claim? 2. -

Boston Common and the Public Garden

WalkBoston and the Public Realm N 3 minute walk T MBTA Station As Massachusetts’ leading advocate for safe and 9 enjoyable walking environments, WalkBoston works w with local and state agencies to accommodate walkers | in all parts of the public realm: sidewalks, streets, bridges, shopping areas, plazas, trails and parks. By B a o working to make an increasingly safe and more s attractive pedestrian network, WalkBoston creates t l o more transportation choices and healthier, greener, n k more vibrant communities. Please volunteer and/or C join online at www.walkboston.org. o B The center of Boston’s public realm is Boston m Common and the Public Garden, where the pedestrian m o network is easily accessible on foot for more than o 300,000 Downtown, Beacon Hill and Back Bay workers, n & shoppers, visitors and residents. These walkways s are used by commuters, tourists, readers, thinkers, t h talkers, strollers and others during lunch, commutes, t e and on weekends. They are wonderful places to walk o P — you can find a new route every day. Sample walks: u b Boston Common Loops n l i • Perimeter/25 minute walk – Park St., Beacon St., c MacArthur, Boylston St. and Lafayette Malls. G • Central/15 minute walk – Lafayette, Railroad, a MacArthur Malls and Mayor’s Walk. r d • Bandstand/15 minute walk – Parade Ground Path, e Beacon St. Mall and Long Path. n Public Garden Loops • Perimeter/15 minute walk – Boylston, Charles, Beacon and Arlington Paths. • Swans and Ducklings/8 minute walk – Lagoon Paths. Public Garden & Boston Common • Mid-park/10 minute walk – Mayor’s, Haffenreffer Walks. -

Geographical List of Public Sculpture-1

GEOGRAPHICAL LIST OF SELECTED PERMANENTLY DISPLAYED MAJOR WORKS BY DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH ♦ The following works have been included: Publicly accessible sculpture in parks, public gardens, squares, cemeteries Sculpture that is part of a building’s architecture, or is featured on the exterior of a building, or on the accessible grounds of a building State City Specific Location Title of Work Date CALIFORNIA San Francisco Golden Gate Park, Intersection of John F. THOMAS STARR KING, bronze statue 1888-92 Kennedy and Music Concourse Drives DC Washington Gallaudet College, Kendall Green THOMAS GALLAUDET MEMORIAL; bronze 1885-89 group DC Washington President’s Park, (“The Ellipse”), Executive *FRANCIS DAVIS MILLET AND MAJOR 1912-13 Avenue and Ellipse Drive, at northwest ARCHIBALD BUTT MEMORIAL, marble junction fountain reliefs DC Washington Dupont Circle *ADMIRAL SAMUEL FRANCIS DUPONT 1917-21 MEMORIAL (SEA, WIND and SKY), marble fountain reliefs DC Washington Lincoln Memorial, Lincoln Memorial Circle *ABRAHAM LINCOLN, marble statue 1911-22 NW DC Washington President’s Park South *FIRST DIVISION MEMORIAL (VICTORY), 1921-24 bronze statue GEORGIA Atlanta Norfolk Southern Corporation Plaza, 1200 *SAMUEL SPENCER, bronze statue 1909-10 Peachtree Street NE GEORGIA Savannah Chippewa Square GOVERNOR JAMES EDWARD 1907-10 OGLETHORPE, bronze statue ILLINOIS Chicago Garfield Park Conservatory INDIAN CORN (WOMAN AND BULL), bronze 1893? group !1 State City Specific Location Title of Work Date ILLINOIS Chicago Washington Park, 51st Street and Dr. GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, bronze 1903-04 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, equestrian replica ILLINOIS Chicago Jackson Park THE REPUBLIC, gilded bronze statue 1915-18 ILLINOIS Chicago East Erie Street Victory (First Division Memorial); bronze 1921-24 reproduction ILLINOIS Danville In front of Federal Courthouse on Vermilion DANVILLE, ILLINOIS FOUNTAIN, by Paul 1913-15 Street Manship designed by D.C. -

Adams Memorial (Rock Creek Cemetery)

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1*69) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY E-N-TRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) 1 0 Adams Memorial (Rock Creek Cemetery) AND/OR HISTORIC: "Grief"; "Peace of God" STREET AND NUMBER: Webster Street and Rock Creek Church Road, N.W CITY OR TOWN: Washington COUNTY: District of Columbia 11 District of Columbia 0.01 11 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District D Building Public Public Acquisition: [~| Occupied Yes: |X] Restricted Site I | Structure Private || In Process EC] Unoccupied | | Unrestricted Object Both | | Being Considered | 1 Preservation work in progress D No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) I I Agricultural Q Government D Park I I Transportation I | Comments Q Commercial Q Industrial I | Private Residence E&] Other (Specify) [ | Educational Q Military fcH Religious Memorial I | Entertainment [| Museum I | Scientific OWNER©S NAME: Adams Memorial Society Rock Creek Cemetery STREET AND NUMBER: Webster Street and Rock Creek Church Road. N.W Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE: Washington District of Columbia 11 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Recorder of Deeds STREET AND NUMBER: 6th and D Streets, N.W, Cl TY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia 11 TITLE OF suRVEY:proposed District of Columbia Additions to the National Regis- ter of Historic Properties recommended by the Joint Committee on Landmarks DATE OF SURVEY: March 7, 1968 Federal State -

University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN EAU CLAIRE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION Study Abroad UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW, GLASGOW, SCOTLAND 2020 Program Guide ABLE OF ONTENTS Sexual Harassment and “Lad Culture” in the T C UK ...................................................................... 12 Academics .............................................................. 5 Emergency Contacts ...................................... 13 Pre-departure Planning ..................................... 5 911 Equivalent in the UK ............................... 13 Graduate Courses ............................................. 5 Marijuana and other Illegal Drugs ................ 13 Credits and Course Load .................................. 5 Required Documents .......................................... 14 Registration at Glasgow .................................... 5 Visa ................................................................... 14 Class Attendance ............................................... 5 Why Can’t I fly through Ireland? ................... 14 Grades ................................................................. 6 Visas for Travel to Other Countries .............. 14 Glasgow & UWEC Transcripts ......................... 6 Packing Tips ........................................................ 14 UK Academic System ....................................... 6 Weather ............................................................ 14 Semester Students Service-Learning ............. 9 Clothing............................................................ -

Off the High Horse: Human-Animal Relations on Public Monuments

Off the High Horse: Human-Animal Relations on Public Monuments This month, the suit concerning the removal of the equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond, VA will proceed to trial. A different way to deal with a troubling monument is to place another one nearby to convey an opposing message, and several such corrective statues have appeared near Monument Avenue over the past twenty-five years. In this paper I explore two of these, focusing on the role of the horse. Although the spirited stallion in Kehinde Wiley’s “Rumors of War” (2019) stands in marked contrast to the emaciated beast of burden in Tessa Pullan’s “War Horse” (1997), I argue that both depictions have their roots in antiquity: the former in monumental art, the latter in literature. Thus Wiley’s sculpture adapts the tradition of the equestrian statue, popular in both Greece and Rome, using the animal to showcase the power and superiority of the human rider, while Pullan’s invites viewers to reach beyond the social constructs of friend and foe as well as boundaries of species between human and animal in a manner reminiscent of Homer. In an equestrian statue the horse serves multiple functions; from a practical perspective, it elevates the honoree to a point of greater visibility, while on a more symbolic level it can illustrate characteristics of the rider. In the statue of Marcus Aurelius from the Capitoline Hill, for example, both horse and rider assume a calm and balanced posture, while Wiley’s ensemble exaggerates the impetuous movement of his model, Moynihan’s equestrian statue of Stuart (1907), but also evokes more distant predecessors, from Mills’ groundbreaking depiction of Andrew Jackson (1853) all the way to the Alexander Mosaic and the cavalcade on the Parthenon freeze. -

David Boitnott Wins ANA “Best of Show” Exhibit Award

RALEIGH COIN CLUB NNeewwsslleetttteerr Established in 1954 April 2003 In This Issue David Boitnott Wins ANA “Best of Show” Exhibit Award ARTICLES By Dave Provost David Boitnott Wins ANA “Best of Show” Exhibit Award From the moment it was set up, it was clear that David Saint-Gaudens Exhibition at Boitnott’s exhibit “Wanted: A Few Oddball North Carolinians: NC Museum of Art North Carolina Statehood Quarter Errors” was the exhibit to Wright Brothers Seminar beat at this year’s ANA National Money Show in Charlotte. Planned at NC Collection Gallery More than 40 exhibits were dealers who knew of his efforts National Wildlife Refuge mounted at the show, but none to assemble a definitive NC System Centennial Medals could top the tremendous quarter error collection, a display created by RCC member number of his “oddballs” were and Director David Boitnott. either purchased from general- REGULAR FEATURES purpose dealers at coin shows The four-case exhibit show- or won via eBay online auctions. Club Business cased a comprehensive array of possible planchet, die and By winning the Best-of-Show President’s Message striking errors through the use of award at the springtime National North Carolina Statehood Money Show, the exhibit is North Carolina quarters. The exhibit was automatically eligible to compete Numismatic Showcase creative, attractive, interesting for the same prize at the ANA’s for collectors and non-collectors annual convention — the Numismatic News from alike and provided plenty of World’s Fair of Money — without Outside the Triangle detailed information for the having to first win its category. -

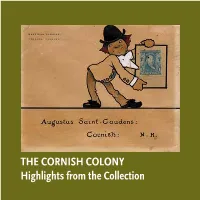

The Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection the Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection

THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection The Cornish Colony, located in the area of Cornish, New The Cornish Colony did not arise all of apiece. No one sat down at Hampshire, is many things. It is the name of a group of artists, a table and drew up plans for it. The Colony was organic in nature, writers, garden designers, politicians, musicians and performers the individual members just happened to share a certain mind- who gathered along the Connecticut River in the southwest set about American culture and life. The lifestyle that developed corner of New Hampshire to live and work near the great from about 1883 until somewhere between the two World Wars, American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Colony is also changed as the membership in the group changed, but retained a place – it is the houses and landscapes designed in a specific an overriding aura of cohesiveness that only broke down when the Italianate style by architect Charles Platt and others. It is also an country’s wrenching experience of the Great Depression and the ideal: the Cornish Colony developed as a kind of classical utopia, two World Wars altered American life for ever. at least of the mind, which sought to preserve the tradition of the —Henry Duffy, PhD, Curator Academic dream in the New World. THE COLLECTION Little is known about the art collection formed by Augustus Time has not been kind to the collection at Aspet. Studio fires Saint-Gaudens during his lifetime. From inventory lists and in 1904 and 1944 destroyed the contents of the Paris and New correspondence we know that he had a painting by his wife’s York houses in storage.