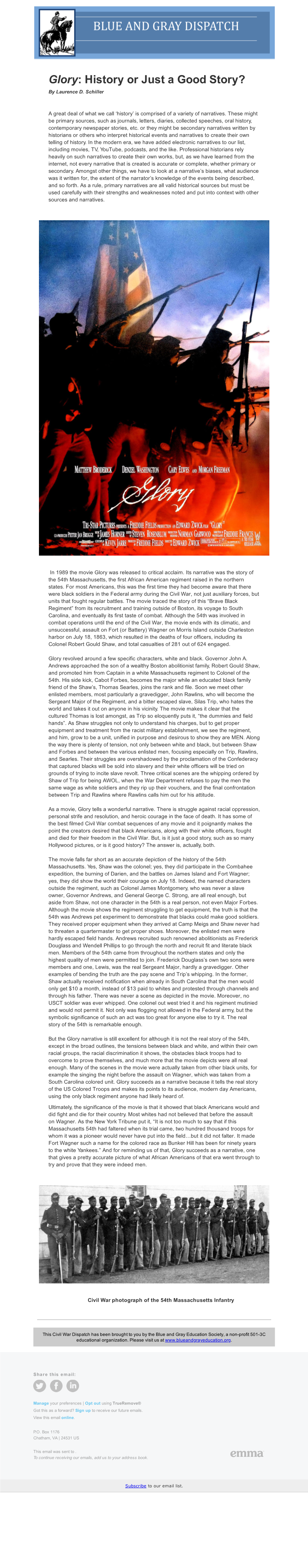

Glory: History Or Just a Good Story? by Laurence D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Properties Relating to Harriet Tubman in Auburn, New York

(June 1991) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM This form is for use in documenting multiple p to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Documentation Form (National Register Bulleti em by entering the requested information. For additional space, (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all itemsT [x] New Submission [ ] Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Properties Relating to Harriet Tubman in Auburn, New York B. Associated Historic Contexts___________________________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period of each.) Harriet Tubman's life, activities and commemoration in Auburn, N.Y., 1859-1913. C. Form Prepared by name/title Susanne R. Warren. Architectural Historian/Consultant organization __ date _ October 27. 1998 street & number 101 Monument Avenue telephone 802-447-0973 city or town __ Benninaton state Vermont zip code 05201________ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. ([ 3 See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature' of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Registej 4/2/99 Date of Action NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. -

Btn-Colonel-Robert-Gould-Shaw-Letter

Created by: Carmen Harshaw and Susan Wells, Schaefer Middle School Grade level: 8 Primary Source Citation: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw to his wife Annie, June 9, 1863, St. Simon’s Island, GA, in Russell Duncan, Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (Civil War Talk web site). https://civilwartalk.com/threads/a- letter-by-colonel-robert-gould-shaw.74819/ Allow students, in groups or individually, to examine the letter at the above link while answering the questions below in order. The questions are designed to guide students into a deeper analysis of the source and sharpen associated cognitive skills. This letter was used as an introduction to the movie Glory. Students will learn about the role African American soldiers played in the Civil War and about the similarities and differences between the U.S. Colored Troops and other U.S. forces. Level I: Description 1. What were the dates of the letter to Annie from Colonel Shaw? 2. Where did the raid described in the letter occur? 3. What war was this raid part of? 4. Which side was Colonel Shaw on? North or South? Union or Confederate? Level II: Interpretation 1. Why did Colonel Shaw talk about the beauty of the south in his letter to his wife? 2. Using context clues, what does the word disemboweled mean? 3. Why did Colonel Shaw tell Annie not to tell anyone about the raid on Darien? Level III: Analysis 1. Colonel Shaw called the raid on Darien a “dirty piece of business.” What evidence does he give to support this claim? 2. -

Glory Movie Worksheet-EDAY2.Pdf

Civil Rights Name _________________________________ Hainline Date _________ Pd ________ “Glory” Learning Target: Students will be able to identify key elements from the film, “Glory” and apply them to the Civil War. Glory is the story of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Regiment, the first regular army regiment of African American soldiers commissioned during the Civil War. At the beginning of the war, most people believed that African Americans could not be disciplined to make good soldiers in a modern war and that they would run when fired upon or attacked. Colonel Shaw, a white abolitionist, and hundreds of soldiers in his regiment, all African American volunteers, gave their lives to prove that African American men could fight as well as whites. Known as the “Swamp Angels” because much of the regiment’s duties were in the swamps and the marshes of the South, the 54th fought bravely and with great success. One of the more notable members of the regiment was Lewis Douglass, son of Frederick Douglass. Although the 54th was instrumental in several early battles and is generally responsible for encouraging many other African Americans to enlist in the Union Army, they were never given the respect that white soldiers were. Even though Lincoln credits African American soldiers for turning the tide of the war, not one African American regiment was involved in the Union parade in front of the White House after the war ended. Please answer the following questions while watching the movie or as you reflect after class. 1. Identify the following people: a. -

Lesson 4: African-Americans in the Civil War Class Notes 4: Teacher

Lesson 4: African-Americans in the Civil War Class Notes 4: Teacher Edition I. Emancipation Proclamation Some Northerners felt that just winning the war wouldn’t be enough if slavery still existed. Lincoln disliked slavery, but he did not think the federal government had the power to abolish it where it already existed. His primary goal was to re-unify the country. Later, he used his power as commander-in-chief to free the slaves. Since slave labor was used by the South to build railroads and grow food , Lincoln could consider the slaves to be enemy resources. As U.S. commander -in-chief, Lincoln could seize these enemy resources Æ meaning Lincoln could emancipate the slaves. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It applied to slaves living in Confederate control – NOT to slaves living in Southern areas under Union control NOR to slaves that lived in the border states. This document made the destruction of slavery a Northern war aim. It also discouraged the interference of foreign governments. II. Frederick Douglass Douglass was a former slave who became an important abolitionist . He traveled extensively giving lectures about the horrors of slavery and the need to abolish it. For Douglas and other abolitionists, the Civil War was a war to end slavery. Throughout the war, Douglass worked toward emancipating slaves and the right for African-Americans to enlist in the Union army . He met with President Lincoln to discuss these issues. Douglass helped recruit African-American soldiers. He believed that if former slaves and other African-Americans fought in the war, they could not be denied full citizenship in the Union. -

H I S T O R I C D I S T R I C T

S H A W H I S T O R I C D I S T R I C T S H A W H I S T O R I C D I S T R I C T Unlike many of Washington’s neighborhoods, Shaw was not fashioned by developers who built strings of nearly identical rowhouses. Rather, Shaw was settled by individuals who constructed their own single dwellings of frame and brick, which were later infilled with small rows of developer-built speculative housing. Originally Shaw was in a part of the District called the Northern Liberties, north of the line where livestock were required to be penned and so were able to roam freely. Initially an ethnically and economically diverse neighborhood, Shaw was home to European immigrants and free African Americans, and, during and after the Civil War, increasing numbers of southern Freedmen flooding to cities in search of work. The name Shaw came into use in the mid-20th century to define the area around Shaw Junior High School, which was named for Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, leader of the all-black 54th Massachusetts Regiment. The brick residence at 1243 10th Street, built c. 1850, reflects typical early masonry construction in Shaw. HPO Photo. The Shaw neighborhood developed primarily along 7th Street, which was part of L’Enfant’s plan for the city and extended as far north as Boundary Street (now Florida Avenue). Beyond that, 7th Street became a toll road leading north from the District into the farmlands of Montgomery County. This turnpike provided Maryland farmers with direct access to the markets and wharves of the city and, after it was paved in 1818, became one of the city’s busiest thoroughfares. -

Tubman Home for the Aged/Harriet Tubman Residence/Thompson

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 TUBMAN HOME FOR THE AGED, HARRIET TUBMAN RESIDENCE AND THOMPSON A.M.E. ZION CHURCH Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service__________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: TUBMAN HOME FOR THE AGED, HARRIET TUBMAN RESIDENCE, THOMPSON A.M.E. ZION CHUCH Other Name/Site Number: Harriet Tubman District Properties Relating to Harriet Tubman in Auburn, NY 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 180 South Street Not for publication: 182 South Street 33 Parker Street City/Town: Auburn Vicinity: State: NY County: Cayuga Code: Oil Zip Code: 13201 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-Local: __ District: ___ Public-State: __ Site: ___ Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 3 4 buildings _ sites __ structures __ objects 4 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 4 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: (National Register)Historic Properties Relating to Harriet Tubman in Auburn, New York 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 TUBMAN HOME FOR THE AGED, HARRIET TUBMAN RESIDENCE AND THOMPSON A.M.E. ZION CHURCH Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Swamp Angels: a Biographical Study of the 54Th Massachusetts Regiment

IiJJUJ'( BRANCH A Biographical Study ofthe 54th Massachusetts Regiment THE GAllANT CHARGE OF HtE; rtfT'( roURTH MASSACftUSETTS (COLORED) RE.GIMENT. {IX 1.4< fi·,k.! "..,.h,,1 );"1'& ~..u; ""l/w'ritl4Id"./ !'t4tV {:-WluUtIf', Jl4{li NIt! 1664, If" ~"",;f('44tMt,f lill;/: {J.Su,... TRUE FACTS ABOUT THE BLACK DEFENDERS OF THE CIVIL WAR ROBERT EWELL GREENE BoMarklGreene Publishing Group I 1990 54th Massachusetts Regiment 7 A Sequence ofEvents The history books and sometimes novels and documentations will show that the slaves were freed by a document called the Emancipation Proclamation during the course of the Civil War. The former slaves were assisted in the process of their eventual freedom, but credit must be given to those men of black and white skin colors who were present at the battlefields and shed their blood and felt the pain of their wounds and some answered to the calls of taps and others suffered through the years from their battle wounds. The presence of these sable color men on the battlefield were not the primary desires of the majority rule but a small minority of concerned and humble white and black Americans who had tasted the good recipe of freedom in the northern states and were enjoying the prosperity of America's economic system. Some ofthese individuals were called abolitionists, they believed in the eradication of the most cruel system of bondage. The dehumanizing and family divider, and blueprint of illiteracy and ignorance that had permeated the culture of a proud African people on foreign shores. Their concerns were present when the Civil War commenced. -

Robert Gould Shaw, Who Com- Manded the Regiment in Which Douglass' Two Sons Fought

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Scrapbooks Collection ' ROBERT GOULD SHAW, WHO COM- MANDED THE REGIMENT IN WHICH DOUGLASS' TWO SONS FOUGHT. MAJOR F. S. CUNNINGHAM, WHO WAS INTIMATELY ASSOCIATED WITH DOUGLASS AND WHO FOUGHT IN THE SAME REGIMENT WITH THE DEAD STATESMAN'S SONS. ' Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Scrapbooks Collection .--I PABLOB OF THE OLD POST Fred Douglass went to her house when Joseph Post of Charlotte, Two sisters he first visited Rochester, and all of the survive her, Mrs. Willis of Rochester anti-slavery advocates, including Will- and Mrs. Mary Post of Longlsland. In iam Lloyd Garrison, made her resi- addition to these relatives she leaves 14 DEATH OF MRS. AMY POST. dence their home when in Rochester. "•randchildren and four great-grand- On one visit Fred Douglass dropped a children. The time for the funeral paper from his pocket headed "List of will be announced hereafter. words I don't know how to spell." CAREER OF A FAMOUS The deceased never wavered in WOMAN CLOSED. her devotion to the cause of woman suffrage. She attended the first meet- ing of the national association, held in Rochester in 1848, and was, according Her Identification With the to Miss Anthony, one of the leading Abolition Cause, the Woman spirits in that notable gathering. From Suffrage Movement, and "With that time down to the international woman suffrage convention held in SpiriUialism—Mortuary Record. Washington in March, 1888, which she Mrs. Amy Kirby Post died last even- also attended, she was always a leader ing at her residence, 56 Sophia street, in that band of famous women who aged 86 years. -

Shaw Memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1900 Art in the Classroom National Gallery of Art, Washington Getting to Know the Soldiers 1 2

national gallery of art The Shaw Memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1900 Art in the Classroom National Gallery of Art, Washington Getting to Know the Soldiers 1 2 Every work of art has many stories to tell. The Shaw Memorial tells of the bravery and commitment Take a Look Perspective-Taking through Writing shown by a young American leader and his newly recruited soldiers as they departed to fight for a Take a quiet minute to look carefully at the Imagine yourself a soldier in the 54th Massachusetts. free and united nation. This monumental sculpture also gives us a lens to see the choices of an artist Shaw Memorial. Choose a key moment in the soldier’s life — marching from Boston Common, approaching the battlefield at who aimed to memorialize a pivotal moment in the American Civil War (1862 – 1865). What do you see? Share words or phrases that Fort Wagner, or seeing the Shaw Memorial for the first President Abraham Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, describe any aspect of the work. time. What are you thinking or feeling at this moment? Write an “I Am” poem. declaring slaves in the South to be free and allowing African Americans to join the Union army. Include as many details as you can, listing what “I Am” Poem Shortly after this, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the first African American troop in the you observe with your eyes. North, began recruiting soldiers to enlist. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, a twenty-five-year-old officer 1. by from a noted abolitionist family, was chosen to lead the regiment. -

Yancy 1 the Idolization of Colonel Robert G. Shaw

Yancy 1 The Idolization of Colonel Robert G. Shaw “I have changed my mind about the black regiment” (Shaw, 8 Feb. 1863). With these nine words to his future wife on February 8, 1863, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw changed the way in which history viewed him forever. Wanting to “prove that a negro can be made a good soldier” (Shaw, 8 Feb. 1863), Shaw took control of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the first all black regiment (save for its officers) in America. He is hailed as a hero for his bravery and courage, not only because he is seen as one of the vital abolitionists who enabled black men to fight in the Civil War, but also for his martyr-like death at Fort Wagner, South Carolina. Shaw never fails to be acknowledged when the 54th is discussed, and yet his soldiers remain in the background of history. While Colonel Robert G. Shaw exhibited tremendous leadership and courage, historical accounts excessively exalt him by overlooking his reluctance to lead, ignoring his prejudices, honoring his heroics over his soldiers’, and inaccurately portraying him in Glory. Although Shaw is hailed as “the most abolitionist hero of the war” (Where Death and Glory Meet xiv), he actually rejected the leadership position for the 54th at first. As he wrote in one of his letters, had he accepted the offer, it would “only have been from a sense of duty; for it would have been anything but an agreeable task” (Shaw, 4 Feb. 1863). The ‘sense of duty’ Shaw was most likely referring to was his parents, as both were abolitionists. -

KINSLEY, Edward

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Manuscript Division Finding Aids Finding Aids 10-1-2015 KINSLEY, Edward MSRC Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu Recommended Citation Staff, MSRC, "KINSLEY, Edward" (2015). Manuscript Division Finding Aids. 116. https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu/116 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscript Division Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edward W. Kinsley Papers Collection 143-1 Prepared by: Joellen El-Bashir November 1986 Manuscript Division Scope Note The papers of Edward W. Kinsley (b. 1830 - d.?). Abolitionist, merchant, investor, and an agent for the state of Massachusetts, cover a period of approximately four years, from 1862 to 1865, when the Civil War was at its height. Kinsley, as a state agent and member of the committee which had been formed by the governor to recruit and fund the Massachusetts "Colored" Volunteers, was apparently one of those instrumental in supplying the black regiments as well as the white volunteer regiments. The papers were donated to Moorland-Spingarn in 1974 by Dr. John W. Blassingame, noted historian and author. The collection totals approximately « linear foot and consists primarily of correspondence. There are also official passes issued to Kinsley when he visited the camps of the Massachusetts volunteer regiments, receipts related to equipment purchase, and announcements relative to Kinsley's mercantile partnership. The correspondence reflects Kinsley's political connections and his ability and willingness to grant favors, probably a result of his friendship with the governor of Massachusetts, John A. -

Saint-Gaudens' Shaw Memorial

Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-fourth Regiment National Gallery of Art The Shaw Memorial Project is made possible by the generous support of The Circle of the National Gallery of Art 1 On July 18, 1863, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw The Sculptor was killed while leading the Massachusetts Born March 1, 1848, Augustus Saint-Gaudens Fifty-fourth Volun teer Infantry in a bloody (fig. 2) was brought to the United States assault on Fort Wagner, near Charleston, from Ireland as an infant. His mother, Mary South Carolina. Although nearly half of the McGuinness, and his father, Bernard Saint- regiment fell and was badly defeated, the Gaudens, a French man, settled in New York battle proved to be an event of poignant where Bernard began a shoemaking busi- and powerful symbolic significance, as ness. At thirteen Saint-Gaudens received his the Massachusetts Fifty-fourth was one first training in sculpture in the workshop of the first African-American units of the of a French-born cameo-cutter, and he later Civil War. It would take nearly thirty-four attended drawing classes at the Cooper years of public concern and more than a Union School and the National Academy decade of devotion by America’s foremost of Design. sculptor to create a fitting memorial to In 1867 Saint-Gaudens went to Paris, the sacrifice of these brave men (fig. 1). where he supported himself by making The result is the finest achievement of cameos and copies of famous sculpture. Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ career, and He enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts arguably the greatest American sculpture and, in museums, was exposed for the first of the nineteenth century.