Illustrations by AD CAMERON Consultant Editor DR. C.J.O. HARRISON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Limits in Some Philippine Birds Including the Greater Flameback Chrysocolaptes Lucidus

FORKTAIL 27 (2011): 29–38 Species limits in some Philippine birds including the Greater Flameback Chrysocolaptes lucidus N. J. COLLAR Philippine bird taxonomy is relatively conservative and in need of re-examination. A number of well-marked subspecies were selected and subjected to a simple system of scoring (Tobias et al. 2010 Ibis 152: 724–746) that grades morphological and vocal differences between allopatric taxa (exceptional character 4, major 3, medium 2, minor 1; minimum score 7 for species status). This results in the recognition or confirmation of species status for (inverted commas where a new English name is proposed) ‘Philippine Collared Dove’ Streptopelia (bitorquatus) dusumieri, ‘Philippine Green Pigeon’ Treron (pompadora) axillaris and ‘Buru Green Pigeon’ T. (p.) aromatica, Luzon Racquet-tail Prioniturus montanus, Mindanao Racquet-tail P. waterstradti, Blue-winged Raquet-tail P. verticalis, Blue-headed Raquet-tail P. platenae, Yellow-breasted Racquet-tail P. flavicans, White-throated Kingfisher Halcyon (smyrnensis) gularis (with White-breasted Kingfisher applying to H. smyrnensis), ‘Northern Silvery Kingfisher’ Alcedo (argentata) flumenicola, ‘Rufous-crowned Bee-eater’ Merops (viridis) americanus, ‘Spot-throated Flameback’ Dinopium (javense) everetti, ‘Luzon Flameback’ Chrysocolaptes (lucidus) haematribon, ‘Buff-spotted Flameback’ C. (l.) lucidus, ‘Yellow-faced Flameback’ C. (l.) xanthocephalus, ‘Red-headed Flameback’ C. (l.) erythrocephalus, ‘Javan Flameback’ C. (l.) strictus, Greater Flameback C. (l.) guttacristatus, ‘Sri Lankan Flameback’ (Crimson-backed Flameback) Chrysocolaptes (l.) stricklandi, ‘Southern Sooty Woodpecker’ Mulleripicus (funebris) fuliginosus, Visayan Wattled Broadbill Eurylaimus (steerii) samarensis, White-lored Oriole Oriolus (steerii) albiloris, Tablas Drongo Dicrurus (hottentottus) menagei, Grand or Long-billed Rhabdornis Rhabdornis (inornatus) grandis, ‘Visayan Rhabdornis’ Rhabdornis (i.) rabori, and ‘Visayan Shama’ Copsychus (luzoniensis) superciliaris. -

Structure and Condition of Zambezi Valley Dry Forests and Thickets

SSTTRRUUCCTTUURREE AANNDD CCOONNDDIITTIIOONN OOFF ZZAAMMBBEEZZII VVAALLLLEEYY DDRRYY FFOORREESSTTSS AANNDD TTHHIICCKKEETTSS January 2002 Published by The Zambezi Society STRUCTURE AND CONDITION OF ZAMBEZI VALLEY DRY FORESTS AND THICKETS by R.E. Hoare, E.F. Robertson & K.M. Dunham January 2002 Published by The Zambezi Society The Zambezi Society is a non- The Zambezi Society P O Box HG774 governmental membership Highlands agency devoted to the Harare conservation of biodiversity Zimbabwe and wilderness and the Tel: (+263-4) 747002/3/4/5 sustainable use of natural E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.zamsoc.org resources in the Zambezi Basin Zambezi Valley dry forest biodiversity i This report has a series of complex relationships with other work carried out by The Zambezi Society. Firstly, it forms an important part of the research carried out by the Society in connection with the management of elephants and their habitats in the Guruve and Muzarabani districts of Zimbabwe, and the Magoe district of Mozambique. It therefore has implications, not only for natural resource management in these districts, but also for the transboundary management of these resources. Secondly, it relates closely to the work being carried out by the Society and the Biodiversity Foundation for Africa on the identification of community-based mechanisms FOREWORD for the conservation of biodiversity in settled lands. Thirdly, it represents a critically important contribution to the Zambezi Basin Initiative for Biodiversity Conservation (ZBI), a collaboration between the Society, the Biodiversity Foundation for Africa, and Fauna & Flora International. The ZBI is founded on the acquisition and dissemination of good biodiversity information for incorporation into developmental and other planning initiatives. -

Borneo: Broadbills & Bristleheads

TROPICAL BIRDING Trip Report: BORNEO June-July 2012 A Tropical Birding Set Departure Tour BORNEO: BROADBILLS & BRISTLEHEADS RHINOCEROS HORNBILL: The big winner of the BIRD OF THE TRIP; with views like this, it’s easy to understand why! 24 June – 9 July 2012 Tour Leader: Sam Woods All but one photo (of the Black-and-yellow Broadbill) were taken by Sam Woods (see http://www.pbase.com/samwoods or his blog, LOST in BIRDING http://www.samwoodsbirding.blogspot.com for more of Sam’s photos) 1 www.tropicalbirding.com Tel: +1-409-515-0514 E-mail: [email protected] TROPICAL BIRDING Trip Report: BORNEO June-July 2012 INTRODUCTION Whichever way you look at it, this year’s tour of Borneo was a resounding success: 297 bird species were recorded, including 45 endemics . We saw all but a few of the endemic birds we were seeking (and the ones missed are mostly rarely seen), and had good weather throughout, with little rain hampering proceedings for any significant length of time. Among the avian highlights were five pitta species seen, with the Blue-banded, Blue-headed, and Black-and-crimson Pittas in particular putting on fantastic shows for all birders present. The Blue-banded was so spectacular it was an obvious shoe-in for one of the top trip birds of the tour from the moment we walked away. Amazingly, despite absolutely stunning views of a male Blue-headed Pitta showing his shimmering cerulean blue cap and deep purple underside to spectacular effect, he never even got a mention in the final highlights of the tour, which completely baffled me; he simply could not have been seen better, and birds simply cannot look any better! However, to mention only the endemics is to miss the mark, as some of the, other, less local birds create as much of a stir, and can bring with them as much fanfare. -

Fulica Cornuta Bonaparte 1853 Nombre Común: Tagua Cornuda; Polla De Agua; Pato Negro; Gallina; Soca; Horned Coot (Inglés), Wari (Kunza)

FICHA DE ANTECEDENTES DE ESPECIE Id especie: Nombre Científico: Fulica cornuta Bonaparte 1853 Nombre Común: tagua cornuda; polla de agua; pato negro; gallina; soca; Horned Coot (inglés), Wari (kunza) Reino: Animalia Orden: Gruiformes Phyllum/Divis ión: Chordata Familia: Rallidae Clase: Aves Género: Fulica Sinonimia: Sin sinonimia Nota Taxonómica: Antecedentes Generales: ASPECTOS MORFOLÓGICOS: La tagua cornuda tiene el cuerpo rechoncho, de color uniformemente negruzco en ambos sexos, con la cabeza, cuello y hasta la espalda algo más oscura, y más gris apizarrada en la cara ventral del cuerpo. Los juveniles son en general más claros, sin negro en la cabeza y presentan una mancha blanca en el mentón y garganta. En el adulto el pico es fuerte y de color amarillo anaranjado, con una mancha negra en el culmen; en tanto que en los juveniles, el pico es negro verdoso con ligero tinte café. Las piernas en adultos y juveniles son de color verdoso, tirando al café con tinte gris oscuro a nivel de las articulaciones. Los dedos lobulados y provistos de poderosas uñas, son de gran tamaño, llegando a medir entre 20 y 30 cm de largo el dedo mayor. Los pies de los machos son apreciablemente más grandes que las de las hembras (Goodall et al. 1964, Araya et al. 1998, Martínez & González 2004, Jaramillo 2005). En los polluelos las piernas son negras, pero el pico es rosado con punta negra y amarilla y el cuerpo cubierto de un plumón fino y completamente negro, a excepción de una pequeña zona de plumillas blanquecinas en el mentón. El iris en el polluelo y en el ave juvenil es de color café, cambiando progresivamente mientras avanza a la adultez, hasta adquirir el característico color café anaranjado (Goodall et al. -

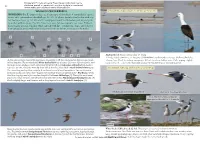

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-Eaters, Babblers, and a Whole Lot More

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-eaters, Babblers, and a whole lot more A Tropical Birding Set Departure July 1-16, 2018 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos by Ken Behrens TOUR SUMMARY Borneo lies in one of the biologically richest areas on Earth – the Asian equivalent of Costa Rica or Ecuador. It holds many widespread Asian birds, plus a diverse set of birds that are restricted to the Sunda region (southern Thailand, peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo), and dozens of its own endemic birds and mammals. For family listing birders, the Bornean Bristlehead, which makes up its own family, and is endemic to the island, is the top target. For most other visitors, Orangutan, the only great ape found in Asia, is the creature that they most want to see. But those two species just hint at the wonders held by this mysterious island, which is rich in bulbuls, babblers, treeshrews, squirrels, kingfishers, hornbills, pittas, and much more. Although there has been rampant environmental destruction on Borneo, mainly due to the creation of oil palm plantations, there are still extensive forested areas left, and the Malaysian state of Sabah, at the northern end of the island, seems to be trying hard to preserve its biological heritage. Ecotourism is a big part of this conservation effort, and Sabah has developed an excellent tourist infrastructure, with comfortable lodges, efficient transport companies, many protected areas, and decent roads and airports. So with good infrastructure, and remarkable biological diversity, including many marquee species like Orangutan, several pittas and a whole Borneo: Bristleheads and Broadbills July 1-16, 2018 range of hornbills, Sabah stands out as one of the most attractive destinations on Earth for a travelling birder or naturalist. -

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories Compiled by S. Oldfield Edited by D. Procter and L.V. Fleming ISBN: 1 86107 502 2 © Copyright Joint Nature Conservation Committee 1999 Illustrations and layout by Barry Larking Cover design Tracey Weeks Printed by CLE Citation. Procter, D., & Fleming, L.V., eds. 1999. Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Disclaimer: reference to legislation and convention texts in this document are correct to the best of our knowledge but must not be taken to infer definitive legal obligation. Cover photographs Front cover: Top right: Southern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome (Richard White/JNCC). The world’s largest concentrations of southern rockhopper penguin are found on the Falkland Islands. Centre left: Down Rope, Pitcairn Island, South Pacific (Deborah Procter/JNCC). The introduced rat population of Pitcairn Island has successfully been eradicated in a programme funded by the UK Government. Centre right: Male Anegada rock iguana Cyclura pinguis (Glen Gerber/FFI). The Anegada rock iguana has been the subject of a successful breeding and re-introduction programme funded by FCO and FFI in collaboration with the National Parks Trust of the British Virgin Islands. Back cover: Black-browed albatross Diomedea melanophris (Richard White/JNCC). Of the global breeding population of black-browed albatross, 80 % is found on the Falkland Islands and 10% on South Georgia. Background image on front and back cover: Shoal of fish (Charles Sheppard/Warwick -

Report on Biodiversity and Tropical Forests in Indonesia

Report on Biodiversity and Tropical Forests in Indonesia Submitted in accordance with Foreign Assistance Act Sections 118/119 February 20, 2004 Prepared for USAID/Indonesia Jl. Medan Merdeka Selatan No. 3-5 Jakarta 10110 Indonesia Prepared by Steve Rhee, M.E.Sc. Darrell Kitchener, Ph.D. Tim Brown, Ph.D. Reed Merrill, M.Sc. Russ Dilts, Ph.D. Stacey Tighe, Ph.D. Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................. i List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. v List of Figures............................................................................................................................... vii Acronyms....................................................................................................................................... ix Executive Summary.................................................................................................................... xvii 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................1- 1 2. Legislative and Institutional Structure Affecting Biological Resources...............................2 - 1 2.1 Government of Indonesia................................................................................................2 - 2 2.1.1 Legislative Basis for Protection and Management of Biodiversity and -

Thailand Highlights 14Th to 26Th November 2019 (13 Days)

Thailand Highlights 14th to 26th November 2019 (13 days) Trip Report Siamese Fireback by Forrest Rowland Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Forrest Rowland Trip Report – RBL Thailand - Highlights 2019 2 Tour Summary Thailand has been known as a top tourist destination for quite some time. Foreigners and Ex-pats flock there for the beautiful scenery, great infrastructure, and delicious cuisine among other cultural aspects. For birders, it has recently caught up to big names like Borneo and Malaysia, in terms of respect for the avian delights it holds for visitors. Our twelve-day Highlights Tour to Thailand set out to sample a bit of the best of every major habitat type in the country, with a slight focus on the lush montane forests that hold most of the country’s specialty bird species. The tour began in Bangkok, a bustling metropolis of winding narrow roads, flyovers, towering apartment buildings, and seemingly endless people. Despite the density and throng of humanity, many of the participants on the tour were able to enjoy a Crested Goshawk flight by Forrest Rowland lovely day’s visit to the Grand Palace and historic center of Bangkok, including a fun boat ride passing by several temples. A few early arrivals also had time to bird some of the urban park settings, even picking up a species or two we did not see on the Main Tour. For most, the tour began in earnest on November 15th, with our day tour of the salt pans, mudflats, wetlands, and mangroves of the famed Pak Thale Shore bird Project, and Laem Phak Bia mangroves. -

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: the role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity edited by A. J. Hails Ramsar Convention Bureau Ministry of Environment and Forest, India 1996 [1997] Published by the Ramsar Convention Bureau, Gland, Switzerland, with the support of: • the General Directorate of Natural Resources and Environment, Ministry of the Walloon Region, Belgium • the Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark • the National Forest and Nature Agency, Ministry of the Environment and Energy, Denmark • the Ministry of Environment and Forests, India • the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Sweden Copyright © Ramsar Convention Bureau, 1997. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior perinission from the copyright holder, providing that full acknowledgement is given. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. The views of the authors expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of the Ramsar Convention Bureau or of the Ministry of the Environment of India. Note: the designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Ranasar Convention Bureau concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: Halls, A.J. (ed.), 1997. Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: The Role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity. -

TNP SOK 2011 Internet

GARDEN ROUTE NATIONAL PARK : THE TSITSIKAMMA SANP ARKS SECTION STATE OF KNOWLEDGE Contributors: N. Hanekom 1, R.M. Randall 1, D. Bower, A. Riley 2 and N. Kruger 1 1 SANParks Scientific Services, Garden Route (Rondevlei Office), PO Box 176, Sedgefield, 6573 2 Knysna National Lakes Area, P.O. Box 314, Knysna, 6570 Most recent update: 10 May 2012 Disclaimer This report has been produced by SANParks to summarise information available on a specific conservation area. Production of the report, in either hard copy or electronic format, does not signify that: the referenced information necessarily reflect the views and policies of SANParks; the referenced information is either correct or accurate; SANParks retains copies of the referenced documents; SANParks will provide second parties with copies of the referenced documents. This standpoint has the premise that (i) reproduction of copywrited material is illegal, (ii) copying of unpublished reports and data produced by an external scientist without the author’s permission is unethical, and (iii) dissemination of unreviewed data or draft documentation is potentially misleading and hence illogical. This report should be cited as: Hanekom N., Randall R.M., Bower, D., Riley, A. & Kruger, N. 2012. Garden Route National Park: The Tsitsikamma Section – State of Knowledge. South African National Parks. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................2 2. ACCOUNT OF AREA........................................................................................................2 -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird.