Chapter 7 Party Alignments. Change and Continuity Herbert Kitschelt and Philipp Rehm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

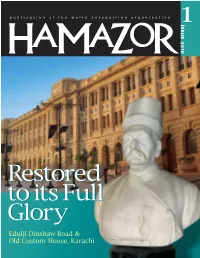

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Antisemitism in the Radical Left and the British Labour Party, by Dave Rich

Kantor Center Position Papers Editor: Mikael Shainkman January 2018 ANTISEMITISM IN THE RADICAL LEFT AND THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY Dave Rich* Executive Summary Antisemitism has become a national political issue and a headline story in Britain for the first time in decades because of ongoing problems in the Labour Party. Labour used to enjoy widespread Jewish support but increasing left wing hostility towards Israel and Zionism, and a failure to understand and properly oppose contemporary antisemitism, has placed increasing distance between the party and the UK Jewish community. This has emerged under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, a product of the radical 1960s New Left that sees Israel as an apartheid state created by colonialism, but it has been building on the fringes of the left for decades. Since Corbyn became party leader, numerous examples of antisemitic remarks made by Labour members, activists and elected officials have come to light. These remarks range from opposition to Israel’s existence or claims that Zionism collaborated with Nazism, to conspiracy theories about the Rothschilds or ISIS. The party has tried to tackle the problem of antisemitism through procedural means and generic declarations opposing antisemitism, but it appears incapable of addressing the political culture that produces this antisemitism: possibly because this radical political culture, borne of anti-war protests and allied to Islamist movements, is precisely where Jeremy Corbyn and his closest associates find their political home. A Crisis of Antisemitism Since early 2016, antisemitism has become a national political issue in Britain for the first time in decades. This hasn’t come about because of a surge in support for the far right, or jihadist terrorism against Jews. -

Party Polarization and Campaign Finance

July 2014 Party Polarization and Campaign Finance Thomas E. Mann and Anthony Corrado INTRODUCTION he intense debate these days about the shortcomings of American democ- racy and how best to deal with them often features assertions about parties, Tpolarization, and campaign finance that appear puzzling if not downright con- Thomas E. Mann tradictory. For example, some analysts argue that campaign finance reforms have is the W. Averell Harriman reduced the role of political parties in campaigns and thereby weakened the ability Chair and senior fellow in 1 Governance Studies at The of party leaders to commandeer their members on behalf of achievable policy goals. Brookings Institution. Between 1987 and 1999, he was Director This seems an odd argument to make in an era of historically high levels of party loy- of Governmental Studies at alty—on roll calls in Congress and voting in the electorate. Are parties too strong and Brookings. He is co-author, with Norman J. Ornstein, of It's Even unified or too weak and fragmented? Have they been marginalized in the financing of Worse Than It Looks: How the elections or is their role at least as strong as it has ever been? Does the party role in American Constitutional System Collided With the New Politics of campaign finance (weak or strong) materially shape our capacity to govern? Extremism. A second example involves the mix of small and large individual donors and its connection to polarization. The increasing involvement in presidential and congressional campaigns of large donors—especially through Super PACs and politically-active nonprofit organizations—has raised serious concerns about whether the super-wealthy are buying American democracy. -

Initiating, Planning and Managing Coalitions

INITIATING, PLANNING AND MANAGING COALITIONS AN AFRICAN LIBERAL PERSPECTIVE HANDBOOK INITIATING, PLANNING AND MANAGING COALITIONS CONTRIBUTORS Gilles Bassindikila Justin Nzoloufoua Lucrèce Nguedi Leon Schreiber Solly Msimanga Helen Zille Lotfi Amine Hachemi Assoumane Kamal Soulé Madonna Kumbu Kumbel Serge Mvukulu Bweya-Nkiama Tolerance Itumeleng Lucky Daniel Tshireletso Maître Boutaina Benmallam Richard Nii Amarh Nana Ofori Owusu Mutale Nalumango Dr Choolwe Beyani PUBLICATION COORDINATOR Nangamso Kwinana TRANSLATION Mathieu Burnier & Marvin Mncwabe at LoluLwazi Business Support DESIGN Vernon Kallis at LoluLwazi Business Support EDITORS Iain Gill Gijs Houben Martine Van Schoor Daniëlle Brouwer Masechaba Mdaka Nangamso Kwinana For further information and distribution Africa Liberal Network 3rd Floor Travel House, 6 Hood Avenue Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196 The Republic of South Africa Direct: +27 87 806 2676 Telephone: +27 11 880 8851 Mobile: +27 73 707 8513 CONTRIBUTORS [email protected] www.africaliberalnetwork.org 2 3 INITIATING, PLANNING AND MANAGING COALITIONS AN AFRICAN LIBERAL PERSPECTIVE HANDBOOK A Word from our President 4 CONTENTS 5 Our Executive Committee 7 About the Author 8 Introduction 10 Methodology 12 Foreward 15 In Memoriam 16 Initiating - The Pre-Election Phase 30 Planning - Pre-Coalition Phase 38 Managing - The Governing Phase 3 INITIATING, PLANNING AND MANAGING COALITIONS Dear reader, We are delighted and proud to share with you, this publication relating to initiating, planning and managing coalitions. -

LORD BOLINGBROKE's THEORY of PARTY and OPPOSITION1 By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository Max Skjönsberg, HJ, Oct 2015 LORD BOLINGBROKE’S THEORY OF PARTY AND OPPOSITION1 By MAX SKJÖNSBERG, London School of Economics and Political Science Abstract: Bolingbroke has been overlooked by intellectual historians in the last few decades, at least in comparison with ‘canonical’ thinkers. This article examines one of the most important but disputable aspects of his political thought: his views on political parties and his theory of opposition. It aims to demonstrate that Bolingbroke’s views on party have been misunderstood and that it is possible to think of him as an advocate of political parties rather than the ‘anti-party’ writer he is commonly known as. It has been suggested that Bolingbroke prescribed a state without political parties. By contrast, this article seeks to show that Bolingbroke was in fact the promoter of a very specific party, a systematic parliamentary opposition party in resistance to what he perceived as the Court Whig faction in power. It will 1 I have benefited from comments by Adrian Blau, Tim Hochstrasser, Paul Keenan, Robin Mills, and Paul Stock, as well as conversations with J. C. D. Clark, Richard Bourke, and Quentin Skinner at various stages of this project. As usual, however, the buck stops with the writer. I presented an earlier and shorter version of this article at the inaugural Early-Modern Intellectual History Postgraduate Conference at Newcastle University in June 2015. Eighteenth-century spelling has been kept in quotations throughout as have inconsistencies in spelling. -

Lesson Plan with Activities: Political

LESSON PLAN POLITICAL PARTIES Recommended for Grade 10 Duration: Approximately 60 minutes BACKGROUND INFORMATION Parliamentary Roles: www.ola.org/en/visit-learn/about-ontarios-parliament/ parliamentary-roles LEARNING GOALS This lesson plan is designed to engage students in the political process through participatory activities and a discussion about the various political parties. Students will learn the differences between the major parties of Ontario and how they connect with voters, and gain an understanding of the important elements of partisan politics. INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION (10 minutes) Canada is a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy, founded on the rule of law and respect for rights and freedoms. Ask students which country our system of government is based on. Canada’s parliamentary system stems from the British, or “Westminster,” tradition. Since Canada is a federal state, responsibility for lawmaking is shared among one federal, ten provincial and three territorial governments. Canada shares the same parliamentary system and similar roles as other parliaments in the Commonwealth – countries with historic links to Britain. In our parliament, the Chamber is where our laws are debated and created. There are some important figures who help with this process. Some are partisan and some are non-partisan. What does it mean to be partisan/non-partisan? Who would be voicing their opinions in the Chamber? A helpful analogy is to imagine the Chamber as a game of hockey, where the political parties are the teams playing and the non-partisan roles as the people who make sure the game can happen (ex. referees, announcers, score keepers, etc.) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF ONTARIO POLITICAL PARTIES 01 EXPLANATION (5 minutes) Political Parties: • A political party is a group of people who share the same political beliefs. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

From Privy Council to Supreme Court: a Rite of Passage for New Zealand’S Legal System

THE HARKNESS HENRY LECTURE FROM PRIVY COUNCIL TO SUPREME COURT: A RITE OF PASSAGE FOR NEW ZEALAND’S LEGAL SYSTEM BY PROFESSOR MARGARET WILSON* I. INTRODUCTION May I first thank Harkness Henry for the invitation to deliver the 2010 Lecture. It gives me an opportunity to pay a special tribute to the firm for their support for the Waikato Law Faculty that has endured over the 20 years life of the Faculty. The relationship between academia and the profession is a special and important one. It is essential to the delivery of quality legal services to our community but also to the maintenance of the rule of law. Harkness Henry has also employed many of the fine Waikato law graduates who continue to practice their legal skills and provide leadership in the profession, including the Hamilton Women Lawyers Association that hosted a very enjoyable dinner in July. I have decided this evening to talk about my experience as Attorney General in the establish- ment of New Zealand’s new Supreme Court, which is now in its fifth year. In New Zealand, the Attorney General is a Member of the Cabinet and advises the Cabinet on legal matters. The Solici- tor General, who is the head of the Crown Law Office and chief legal official, is responsible for advising the Attorney General. It is in matters of what I would term legal policy that the Attorney General’s advice is normally sought although Cabinet also requires legal opinions from time to time. The other important role of the Attorney General is to advise the Governor General on the appointment of judges in all jurisdictions except the Mäori Land Court, where the appointment is made by the Minister of Mäori Affairs in consultation with the Attorney General. -

Throughout the 1950S the Liberal Party of South Africa Suffered Severe Internal Conflict Over Basic Issues of Policy and Strategy

Throughout the 1950s the Liberal Party of South Africa suffered severe internal conflict over basic issues of policy and strategy. On one level this stemmed from the internal dynamics of a small party unequally divided between the Cape, Transvaal and Natal, in terms of membership, racial composftion and political traditon. This paper and the larger work from which it is taken , however, argue inter alia that the conflict stemmed to a greater degree from a more fundamental problem, namely differing interpretations of liberalism and thus of the role of South African liberals held by various elements within the Liberal Party (LP). This paper analyses the political creed of those parliamentary and other liberals who became the early leaders of the LP. Their standpoint developed in specific circumstances during the period 1947-1950, and reflected opposition to increasingly radical black political opinion and activity, and retreat before the unfolding of apartheid after 1948. This particular brand of liberalism was marked by a rejection of extra- parliamentary activity, by a complete rejection of the univensal franchise, and by anti-communism - the negative cgaracteristics of the early LP, but also the areas of most conflict within the party. The liberals under study - including the Ballingers, Donald Molteno, Leo Marquard, and others - were all prominent figures. All became early leaders of the Liberal Party in 1953, but had to be *Ihijackedffigto the LP by having their names published in advance of the party being launched. The strategic prejudices of a small group of parliamentarians, developed in the 1940s, were thus to a large degree grafted on to non-racial opposition politics in the 1950s through an alliance with a younger generation of anti-Nationalists in the LP. -

What Is Neo-Liberalism? Justifications of Deregulating Financial Markets in Norway and Finland © SIFO 2015 Project Note No 6 – 2015

Project note no 6-2015 Pekka Sulkunen What is Neo-liberalism? Justifications of deregulating financial markets in Norway and Finland © SIFO 2015 Project Note no 6 – 2015 NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH Sandakerveien 24 C, Building B P.O. Box 4682 Nydalen N-0405 Oslo www.sifo.no Due to copyright restrictions, this report is not to be copied from or distributed for any purpose without a special agreement with SIFO. Reports made available on the www.sifo.no site are for personal use only. Copyright infringement will lead to a claim for compensation. Prosjektrapport nr.6 - 2015 Tittel Antall sider Dato 48 27.10.2015 Title ISBN ISSN What is Neo-liberalism? Justifications of deregulating financial markets in Norway and Finland Forfatter(e) Prosjektnummer Faglig ansvarlig sign. Pekka Sulkunen 11201014 Oppdragsgiver Norges Forskningsråd Sammendrag Rapporten dokumenter at dereguleringen av den norske og finske økonomien først og fremst handlet om politikk og politiske prosesser, og i liten grad begrunnet i økonomisk teori. Heller ikke neoliberal filosofi slik vi kjenner den fra USA og Storbritannia spilte noen stor rolle i de to landene. Isteden handlet det om forestillingen om, og fremveksten av, en ny type velferdsstat med behov for en moralsk legitimering av autonomi. Summary The report documents that the deregulation of the Norwegian and Finnish economy primarily was about politics and political processes, and to a much lesser extent about justifications rooted in economic theory. Nor neoliberal philosophy as we know it from the US and Britain played a major role in the two countries. Instead, it was about the notion, and the emergence of, a new kind of welfare state in need of a moral legitimization of autonomy. -

Dimensions and Alignments in European Union Politics: Cognitive Constraints and Partisan Responses

Working Paper Series in European Studies Volume 1, Number 3 Dimensions and Alignments in European Union Politics: Cognitive Constraints and Partisan Responses DR. SIMON HIX DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE United Kingdom ([email protected]) EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE: GILLES BOUSQUET KEITH COHEN COLLEEN DUNLAVY ANDREAS KAZAMIAS LEON LINDBERG ELAINE MARKS ANNE MINER ROBERT OSTERGREN MARK POLLACK GREGORY SHAFFER MARC SILBERMAN JONATHAN ZEITLIN Copyright © 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author. European Studies Program, International Institute, University of Wisconsin--Madison Madison, Wisconsin http://polyglot.lss.wisc.edu/eur/ 1 Dimensions and Alignments in European Union Politics: Cognitive Constraints and Partisan Responses Simon Hix Department of Government, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, United Kingdom Abstract As the European Union (EU) has evolved, the study agenda has shifted from ‘European integration’ to ‘EU politics’. Missing from this new agenda, however, is an understanding of the ‘cognitive constraints’ on actors, and how actors respond: i.e. the shape of the EU ‘political space’ and the location of social groups and competition between actors within this space. The article develops a theoretical framework for understanding the shape of the EU political space (the interaction between an Integration-Independence and a Left-Right dimension and the location of class and sectoral groups within this map), and tests this framework on the policy positions of the Socialist, Christian Democrat and Liberal party leaders between 1976 and 1994 (using the techniques of the ECPR Party Manifestos Group Project). -

DO AS the SPANIARDS DO. the 1821 PIEDMONT INSURRECTION and the BIRTH of CONSTITUTIONALISM Haced Como Los Españoles. Los Movimi

DO AS THE SPANIARDS DO. THE 1821 PIEDMONT INSURRECTION AND THE BIRTH OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Haced como los españoles. Los movimientos de 1821 en Piamonte y el origen del constitucionalismo PIERANGELO GENTILE Universidad de Turín [email protected] Cómo citar/Citation Gentile, P. (2021). Do as the Spaniards do. The 1821 Piedmont insurrection and the birth of constitutionalism. Historia y Política, 45, 23-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.18042/hp.45.02 (Reception: 15/01/2020; review: 19/04/2020; acceptance: 19/09/2020; publication: 01/06/2021) Abstract Despite the local reference historiography, the 1821 Piedmont insurrection still lacks a reading that gives due weight to the historical-constitutional aspect. When Carlo Alberto, the “revolutionary” Prince of Carignano, granted the Cádiz Consti- tution, after the abdication of Vittorio Emanuele I, a crisis began in the secular history of the dynasty and the kingdom of Sardinia: for the first time freedoms and rights of representation broke the direct pledge of allegiance, tipycal of the absolute state, between kings and people. The new political system was not autochthonous but looked to that of Spain, among the many possible models. Using the extensive available bibliography, I analyzed the national and international influences of that 24 PIERANGELO GENTILE short historical season. Moreover I emphasized the social and geographic origin of the leaders of the insurrection (i.e. nobility and bourgeoisie, core and periphery of the State) and the consequences of their actions. Even if the insurrection was brought down by the convergence of the royalist forces and the Austrian army, its legacy weighed on the dynasty.