Julia Rebekka Adler Has Been Playing Viola Since She Was Barely Big Enough to Manage an Instrument of Its Size

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty Recital: Mozart/Shostakovich III Susan Waterbury

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-25-2006 Faculty Recital: Mozart/Shostakovich III Susan Waterbury Debra Moree Elizabeth Simkin Jennifer Hayghe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Waterbury, Susan; Moree, Debra; Simkin, Elizabeth; and Hayghe, Jennifer, "Faculty Recital: Mozart/Shostakovich III" (2006). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5058. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5058 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC FACULTY RECITAL MOZART/SHOSTAKOVICH III An evening of chamber music celebrating the 250th birth anniversary of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) and the 100th birth anniversary of Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Susan Waterbury, violin Debra Moree, viola Elizabeth Simkin, cello Jennifer Hayghe, piano Hockett Family Recital Hall Monday, September 25, 2006 7:00 p.m. ITHACA I PROGRAM Piano Sonata No. 18 in D Major, Wolfgang Amadeus :Mozart K576 (1789) (1756-1791) Allegro Adagio Allegretto Sonata for Viola & Piano, Op. 147 (1975) Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Moderato Allegretto Adagio INTERMISSION Trio for Violin, Cello & Piano, Dmitri Shostakovich No. 2 in e minor, Op. 67 (1944) Andante Allegro non troppo Largo Allegretto Program Notes Mozart and Shostakovitch III The pairing of Mozart and Shostakovich, born 150 years apart, is more natural than e might initially suspect. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756- 5 cember 1791), the seventh and last child born to Leopold Mozart and his wife Maria Anna, is the most famous musical prodigy in history. -

Numerical Listing

SEQ DISC NO LABEL CDN PRICE PERFORMER DESCRIPTION a a THREE FOR TWO! ON ALL ITEMS PRICED AT £5.00, ONE- THIRD (1/3) OFF ALL ORDERS FOR 3 OR MORE a a 23776 0 10 1441-3 Supraphon, blue m A1 £10.00 Talich, Vaclav Vol. 1. Suk: Serenade for Strings; Asrael; Ripening. Czech PO c 22047 1 11 1106 Supraphon s A1 £5.00 Vlach SQ Beethoven: Quartets, Opp.18-1; 18-6 bb 22524 1 11 1755 Supraphon s A1 £5.00 Prague SQ Lubomir Zelezny: Clt. Quintet; Wind Quintet; Piano Trio. Prague Wind Quintet, Smetana Trio bb 23786 10 Penzance, USA m A1 £8.00 Callas, Maria, s Wagner: Parsifal, Act 2. Baldelli, Modesti, Pagliughi, -Gui. Live, 20.xi.50. In Italian a 22789 1007831 VdsM, References m A1 £7.00 Kreisler, Fritz, vn Beethoven; Sonatas 5, "Spring"; 9, "Kreutzer". F. Rupp, pf bb 23610 101 Rara Avis, lacquer m A-1- £10.00 Ginsburg, Grigory, pf Liszt: Bells of Geneva, Campanella, Rigoletto, Spanish Rhapsody / Weber: Rondo brillante / Chopin: Etudes, Op.25, 1-3. From 78s, semi-private issue b 22800 12T 160 Topic m A1 £7.00 Folk Songs of Britain, 1 Child Ballads 1. Various artists (field recordings) e 22707 13029 AP DGG, Archiv, Ger., m A1 £40.00 Schneiderhan, Wolfgang, vn Bach: Partita 2, D minor, for solo violin. Sleeve: buff, gatefold 10" bb 22928 133 004 SLPE DGG, Ger., tulip, 10" s A1 £12.00 Bolechowska, Alina, s Chopin: Lieder. S. Nadgrizowski, pf a 22724 133 122 SLP DGG, Ger., red, tulip, s A1 £12.00 Markevitch, Igor, dir Mozart: Coronation Mass. -

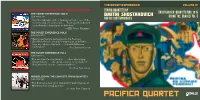

The Soviet Experience Volume Iv Also with the Pacifica Quartet on Cedille Records String Quartets by Shostakovich: Quartets Nos

THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOLUME IV ALSO WITH THE PACIFICA QUARTET ON CEDILLE RECORDS STRING QUARTETS BY SHOSTAKOVICH: QUARTETS NOS. 13-15 THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOL III DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH CDR 90000 138 SCHNITTKE: QUARTET No. 3 “This Shostakovich cycle is turning out to be one of the AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES most riveting of recent years. Pacifica’s Shostakovich cycle already is shaping up as definitive.” —BBC Music Magazine THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOLUME II STRING QUARTETS BY THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOL II DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES SHOSTAKOVICH: QUARTETS NOS. 1-- 4 CDR 90000 130 PROKOFIEV: QUARTET NO. 2 “Having reached the halfway point, the Pacifica’s Shostakovich cycle already is shaping up as definitive, even in a field stocked with . formidable Russian contenders.” PACIFICA QUARTET —The Classical Review SovietExpVol2_Mech.indd 1 12/9/11 10:41 AM THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOL I CDR 90000 127 “The excellent Pacifica Quartet . offers electrifying interpretations . The group conveys every shade of Shostakovich’s extreme emotional palette.” —The New York Times MENDELSSOHN: THE COMPLETE STRING QUARTETS CDR 90000 082 “This box sets a new gold standard for performances of Mendelssohn’s string quartets.” —St. Louis Post-Dispatch PACIFICA QUARTET SovietExpVol4_MECH.indd 1 10/2/2013 2:58:04 PM Producer & Engineer Judith Sherman THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOLUME IV PACIFICA QUARTET Assistant Engineer & Digital Editing Bill Maylone Shostakovich Quartet No. 14 and (most of) 15 Editing James Ginsburg STRING QUARTETS BY SHOSTAKOVICH: QUARTETS NOS. 13-15 Editing Assistance Jeanne Velonis DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH SCHNITTKE: QUARTET NO. 3 Recorded Shostakovich Quartets Nos. 13 and 14: December 16–18, 2012; Shostakovich Quartet No. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 28 No. 1, Spring 2012

y t e i c o S a l o i V n a c i r e m A e h t Features: 1 f IVC 39 Review r e o b Bernard Zaslav: m From Broadway u l to Babbitt N a Sergey Vasilenko's 8 n Viola Compositions 2 r e m u u l o V o J Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2012 Volume 28 Number 1 Contents p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President p. 7 News & Notes: Announcements ~ In Memoriam ~ IVC Host Letter Feature Articles p. 13 International Viola Congress XXXIX in Review: Andrew Filmer and John Roxburgh report from Germany p. 19 Bowing for Dollars: From Broadway to Babbitt: Bernard Zaslav highlights his career as Broadway musician, recording artist, and quartet violist p. 33 Unknown Sergey Vasilenko and His Viola Compositions: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives: Elena Artamonova uncovers works by Russian composer Sergey Vasilenko Departments p. 49 In the Studio: Yavet Boyadjiev chats with legendary Thai viola teacher Choochart Pitaksakorn p. 57 Student Life: Meet six young violists featured on NPR’s From the Top p. 65 With Viola in Hand: George Andrix reflects on his viola alta p. 69 Recording Reviews On the Cover: Karoline Leal Viola One Violist Karoline Leal uses her classical music background for inspiration in advertising, graphic design, and printmaking. Viola One is an alu - minum plate lithograph featuring her viola atop the viola part to Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony. To view more of her art, please visit: www.karolineart.daportfolio.com. -

Dissertation First Pages

Dissertation in Music Performance by Joachim C. Angster A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Dissertation Committee: Assistant Professor Caroline Coade, Co-Chair Professor David Halen, Co-Chair Professor Colleen Conway Associate Professor Max Dimoff Professor Daniel Herwitz Joachim C. Angster [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2563-2819 © Joachim C. Angster 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of my Doctoral Committee and to my teacher Professor Caroline Coade in particular, for making me a better musician. I also would like to give special thanks to my collaborators Arianna Dotto, Meridian Prall, Ji-Hyang Gwak, Taylor Flowers, and Nathaniel Pierce. Finally, I am grateful for the continuous support of my parents, and for the invaluable help of Anna Herklotz and Gabriele Dotto. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv FIRST DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 1 Program Notes 2 SECOND DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 18 Program Notes 19 THIRD DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 27 Program Notes 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 iii ABSTRACT This dissertation pertains to three viola recitals, which were respectively performed on 2 October 2019, 20 January 2020, and 9 March 2020. Each recital program embraced a specific theme involving little-performed works as well as staples from the viola repertoire, and covered a wide range of different musical styles. The first recital, performed with violinist Arianna Dotto, focused on violin and viola duo repertoire. Two pieces in the Classical and early Romantic styles by W. A. Mozart and L. -

Pragadigitals English 03-2018

catalogue Praga Digitals PRAGA DIGITALS CATALOGUE 03-2018 http://www.pragadigitals.com ISAAC ALBENIZ (1860-1909) CD1 : IBERIA, 12 “Impressions”, for piano (1905-1908) / Book I, dedicated to Madame Ernest Chausson (1906) /Book II, dedicated to Blanche Selva (1906) / Book III, dedicated to Marguerite Hasselmans (1907) / Book IV, dedicated to Madame Pierre Lalo (1908) PRD/DSD 350 075 CD2 : IBERIA Suite (transcriptions for orchestra by E.Fernández Arbós, 1909-1927) / CANTOS DE ESPAÑA, Op.232, for piano / ESPAÑA, “Souvenirs” for piano (1897) / MALLORCA, barcarola Op.202 (1891) / RECUERDOS DE VIAJE, Op.71 (1887) 3,149,028,025,927 SACD Alicia de LARROCHA, p (CD1) - Orchestre du Théâtre National de l’Opéra de Paris, Manuel ROSENTHAL - Jean-Joël BARBIER, p JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) PRD 250 103 SONATAS BWV 1020,1022,1027-1029, WRITTEN FOR HARPSICHORD & VIOLA 794,881,396,023 Zuzana Řů žicková (harpsichord), Josef Suk (viola) Mily BALAKIREV (1837-1910) Russian Symphonies (I) : PRD 250 363 SYMPHONY No.1 in C major (1866-99) SYMPHONY No.2 in D minor (1900-8) 3,149,028,102,024 Genuine Stereo The Philharmonia, London - Herbert von KARAJAN - Moscow Radio Symphony Gennadi ROZHDESTVENSKY BÉLA BARTÓK (1881-1945) PRD 250 135 VIOLIN SONATAS No 1 Sz.75 (1921) & No. 2 Sz.76 794,881,602,124 Peter Csaba (violin), Jean-François Heisser (piano) SONATAS FOR TWO PIANOS AND PERCUSSION Sz. 110. THE MIRACULOUS MANDARIN (written by Bartok for two pianos) . TWO PRD/DSD 250 184 PICTURES (written by Z.Kocsis for two pianos) 794,881,680,924 SACD Jean-François Heisser, Marie-Josèphe Jude (pianos), Florent Jodelet, Michel Cerutti (percussions) RHAPSODY Nos 1, 2 FOR VIOLIN and PIANO Sz.86 & Sz 89 (first release of the original Friss ), HUNGARIAN FOLK SONGS (26) (from PRD/DSD 250 190 FOR THE CHILDREN), RUMANIAN FOLK DANCES, SONATINA Sz 56 794,881,681,525 SACD Peter Csaba (violin), Peter Frankl (piano) STRING QUARTET No 1 SZ 40 PRD/DSD 250 235 STRING QUARTET No 2 SZ 67 794,881,822,423 SACD Parkanyi Quartet Page 1 de 58 catalogue Praga Digitals STRING QUARTET No. -

Approaches to the Performance of Musical and Extra-Musical References in Shostakovich’S Viola Sonata

Approaches to the Performance of Musical and Extra-musical References in Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata By John David Roxburgh Exegesis Submitted to Massey University and Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Musical Arts In Performance New Zealand School of Music 2013 i Abstract Approaches to the Performance of Musical and Extra-musical References in Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata by John David Roxburgh Supervisor: Professor Donald Maurice Secondary Supervisor: Dr David Cosper This paper is an examination of Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata, op. 147, for developing a stylistically informed performance practice. It is divided into three parts: The first is an investigation of symbolism present within the work itself; the second a comparative analysis of recordings; and the third a discussion of how the author uses these approaches to make performance decisions. The first aspect looks to the score itself to identify quotations of and allusions to other works, and considers the reasoning for this. The second analyses string choice and tempo of recordings to consider how these might reflect symbolic considerations. The third part discusses specific performance decisions, and the reasons on which they are based. ii Table of Contents Title Page i Abstract ii Table of Contents iii List of Recording Examples iv Introduction 1 Part I: Investigation of Musical and Extra-Musical References 4 Part II: Comparative Analysis of Recordings 23 Part III: Discussion of Performance Decisions 36 Conclusion 39 Bibliography 42 Appendix I: String Choice Analysis 45 Appendix II: Tempo Analysis 91 iii List of Recording Examples (on audio CD attached) Track No. -

Contemporary Special Classics Jazz

NEOS CONTEMPORARY SPECIAL CLASSICS JAZZ www.neos-music.com La Fundación BBVA es expresión de la responsabilidad corporativa de BBVA, un grupo global de servicios financieros comprometido con la mejora de las sociedades en las que desarrolla su actividad. La Fundación BBVA centra su actividad en el apoyo a la generación de conocimiento, la investigación científica y el fomento de la cultura, así como en su difusión a la sociedad. Entre sus áreas de actividad preferente figuran las ciencias básicas, la biomedicina, la ecología y la biología de la conservación, las ciencias sociales, la creación literaria y la música. La Fundación BBVA ha establecido los Premios Internacionales Fronteras del Conocimiento y la Cultura como reconocimiento a contribuciones especialmente significativas en la investigación científica de vanguardia y en la creación en el ámbito de la música y las artes. La Fundación BBVA colaborará durante los próximos años con el prestigioso sello discográfico NEOS Music en lagrabación y difusión de una amplia selección de la música contemporánea más creativa, así como en la realización de versiones especiales de obras clásicas. Con esta iniciativa se pretende facilitar el acceso por parte de un público amplio a una dimensión de la cultura de nuestro tiempo particularmente innovadora. *** The BBVA Foundation expresses the corporate responsibility of BBVA, a global financial services group committed to working for the improvement of the societies in which it does business. The Foundation supports knowledge generation, scientific research, and the promotion of culture, ensuring that the results of its work are relayed to society at large. Among its preferred areas of activity are the basic sciences, biomedicine, ecology and conservation biology, the social sciences and literary and musical creation. -

Swiss Chamber Soloists

www.fbbva.es www.neos‐music.com COLLECTION BBVA FOUNDATION ‐ NEOS Mieczysław Weinberg Complete sonatas for Viola Solo Fyodor Druzhinin Sonata for Viola Solo MIECZYSŁAW WEINBERG REDISCOVERY OF A FORGOTTON GENIUS The death in Moscow of the composer Mieczysław Weinberg in February 1996 was hardly noticed in Russia or abroad. This was perhaps not surprising, considering Weinberg’s shadowy existence in the Soviet Union. His status in musical life was in many ways paradoxical: in the capital he was held in great esteem by composer colleagues and by renowned interpreters too, but in wider musical circles and amongst a music‐loving public he remained largely unknown. His music was performed only infrequently and over 70% of his works were not published during his lifetime. Weinberg composed music to some of the most famous soviet films, but even this did not do anything for his popularity. He was a real outsider, although he was a member of the Soviet Association of Composers and had at least garnered several official awards. For over 50 years Weinberg lived and worked in Moscow, but remained somehow in a parallel world: he did not take part in the usual business of music, the struggle to secure commissions and privileges, trips abroad and publications. He was Jewish, did not join the Communist Party and spoke Russian with a strong foreign accent. Weinberg was an unusual modest and reserved person, and this explains in some measure why a composer whose music is presently enjoying something of a renaissance around the world was so ignored whilst he was alive. -

Krysa Discography

OLEH KRYSA DISCOGRAPHY BIS label Ernest Bloch. Violin Concerto Oleh Krysa, Violin Malmo Symphony Orchestra, Sakari Oramo, Conductor Sofia Gubaidulina. “Offertorium”. Concerto for Violin and Orchestra “Rejoce!” Sonata for Violin and Cello Oleh Krysa, Violin, Torleif Thedeen, Cello Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, James de Preist, Conductor Alfred Schnittke . Violin Concertos Nos. 3 & 4 Oleh Krysa, Violin Malmo Symphony Orchestra, Eri Klas, Conductor Alfred Schnittke. Concerto Grosso No. 2 for Violin, Cello and Orchestra Oleh Krysa, Violin, Torleif Thedeen, Cello Malmo Symphony Orchestra, Lev Markiz, Conductor Alfred Schnittke. Chamber Music Prelude in memoriam Dmitri Shostakovih for Two Violins Moz-Art for Two Violins Stille Musik for Violin and Cello Madrigal in memoriam Oleg Kagan for solo Violin Madrigal in memoriam Oleg Kagan for solo Cello Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano Oleh Krysa, Violin, Alexandr Fisher, Violin, Torleif Thedeen, Cello, Tatiana Tchekina, Piano Erwin Schulhoff. Sonata for solo Violin Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2 Duo for Violin and Cello Oleh Krysa, Violin, Tatiana Tchekina, Piano, Torleif Thedeen, Cello Maurice Ravel. Sonata for Violin and Cello Bohuslav Martinu. Duo No. 1 for Violin and Cello Arthur Honegger. Sonatina for Violin and Cello Erwin Schulhoff. Duo for Violin and Cello Oleh Krysa, Violin, Torleif Thedeen, Cello -2- TNC RECORDINGS label Ludwig van Beethoven. Violin Concerto in D Major, op. 61 Oleh Krysa, Violin Kiev Camerata, Virko Baley, Conductor Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. Violin Concerto in E minor, op. 64 Johannes Brahms. Violin Concerto in D Major, op. 77 Giovanni Battista Viotti. Violin Concerto No. 22 in A minor Max Bruch. Scottish Fantasy, op. -

An Examination on D. Shostakovich's Viola Sonata Op.147 from A

Konservatoryum - Conservatorium Cilt/Volume: 7, Sayı/Issue: 2, 2020 ISSN: 2146-264X E-ISSN: 2618-5695 RESEARCH ARTICLE / ARAŞTIRMA MAKALESİ An Examination on D. Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata Op.147 from a Technical Perspective D. Shostakovich Viyola Sonati Op.147 Üzerine Teknik Açidan Bir İnceleme Füsun Naz ALTINEL1 ABSTRACT The purpose of this article is to provide a resource to those who wish to gain a deeper understanding on the technical aspects of Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata Op. 147 based on F. Druzhinin’s edited viola part. This study consists of two methods; books are used as research material to provide an overview on composers life DOI: 10.26650/CONS2020-0011 and music, extracts from F. Druzhinin’s viola part and recordings are examined to provide technical suggestions to performers. Preparing this article, books and F. Druzhinin’s viola part are obtained from the library of Royal Northern College of Music. For the recording of Fyodor Druzhinin, youtube is used as online resource. The headlines inside the study are as follows; an overview of Shostakovich’s life and viola sonata, other composers and artists that have influenced Shostakovich’s music (Ludwig Van Beethoven and Nicolai Gogol) and performance suggestions given based on F. Druzhinin’s viola part and recording. For the music examples in this article Moscow: Publishers Musika, 1984, Collected Works in forty-two volumes: (Vol.38, viola part edited by F. Druzhinin) is used. Keywords: Shostakovich, Viola, Sonata 1Dr., Karşıyaka Belediyesi Oda Orkestrası- Viyola Sanatçısı, İzmir, Türkiye ÖZ Bu makalenin amacı Shostakovich’in Op. 147 viyola Sonatını çalışmak isteyen ORCID: F.N.A. -

Wydział Instrumentalny – Krzysztof Komendarek-Tymendorf „Zagadni

Akademia Muzyczna im. Stanisława Moniuszki w Gdańsku – Wydział Instrumentalny – Krzysztof Komendarek-Tymendorf „Zagadnienia wykonawcze i interpretacyjne Sonaty na altówkę solo (1959) Fiodora Drużynina oraz Sonaty na altówkę solo nr 3 op. 135 (1982) Mieczysława Wajnberga” Promotor: prof. zw. dr hab. Irena Albrecht Twórczość Fiodora Drużynina (urodzonego 6 marca 1932 roku w Moskwie) altowiolisty, rosyjskiego kompozytora, jest absolutnie nie odkryta oraz nie popularyzowana zarówno w Polsce, jak i na całym świecie. Ów artysta to jeden z najbardziej prominentnych altowiolistów XX wieku w ZSRR. Był najsłynniejszym radzieckim altowiolistą, kompozytorem, aranżerem oraz pedagogiem. Skomponował wiele dzieł na altówkę, w tym między innymi opisywaną przez twórcę tegoż wywodu Sonatę na altówkę solo (1959). Opracowywał również transkrypcje wielu dzieł na altówkę. Dorobek artystyczny Mieczysława Wajnberga (urodzonego 8 grudnia 1919 roku w Warszawie), jego wkład do światowej kultury jest także bezsprzecznie nieoceniony. Wiele źródeł donosi, iż jest on rosyjskim kompozytorem, mimo tego, że sam uważał się zawsze za Polaka. Zapewne gdyby nie wojna i to, że musiał – w trakcie pobierania nauki w Konserwatorium Warszawskim – uciekać z rodziną w roku 1939, to nie wyjechałby do ZSRR. Artysta został uchodźcą z okupowanej Polski. Czasy stalinowskie w dużym stopniu ograniczały jego autonomię w komponowaniu. Podobnie jak Dymitr Szostakowicz, znalazł sposób na przekazanie rzeczywistości poprzez muzykę. Sonata na altówkę solo nr 3 op. 135 (1982) Mieczysława Wajnberga jest częścią większego cyklu: czterech sonat na altówkę solo. W tymże zbiorze dzieł, napisanych między rokiem 1971 a 1983, możemy odnaleźć w jego muzyce: nostalgię, smutek, pesymizm, melancholię, mizerność, ironię i żydowskie motywy melodyczne. Wajnberg w pełni zdawał sobie sprawę z faktu, iż muzyczne pożegnanie Szostakowicza w jego ostatnim dziele, tj.