Flexural Cracking in Concrete Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Concrete Repair Second Edition

ON r in the West August 2015 Guide to Concrete Repair Second Edition Prepared by: Kurt F. von Fay, Civil Engineer Concrete, Geotechnical, and Structural Laboratory U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center August 2015 Mission Statements The U.S. Department of the Interior protects America’s natural resources and heritage, honors our cultures and tribal communities, and supplies the energy to power our future. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Acknowledgments Acknowledgment is due the original author of this guide, W. Glenn Smoak, for all his efforts to prepare the first edition. For this edition, many people were involved in conducting research and field work, which provided valuable information for this update, and their contributions and hard work are greatly appreciated. They include Kurt D. Mitchell, Richard Pepin, Gregg Day, Jim Bowen, Dr. Alexander Vaysburd, Dr. Benoit Bissonnette, Maxim Morency, Brandon Poos, Westin Joy, David (Warren) Starbuck, Dr. Matthew Klein, and John (Bret) Robertson. Dr. William F. Kepler obtained much of the funding to prepare this updated guide. Nancy Arthur worked extensively on reviewing and editing the guide specifications sections and was a great help making sure they said what I meant to say. Teri Manross deserves recognition for the numerous hours she put into reviewing, editing and formatting this Guide. The assistance of these and numerous others is gratefully acknowledged. Contents PART I: RECLAMATION'S METHODOLOGY FOR CONCRETE MAINTENANCE AND REPAIR Page A. -

Reinforcing Steel Cover When Reinforcing Steel Is Too Close to the Surface, It Begins Rusting and Expanding, Causing the Surrounding Concrete to Break Away

BRANZ FACTS MID-RISE BUILDINGS #4 Exposed issues – reinforcing steel cover When reinforcing steel is too close to the surface, it begins rusting and expanding, causing the surrounding concrete to break away. STEEL REINFORCING BARS are used in concrete and concrete masonry to provide resistance to tensile loads and for concrete slabs and panels to help limit the risk of shrinkage cracking as the material cures. The steel relies on being sufficiently deep (called cover) within the concrete to protect it from moisture and corrosion. Where it is too close to the surface or the concrete is poor quality, it will begin rusting. As steel rusts, it expands, and this can result in concrete spalling – where pieces of concrete are broken away by the expanding steel. As the concrete breaks away or cracks, more moisture can get in and the deterioration will accelerate. The corrosion will also reduce the tensile strength of the steel as the steel deteriorates. How much cover? How much cover depends on: NZS 4229:2013 Concrete masonry buildings Tables 1 and 2 outline the requirements ● what the steel is embedded in – concrete not requiring specific engineering design: from NZS 3101.1&2:2006 Concrete structures or the grouted cells of concrete masonry ● For concrete masonry: standard. ● concrete or grout strength • 45 mm in exposure zone B For concrete masonry structures built to ● what the surface of the concrete is • 50 mm in exposure zone C NZS 4229:2013, the cover requirements from exposed to – soil or air • 60 mm in exposure zone D. the external face of uncoated masonry are: ● the corrosion or environmental zone ● For concrete: ● for exposure zone B – 45 mm with 17.5 ● the type of steel used – mild steel, • 75 mm for concrete placed directly on MPa grout galvanised, stainless steel or against the ground (can be reduced ● for exposure zone C – 50 mm with 20 ● intended life of the structure to 50 mm where there is a DPM MPa grout ● cement type. -

Reinforcing Footings Cover Do You Know the Minimum Bending Diameter for Reinforcing Steel and Its Cover

MINIMUM DIMENSIONS AND COVER FOR CONCRETE FOOTINGS WITH REINFORCING STEEL BUILD RIGHT Reinforcing footings cover Do you know the minimum bending diameter for reinforcing steel and its cover BY TREVOR PRINGLE, requirements in concrete footings? This determines the minimum width you ANZIA, BRANZ PRINCIPAL need to make your concrete footings. WRITER SOME DIMENSIONS GIVEN in NZS 3604:2011 Bending diameters 5 × bar diameter ● the bar diameter Timber-framed buildings for reinforced concrete For foundation walls to concrete slabs, the ● the bar bend diameter. foundation footings may be insufficient. This horizontal bars are typically D12 and the is due to the bending diameters and minimum vertical starter bars are R10. Two D12s stacked concrete cover required for steel reinforcing in Minimum bending diameters for reinforcing For a foundation non-cantilevered wall using concrete footings. steel are given in Tables 8.1 and 8.2 of NZS two D12s horizontally with R10s vertically, the 3101.1&2:2006 Concrete structures standard. minimum width (see Figure 1) will be: Footing widths in NZS 3604:2011 According to Table 8.1, the bending diameter ● cover on each side: 2 × 75 mm = 150 mm NZS 3604:2011 section 7.5 sets out require- for 6–20 mm diameter deformed and plain ● vertical bar diameter: 2 × 10 mm = 20 mm ments for reinforced concrete foundation walls steel reinforcing bars must be at least five ● minimum bend diameter: 5 × 10 mm = and footings for concrete slabs on ground. times the bar diameter. Therefore, the 50 mm. Figures 7.13(B), 7.14(B and C) and 7.16 (B and C) reinforcing bar minimum bending diameter This gives a minimum foundation width of give minimum footing width dimensions. -

Alkali-Aggregate Reactions 162 163

161 Session A7: ALKALI-AGGREGATE REACTIONS 162 163 Alkali release from typical Danish aggregates to potential ASR reactive concrete Hans Chr. Brolin Bent Grelk Thomsen M.Sc, Chief Consultant M.Sc Grelk Consult DTU Civil Engineering [email protected] Brovej, Building 118 DK - 2800 Kgs. Lyngby [email protected] Ricardo Antonio Kurt Kielsgaard Hansen Barbosa Associated professor, Ph.D. Ph.D. DTU Civil Engineering DTU Civil Engineering Brovej, Building 118 Brovej, Building 118 DK - 2800 Kgs. Lyngby DK - 2800 Kgs. Lyngby [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Alkali-silica reaction (ASR) in concrete is a well-known deterioration mechanism affecting the long term durability of Danish concrete structures. Deleterious ASR cracking can be significantly reduced or prevented by limiting the total alkali content of concrete under a certain 3 threshold limit, which in Denmark is recommended to 3 kg/m Na2Oeq.. However, this threshold limit does not account for the possible internal contribution of alkali to the concrete pore solution by release from aggregates or external contributions from varies sources. This study 3 indicates that certain Danish aggregates are capable of releasing more than 0.46 kg/m Na2Oeq. at 13 weeks of exposure in laboratory test which may increase the risk for deleterious cracking due to an increase in alkali content in the concrete. Key words: Alkali-silica reaction, aggregate, alkali content, durability. 1. INTRODUCTION ASR is a complex physical and chemical reaction between water, alkali in the concrete pore solution and reactive silica minerals in aggregates [1]. The reaction demands an alkaline environment which is found inside the concrete where a natural presence of free calcium hydroxide is found. -

SECTION 03300 CAST-IN-PLACE CONCRETE PART 1 GENERAL 1.01 SUMMARY A. This Section Covers Formwork, Reinforcing Steel, and Cast-In

SECTION 03300 CAST-IN-PLACE CONCRETE PART 1 GENERAL 1.01 SUMMARY A. This section covers formwork, reinforcing steel, and cast-in-place Concrete work. B. Related Work Specified Elsewhere 1. Manholes: Section 02605 2. Storm Sewer Collection System: Section 02722 C. Measurement and Payment Procedures 1. For public funded capital improvement projects, measurement and payment procedures will be determined on a project by project basis. 2. For privately funded development projects, Owner will determine measurement and payment requirements. 1.02 REFERENCES A. American Concrete Institute (ACI) International 1. ACI 305 – Hot Weather Concreting 2. ACI 306 – Cold Weather Concreting 3. ACI 309 – Standard Practice for Consolidation of Concrete 4. ACI 318 – Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary B. American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) 1. ASTM A82 – Standard Specification for Steel Wire, Plain, for Concrete Reinforcement 2. ASTM A185 – Specification for Steel Welded Wire Fabric, Plain, for Concrete Reinforcement 3. ASTM A615 – Deformed and Plain Billet-Steel Bars for Concrete Reinforcement 4. ASTM A996 – Specification for Rail-Steel and Axle-Steel Deformed Bars for Concrete Reinforcement 5. ASTM C31 – Making and Curing Concrete Test Specimens in the Field 6. ASTM C33 – Concrete Aggregates 7. ASTM C39 - Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens 8. ASTM C94 – Ready-Mixed Concrete 9. ASTM C143 – Slump of Hydraulic Cement Concrete 10. ASTM C150 – Portland Cement 11. ASTM C171 – Sheet Materials for Curing Concrete 12. ASTM C231 – Air Content of Freshly Mixed Concrete by the Pressure Method. 13. ASTM C260 – Air-Entraining Admixtures for Concrete 14. ASTM C309 – Liquid Membrane-Forming Compounds for Curing Concrete 15. -

The Symposium Took Place 13Th to 15Th August 2014

PUBLICATION NO. 50 2/2014 NORDIC CONCRETE RESEARCH EDITED BY THE NORDIC CONCRETE FEDERATION CONCRETE ASSOCIATIONS OF: DENMARK FINLAND ICELAND NORWAY SWEDEN PUBLISHER: NORSK BETONGFORENING POSTBOKS 2312, SOLLI N - 0201 OSLO NORWAY PROCEEDING XXII NORDIC CONCRETE RESEARCH SYMPOSIA REYKJAVIK, ICELAND 2014 iii PUBLICATION NO. 50 2/2014 CONTENTS OPENING SESSION 1 Tor Arne Martius-Hammer 3 COIN - Main Achievements 1 DURABILITY, MAINTENANCE, RENOVATION & FROST ACTION - 7 PER FIDJEST0L MEMORIAL SESSION R. Doug Hooton 9 Advantages of Silica Fume-Slag Ternary Binders for Production of Dura¬ ble Concrete Olafur H. Wallevik, Indri6i Nielsson & Bjorn Hjartarson 13 Self-compacting concrete without chemical admixture for Per Fidjestol Martin Kaasgaard, Claus Pade, UlfJonsson & Christian Munch-Petersen 17 Comparison of Durability Parameters of Self-Compacting Concrete and Conventional Slump Concrete Designed for Marine Environment Marianne Tange Hasholt 21 The Interplay Between Inner and Outer Frost Damage and its Implication for Accelerated Freeze-Thaw Testing Jonny Nilimaa, Jens Haggstrom, Niklas Bagge, Thomas Blanksvard, Gabriel 25 Sas, Ulf Ohlsson, Lars Bernspang, Bjorn Taljsten, Lennart Elfgren, Anders Carolin, Hakan Thun & Bjorn Paulsson Maintenance and Renewal of Concrete Rail Bridges - Results from EC Project MAINLINE 2 STRUCTURAL BEHAVIOUR AND DESIGN 29 Tarek Edrees Saaed, George Nikolakopoulos & Jan-Erik Jonasson 31 Semi-Active Structural Control Strategies Linn Grepstad Nes & Jan Arve 0verli 35 Structural Behaviour of Beams with Fibre Reinforced LWAC and Normal Density Concrete Mario Plos, Costin Pacoste & Morgan Johansson 39 Recommendations for Finite Element Analysis for Design of RC Slabs Havard Nedrelid & Terje Kanstad 43 Tests and Design of Fibre-Reinforced RC Beams with Dapped Ends Morten Engen, Max A. -

Architectural Precast Concrete Wall Panels: Their Technological Evolution, Significance, and Preservation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2016 Architectural Precast Concrete Wall Panels: Their Technological Evolution, Significance, and Preservation Grace Meloy University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Meloy, Grace, "Architectural Precast Concrete Wall Panels: Their Technological Evolution, Significance, and Preservation" (2016). Theses (Historic Preservation). 608. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/608 Suggested Citation: Meloy, Grace (2016). Architectural Precast Concrete Wall Panels: Their Technological Evolution, Significance, and Preservation. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/608 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Architectural Precast Concrete Wall Panels: Their Technological Evolution, Significance, and Preservation Abstract Architectural precast concrete wall panels played an important role in mid-twentieth century architecture by providing a concrete technology that could be applied to the curtain wall system of construction utilized in this time period. Moreover, the precasting process, which enabled the controlled production of expressive facing concrete mixes and surface treatments and finishes, made this a concrete technology that could contribute to the architectural -

ACI 302.1R-15: Guide to Concrete Floor

The attached excerpted resource materials have been made available for use within ACI University. To obtain a full version of this document, please visit the ACI Store. For additional education products, please visit ACI University. ACI 302.1R-15 Guide to Concrete Floor and Slab Construction Reported by Committee 302 Joseph F. Neuber Jr., Chair Russell E. Neudeck, Secretary Patrick J. Harrison, Vice Chair Dennis C. Ahal Jerry A. Holland Nigel K. Parkes Carl Bimel* Bryan M. Birdwell Philip S. Kopf William S. Phelan Michael A. Clark Peter A. Craig Steve R. Lloyd, Sr. Tim H. Robinson William C. Panarese Allen Face Kevin A. MacDonald John W. Rohrer Brian J. Pashina C. Rick Felder Arthur W. McKinney Paul A. Rouis, III Boyd C. Ringo* Edward B. Finkel Donald M. McPhee Domenick Thomas Ruttura Barry E. Foreman Scott C. Metzger Bruce A. Suprenant *Deceased Greg K. Fricks Jeffrey S. Miller Scott M. Tarr Terry J. Fricks Scott L. Niemitalo Consulting Members The quality of a concrete floor or slab is highly dependent on on every project, and that such an occurrence does not necessarily achieving a hard and durable surface that is flat, relatively free reflect adversely on either the adequacy of the floor’s design or the of cracks, and at the proper grade and elevation. Properties of the quality of its construction (Ytterberg 1987). surface are determined by the mixture proportions and the quality This guide describes how to produce high-quality concrete slabs- of the concreting and jointing operations. The timing of concreting on-ground and suspended floors for various classes of service. -

ASR) and Alkali-Carbonate Reaction (ACR)

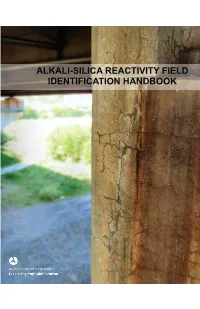

ALKALI-SILICA REACTIVITY FIELD IDENTIFICATION HANDBOOK Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-HIF-12-022 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Alkali-Silica Reactivity Field Identification Handbook December 2011 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Thomas, M.D.A., Fournier, B., Folliard, K.J., Resendez, Y.A. 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. The Transtec Group, Inc. 6111 Balcones Drive Austin, TX 78731 11. Contract or Grant No. DTFH61-06-D-00035 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Office of Pavement Technology Final Report December 2011 Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue, DE Washington, DC 20590 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Contracting Officer’s Technical Representative (COTR): Gina Ahlstrom, HIPT-20 16. Abstract Two types of alkali-aggregate reaction (AAR) are currently recognized depending on the nature of the reactive mineral; these are alkali-silica reaction (ASR) and alkali-carbonate reaction (ACR). Both types of reaction can result in expansion and cracking of concrete elements, lead ing to a reduction in the service life of concrete structures. This handbook serves as an illustrated guide to assist users in detecting and distin guishing ASR in the field from other types of damages. 17. Key Words 18. Distribution Statement Alkali-silica reactivity, alkali-aggregate reaction, reactive No restrictions. This document is available to the public through the Na aggregates, concrete durability, field identification, concrete tional Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161. -

Enhanced Mechanical and Durability Performances of Low Cement Concrete with Natural Pozzolan Addition

Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology Vol. 19, 519-535, May 2021 / Copyright © 2021 Japan Concrete Institute 519 Scientific paper Enhanced Mechanical and Durability Performances of Low Cement Concrete with Natural Pozzolan Addition Keila Robalo1, Hugo Costa2*, Ricardo do Carmo3 and Eduardo Júlio4 Received 6 November 2020, accepted 3 May 2021 doi:10.3151/jact.19.519 Abstract The decarbonization of concrete structures sector is a priority due to the world climate. Since Portland cement is re- sponsible for approximately 7% of the anthropogenic emissions worldwide, it is decisive to partially replace it by prod- ucts with lower environmental impact. Fly ash has become highly demanded, due to its proven advantages, however, has announced end by the developed countries. The purpose of this research is to develop and characterize low cement concrete (LCC) with natural and ecological pozzolan additions as an alternative to fly ash. The main objectives are: define several structural concrete mixtures with low cement dosage, ranging from 125 to 175 kg/m3; characterize the workability and the mechanical properties, beyond the durability performance of those concretes; study the influence of pozzolans additions on LCC performance, as an alternative to fly ash; assess the service life of structures produced with the developed LCC. It is possible to produce LCC with natural pozzolan additions, instead of fly ash, with improved mechanical properties and enhanced durability performances. Results also show that the structural LCC produced with pozzolan from Cape Verde provide a great protection against steel corrosion, achieving values 50% higher than concrete with fly ash, and even higher margins when compared with the minimum concrete covers recommended by standards, which highlights the benefits of its use from the sustainability point of view. -

Sustainable Benefits of Concrete Structures

Copyright: Foreword European Concrete Platform ASBL, February 2009 Sustainability lies at the heart of construction and design. A sustainable approach of construction brings lasting environmental, All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be re- produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in social and economic benefits to a construction project. From that any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, perspective, concrete achieves high valuable properties as a con- photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior struction material limiting the impacts of a building or infrastructure written permission of the European Concrete Platform on its surroundings. ASBL. Published by the European Concrete Platform ASBL Acknowledgements Editor: Jean-Pierre Jacobs 1050 Brussels, Belgium This was originally written and published in 2007 by the Environ- Layout & graphic design: Geert Joostens bvba JO-OP mental Working Group of Betonikeskus ry, in Finland, under the title Printing by the European Concrete Platform ASBL Environmental properties of concrete structures. All information in this document is deemed to be ac- We thank Laetitia Dévant for her work Europeanizing the book, the curate by the European Concrete Platform ASBL at the English Centre for the translation, the British Precast (particularly time of going into press. It is given in good faith. Martin Clarke and Chrissie Walton), Gillian Bond and Brian O’Murchu Information on European Concrete Platform documents for their revisions, and Geert Joostens for his inspired and insightful does not create any liability for its Members. While the goal is to keep this information timely and accurate, the design. European Concrete Platform ASBL cannot guarantee We pay all due respect to all the people from the European Con- either. -

Conserving Concrete Heritage

Literature Review Conserving Concrete Heritage An Annotated Bibliography Edited by Alice Custance-Baker Gina Crevello Susan Macdonald Kyle Normandin Conserving Concrete Heritage: An Annotated Bibliography Alice Custance-Baker, Gina Crevello, Susan Macdonald, and Kyle Normandin THE GEttY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES Conserving Concrete Heritage: An Annotated Bibliography © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust The Getty Conservation Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 700 Los Angeles, CA 90049-1684 United States Telephone 310 440-7325 Fax 310 440-7702 E-mail [email protected] www.getty.edu/conservation ISBN: 978-1-937433-27-7 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-937433-28-4 (online resource) The Getty Conservation Institute works to advance conservation practice in the visual arts, broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. It serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, model field projects, and the dissemination of the results of both its own work and the work of others in the field. And in all its endeavors, the GCI focuses on the creation and dissemination of knowledge that will benefit the professionals and organizations responsible for the conservation of the world’s cultural heritage. Front cover: Fireplace Detail. Hollyhock House, Los Angeles, California (Frank Lloyd Wright, 1919–21). Photography by Joshua White/JWPictures.com. Courtesy of Hollyhock House. Conserving Concrete Heritage: An Annotated Bibliography Contents Introduction 5 CHAPTER ONE History and Development