ᖃᓪᓗᓈᖅᑕᐃᑦ ᓯᑯᓯᓛᕐᒥᑦ Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios Exhibition Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wearing Our Identity – the First People's Collection

Wearing our Identity – The First People’s Collection Texts of the exhibition Table of content Introduction 2. Fashioning identity 2. 1 – Wearing who I am 3. 1.1 – Wearing where I come from 3. 1.2 – Wearing life’s passages 3. 1.3 – Wearing my family 6. 1.4 – Wearing my rank 7. 2 – Wearing our culture 10. 2.1 – Wearing our traditions 10. 2.2 – Wearing our legends 15. 2.3 – Wearing our present 16. 3 – Wearing our history 17. 3.1 – Wearing our honour 18. 3.2 – Wearing our struggles 20. 3.3 – Wearing our resilience 21. 4 – Wearing our beliefs 23. 4.1 – Wearing our universe 23. 4.2 – Wearing animal power 24. 4.3 – Wearing spiritual respect 25. 2 Wearing our Identity – The First People’s Collection © McCord Museum, 2013 0 – Introduction Wearing Our Identity The First Peoples Collection Questions of identity lie at the heart of many debates in today’s rapidly changing world. Languages and traditions are threatened with extinction. When this happens, unique knowledge, beliefs and histories are wiped out. First Peoples understand well the challenges and tensions that can erode a sense of self and belonging. Yet, they have shown remarkable resilience in both preserving ancient identities and forging new ones. Whether building on the rich textures of the past or fearlessly transforming contemporary fashion, First Nations, Inuit and Métis use clothing to communicate the strength and meaning of their lives. An exploration of First Peoples dress is a compelling and emotional experience – one that must follow interwoven threads of community and spirituality, resistance and accommodation, history and innovation. -

Of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Nunavut, Canada

english cover 11/14/01 1:13 PM Page 1 FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove Principal Researchers: Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove PO Box 1379 Principal Researchers: Iqaluit, Nunavut Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and X0A 0H0 Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike Cover photo: Glenn Williams/Ursus Illustration on cover, inside of cover, title page, dedication page, and used as a report motif: “Arvanniaqtut (Whale Hunters)”, sc 1986, Simeonie Kopapik, Cape Dorset Print Collection. ©Nunavut Wildlife Management Board March, 2000 Table of Contents I LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . .i II DEDICATION . .ii III ABSTRACT . .iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY . .1 1.2 TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENCE . .1 2 METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 PLANNING AND DESIGN . .3 2.2 THE STUDY AREA . .4 2.3 INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES AND THE QUESTIONNAIRE . .4 2.4 METHODS OF DATA ANALYSIS . -

Sophie Frank

LINEAGES AND LAND BASES FINAL DIDACTICS 750 Hornby Street Vancouver BC V6Z 2H7 Canada Tel 604 662 4700 Fax 604 682 1787 www.vanartgallery.bc.ca lineages and land bases The artworks gathered for this exhibition address differing understandings lineages and land bases presents works from the Vancouver Art Gallery’s of the self and personhood in relation to nature, a concept that is culturally, permanent collection by artists who have challenged the nature-culture historically and linguistically informed. divide, seeking new ways to conceptualize and represent their relation to the world around them while grappling with the troubled inheritance of settler Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim (the Squamish language) has no word for nature, colonialism. At the centre of the exhibition is a case study that assesses the although it has many words that relate to the land and water. Within this intersections between the basketry of Sewiṉchelwet (Sophie Frank) (1872– worldview, people are intimately bound to non-human entities, such as plants, 1939), a woman from the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation), and rocks, animals or places, locating subjectivity well beyond humans. In contrast, the late landscape paintings of Emily Carr (1871–1945). The two women were the modern Euro-Canadian distinction between nature and culture provided close contemporaries and friends for 33 years, a relationship also shaped by the foundation, in the early 20th century, for the development of a national the profound inequalities of their time. The comparison of these two distinct, art and identity in Canada. Paintings of vast empty landscapes premised yet interconnected, perspectives both prefigures and extends the critique of an idea of wilderness that effectively erased Indigenous presence from the the separation of nature and culture seen elsewhere in the exhibition, urging us representation of nature at the same time that these communities were being to think anew about the meaning of self and its ties to the non-human world. -

Kivia Covid 19 Response Initiative Phase 2

KivIA Covid 19 Response Initiative Phase 2 December 8, 2020 By KIA Announcements / Inuit Programs & Services RANKIN INLET, NU – December 7, 2020 – The Kivalliq Inuit Association (KivIA) is pleased to announce the launch of the second phase of its COVID-19 initiatives for its members. Initiatives that included support for its Elders, traditional activities, and support to all its members within our communities had ended. The additional funds for KivIA’s second phase COVID-19 response plan come from additional funding from the Indigenous Community Support Fund (ICSF). The KivIA had carefully considered various options to roll out this additional funding from the federal government. The discussion led to a consensus on a plan that would… Eliminate the need to have the program become application based Allow the general public, KIA staff and Inuit to not come in contact with each other in order to carry out this program, therefore following the Public Health Measures currently in effect. Allow the Inuit in the Kivalliq communities to quickly receive the relief funds without any delay due to administrative time. Benefit local Inuit owned companies with their services Maximize the funding effectiveness with the addition of added funds from the vendor and ability for its members to add on to their dividends. Prevent any tax implications for the Inuit from the federal government in receiving this relief funding. With the above factors put into consideration, it was suggested by the Covid-19 Planning Committee that the ICS Funding would be rolled out with a partnership with the Arctic Cooperatives Limited to provide $1500 gift cards to every Inuit household in the Kivalliq Region. -

Press Release Neas Awarded New Exclusive Carrier Contracts for Nunavut

PRESS RELEASE NEAS AWARDED NEW EXCLUSIVE CARRIER CONTRACTS FOR NUNAVUT - New for 2019: NEAS is now the Government of Nunavut’s (GN) dedicated carrier for Iqaluit, Cape Dorset, Kimmirut, Pangnirtung, Arctic Bay, Qikiqtarjuaq, Clyde River, Grise Fiord, Pond Inlet, Resolute Bay, Baker Lake, Chesterfield Inlet, Rankin Inlet, Whale Cove, Arviat, Coral Harbour, Kugaaruk, Sanikiluaq, and the Churchill, MB, to Kivalliq service. - Another arctic sealift first for 2019: Kugaaruk customers can now reserve direct with NEAS for the Valleyfield to Kugaaruk service, with no need to reserve through the GN; - “The team at NEAS is thankful for the Government of Nunavut’s vote of confidence in our reliable arctic sealift operations,” said Suzanne Paquin, President and CEO, NEAS Group. “We look forward to delivering our customer service excellence and a better overall customer sealift experience for all peoples, communities, government departments and agencies, stores, construction projects, mines, defence contractors and businesses across Canada’s Eastern and Western Arctic.” IQALUIT, NU, April 25, 2019 – The 2019 Arctic sealift season is underway, and the team of dedicated professionals at the NEAS Group is ready to help you enjoy the most reliable sealift services available across Canada’s Eastern and Western Arctic. New this season, NEAS is pleased to have been awarded the exclusive carrier contracts for the Government of Nunavut including Iqaluit and now Cape Dorset, Kimmirut, Pangnirtung, Arctic Bay, Qikiqtarjuaq, Clyde River, Grise Fiord, Pond Inlet, Resolute Bay, Baker Lake, Chesterfield Inlet, Rankin Inlet, Whale Cove, Arviat, Coral Harbour, Kugaaruk, Sanikiluaq, and the Churchill, MB, to Kivalliq service. No matter where you are across the Canadian Arctic, the NEAS team of dedicated employees and our modern fleet of Inuit-owned Canadian flag vessels is ready to deliver a superior sealift experience for you. -

Social Hierarchy and Societal Roles Among the Inuit People by Caitlin Amborski and Erin Miller

Social Hierarchy and Societal Roles among the Inuit People by Caitlin Amborski and Erin Miller Markers of social hierarchy are apparent in four main aspects of traditional Inuit culture: the community as a whole, leadership, gender and marital relationships, and the relationship between the Inuit and the peoples of Canada. Due to its presence in multiple areas of Inuit everyday life, the theme of social hierarchy is also clearly expressed in Inuit artwork, particularly in the prints from Kinngait Studios of Cape Dorset and in sculptures. The composition of power in Inuit society is complex, since it is evident on multiple levels within Inuit culture.1 The Inuit hold their traditions very highly. As a result, elders play a crucial role within the Inuit community, since they are thought to be the best source of knowledge of the practices and teachings that govern their society. Their importance is illustrated by Kenojuak Ashevak’s print entitled Wisdom of the Elders, which she devotes to this subject.2 She depicts a face wearing a hood from a traditional Inuit jacket in the center of the composition with what appears to be a yellow aura, and contrasting red and green branches radiating from the hood. Generally, the oldest family members are looked upon as elders because their age is believed to reveal the amount of wisdom that they hold.3 One gets the sense that the person portrayed in this print is an elder, based on the wrinkles that are present around the mouth. In Inuit society, men and women alike are recognized as elders, and this beardless face would seem 1 Janet Mancini Billson and Kyra Mancini, Inuit Women: their powerful spirit in a century of change, (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 56. -

The Quest for the Northwest Passage

NOVA DANIA THE QUEST FOR THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE SUZANNE CARLSON With considerable envy, the seventeenth century King of Denmark, Christian IV, watched the scramble to discover the elusive passage over Polar regions to lay claim to the riches of Cathay. This article will follow the fate of Christian’s early seventeenth century New World foothold, Nova Dania, through the cartographic record, speculating on what and when the Danes might have known about the then frozen northwest passage. An essential piece in this story is the amazing tale of Jens Munk, a merchant adventurer in the King’s service. For the cyber traveler, opportunities have reached a new zenith with Google Earth (FIGURE 1). I find myself cruising at 35,000 feet over the Alps, the Arabian Desert, up the Dania Nova Amazon, and to one of my favorite armchair destinations, FIGURE 2. JUSTUS DANCKERT’S TOTIUS AMERICAE DESCRIPTIO, the Arctic. With your AMSTERDAM, CA. 1680. VESTERGOTLANDS MUSEET, GOTHENBURG, SWEDEN Google joy stick, PART I - MAPPING NOVA DANIA you are able to glide with ease through the newly open waters With addictive zeal I searched map after map until I finally of the Northwest spotted it again: this time with the name reversed into Nova Passage. Dania (New Denmark). And there was more. Mer Cristian, Mare Christianum, or Christians Sea, depending on the Before the days of FIGURE 1. NORTHERN CANADA AND language appeared in what is now Fox Basin. Later, Nova GREENLAND. GOOGLE EARTH, 2006 satellite imaging, we Dania abandoned its Latin pretensions and became Nouvelle were content with and Denmarque and, as time went on, its location began to fascinated by maps, maps of unknown exotic places, maps wander—north into Buttons Bay, west into the interior, and showing nations or would-be empires. -

Contemporary Inuit Drawing

Cracking the Glass Ceiling: Contemporary Inuit Drawing Nancy Campbell A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ART HISTORY, YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO. January 2017 © Nancy Campbell, 2017 Abstract The importance of the artist’s voice in art historical scholarship is essential as we emerge from post-colonial and feminist cultural theory and its impact on curation, art history, and visual culture. Inuit art has moved from its origins as an art representing an imaginary Canadian identity and a yearning for a romantic pristine North to a practice that presents Inuit identity in their new reality. This socially conscious contemporary work that touches on the environment, religion, pop culture, and alcoholism proves that Inuit artists can respond and are responding to the changing realities in the North. On the other side of the coin, the categories that have held Inuit art to its origins must be reconsidered and integrated into the categories of contemporary art, Indigenous or otherwise, in museums that consider work produced in the past twenty years to be contemporary as such. Holding Inuit artists to a not-so-distant past is limiting for the artists producing art today and locks them in a history that may or may not affect their work directly. This dissertation examines this critical shift in contemporary Inuit art, specifically drawing, over the past twenty years, known as the contemporary period. The second chapter is a review of the community of Kinngait and the role of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative in the dissemination of arts and crafts. -

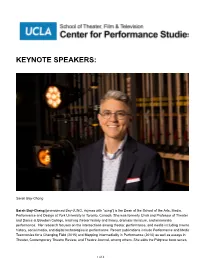

Center for Performance Studies

Sarah Bay-Cheng Sarah Bay-Cheng [pronounced Bay-JUNG, rhymes with “sung”] is the Dean of the School of the Arts, Media, Performance and Design at York University in Toronto, Canada. She was formerly Chair and Professor of Theater and Dance at Bowdoin College, teaching theater history and theory, dramatic literature, and intermedia performance. Her research focuses on the intersections among theater, performance, and media including cinema history, social media, and digital technologies in performance. Recent publications include Performance and Media Taxonomies for a Changing Field (2015) and Mapping Intermediality in Performance (2010) as well as essays in Theater, Contemporary Theatre Review, and Theatre Journal, among others. She edits the Palgrave book series, 1 of 4 Avant-Gardes in Performance and is a co-host for On TAP: A Theatre and Performance Studies podcast. Bay- Cheng frequently lectures internationally and in 2015 was a Fulbright Visiting Scholar at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. She has served on the boards of Performance Studies international and the Association for Theatre i Higher Education, and is currently a member of the Executive Committee for the American Society for Theatre Research (ASTR). Bay-Cheng has also worked as a director and dramaturg with particular interest in intermedial collaborations and a fondness for puppetry. Daphne A. Brooks (https://afamstudies.yale.edu/people/daphne- brooks) Daphne A. Brooks is William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of African American Studies, American Studies, Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies & Music at Yale University. She is the author of two books: Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850-1910 (Durham, NC: Duke UP), winner of The Errol Hill Award for Outstanding Scholarship on African American Performance from ASTR, and Jeff Buckley's Grace (New York: Continuum, 2005). -

Celebrating 30 Years of Supporting Inuit Artists

Celebrating 30 Years of Supporting Inuit Artists Starting on June 3, 2017, the Inuit Art Foundation began its 30th Similarly, the IAF focused on providing critical health and anniversary celebrations by announcing a year-long calendar of safety training for artists. The Sananguaqatiit comic book series, as program launches, events and a special issue of the Inuit Art Quarterly well as many articles in the Inuit Artist Supplement to the IAQ focused that cement the Foundation’s renewed strategic priorities. Sometimes on ensuring artists were no longer unwittingly sacrificing their called Ikayuktit (Helpers) in Inuktut, everyone who has worked health for their careers. Though supporting carvers was a key focus here over the years has been unfailingly committed to helping Inuit of the IAF’s early programming, the scope of the IAF’s support artists expand their artistic practices, improve working conditions extended to women’s sewing groups, printmakers and many other for artists in the North and help increase their visibility around the disciplines. In 2000, the IAF organized two artist residencies globe. Though the Foundation’s approach to achieving these goals for Nunavik artists at Kinngait Studios in Kinnagit (Cape Dorset), NU, has changed over time, these central tenants have remained firm. while the IAF showcased Arctic fashions, film, performance and The IAF formed in the late 1980s in a period of critical transition other media at its first Qaggiq in 1995. in the Inuit art world. The market had not yet fully recovered from The Foundation’s focus shifted in the mid-2000s based on a the recession several years earlier and artists and distributors were large-scale survey of 100 artists from across Inuit Nunangat, coupled struggling. -

Annual Report 2019/20 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020

ᕿᑭᖅᑖᓗᒃ ᑯᐊᐳᕆᓴᓐ ᓇᒻᒥᓂᕐᑯᑎᖕᒋᓪᓗ QIKIQTAALUK CORPORATION & Group of Companies Annual Report 2019/20 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020 Chairman’s Message 1 President’s Message 2 Ludy Pudluk 3 About Qikiqtaaluk Corporation 4 Company Profile 4 Qikiqtani Region 5 Company Chart 6 Board of Directors 7 2019-2020 Highlights 8 PanArctic Communications 8 QC Fisheries Research Vessel 9 Inuit Employment and Capacity Building 10 Community Investment and Sponsorships 11 Scholarships 11 QIA Dividend 12 Community Investment Program 12 Event Sponsorship 13 Wholly Owned Subsidiary Activity Reports 15 Fisheries Division Activity Report 15 Qikiqtaaluk Fisheries Corporation 18 Qikiqtani Retail Services Limited 20 Qikiqtaaluk Business Development Corporation 22 Qikiqtaaluk Properties Inc. 24 Nunavut Nukkiksautiit Corporation 26 Qikiqtani Industry Ltd. 28 Aqsarniit Hotel and Conference Centre Inc. 31 Akiuq Corporation 33 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation Group of Companies 34 Other Wholly Owned Subsidiaries 34 Majority Owned Joint Ventures 34 Joint Venture Partnerships 35 Affiliations 36 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020 | Chairman’s Message Welcome to the 2019-2020 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation Annual Report. This past year was a time of focus and dedication to ensuring Qikiqtaaluk Corporation’s (QC) ongoing initiatives were progressed and delivered successfully. In overseeing the Corporation and its eleven wholly owned companies, we worked diligently to ensure every decision is in the best interest of Qikiqtani Inuit and promotes the growth of the Corporation. On behalf of the Board, we would like to share our sadness and express our condolences on the passing of longstanding QC Board member and friend, Ludy Pudluk. Ludy was a Director on QC’s Board for over two decades. -

Death and Life for Inuit and Innu

skin for skin Narrating Native Histories Series editors: K. Tsianina Lomawaima Alcida Rita Ramos Florencia E. Mallon Joanne Rappaport Editorial Advisory Board: Denise Y. Arnold Noenoe K. Silva Charles R. Hale David Wilkins Roberta Hill Juan de Dios Yapita Narrating Native Histories aims to foster a rethinking of the ethical, methodological, and conceptual frameworks within which we locate our work on Native histories and cultures. We seek to create a space for effective and ongoing conversations between North and South, Natives and non- Natives, academics and activists, throughout the Americas and the Pacific region. This series encourages analyses that contribute to an understanding of Native peoples’ relationships with nation- states, including histo- ries of expropriation and exclusion as well as projects for autonomy and sovereignty. We encourage collaborative work that recognizes Native intellectuals, cultural inter- preters, and alternative knowledge producers, as well as projects that question the relationship between orality and literacy. skin for skin DEATH AND LIFE FOR INUIT AND INNU GERALD M. SIDER Duke University Press Durham and London 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sider, Gerald M. Skin for skin : death and life for Inuit and Innu / Gerald M. Sider. pages cm—(Narrating Native histories) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5521- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5536- 6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Naskapi Indians—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador— Social conditions.