Making the Most of London's Waterways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Management, Labour Relations and Community Building at the East India Company's Blackwall Dockyard, 1600-1657 ABSTRA

Corporate Management, Labour Relations and Community Building at The East India Company’s Blackwall Dockyard, 1600-1657 ABSTRACT This essay offers a social history of the labour relations established by the English East India Company at its Blackwall Dockyard in East London from 1615-1645. It uses all of the relevant evidence from the Company’s minute books, printed bye-laws, and petitions to the Company to assemble a full account of the relationships formed between skilled and unskilled workers, managers, and company officials. Challenging other historians’ depictions of early modern dockyards as sites for class confrontation, this essay offers a more agile account of the hierarchies within the yard to suggest how and why the workforce used its considerable power to challenge management and when and why it was successful in doing so. Overall, the essay suggests that the East India Company developed and prioritised a broader social constituency around the dockyard over particular labour lobbies to pre-empt accusations that it abdicated its social responsibilities. In this way, the company reconciled the competing interests of profit (as a joint stock company with investors) and social responsibility by - to some extent - assuming the social role of its progenitor organisations – the Livery Company and the borough corporation. Early modern trading corporations were social institutions as well as commercial ones. As large employers, both at home and overseas, they sought to maintain positive labour relations with management practices that were responsive, adaptive and positioned the company as an integral and beneficial component of local communities. In doing so they were able to make the case for their corporate privileges with reference to the employment opportunities they provided and their positive contribution to society. -

Blackwall Reach to Bugsbys Reach

2 2 3 A L P Castle Wharf 6 06 33 52 32 8 32 Castle Wharf 02 3 0.6 5 0 (Bonds Wharf) 3 04 0°0.'5W'W P 3 I 0 L 8 .4 G 0. R 3 I M NB 0.2 S 4 0 M 3 4 0.1 E W 2 0°0'E S 6 0.1 Herc 0.2 O ules 0 R 27 8 0.3 C Wharf 3 H 0.4 2 6 A 3 9 0.5'E R 0°0'E D Leamouth 0 0.6 0.7 P 1 J Ingram 8 O Perk 3 L ins 0.8 H Wharf 2 A N 6 C 0.9 S Eas & Co Ltd 3 M E t I 3 U n d E 3 EN ia D 7 L V oc T A ks 0°1 T 4 'E POR H NEW 1.1 M 2 1 Tide Deta E 3 1.2 ils, referred to levels W 33 1 at S 1 Ordnance 6 2 1.3 West India Chart 6 23 1.4 Dock Entrance: 0 72 Datum Datum 1 15 Highest R 22 5 st Reecocrodredd (195 J 3 45 ed (139)53) A 6 30.5'N 5.25 M 39 4 51°30'N 8 E .60 Highest A S 4 est Asstrtorononmomic Tide T ic Tide O 0 4.40 7 W Orc 3 7 M .75 N hard Wh Mean H ar 4 an Higighh W Wataetre Sr pSripnrgins g W f 2 s A 2 1 3.87 7.22 Y 0 13 Mea Pur d 3 8 Meann H Higighh W Wataetrer a Foods 06 2 3.25 e Shell U 2 2 Mean 6.60 s .K. -

White Swan Public House, Yabsley Street, Blackwall, London Borough of Tower Hamlets

White Swan Public House, Yabsley Street, Blackwall, London Borough of Tower Hamlets An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment for St James Homes Ltd by Lisa‐Maree Hardy Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code WSL02/54 June 2002 White Swan Public House, Yabsley Street, Blackwall An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment by Lisa-Maree Hardy Report 02/54 Introduction This desk-based study is an assessment of the archaeological potential of a parcel of land fronting Yabsley Street, Blackwall, London Borough of Tower Hamlets (TQ 3840 8055) (Fig. 1). The project was commissioned by Mr Andy Ainsworth of St James Homes (North Thames Region), Marlborough House, 298 Regents Park Road, Finchley, London N3 2UA and comprises the first stage of a process to determine the presence/absence, extent, character, quality and date of any archaeological remains which may be affected by redevelopment of the area. Site description, location and geology A site visit was made on 11th June, 2002, in order to determine the current land use on the site. The site comprises an irregular shaped parcel of land, with frontage to Blackwall Way, Yabsley Street and Preston’s Road, Blackwall. The site is bounded to the south by Yabsley Street and land currently used as a holding yard and a car park. To the west of the site is Preston’s Road, a main thoroughfare linking Poplar with the Isle of Dogs, and to the east, Blackwall Way and a new residential development. The site is bounded to the north by residences and an air intake shaft to the Blackwall Tunnel. -

Chronicles of Blackwall Yard

^^^VlBEDi^,^ %»*i?' ^^ PART • 1 University of Calil Southern Regioi Library Facility^ £x Libris C. K. OGDEN ^^i^-^-i^^ / /st^ , ^ ^ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES CHRONICLES OF BLACKWALL YARD PART I. BY HENRY GREEN and ROBERT WIGRAM. " Nos .... nee gravem Pelidcc stomaclium, cedere nescii. Nee ciirsus diiplicU per mare U/ixei, Nee sava»i Pelopis domiim Coiiannir, teniies grandia ; . " Hor., Lib. I.. Car. IV. PUBLISHED BY WHITEHEAD, MORRIS AND LOWE. lS8l. 2>0l @^ronicIc6 of '^iackxxxxii ^ar6. AT the time when our Chronicles commence, the Hamlet of Poplar and Blackwall, in which the dockyard whose history we propose to sketch is situated, was, together with the Hamlets of Ratclifie and Mile End, included in the old Parish of Stebunhethe, now Stepney, in the hundred of Ossulston. The Manor of Stebunhethe is stated in 1067. the Survey of Doomsday to have been parcel of the ancient demesnes of the Bishopric of London. It is there described as of large extent, 1299. and valued at ^48 per annum! In the year 1299 a Parliament was held Lyson's En- by King Edward I., at Stebunhethe, in the house of Henry Walleis, virons^ Mayor of London, when that monarch confirmed the charter of liberties. p. 678. Stebunhethe Marsh adjoining to Blackwall, which was subsequently called Stows but the Isle of years after this Annals. the South Marsh, now Dogs, was some described as a tract of land lying within the curve the P- 319- which Thames forms between Ratcliffe and Blackwall. Continual reference is made in local records to the embankments of this marsh, and to the frequent 1307- breaches in them. -

THE BLACKWALL FRIGATES Digitized by Tine Internet Archive

BASIL LUBBO THE BLACKWALL FRIGATES Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/blackwallfrigatesOOIubb THE BLACKWALL FRIGATES BY BASIL LUBBOCK Author of "The Ch\na Clippers"; "The Colonial Clippers, "Round the Horn before the Mast"; "Jack Derringer, " a Tale of Deep Water" ; and Deep Sea Warriors" WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND PLANS GLASGOW JAMES BROWN S- SON (Glasgow) Ltd., Publishers 52 TO 58 Darnley Street 1922 v/r Dedication Dedicated to the Blackwall Midshipmite. PREFACE The Blackwall frigates form a connecting link between the lordly East Indiaman of the Honourable John Company and the magnificent P. & O. and Orient liners of the present day. They were first-class ships—well-run, happy ships, and the sailor who started his sea life as a midshipman aboard a Blackwaller looked back ever afterwards to his cadet days as the happiest period of his career. If discipline was strict, it was also just. The train- ing was superb, as witness the number of Blackwall midshipmen who reached the head of their profession and distinguished themselves later in other walks of life. Indeed, as a nursery for British seamen, we shall never see the like of these gallant little frigates. The East still calls, yet its glamour was twice as alluring, its vista twice as romantic, in the days of sail; and happy indeed was the boy who first saw the shores of India from the deck of one of Green's or Smith's passenger ships. Fifty years ago, the lithographs of the celebrated Blackwall liners to India and Australia could be bought at any seaport for a few shillings. -

The General Steam Navigation Company C.1850-1913: a Business History

ERB^C£ USE ONLY The General Steam Navigation Company c.1850-1913: A business history Robert Edward Forrester ffi A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a very considerable debt to my supervisors, Professor Sarah Palmer and Professor Roger Knight of The Greenwich Maritime Institute for, first of all, accepting me as a research student and for their stimulating support, direction and encouragement in the lengthy preparation of this study. The always friendly staff of the Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich were unfailingly helpful during the many hours spent researching archive material, as were the library staff at the Rural History Centre, The University of Reading. They assisted me greatly with my research into the importation of live animals, one of the more unexpected diversions of the work. Other libraries were also extremely helpful, notably that at the London School of Economics, and my local library which produced remarkably swiftly, through its inter-library service, a wide range of publications. Most importantly, throughout the extended period of research and writing my wife has been an constant source of support and encouragement as have my two daughters. Without them this project would never have been embarked upon. n ABSTRACT This thesis concerns the history of the General Steam Navigation Company from 1850 to 1913, immediately prior to the First World War. Established as a joint-stock company in 1824, this London-based shipowner operated a range of steamship liner services on coastal and near-Continent routes and, from the 1880s, to the Mediterranean. -

In the Shadow of Empire: Rethinking Local Agency in Tower Hamlets at the Fin De Siècle Joseph Oliver Turner MA by Research Univ

In the Shadow of Empire: Rethinking local agency in Tower Hamlets at the fin de siècle Joseph Oliver Turner MA by Research University of York History May, 2018 Abstract Through an examination of how local politicians developed, cultivated and maintained relationships with their constituents and national parties, this thesis will explore the ways that the contingent and contested nature of popular politics impacted on the daily lives of the working classes in Tower Hamlets, from 1895 to 1906. Through a synthesis of election material, local newspapers and recollections this thesis will explore popular political and economic practices and their articulation at ground level, using the Boer War, 1899 - 1902, and The Tariff Reform Campaign, 1903 – 1906, as case studies to highlight the uncertainty of politics at this time. These studies will highlight how individual agency within political parties negotiated and asked for power from the communities they represented. Simultaneously, it will analyse the agentic political culture which was inherent within working-class constituencies in Tower Hamlets, to highlight how local politicians reconstructed a popular image based on their local networks and relationships. The thesis will conclude by arguing that the interaction between politicians and their constituents were more complicated than some historians have argued, as national and imperial politics were mediated through the prism of working-class aspirations and concerns. The aim of this thesis is to paint a picture of a more vibrant political scene, where national and imperial politics were constructed from ground level, and working-class agentic political culture had a larger impact on the course of British history. -

Incident on the River Thames, Individual Sections of the River Are Identified by Using the Grid Mobilising Scheme (Refer to Appendix 2)

Policy | Procedure Incidents on the River Thames New policy number: 260 Old instruction number: Issue date: 17 November 1993 Reviewed as current: 11 November 2019 Owner: Assistant Commissioner, Operational Policy Responsible work team: Rescue Team Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 2 Legislation .................................................................................................................... 4 3 Hazards ........................................................................................................................ 4 4 Planning ....................................................................................................................... 5 5 Mobilising .................................................................................................................... 8 6 En-route ....................................................................................................................... 9 7 On arrival ................................................................................................................... 10 8 Operational procedures ................................................................................................. 11 9 Associated policies ....................................................................................................... 16 Appendix 1 - Key point summary – incidents on the River Thames ............................................... 17 Appendix -

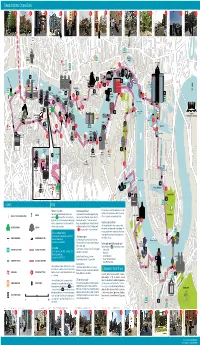

Cycle Paths Apartand Public Highways

A B C D E F G H I J K L M St Paul’s S ’ T N L E C A omm G N ercia l E Road A R C Limehouse M d i C R n a Shadwell o h n ST PAUL’S r c i n n L e LIMEHOUSELIMEHOU E o a I s n r M CATHEDRAL wall s ros B BASINBASI E C S Cab H le St t le Stree Cab reet r t eferry Ro ONE CANADA e Hors a O N e d Fenchurch St t U MILLENNIUM BRIDGE MILLENNIUM a SQUARE Q R r S r t o ee o E Tower a Str w Street le d KING EDWARD VII Gateway Cab L Blackfriars Bridge Tower Hill MEMORIAL PARK I N t Na The Highway S rro K w s S i 40 t ree . m . 39 . l t . l i . Tow Highway . 37 HSBC er H . The . a . GABRIEL’S WHARF l . 38 . 3 . G . SHADWELL V . 43 a Bankside . E u TOBACCO BASIN . a THE . g . s B . 21 . il . l . i . t n . Pier g S h sg . a te . Rd . DOCK . m a . GRAPES i . t n . h ld ie GLOBE WHARF . f . West India . S R W . 42 . 44 a . Quay . y n Cres g ce . rei T ve nt o . S Southwark Bridge THE LONDON A ST KATHERINE’S . P . t 7 y a . g . e TOWER OF LONDON a a BICYCLE S DOCK N 1 . 41 n T . Rotherhithe Street . -

Granaries, Shipyards and Wharves

Maritime Rotherhithe HISTORY WALK WALK B: SHIPYARDS, GRANARIES AND WHARVES by Stuart Rankin TOP: LOOKING ACROSS TO THE DOG & DUCK STAIRS FROM THE SITE OF BLIGHT’S YARD. BELOW: SHIP UNDER REPAIR AT MILLS & KNIGHT LTD., NELSON DOCK IN THE 1940S. COVER IMAGES: TOP: THE MASSIVE FORMER GRAIN WAREHOUSE AT GLOBE WHARF. BOTTOM: THE HOWLAND GREAT WET DOCK C1710, SHOWING THE SHIPYARDS EITHER SIDE OF THE ENTRANCE. The walk in this booklet is presented as an itinerary exploring the maritime history of Rotherhithe. The theme of Walk “B” is “Shipyards, Granaries and Wharves”; it begins at Surrey Quays underground station, and follows the south side of Greenland Dock to the River Thames. The route then follows the river upstream, visiting the sites of several shipyards, where vessels of international historic significance were constructed, passing some of the imposing granaries, and the wharves, which eventually were to replace shipbuilding as the main industrial activity on this stretch of the river. It ends at the Surrey Entrance Lock, with the option of a short walk to Rotherhithe Station, or of taking a bus for a quicker return. Surrey Quays station to Surrey Entrance Lock can be walked in 1 2 /2 to 3 hours. Once having left Greenland Dock, this walk offers some flexibility for those who prefer a shorter outing (or discover that the weather is not going to be quite as good as was hoped!). At no point is the later part of the route more than a few minutes walk from a bus stop. Few areas of London have undergone as much change from war damage, post war reconstruction and redevelopment in the 1980s and 1990s. -

A Walk from Tower Hill to Wapping

A walk from Tower Hill to Wapping Updated: 7 August 2019 Length: About 2¼ miles Duration: Around 3 hours NOTES 1. This walk can be treated as the first leg of a five-hour walk from Tower Hill through Wapping and Limehouse to Canary Wharf. The introduction below takes in both halves of the full-length walk 2. Whilst it may be obvious, I must point out that things might have changed since I wrote this walk. This is particularly the case with the Thames Path – access points that were previously open can suddenly close, particularly when building work is taking place. London, and the riverside in the docklands in particular, are continually changing, so buildings and sights described may differ. As always, I appreciate any comments or suggestions from those who do the walk, particularly about any changes that have taken place so I can keep the walk updated. GETTING HERE The walk starts at Tower Hill tube station – which is on the Circle and District lines. Buses Number 15 stops adjacent to Tower Hill Underground station, opposite the Tower of London. The service runs from Trafalgar Square/Charing Cross station, St Paul’s Cathedral, Bank station/Queen Victoria Street and Monument station. (For details of other nearby bus routes check the Transport for London website.) 1 Route map 1 STARTING THE WALK Upon arriving at the station exit through the ticket barrier, turn left and walk down the steps on the right, passing the lower entrance to the station, and continue towards the underpass. (However, if you leave the platform via a different exit and emerge from the newer entrance/exit then simply turn right and walk down the steps.) As you walk down the steps, the statue you pass on your left is believed to be of the Roman emperor Trajan (98–117 AD) and behind it are parts of the original Roman wall that at one time encircled the City of London. -

The East India Docks Rob Smith

The East India Docks Rob Smith Cornelis Ketel “Sir Martin Frobisher” 1577 Walter Raleigh’s House Blackwall Sir James Lancaster Blackwall Yard East Indiamen in a Gale, by Charles Brooking, c. 1759 Perry’s Brunswick Dock Perry’s Dock at Blackwall 1799 William Anderson “Cavalry Embarking at Blackwall” 1793 East India Docks 1806 John Rennie (Senior) Works on London Docks East India Docks West India Docks Hull, Liverpool Docks,Dublin Waterloo Bridge London Bridge (built by son) Southwark Bridge (old) Caen Hill Locks in Devizes Ralph Walker 1749-1824 Works on West India Dock Thames and Medway Canal East London Waterworks Opposed to the use of steam engines Rennie and Walker have to make bricks on site 9 million required Temporary workers accommodation needs to be built Shortage of builders Bricklayers don’t want to work near river for fear of press gang August 1806 dock opened to singing of Rule Britannia Admiral Gardiner first ship in the dock East India company ships are big – 750 tons Often loaded at Greenhithe in Kent Unloaded at Blackwall onto lighters East India Ship Repulse in East India Dock 1820 San Martin (ex-Cumberland), Lautaro, Chacabuco, and Araucano by Thomas Somerscales Thomas Goldsworth Dutton “East Indiamen Madagascar” 1840 East India Dock • Quayside but no warehousing • Imports – silk • Spices • Persian carpets • Tea • Home to the Cutty Sark 'Malacca': Departure of Messrs Green's Frigate 'Malacca' for Bombay from Brunswick Pier, Blackwall, 26 December 1849 Richard Ball Spencer “SS Great Britain at Brunswick Wharf Blackwall” Charles Napier Henry “Blackwall” 1872 Frances McDonald Building the Mulberry Harbour, London Docks 1944 http://footprintsoflondon.com.