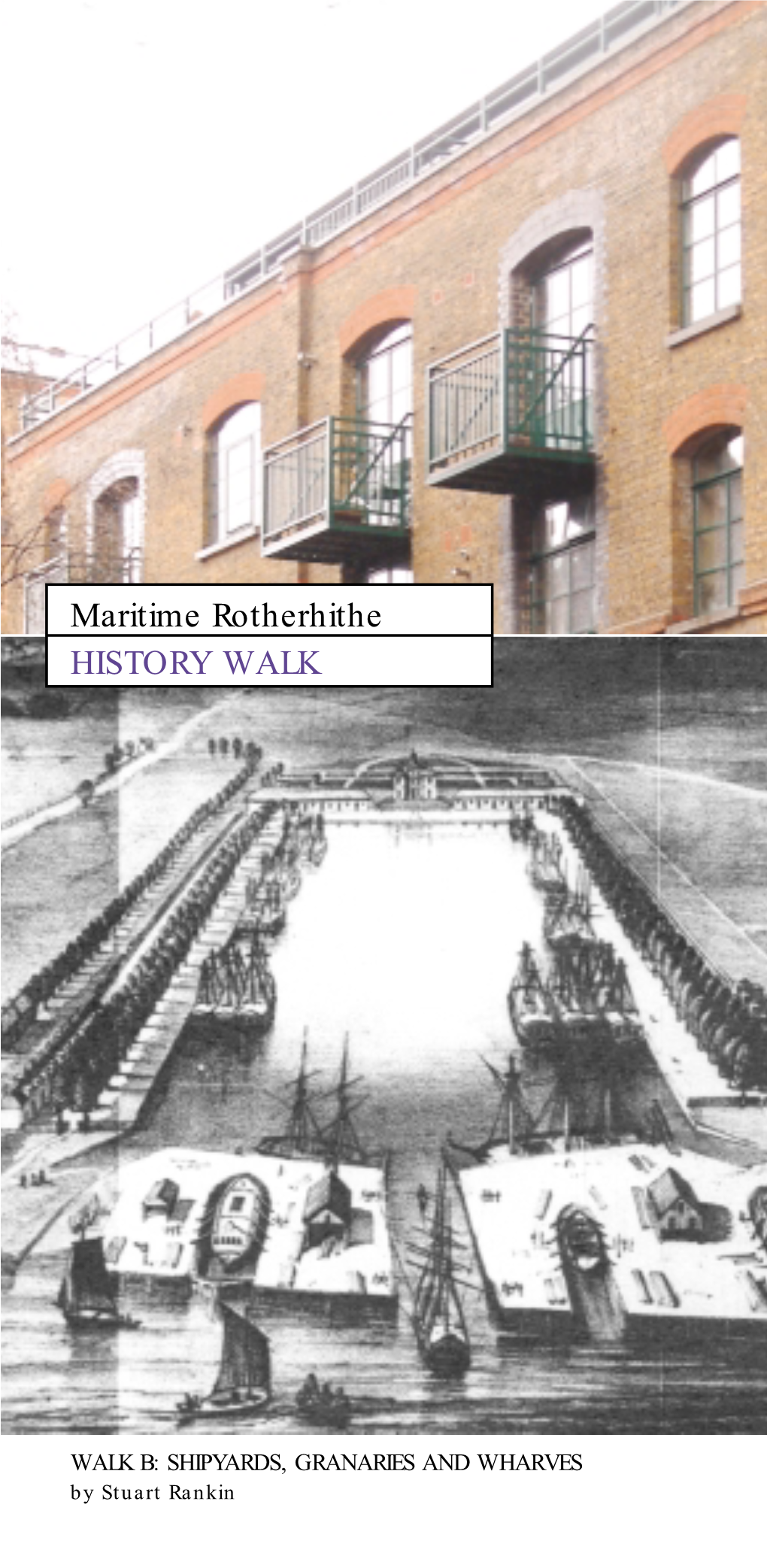

Granaries, Shipyards and Wharves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARCHITECTURE, POWER, and POVERTY Emergence of the Union

ARCHITECTURE, POWER, AND POVERTY Emergence of the Union Workhouse Apparatus in the Early Nineteenth-Century England A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Gökhan Kodalak January 2015 2015, Gökhan Kodalak ABSTRACT This essay is about the interaction of architecture, power, and poverty. It is about the formative process of the union workhouse apparatus in the early nineteenth-century England, which is defined as a tripartite combination of institutional, architectural, and everyday mechanisms consisting of: legislators, official Poor Law discourse, and administrative networks; architects, workhouse buildings, and their reception in professional journals and popular media; and paupers, their everyday interactions, and ways of self-expression such as workhouse ward graffiti. A cross-scalar research is utilized throughout the essay to explore how the union workhouse apparatus came to be, how it disseminated in such a dramatic speed throughout the entire nation, how it shaped the treatment of pauperism as an experiment for the modern body-politic through the peculiar machinery of architecture, and how it functioned in local instances following the case study of Andover union workhouse. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Gökhan Kodalak is a PhD candidate in the program of History of Architecture and Urbanism at Cornell University. He received his bachelor’s degree in architectural design in 2007, and his master’s degree in architectural theory and history in 2011, both from Yıldız Technical University, Istanbul. He is a co-founding partner of ABOUTBLANK, an inter-disciplinary architecture office located in Istanbul, and has designed a number of award-winning architectural and urban design projects in national and international platforms. -

AMRC Journal Volume 21

American Music Research Center Jo urnal Volume 21 • 2012 Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder The American Music Research Center Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Dominic Ray, O. P. (1913 –1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music Eric Hansen, Editorial Assistant Editorial Board C. F. Alan Cass Portia Maultsby Susan Cook Tom C. Owens Robert Fink Katherine Preston William Kearns Laurie Sampsel Karl Kroeger Ann Sears Paul Laird Jessica Sternfeld Victoria Lindsay Levine Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Kip Lornell Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25 per issue ($28 outside the U.S. and Canada) Please address all inquiries to Eric Hansen, AMRC, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. Email: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISBN 1058-3572 © 2012 by Board of Regents of the University of Colorado Information for Authors The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing arti - cles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and proposals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (exclud - ing notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, Uni ver - sity of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. Each separate article should be submitted in two double-spaced, single-sided hard copies. -

Making the Most of London's Waterways

MAKING THE MOST OF LONDON’S WATERWAYS ABOUT FUTURE OF LONDON Future of London helps build better cities through knowledge, networks and leadership – across disciplines, organisations and sectors. We are the capital’s independent network for regeneration, housing, infrastructure and economic development practitioners, with 4,000+ professionals using FoL as a hub for sector intelligence, connection and professional development, and a mandate to prepare the next wave of cross-sector city leaders. PROJECT TEAM Amanda Robinson, Oli Pinch, Nicola Mathers, Aydin Crouch Report written and designed by: Amanda Robinson Report edited by: Charli Bristow, Nicola Mathers, Lisa Taylor PROJECT PARTNERS CORE PARTNERS We are grateful to Arup, Avison Young, Pollard Thomas Edwards and Hadley Property Group for supporting this work. Arup is an independent firm of designers, planners, engineers, consultants and technical specialists offering a broad range of professional services. Avison Young is the world’s fastest growing real estate business. Pollard Thomas Edwards specialises in the creation of new neighbourhoods and the revitalisation of old ones. Their projects embrace the whole spectrum of residential development and other essential ingredients which make our cities, towns and villages into thriving and sustainable places. Hadley Property Group is a developer which specialises in progressive, sustainable approaches to the delivery of much-needed housing in Greater London and other major UK cities. REPORT PARTNER EVENT PARTNER The Canal & River Trust kindly The Port of London Authority kindly provided event and report support. provided event support. Published December 2019 © Future of London 2011 Ltd. Cover photo of Packington Estate kindly supplied by Pollard Thomas Edwards © Tim Crocker. -

The Messenger

THE MESSENGER MARCH 2015 www.moulshammethodist.org.uk Welcome to the Messenger with news, views and information about the activities of Moulsham Lodge Methodist Church. We are here to offer Christ’s Life to Our World: Our values: Respecting the dignity and worth of all Demonstrating love, forgiveness and healing Calling out the best in all Practising integrity of life and faith Being a safe place for struggle and engagement Church Information For information about baptisms, weddings and funerals Please contact: Rev Mike Crockett 01245 262595 e-mail: [email protected] Important Editorial Information Internet The Messenger will be displayed, in full, on our web site each month. It is your responsibility to ensure that you have obtained the correct permissions when you submit items written by a third person, and that we acknowledge them, or items that include personal contact details or photographs. However, we will always accept Christian names only, or none, for photographs of children. When you send items for publication please ensure they are in Word (A4 size) as an attachment or embedded into an e-mail so I can cut and paste accordingly, as other formats are not easily transferable. Thank you. From the Editor, Happy Birthday! Moulsham Methodist celebrates its 53rd birthday on March 1st! Please note the changed date for the Church Council (page 5) This edition is thinner than usual because of the lack of items you wanted included! Please think what you can send for the April Messenger. Personal news, news of your organisation, Lent group thoughts, Easter thoughts and poems?? Editor: Clive Pickett [email protected] 01245 267459 The deadline for items for the April edition is March 17th. -

Corporate Management, Labour Relations and Community Building at the East India Company's Blackwall Dockyard, 1600-1657 ABSTRA

Corporate Management, Labour Relations and Community Building at The East India Company’s Blackwall Dockyard, 1600-1657 ABSTRACT This essay offers a social history of the labour relations established by the English East India Company at its Blackwall Dockyard in East London from 1615-1645. It uses all of the relevant evidence from the Company’s minute books, printed bye-laws, and petitions to the Company to assemble a full account of the relationships formed between skilled and unskilled workers, managers, and company officials. Challenging other historians’ depictions of early modern dockyards as sites for class confrontation, this essay offers a more agile account of the hierarchies within the yard to suggest how and why the workforce used its considerable power to challenge management and when and why it was successful in doing so. Overall, the essay suggests that the East India Company developed and prioritised a broader social constituency around the dockyard over particular labour lobbies to pre-empt accusations that it abdicated its social responsibilities. In this way, the company reconciled the competing interests of profit (as a joint stock company with investors) and social responsibility by - to some extent - assuming the social role of its progenitor organisations – the Livery Company and the borough corporation. Early modern trading corporations were social institutions as well as commercial ones. As large employers, both at home and overseas, they sought to maintain positive labour relations with management practices that were responsive, adaptive and positioned the company as an integral and beneficial component of local communities. In doing so they were able to make the case for their corporate privileges with reference to the employment opportunities they provided and their positive contribution to society. -

Blackwall Reach to Bugsbys Reach

2 2 3 A L P Castle Wharf 6 06 33 52 32 8 32 Castle Wharf 02 3 0.6 5 0 (Bonds Wharf) 3 04 0°0.'5W'W P 3 I 0 L 8 .4 G 0. R 3 I M NB 0.2 S 4 0 M 3 4 0.1 E W 2 0°0'E S 6 0.1 Herc 0.2 O ules 0 R 27 8 0.3 C Wharf 3 H 0.4 2 6 A 3 9 0.5'E R 0°0'E D Leamouth 0 0.6 0.7 P 1 J Ingram 8 O Perk 3 L ins 0.8 H Wharf 2 A N 6 C 0.9 S Eas & Co Ltd 3 M E t I 3 U n d E 3 EN ia D 7 L V oc T A ks 0°1 T 4 'E POR H NEW 1.1 M 2 1 Tide Deta E 3 1.2 ils, referred to levels W 33 1 at S 1 Ordnance 6 2 1.3 West India Chart 6 23 1.4 Dock Entrance: 0 72 Datum Datum 1 15 Highest R 22 5 st Reecocrodredd (195 J 3 45 ed (139)53) A 6 30.5'N 5.25 M 39 4 51°30'N 8 E .60 Highest A S 4 est Asstrtorononmomic Tide T ic Tide O 0 4.40 7 W Orc 3 7 M .75 N hard Wh Mean H ar 4 an Higighh W Wataetre Sr pSripnrgins g W f 2 s A 2 1 3.87 7.22 Y 0 13 Mea Pur d 3 8 Meann H Higighh W Wataetrer a Foods 06 2 3.25 e Shell U 2 2 Mean 6.60 s .K. -

Empires of the Silk Road: a History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze

EMPIRES OF THE SILK ROAD A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present 5 CHRISTOPHER I. BECKWITH PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2009 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cata loging- in- Publication Data Beckwith, Christopher I., 1945– Empires of the Silk Road : a history of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the present / Christopher I. Beckwith. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 691- 13589- 2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Asia, Central–History. 2. Europe, Eastern—History. 3. East Asia—History. 4. Middle East—History. I. Title. DS329.4.B43 2009 958–dc22 2008023715 British Library Cata loging- in- Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Minion Pro. Printed on acid- free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 CONTENTS 5 preface vii a c k n o w l e d g m e n t s x v abbreviations and sigla xvii introduction xix prologue: The Hero and His Friends 1 1 Th e Chariot Warriors 29 2 Th e Royal Scythians 58 3 Between Roman and Chinese Legions 78 4 Th e Age of Attila the Hun 93 5 Th e Türk Empire 112 6 Th e Silk Road, Revolution, and Collapse 140 7 Th e Vikings and Cathay 163 8 Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Conquests 183 9 Central Eurasians Ride to a Eu ro pe an Sea 204 10 Th e Road Is Closed 232 11 Eurasia without a Center 263 12 Central Eurasia Reborn 302 epilogue: Th e Barbarians 320 appendix a: Th e Proto- Indo- Eu ro pe ans and Th eir Diaspora 363 appendix b: Ancient Central Eurasian Ethnonyms 375 endnotes 385 bibliography 427 index 457 This page intentionally left blank PREFACE 5 Th is book presents a new view of the history of Central Eurasia and the other parts of the Eurasian continent directly involved in Central Eurasian history. -

Portland Daily Press: August 27,1873

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 1863. YOL. 23. WEDNESDAY MORNING, AUGUST 27, 1873. TERMS $8.00 12._PORTLAND PER ANNUM IN ADYANCE THF PORTLAND DAILY PRESS EDUCATIONAL. REAL ESTATE. WANTS, LOST, FOUND. TO LEI. hostile criticism ami wilful _____ MISCELLANEOUS. Published every excepted) by the “-- -- the misrepresentation, day (Sundays I press. and more exalted to • only the exceptional few! POBTV.AXD Pl ltLISHVNfi CO., ■To Let Boarding and Day School, F. G. Patterson's Situation Wanted. who, like himself, have proved themselves ITOUSE 49 St., arraugeu for two WEDNESDAY MORNING, AUG.27,18?3. At Portland. a competent pressman The best of referenc- Sprin families; to its 109 Exchange St. e f mis Led or unfurnished. EXTRAORDINARY equal exacting responsibilities. 12 Pine Portland. Me. BYes given. wli uP^r tenement St., Address for two weeks hole house let to our faniih if desired. au261w* that Gen. Terms: Eight Dollar** a Year in advance. Real The Premising Grant seven years Estate Bulletin. au26*3tE. M. President in New ago LOWE, care Press Office. Hampshire. to that too To Let, The belonged numerous class of out THE MAlffESTATE PRESS TITHE MisRes Symonds, will re-open their School INDUCEMENTS. President and his party lett Augusta lor Wanted. X Young Undies on No. 48 Park street, (in Block) containing on countrymen who admit more TO V.OAIV on FirM-Claw Monday 18th in a 1 boastfully than Is Thursday Morning at 32 50 a MAVPV CONVENIENT Tenement fora small family. HOUSEtbirtteu good rooms. Bath Room, Furnace ana morning Aug. speci published every THURSDAY, September ISlh. -

White Swan Public House, Yabsley Street, Blackwall, London Borough of Tower Hamlets

White Swan Public House, Yabsley Street, Blackwall, London Borough of Tower Hamlets An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment for St James Homes Ltd by Lisa‐Maree Hardy Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code WSL02/54 June 2002 White Swan Public House, Yabsley Street, Blackwall An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment by Lisa-Maree Hardy Report 02/54 Introduction This desk-based study is an assessment of the archaeological potential of a parcel of land fronting Yabsley Street, Blackwall, London Borough of Tower Hamlets (TQ 3840 8055) (Fig. 1). The project was commissioned by Mr Andy Ainsworth of St James Homes (North Thames Region), Marlborough House, 298 Regents Park Road, Finchley, London N3 2UA and comprises the first stage of a process to determine the presence/absence, extent, character, quality and date of any archaeological remains which may be affected by redevelopment of the area. Site description, location and geology A site visit was made on 11th June, 2002, in order to determine the current land use on the site. The site comprises an irregular shaped parcel of land, with frontage to Blackwall Way, Yabsley Street and Preston’s Road, Blackwall. The site is bounded to the south by Yabsley Street and land currently used as a holding yard and a car park. To the west of the site is Preston’s Road, a main thoroughfare linking Poplar with the Isle of Dogs, and to the east, Blackwall Way and a new residential development. The site is bounded to the north by residences and an air intake shaft to the Blackwall Tunnel. -

Full Beacher

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 20, Number 49 Thursday, December 16, 2004 Gladsome Sounds of Madrigal Reverberate in Chesterton by Paula McHugh Forty lords and ladies in Christmas finery compose a portion of the 100-member cast of Chesterton High School’s madrigal dinner. Some of the most delectable sights, sounds, and scents of the season materialize yearly in the “Greate Hall” at Chesterton High School’s Madrigal Dinner.. The cast of more than 100 music students can change from year to year. The banquet fare can change, too. What has not changed in more than three decades is the can- dlelit, opulent brocade and velvet polyphonic pageant that heralds the beginning of the holidays for Chestertonians and others who look forward to the colorful event. The CHS Madrigal Dinner is one of the hottest tickets in town during the Christmas season. “It’s nice that traditions like this continue,” CHS madrigal director Linda Pauli said. Linda allowed The Beacher free reign to capture impressions of the pageant during the madrigal’s final dress rehearsal. Members of the high school’s show choirs, the Sandpipers and Drifters, bedecked in Madrigal director Linda Pauli adjusts Stephen Pappas’ hat. Elizabethan finery, glided around the yet-to-be-trans- Stephen portrayed the Lord of the House. formed cafeteria as honored Lords and Ladies of the Greg Howard and Garry Seljan stood off in a corner grand feast. Serfs and hand bell choir servers dressed of the cavernous cafeteria, watching. The job of in humbler attire straddled the sidelines, waiting installing two dozen floor-to-ceiling columns, maroon for rehearsal to begin. -

Half-Hours with the Methodist Hymn-Book

HALF- HOURS WITH ‘ T H E M E T H O D I S T ’ HY MN - BOOK MARY CH A MPNE SS LONDON CH A R E L S H . KE LLY 2 CASTLE 51 CI TY R D A , . ND 2 6 PATE RNOSTE R ROW E , , . C . MY MOTHE R P R E F A C E As on eZo f the Secretaries of the Methodist - Hymn book Committee , I have been asked to write a few words of introduction to the book Miss Champn ess has compiled . I do so with the greater pleasure because of the intention which has inspired the writing . Miss Champ ness has not attempted an exhaustive account - of the new Hymn Book . That may be ex pecte d shortly from another hand and in another form . This is a more modest , and certainly a more popular, service rendered to - the Church , the class room , and the Christian home . The writer has specially desired to help local preachers and members of Wesley ll Guilds . She wi really help also a much larger circle . To know who wrote the hymns we sing , and under What circumstances they were written , and for what purpose , cannot fail to assist devotion and enrich experience . VI PREFACE A local preacher or class - leader who is familiar s with the hymns he uses , who know their origin , and at least some of their associations , will make a selection more suggestive of hol y thought , and more appropriate to the needs of the moment , than if he knew only the d wor s on the actual page . -

Chronicles of Blackwall Yard

^^^VlBEDi^,^ %»*i?' ^^ PART • 1 University of Calil Southern Regioi Library Facility^ £x Libris C. K. OGDEN ^^i^-^-i^^ / /st^ , ^ ^ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES CHRONICLES OF BLACKWALL YARD PART I. BY HENRY GREEN and ROBERT WIGRAM. " Nos .... nee gravem Pelidcc stomaclium, cedere nescii. Nee ciirsus diiplicU per mare U/ixei, Nee sava»i Pelopis domiim Coiiannir, teniies grandia ; . " Hor., Lib. I.. Car. IV. PUBLISHED BY WHITEHEAD, MORRIS AND LOWE. lS8l. 2>0l @^ronicIc6 of '^iackxxxxii ^ar6. AT the time when our Chronicles commence, the Hamlet of Poplar and Blackwall, in which the dockyard whose history we propose to sketch is situated, was, together with the Hamlets of Ratclifie and Mile End, included in the old Parish of Stebunhethe, now Stepney, in the hundred of Ossulston. The Manor of Stebunhethe is stated in 1067. the Survey of Doomsday to have been parcel of the ancient demesnes of the Bishopric of London. It is there described as of large extent, 1299. and valued at ^48 per annum! In the year 1299 a Parliament was held Lyson's En- by King Edward I., at Stebunhethe, in the house of Henry Walleis, virons^ Mayor of London, when that monarch confirmed the charter of liberties. p. 678. Stebunhethe Marsh adjoining to Blackwall, which was subsequently called Stows but the Isle of years after this Annals. the South Marsh, now Dogs, was some described as a tract of land lying within the curve the P- 319- which Thames forms between Ratcliffe and Blackwall. Continual reference is made in local records to the embankments of this marsh, and to the frequent 1307- breaches in them.