Woolwich Dockyard Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woolwich to Falconwood

Capital Ring section 1 page 1 CAPITAL RING Section 1 of 15 Woolwich to Falconwood Section start: Woolwich foot tunnel Nearest station to start: Woolwich Arsenal (DLR or Rail) Section finish: Falconwood Nearest station to finish: Falconwood (Rail) Section distance 6.2 miles plus 1.0 miles of station links Total = 7.2 miles (11.6 km) Introduction This is one of the longer and most attractive sections of the Capital Ring. It has great contrasts, rising from the River Thames to Oxleas Meadow, one of the highest points in inner London. The route is mainly level but there are some steep slopes and three long flights of steps, two of which have sign-posted detours. There is a mixture of surfaced paths, a little pavement, rough grass, and un-surfaced tracks. There are many bus stops along the way, so you can break your walk. Did you know? With many branches and There are six cafés along the route. Where the walk leaves the Thames loops, the Green Chain there are two cafés to your right in Thames-side Studios. The Thames walk stretches from the River Thames to Barrier boasts the 'View café, whilst in Charlton Park you find the 'Old Nunhead Cemetery, Cottage' café to your right when facing Charlton House. Severndroog spanning fields, parks and woodlands. As Castle has a Tea Room on the ground floor and the latter part of the walk indicated on the maps, offers the Oxleas Wood café with its fine hilltop views. much of this section of the Capital Ring follows some of the branches of The route is partially shared with the Thames Path and considerably with the Green Chain. -

Life of William Douglass M.Inst.C.E

LIFE OF WILLIAM DOUGLASS M.INST.C.E. FORMERLY ENGINEER-IN-CHIEF TO THE COMMISSIONERS OF IRISH LIGHTS BY THE AUTHOR OF "THE LIFE OF SIR JAMES NICHOLAS DOUGLASS, F.R.S." PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION 1923 CONTENTS CHAPTER I Birth; ancestry; father enters the service of the Trinity House; history and functions of that body CHAPTER II Early years; engineering apprenticeship; the Bishop Rock lighthouses; the Scilly Isles; James Walker, F.R.S.; Nicholas Douglass; assistant to the latter; dangers of rock lighthouse construction; resident engineer at the erection of the Hanois Rock lighthouse. CHAPTER III James Douglass re-enters the Trinity House service and is appointed resident engineer at the new Smalls lighthouse; the old lighthouse and its builder; a tragic incident thereat; genius and talent. CHAPTER IV James Douglass appointed to erect the Wolf Rock lighthouse; work commenced; death of Mr. Walker; James then becomes chief engineer to the Trinity House; William succeeds him at the Wolf. CHAPTER V Difficulties and dangers encountered in the erection of the Wolf lighthouse; zeal and courage of the resident engineer; reminiscences illustrating those qualities. CHAPTER VI Description of the Wolf lighthouse; professional tributes on its completion; tremor of rock towers life therein described in graphic and cheery verses; marriage. CHAPTER VII Resident engineer at the erection of a lighthouse on the Great Basses Reef; first attempts to construct a lighthouse thereat William Douglass's achievement description of tower; a lighthouse also erected by him on the Little Basses Reef; pre-eminent fitness of the brothers Douglass for such enterprises. CHAPTER VIII Appointed engineer-in-chief to the Commissioners of Irish Lights; three generations of the Douglasses and Stevensons as lighthouse builders; William Tregarthen Douglass; Robert Louis Stevenson. -

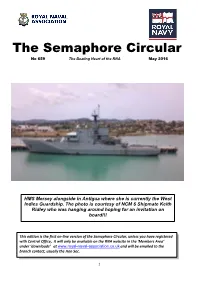

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

Sir William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs and the Institution of Engineering and Technology

Chapter 6 Sir William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs and the Institution of Engineering and Technology S. Hale Institution of Engineering and Technology, United Kingdom. Abstract Sir William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs, was a member of the Society of Telegraph Engineers and the Institution of Electrical Engineers (the precursors of the current Institu- tion of Engineering and Technology) for 36 years. Elected as the President three times, Lord Kelvin’s involvement with the institution has had a lasting effect on the Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET). His bust (Fig. 1) is displayed at the IET’s London head- quarters at Savoy Place and his portrait hangs in the lecture theatre alongside those of other engineering luminaries such as Alessandro Volta and Michael Faraday. Every year, the IET also hosts a lecture in memory of Kelvin. This chapter will explore the background to the IET, the history of Kelvin’s relationship with the Institution and the impact that he had upon the Institution as a whole. 1 Introduction The history of the IET dates back to the late nineteenth century. It was founded on 17 May 1871 as the Society of Telegraph Engineers (STE), in response to the rapid development of a new communications technology, electrical telegraphy. 1.1 Early days of telegraphy Before the advent of electrical telegraphy, transmitting communications over long distances without the use of written correspondence relied on visual aids such as fire beacons, smoke signals and flags, and later, mechanised systems such as the semaphore system created by Claude Chappé in 1793 [1]. The idea of using electricity to send messages was first proposed in the 1750s [2] but it was not until the beginning of the nineteenth century that experiments began in earnest. -

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets the Tower Was the Seat of Royal

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets The Tower was the seat of Royal power, in addition to being the Sovereign’s oldest palace, it was the holding prison for competitors and threats, and the custodian of the Sovereign’s monopoly of armed force until the consolidation of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich in 1805. As such, the Tower Hamlets’ traditional provision of its citizens as a loyal garrison to the Tower was strategically significant, as its possession and protection influenced national history. Possession of the Tower conserved a foothold in the capital, even for a sovereign who had lost control of the City or Westminster. As such, the loyalty of the Constable and his garrison throughout the medieval, Tudor and Stuart eras was critical to a sovereign’s (and from 1642 to 1660, Parliament’s) power-base. The ancient Ossulstone Hundred of the County of Middlesex was that bordering the City to the north and east. With the expansion of the City in the later Medieval period, Ossulstone was divided into four divisions; the Tower Division, also known as Tower Hamlets. The Tower Hamlets were the military jurisdiction of the Constable of the Tower, separate from the lieutenancy powers of the remainder of Middlesex. Accordingly, the Tower Hamlets were sometimes referred to as a county-within-a-county. The Constable, with the ex- officio appointment of Lord Lieutenant of Tower Hamlets, held the right to call upon citizens of the Tower Hamlets to fulfil garrison guard duty at the Tower. Early references of the unique responsibility of the Tower Hamlets during the reign of Bloody Mary show that in 1554 the Privy Council ordered Sir Richard Southwell and Sir Arthur Darcye to muster the men of the Tower Hamlets "whiche owe their service to the Towre, and to give commaundement that they may be in aredynes for the defence of the same”1. -

The Park Keeper

The Park Keeper 1 ‘Most of us remember the park keeper of the past. More often than not a man, uniformed, close to retirement age, and – in the mind’s eye at least – carrying a pointed stick for collecting litter. It is almost impossible to find such an individual ...over the last twenty years or so, these individuals have disappeared from our parks and in many circumstances their role has not been replaced.’ [Nick Burton1] CONTENTS training as key factors in any parks rebirth. Despite a consensus that the old-fashioned park keeper and his Overview 2 authoritarian ‘keep off the grass’ image were out of place A note on nomenclature 4 in the 21st century, the matter of his disappearance crept back constantly in discussions.The press have published The work of the park keeper 5 articles4, 5, 6 highlighting the need for safer public open Park keepers and gardening skills 6 spaces, and in particular for a rebirth of the park keeper’s role. The provision of park-keeping services 7 English Heritage, as the government’s advisor on the Uniforms 8 historic environment, has joined forces with other agencies Wages and status 9 to research the skills shortage in public parks.These efforts Staffing levels at London parks 10 have contributed to the government’s ‘Cleaner, Safer, Greener’ agenda,7 with its emphasis on tackling crime and The park keeper and the community 12 safety, vandalism and graffiti, litter, dog fouling and related issues, and on broader targets such as the enhancement of children’s access to culture and sport in our parks The demise of the park keeper 13 and green spaces. -

Part 4: Conclusions and Recommendations & Appendices

Twentieth Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth: Characterisation Report PART FOUR CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS The final focus of this report is to develop the local, national and international contexts of the two dockyards to highlight specific areas of future research. Future discussion of Devonport and Portsmouth as distinct designed landscapes would coherently organise the many strands identified in this report. The Museum of London Archaeology Portsmouth Harbour Hinterland Project carried out for Heritage England (2015) is a promising step in this direction. It is emphasised that this study is just a start. By delivering the aim and objectives, it has indicated areas of further fruitful research. Project aim: to characterise the development of the active naval dockyards at Devonport and Portsmouth, and the facilities within the dockyard boundaries at their maximum extent during the twentieth century, through library, archival and field surveys, presented and analysed in a published report, with a database of documentary and building reports. This has been delivered through Parts 1-4 and Appendices 2-4. Project objectives 1 To provide an overview of the twentieth century development of English naval dockyards, related to historical precedent, national foreign policy and naval strategy. 2 To address the main chronological development phases to accommodate new types of vessels and technologies of the naval dockyards at Devonport and Portsmouth. 3 To identify the major twentieth century naval technological revolutions which affected British naval dockyards. 4 To relate the main chronological phases to topographic development of the yards and changing technological and strategic needs, and identify other significant factors. 5 To distinguish which buildings are typical of the twentieth century naval dockyards and/or of unique interest. -

The British War Office

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1976 The rB itish War Office ;: from the Crimean War to Cardwell, 1855-1868. Paul H. Harpin University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Harpin, Paul H., "The rB itish War Office ;: from the Crimean War to Cardwell, 1855-1868." (1976). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1592. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1592 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BRITISH WAR OFFICE: FROM THE CRIMEAN WAR TO CARDWELL, 1855-1868 A Thesis Presented by Paul H. Harpin Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial Ifillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS May 19 76 History THE BRITISH WAR OFFICE: FROM THE CRIMEAN WAR TO CARDWELL , 1855-1868 A Thesis by Paul H. Harpin Approved as to style and content by: Harold J. Gordon, Jr. , Chairmakyof Committee Franklin B. Wickv/lre, Member Mary B. Wickwire , Member Gerald W. McFarland, Department Head History Department May 1976 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. INEFFICIENCY, NEGLIGENCE AND THE CRIMEAN WAR 7 III. REORGANIZATION 1855-1860 . 27 General 27 Correspondence and the Conduct of Business within the War Office 37 Civil-Military Relations 4 9 Armaments and Artillery Administration .... 53 Engineers 57 Clothing 61 Armaments Manufacture 64 The Accountant General's Office 71 Commissariat * 75 Conclusion 81 IV. -

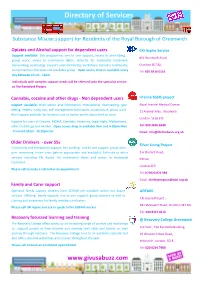

Directory of Services

Directory of Services Substance Misuse support for Residents of the Royal Borough of Greenwich Opiates and Alcohol support for dependent users CRi Aspire Service Support available: Day programme, one to one support, access to prescribing, 821 Woolwich Road, group work, access to community detox, referrals for residential treatment, key working, psychology support, peer mentoring, workshops, recovery community, Charlton SE7 8JL complimentary therapies and pre detox group. Open access drop in available every Tel: 020 8316 0116 day between 10 am - 12pm Individuals with complex support needs will be referred onto the specialist service at The Beresford Project. Cannabis, cocaine and other drugs - Non dependent users Lifeline BaSIS project Support available: Brief advice and information, motivational interviewing, goal Royal Arsenal Medical Centre setting, healthy living tips, self management techniques, acupuncture, group work. 21 Arsenal Way , Woolwich Brief support available for between one to twelve weeks dependent on need. London SE18 6TE Support for users of Cocaine, MDMA, Cannabis, Ketamine, Legal Highs, Methadrone, other Club Drugs and Alcohol. Open access drop in available 9am and 4:30pm Mon Tel: 020 3696 2640 - Fri and 9.30am - 12.30pm Sat Email: [email protected] Older Drinkers - over 55s Silver Lining Project Community and therapeutic support, key working, one to one support, group work, peer mentoring. Home visits (where appropriate and available). Referrals to other 2-6 Sherard Road, services including CRi Aspire -for community detox and access to residential Eltham, treatment. London SE9 Please call to make a referral or an appointment Tel: 079020 876 983 Email: [email protected] Family and Carer support Specialist family support workers from ADFAM are available within our Aspire ADFAM services. -

Naval Dockyards Society

20TH CENTURY NAVAL DOCKYARDS: DEVONPORT AND PORTSMOUTH CHARACTERISATION REPORT Naval Dockyards Society Devonport Dockyard Portsmouth Dockyard Title page picture acknowledgements Top left: Devonport HM Dockyard 1951 (TNA, WORK 69/19), courtesy The National Archives. Top right: J270/09/64. Photograph of Outmuster at Portsmouth Unicorn Gate (23 Oct 1964). Reproduced by permission of Historic England. Bottom left: Devonport NAAFI (TNA, CM 20/80 September 1979), courtesy The National Archives. Bottom right: Portsmouth Round Tower (1843–48, 1868, 3/262) from the north, with the adjoining rich red brick Offices (1979, 3/261). A. Coats 2013. Reproduced with the permission of the MoD. Commissioned by The Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England of 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London, EC1N 2ST, ‘English Heritage’, known after 1 April 2015 as Historic England. Part of the NATIONAL HERITAGE PROTECTION COMMISSIONS PROGRAMME PROJECT NAME: 20th Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth (4A3.203) Project Number 6265 dated 7 December 2012 Fund Name: ARCH Contractor: 9865 Naval Dockyards Society, 44 Lindley Avenue, Southsea, PO4 9NU Jonathan Coad Project adviser Dr Ann Coats Editor, project manager and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Davies Editor and reviewer, project executive and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Evans Devonport researcher David Jenkins Project finance officer Professor Ray Riley Portsmouth researcher Sponsored by the National Museum of the Royal Navy Published by The Naval Dockyards Society 44 Lindley Avenue, Portsmouth, Hampshire, PO4 9NU, England navaldockyards.org First published 2015 Copyright © The Naval Dockyards Society 2015 The Contractor grants to English Heritage a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, perpetual, irrevocable and royalty-free licence to use, copy, reproduce, adapt, modify, enhance, create derivative works and/or commercially exploit the Materials for any purpose required by Historic England. -

Making the Most of London's Waterways

MAKING THE MOST OF LONDON’S WATERWAYS ABOUT FUTURE OF LONDON Future of London helps build better cities through knowledge, networks and leadership – across disciplines, organisations and sectors. We are the capital’s independent network for regeneration, housing, infrastructure and economic development practitioners, with 4,000+ professionals using FoL as a hub for sector intelligence, connection and professional development, and a mandate to prepare the next wave of cross-sector city leaders. PROJECT TEAM Amanda Robinson, Oli Pinch, Nicola Mathers, Aydin Crouch Report written and designed by: Amanda Robinson Report edited by: Charli Bristow, Nicola Mathers, Lisa Taylor PROJECT PARTNERS CORE PARTNERS We are grateful to Arup, Avison Young, Pollard Thomas Edwards and Hadley Property Group for supporting this work. Arup is an independent firm of designers, planners, engineers, consultants and technical specialists offering a broad range of professional services. Avison Young is the world’s fastest growing real estate business. Pollard Thomas Edwards specialises in the creation of new neighbourhoods and the revitalisation of old ones. Their projects embrace the whole spectrum of residential development and other essential ingredients which make our cities, towns and villages into thriving and sustainable places. Hadley Property Group is a developer which specialises in progressive, sustainable approaches to the delivery of much-needed housing in Greater London and other major UK cities. REPORT PARTNER EVENT PARTNER The Canal & River Trust kindly The Port of London Authority kindly provided event and report support. provided event support. Published December 2019 © Future of London 2011 Ltd. Cover photo of Packington Estate kindly supplied by Pollard Thomas Edwards © Tim Crocker. -

Harashim 2010

Harashim The Quarterly Newsletter of the Australian & New Zealand Masonic Research Council ISSN 1328-2735 Issue 49 January 2010 First Prestonian Lecture in Australia John Wade at Discovery Lodge of Research Laurelbank Masonic Centre, in the inner Sydney suburbs, was the venue for the presentation of the first Prestonian Lecture in Australia by a current Prestonian Lecturer. Discovery Lodge of Research held a special meeting there on Wednesday 6 January to receive the Master of Quatuor Coronati Lodge No. 2076 EC, the editor of Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, and the Prestonian Lecturer for 2009—all in the person of Sheffield University’s Dr John Wade. Some 37 brethren attended the lodge, including the Grand Master, MWBro Dr Greg Levenston, and representatives from Newcastle and Canberra. WM Ewart Stronach introduced Bro Wade, outlining his academic and Masonic achievements, gave a brief account of the origin of Prestonian Lectures, and closed the lodge. Ladies and other visitors were then admitted, swelling the audience to 54, for a brilliant rendition of the lecture: ‘“Go and do thou likewise”, English Masonic Processions from the 18th to the 20th Centuries’. Bro Wade made good use of modern technology with a PowerPoint presentation, including early film footage of 20th-century processions, supplementing it with his own imitation of a fire-and-brimstone preacher, and a spirited rendition of the first verse of The Entered Apprentice’s Song. (continued on page 16) From left: GM Dr Greg Levenston, Tom Hall, WM Ewart Stronach, Ian Shanley, Dr John Wade, Malcolm Galloway, Dr Bob James, Tony Pope, Neil Morse, Andy Walker Issue 49 photo from John page Wade 1 About Harashim Harashim, Hebrew for Craftsmen, is a quarterly newsletter published by the Australian and New Zealand Masonic Research Council (10 Rose St, Waipawa 4210, New Zealand) in January, April, July and October each year.