Pathfinding It Took Years for Journalist Jody Porter to See That Writing About Other People’S Pain Can Be a Way of Hiding from Your Own

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legacy Schools Reconciliaction Guide Contents

Legacy Schools ReconciliACTION Guide Contents 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WELCOME TO THE LEGACY SCHOOLS PROGRAM 5 LEGACY SCHOOLS COMMITMENT 6 BACKGROUND 10 RECONCILIACTIONS 12 SECRET PATH WEEK 13 FUNDRAISING 15 MEDIA & SOCIAL MEDIA A Message from the Families Chi miigwetch, thank you, to everyone who has supported the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund. When our families embarked upon this journey, we never imagined the potential for Gord’s telling of Chanie’s story to create a national movement that could further reconciliation and help to build a better Canada. We truly believe it’s so important for all Canadians to understand the true history of Indigenous people in Canada; including the horrific truths of what happened in the residential school system, and the strength and resilience of Indigenous culture and peoples. It’s incredible to reflect upon the beautiful gifts both Chanie & Gord were able to leave us with. On behalf of both the Downie & Wenjack families -- Chi miigwetch, thank you for joining us on this path. We are stronger together. In Unity, MIKE DOWNIE & HARRIET VISITOR Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund 3 Introduction The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) is part of Gord Downie’s legacy and embodies his commitment, and that of his family, to improving the lives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. In collaboration with the Wenjack family, the goal of the Fund is to continue the conversation that began with Chanie Wenjack’s residential school story, and to aid our collective reconciliation journey through a combination of awareness, education and connection. Our Mission Inspired by Chanie’s story and Gord’s call to action to build a better Canada, the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) aims to build cultural understanding and create a path toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. -

Annual Report 2019 / 2020 5

reconciliaction love acknowledgment forgiveness education openness recognition reflection connection love awareness truth respect hope exploration leadership forgiveness communication grace curiosity inspiration education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth reconciliaction caring education humility openness recognition reflection connection recognition reflection curiosity acknowledgment forgiveness love acknowledgment forgiveness love exploration patience communication exploration patience communication ANNUA L caring grace curiosity hope truth REPORT legacy grace curiosity hope truth reconciliaction love humility 2019 - 2020 communication curiosity inspiration grace exploration awareness forgiveness reconciliaction curiosity inspiration grace education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth education respect openness caring Contents Land Acknowledgement ............................................................................................. 3 Message from the Families ......................................................................................... 4 Message from CEO ...................................................................................................... 5 Our Purpose ................................................................................................................ -

'69 Bryan Adams 2 New Orleans Is Sinking the Tragically Hip 3 Life Is

1 Summer of '69 Bryan Adams 2 New Orleans Is Sinking The Tragically Hip 3 Life Is A Highway Tom Cochrane 4 Takin' Care of Business Bachman Turner Overdrive 5 Tom Sawyer Rush 6 Working For The Weekend Loverboy 7 American Woman The Guess Who 8 Bobcaygeon The Tragically Hip 9 Roll On Down the Highway Bachman Turner Overdrive 10 Heart Of Gold Neil Young 11 Rock and Roll Duty Kim Mitchell 12 38 Years Old The Tragically Hip 13 New World Man Rush 14 Wheat Kings The Tragically Hip 15 The Weight The Band 16 These Eyes The Guess Who 17 Everything I Do (I Do IT For You) Bryan Adams 18 Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf 19 Run To You Bryan Adams 20 Tonight is a Wonderful Time to Fall in Love April Wine 21 Turn Me Loose Loverboy 22 Rock You Helix 23 We're Here For A Good Time Trooper 24 Ahead By A Century The Tragically Hip 25 Go For Soda Kim Mitchell 26 Whatcha gonna Do (When I'm Gone) Chilliwack 27 Closer To The Heart Rush 28 Sweet City Woman The Stampeders 29 Chicks ‘N Cars (And the Third World War) Colin James 30 Rockin' In The Free World Neil Young 31 Black Velvet Alannah Myles 32 Heaven Bryan Adams 33 Feel it Again Honeymoon Suite 34 You Could Have Been A Lady April Wine 35 Gimme Good Lovin' Helix 36 The Spirit Of Radio Rush 37 Sundown Gordon Lightfoot 38 This Beat Goes on/ Switchin' To Glide The Kings 39 Sunny Days Lighthouse 40 Courage The Tragically Hip 41 At the Hundreth Meridian The Tragically Hip 42 The Kid Is Hot Tonite Loverboy 43 Life is a Carnival The Band 44 Don't It Make You Feel The Headpins 45 Eyes Of A Stranger Payolas 46 Big League -

You Can't See Me I Am a Stranger…Do You Know What I Mean?

The Stranger I am a stranger…You can't see me I am a stranger…Do you know what I mean? I navigate the mud…I walk above the path Jumpin' to the right…Then I jump to the left On a secret path The one that nobody knows And I'm moving fast On the path nobody knows And what I'm feelin'…Is anyone's guess What is in my head…And what's in my chest I'm not gonna stop…I'm just catching my breath They're not gonna stop…Please just let me catch my breath I am the stranger…You can't see me I am the stranger…Do you know what I mean? That is not my dad…My dad is not a wild man Doesn't even drink…My dad, he's not a wild man On a secret path The one that nobody knows And I'm moving fast On the path that nobody knows I am the stranger… I am the stranger… I am the stranger… I am the stranger… www.downiewenjack.ca Grace, too He said I'm fabulously rich C'mon just let's go She kinda bit her lip Geez, I don't know But I can guarantee There'll be no knock on the door I'm total pro That's what I'm here for I come from downtown Born ready for you Armed with will and determination And grace, too The secret rules of engagement Are hard to endorse When the appearance of conflict Meets the appearance of force But I can guarantee There'll be no knock on the door I'm total pro That's what I'm here for I come from downtown Born ready for you Armed with skill and it's frustration And grace, too www.downiewenjack.ca Poets Spring starts when a heartbeat's pounding When the birds can be heard Above the reckoning carts doing some final accounting Lava flowing in Superfarmer’s -

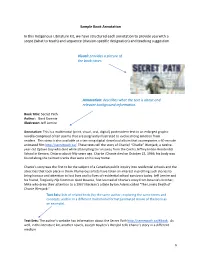

6 Sample Book Annotation in This Indigenous Literature Kit, We Have Structured Each Annotation to Provide You with a Scope

Sample Book Annotation In this Indigenous Literature Kit, we have structured each annotation to provide you with a scope (what to teach) and sequence (division-specific designation) and teaching suggestion. Visual: provides a picture of the book cover. Annotation: describes what the text is about and relevant background information. Book Title: Secret Path Author: Gord Downie Illustrator: Jeff Lemire Annotation: This is a multimodal (print, visual, oral, digital) postmodern text in an enlarged graphic novella comprised of ten poems that are poignantly illustrated to evoke strong emotion from readers. This story is also available as a ten-song digital download album that accompanies a 60-minute animated film http://secretpath.ca/. These texts tell the story of Chanie/ “Charlie” Wenjack, a twelve- year-old Ojibwe boy who died while attempting to run away from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario about fifty years ago. Charlie /Chanie died on October 22, 1966; his body was found along the railroad tracks that were on his way home. Chanie’s story was the first to be the subject of a Canadian public inquiry into residential schools and the atrocities that took place in them. Numerous artists have taken an interest in profiling such stories to bring honour and attention to lost lives and to lives of residential school survivors today. Jeff Lemire and his friend, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, first learned of Chanie's story from Downie's brother, Mike who drew their attention to a 1967 Maclean's article by Ian Adams called "The Lonely Death of Chanie Wenjack." Text Sets: lists of related texts (by the same author; exploring the same terms and concepts; and/or in a different multimodal format (animated movie of the book as an example). -

Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 14.1.14 Halifax Regional Council December 12, 2017 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council SUBMITTED BY: Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: November 30, 2017 SUBJECT: The Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project ORIGIN July 18, 2017 Regional Council Motion: MOVED by Mayor Savage, seconded by Councillor Outhit, that Regional Council request a staff report to: 1. Evaluate the municipality’s potential participation in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project, including through an annual $5,000 contribution for 5 years to the Downie Wenjack Fund; and 2. Evaluate the viability of establishing a Legacy Room within City Hall as a dedicated space for the display of aboriginal art. MOTION PUT AND PASSED UNANIMOUSLY LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Halifax Regional Municipality Charter, S.N.S. 2008, c. 39, section 79 (1) The Council may expend money required by the Municipality for … (av) a grant or contribution to … (vii) a registered Canadian charitable organization; RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that Halifax Regional Council: 1. Approve a one-time contribution in the amount of $25,000 from Account M311- Grants and Tax Concession to the Tides Canada Foundation to support cross-cultural reconciliation projects funded under the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund; …RECOMMENDATION CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 The Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project Council Report - 2 - December 12, 2017 2. Establish a Downie Wenjack Legacy Room in the Main Floor Boardroom at City Hall as per the terms of the Downie Wenjack Fund; 3. Authorize the Chief Administrative Officer to negotiate and execute an agreement to participate in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project with the Tides Canada Initiatives Society; 4. -

Enviro-News October, 2013

Enviro-News October, 2013 Sponsored by Daemen College’s Center for Sustainable Communities and Civic Engagement and Global & Local Sustainability Program Newsletter Contents: Articles- including events, courses, local news, grants, positions Upcoming Activities Tips to Help the Environment Articles: Buffalo: America's Best Designed City Film Premiere Western New Yorkers are invited to the free public premiere of a brand new short documentary that tells the story of Buffalo and its world class design. The premiere will be at 7pm on Tuesday, October 1 at Larkin Square, 745 Seneca Street. To read more about the film, visit www.bestdesignedcity.com. The unveiling will coincide with the popular Food Truck Tuesday night in Larkin Square. 2013 Conference on the Environment: A Bi-National Summit The Conference on the Environment will take place at the Adam's Mark Hotel from October 3-5, 2013. Join environmental professionals and community leaders from the U.S. and Canada for learning and networking opportunities. Registration is $120 and includes all sessions, select meals and a ticket to a Gord Downie concert on October 3. Visit coe2013.org for info or contact Peter Rizzo at [email protected]. An Evening with Gord Downie to Benefit Buffalo Niagara Riverkeeper Gord Downie—front man for the band, The Tragically Hip—will perform an evening of song and conversation on the environment on October 3rd at the Adam’s Mark Hotel as kickoff for the Conference on the environment. Concert tickets are available to the public for $25 at http://coe2013.brownpapertickets.com/ . Doors open at 6pm with performance at 7:30pm. -

Camera Stylo 2019 Inside Final 9

Moving Forward as a Nation: Chanie Wenjack and Canadian Assimilation of Indigenous Stories ANDALAH ALI Andalah Ali is a fourth year cinema studies and English student. Her primary research interests include mediated representations of death and alterity, horror, flm noir, and psychoanalytic theory. 66 The story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibwe boy who froze to death in 1966 while fleeing from Cecilia Jeffery Indian Residential School,1 has taken hold within Canadian arts and culture. In 2016, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the young boy’s tragic and lonely death, a group of Canadian artists, including Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, comic book artist Jeff Lemire, and filmmaker Terril Calder, created pieces inspired by the story.2 Giller Prize-winning author Joseph Boyden, too, participated in the commemoration, publishing a novella, Wenjack,3 only a few months before the literary controversy wherein his claims to Indigenous heritage were questioned, and, by many people’s estimation, disproven.4 Earlier the same year, Historica Canada released a Heritage Minute on Wenjack, also written by Boyden.5 Ostensibly, the foregrounding of such a story within a cultural institution as mainstream as the Heritage Minutes functions as a means to critically address Canadian complicity in settler-colonialism. By constituting residential schools as a sealed-off element of history, however, the Heritage Minute instead negates ongoing Canadian culpability in the settler-colonial project. Furthermore, the video’s treatment of landscape mirrors that of the garrison mentality, which is itself a colonial construct. The video deflects from discourses on Indigenous sovereignty or land rights, instead furthering an assimilationist agenda that proposes absorption of Indigenous stories, and people, into the Canadian project of nation-building. -

Residential Schools in Canada: an Education Guide

RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map of residential schools in Canada (courtesy of National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, University of Manitoba). Thomas Moore, Regina Indian Industrial School, c. 1874 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/NL-022474). “ When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that the Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.” — Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, Official report of the debates of the Table of Contents House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada, 9 May 1883, 1107–1108 Introduction: Residential Schools 2 Introduction: residential schools Message to Teachers 3 Residential schools were government-sponsored religious schools established to assimilate The Legacy of Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian society. Successive Canadian governments used Indian Residential Schools 4 legislation to strip Indigenous peoples of basic human and legal rights, dignity and integrity, Timeline 5 and to gain control over the peoples, their lands and natural rights and resources. The Indian Act, Historical Significance: first introduced in 1876, gave the Canadian government license to control almost every aspect Timeline Activity 8 of Indigenous peoples’ lives. -

Tragically Hip Long Time Running Movie Torrent Download Long Time Running | Listen to the Tragically Hip Long Time Running MP3 Song

tragically hip long time running movie torrent download Long Time Running | Listen to The Tragically Hip Long Time Running MP3 song. Long Time Running song from the album Yer Favourites is released on Nov 2005 . The duration of song is 04:23. This song is sung by The Tragically Hip. Related Tags - Long Time Running, Long Time Running Song, Long Time Running MP3 Song, Long Time Running MP3, Download Long Time Running Song, The Tragically Hip Long Time Running Song, Yer Favourites Long Time Running Song, Long Time Running Song By The Tragically Hip, Long Time Running Song Download, Download Long Time Running MP3 Song. The Tragically Hip's documentary gets an emotional trailer (VIDEO) The Tragically Hip had an epic and emotional year in 2016. The iconic Canadian band’s legendary last tour captured the hearts of the country, and now, the moments can be relived on the big screen. The Hip’s new documentary Long Time Running is an intimate look at the band’s last tour, from behind-the-scenes and on-stage footage, to personal interviews with the band, fans are in for a treat with this one. The film, directed by Jennifer Baichwal and Nick de Pencier, will have its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, then will be released theatrically in select Cineplex and Landmark movie theatres across Canada starting September 14. The Tragically Hip. The Tragically Hip, often referred to simply as The Hip, were a Canadian rock band from Kingston, Ontario, consisting of lead front man Gord Downie, guitarist Paul Langlois, guitarist Rob Baker (known as Bobby Baker until 1994), bassist Gord Sinclair, and drummer Johnny Fay. -

Tragically!Hip's!

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Man!Machine!Poem:!Viewing!the!Tragically!Hip’s!final!tour!through!a!post;humanitarianism! lens! ! Connor!Vreugdenhil;Beauclerc,!6477662! ! Submitted:!April!25th,!2018! ! Department!of!Communications,!Faculty!of!Arts,!University!of!Ottawa! Master!of!Arts!Communication! ! ©!Connor!Vreugdenhil;Beauclerc,!Ottawa,!Canada,!2018! ! ! ! ! Abstract!! In!late!2015,!Gord!Downie,!lead!singer!of!the!iconic!Canadian!rock!band!the!Tragically!Hip!was! diagnosed!with!glioblastoma,!a!terminal!brain!cancer.!Some!eight!months!later,!on!August!20,! 2016,!the!band!completed!its!final!concert!tour!in!its!home!town!of!Kingston,!Ontario.!One!of!the! many!noteworthy!features!of!the!tour!was!the!extensive!fan;based!fundraising!efforts!for!brain! cancer!research!that!accompanied!it.!In!recent!years!some!commentators!have!characterized!this! type! of! emotional! outpouring! as! a! form! of! ethical! ambivalence! or! post;humanitarianism! reflecting! a! sensibility! of! pity! that! valorizes! a! consumerist! oriented! form! of! short;term! low; intensity! agency! as! opposed! to! some! more! authentic! forms! of! empathy.! A! leading! figure! in! developing!the!concept!of!post;humanitarianism!is!Lilie!Chouliaraki.!Her!2013!book,!The!Ironic! Spectator,!investigates!four!different!aspects!of!contemporary!humanitarian!communication!–! appeals,!celebrity,!concerts,!and!news!–!to!examine!the!ethical!ambivalence!underlying!post; humanitarianism.! Drawing! on! Chouliaraki’s! claims! about! the! influence! of! celebrity! and! news! reporting! in! fostering! -

École Polytechnique

Music and Arts in Action | Volume 4 | Issue 1 Choral, Public and Private Listener Responses to Hildegard Westerkamp's École Polytechnique ANDRA MCCARTNEY & MARTA MCCARTHY Department of Communication Studies| Concordia University | Canada Department of Music | University of Guelph | Canada* ABSTRACT Hildegard Westerkamp's (1990) composition École Polytechnique is an artistic response to one of Canada's most profoundly disturbing mass murders, the 1989 slaying of fourteen women in Montreal, Quebec. Using the theoretical model, derived from Haraway, of the cyborg body, and analyzing the import of the mixed media (voices, instruments and electroacoustic tape) incorporated in the music, the authors examine the impact this work has had on some of those who have heard it and performed it, based on the responses of choristers and listeners in several studies. The authors explored how those who engaged significantly with the music, (including those who had no personal association with the actual events of the 1989 massacre), were able to make relevant connections between their own experience and the composition itself, embrace these connections and their disturbing resonances, and thereby experience meaningful emotional growth. *School of Fine Art & Music, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada N1G 2W1 © Music and Arts in Action/McCartney & McCarthy 2012 | ISSN: 1754-7105 | Page 56 http://musicandartsinaction.net/index.php/maia/article/view/chorallistening Music and Arts in Action | Volume 4 | Issue 1 INTRODUCTION On December 6, 1989 fourteen women were shot to death at École Polytechnique, University of Montréal. The killer then turned the gun on himself. This massacre brought public attention to the issue of violence against women within Canadian society.