École Polytechnique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legacy Schools Reconciliaction Guide Contents

Legacy Schools ReconciliACTION Guide Contents 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WELCOME TO THE LEGACY SCHOOLS PROGRAM 5 LEGACY SCHOOLS COMMITMENT 6 BACKGROUND 10 RECONCILIACTIONS 12 SECRET PATH WEEK 13 FUNDRAISING 15 MEDIA & SOCIAL MEDIA A Message from the Families Chi miigwetch, thank you, to everyone who has supported the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund. When our families embarked upon this journey, we never imagined the potential for Gord’s telling of Chanie’s story to create a national movement that could further reconciliation and help to build a better Canada. We truly believe it’s so important for all Canadians to understand the true history of Indigenous people in Canada; including the horrific truths of what happened in the residential school system, and the strength and resilience of Indigenous culture and peoples. It’s incredible to reflect upon the beautiful gifts both Chanie & Gord were able to leave us with. On behalf of both the Downie & Wenjack families -- Chi miigwetch, thank you for joining us on this path. We are stronger together. In Unity, MIKE DOWNIE & HARRIET VISITOR Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund 3 Introduction The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) is part of Gord Downie’s legacy and embodies his commitment, and that of his family, to improving the lives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. In collaboration with the Wenjack family, the goal of the Fund is to continue the conversation that began with Chanie Wenjack’s residential school story, and to aid our collective reconciliation journey through a combination of awareness, education and connection. Our Mission Inspired by Chanie’s story and Gord’s call to action to build a better Canada, the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) aims to build cultural understanding and create a path toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. -

WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association

ACLA 2017 ACLA WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome and Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................4 Welcome from Utrecht Mayor’s Office .....................................................................................6 General Information ................................................................................................................... 7 Conference Schedule ................................................................................................................. 14 Biographies of Keynote Speakers ............................................................................................ 18 Film Screening, Video Installation and VR Poetry ............................................................... 19 Pre-Conference Workshops ...................................................................................................... 21 Stream Listings ..........................................................................................................................26 Seminars in Detail (Stream A, B, C, and Split Stream) ........................................................42 Index......................................................................................................................................... 228 CFP ACLA 2018 Announcement ...........................................................................................253 Maps -

'69 Bryan Adams 2 New Orleans Is Sinking the Tragically Hip 3 Life Is

1 Summer of '69 Bryan Adams 2 New Orleans Is Sinking The Tragically Hip 3 Life Is A Highway Tom Cochrane 4 Takin' Care of Business Bachman Turner Overdrive 5 Tom Sawyer Rush 6 Working For The Weekend Loverboy 7 American Woman The Guess Who 8 Bobcaygeon The Tragically Hip 9 Roll On Down the Highway Bachman Turner Overdrive 10 Heart Of Gold Neil Young 11 Rock and Roll Duty Kim Mitchell 12 38 Years Old The Tragically Hip 13 New World Man Rush 14 Wheat Kings The Tragically Hip 15 The Weight The Band 16 These Eyes The Guess Who 17 Everything I Do (I Do IT For You) Bryan Adams 18 Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf 19 Run To You Bryan Adams 20 Tonight is a Wonderful Time to Fall in Love April Wine 21 Turn Me Loose Loverboy 22 Rock You Helix 23 We're Here For A Good Time Trooper 24 Ahead By A Century The Tragically Hip 25 Go For Soda Kim Mitchell 26 Whatcha gonna Do (When I'm Gone) Chilliwack 27 Closer To The Heart Rush 28 Sweet City Woman The Stampeders 29 Chicks ‘N Cars (And the Third World War) Colin James 30 Rockin' In The Free World Neil Young 31 Black Velvet Alannah Myles 32 Heaven Bryan Adams 33 Feel it Again Honeymoon Suite 34 You Could Have Been A Lady April Wine 35 Gimme Good Lovin' Helix 36 The Spirit Of Radio Rush 37 Sundown Gordon Lightfoot 38 This Beat Goes on/ Switchin' To Glide The Kings 39 Sunny Days Lighthouse 40 Courage The Tragically Hip 41 At the Hundreth Meridian The Tragically Hip 42 The Kid Is Hot Tonite Loverboy 43 Life is a Carnival The Band 44 Don't It Make You Feel The Headpins 45 Eyes Of A Stranger Payolas 46 Big League -

Tragically Hip Long Time Running Movie Torrent Download Long Time Running | Listen to the Tragically Hip Long Time Running MP3 Song

tragically hip long time running movie torrent download Long Time Running | Listen to The Tragically Hip Long Time Running MP3 song. Long Time Running song from the album Yer Favourites is released on Nov 2005 . The duration of song is 04:23. This song is sung by The Tragically Hip. Related Tags - Long Time Running, Long Time Running Song, Long Time Running MP3 Song, Long Time Running MP3, Download Long Time Running Song, The Tragically Hip Long Time Running Song, Yer Favourites Long Time Running Song, Long Time Running Song By The Tragically Hip, Long Time Running Song Download, Download Long Time Running MP3 Song. The Tragically Hip's documentary gets an emotional trailer (VIDEO) The Tragically Hip had an epic and emotional year in 2016. The iconic Canadian band’s legendary last tour captured the hearts of the country, and now, the moments can be relived on the big screen. The Hip’s new documentary Long Time Running is an intimate look at the band’s last tour, from behind-the-scenes and on-stage footage, to personal interviews with the band, fans are in for a treat with this one. The film, directed by Jennifer Baichwal and Nick de Pencier, will have its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, then will be released theatrically in select Cineplex and Landmark movie theatres across Canada starting September 14. The Tragically Hip. The Tragically Hip, often referred to simply as The Hip, were a Canadian rock band from Kingston, Ontario, consisting of lead front man Gord Downie, guitarist Paul Langlois, guitarist Rob Baker (known as Bobby Baker until 1994), bassist Gord Sinclair, and drummer Johnny Fay. -

Tragically!Hip's!

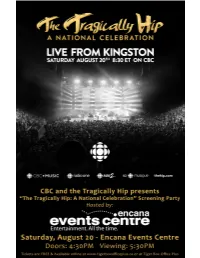

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Man!Machine!Poem:!Viewing!the!Tragically!Hip’s!final!tour!through!a!post;humanitarianism! lens! ! Connor!Vreugdenhil;Beauclerc,!6477662! ! Submitted:!April!25th,!2018! ! Department!of!Communications,!Faculty!of!Arts,!University!of!Ottawa! Master!of!Arts!Communication! ! ©!Connor!Vreugdenhil;Beauclerc,!Ottawa,!Canada,!2018! ! ! ! ! Abstract!! In!late!2015,!Gord!Downie,!lead!singer!of!the!iconic!Canadian!rock!band!the!Tragically!Hip!was! diagnosed!with!glioblastoma,!a!terminal!brain!cancer.!Some!eight!months!later,!on!August!20,! 2016,!the!band!completed!its!final!concert!tour!in!its!home!town!of!Kingston,!Ontario.!One!of!the! many!noteworthy!features!of!the!tour!was!the!extensive!fan;based!fundraising!efforts!for!brain! cancer!research!that!accompanied!it.!In!recent!years!some!commentators!have!characterized!this! type! of! emotional! outpouring! as! a! form! of! ethical! ambivalence! or! post;humanitarianism! reflecting! a! sensibility! of! pity! that! valorizes! a! consumerist! oriented! form! of! short;term! low; intensity! agency! as! opposed! to! some! more! authentic! forms! of! empathy.! A! leading! figure! in! developing!the!concept!of!post;humanitarianism!is!Lilie!Chouliaraki.!Her!2013!book,!The!Ironic! Spectator,!investigates!four!different!aspects!of!contemporary!humanitarian!communication!–! appeals,!celebrity,!concerts,!and!news!–!to!examine!the!ethical!ambivalence!underlying!post; humanitarianism.! Drawing! on! Chouliaraki’s! claims! about! the! influence! of! celebrity! and! news! reporting! in! fostering! -

Gord Downie: Ahead by a Century

Gord Downie: Ahead by a Century Gord Downie, musician, singer, songwriter, environmentalist and native rights activist, left his mark on generations of Canadians. His lyrics for The Tragically Hip, quirky and clever as they are, have become a part of the Canadian soundtrack. Songs such as Blow at High Dough , Courage , Wheat Kings and Bobcaygeon , are now sung at campfires and hockey games, but also analyzed for PhD papers. Their songs explored Canadian geography and history, the themes of the water and the land, creating a sense of pride of place, but also referenced Canadian authors (Hugh MacLennan, for one) and the work of William Shakespeare. Taking pride in their Canadian roots (at a time when it was not cool in music), touring the nation relentlessly in the early days, and consistently evolving, over 13 studio albums and through four decades, the Hip maintained a distinct sound and a strong position in the hearts of English Canada. In the wake of an untreatable brain cancer diagnosis in 2016, Downey chose to go on the road with the Hip, to engage with fans, to conduct a national celebration. Fans raised money for cancer charities. The Tragically Hip’s final concert, held in their hometown of Kingston, ON, on August 20, 2016, was broadcast nationally and viewed in parks across Canada, hitting record viewer numbers of over 11 million. Downie chose to use his final days to highlight causes close to his heart. Secret Path: The Story of Chanie Wenjack , highlighted the legacy of the residential school system and its impact on First Nations. -

Gord Downie 1964-2017

Levels 1 & 2 (grades 5 and up) Gord Downie 1964-2017 Article page 2 Questions page 4 Photo page 6 Crossword page 7 Quiz page 8 Breaking news november 2017 A monthly current events resource for Canadian classrooms Routing Slip: (please circulate) National Farewell, Gord Downie – And thank you for the music Th e country was united in sorrow on “If you’re a musician and you’re born “I thought I was going to make it October 17 when singer-songwriter in Canada it’s in your DNA to like through this but I’m not,” the prime Gord Downie died of terminal brain the Tragically Hip,” said Canadian minister said. His voice broke and cancer. He was 53. Mr. Downie was musician Dallas Green. he cried openly. “We all knew it was the front man of Th e Tragically Hip, coming,” Mr. Trudeau said. “But His last great concerts arguably the nation’s most beloved we hoped it wasn’t. We are less as a rock band. Th e band played a series of concerts country without Gordon Downie.” across Canada last summer. Th e CBC “Gord knew this day was coming,” Another fan, Melanie Wells, paid her carried the last show in Kingston. Th e his family wrote on his website. “His respects to Mr. Downie at a day-long broadcast aired in pubs, parks, and response was to spend this precious memorial held in Kingston. “It’s a drive-in movie theatres across the time as he always had – making music, band that’s been with me my whole country. -

Long Time Running Arranged for Piano

From the album "Road Apples" by The Tragically Hip Long Time Running Arranged for Piano Written By GORD DOWNIE, Folk Rock Ballad (q. = 54) ROB BAKER, et. al A E/G© F©‹ E Dƒ‡‡Ù E # # 6 & # 8 Œ j j j j ‰ j ‰ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ mf œ œ œ œ™ œ œ™ ?# # 6 j œ j œ # 8 œ œ j œ j œ j j œ œ œ™ œ œ œ™ œ œ Verse 1 { A F©‹ ### r r œ r œ r r j & Œ™ Œ œ œ R œ™ œ œ œ™ Œ™ œ œ œ™ ‰ œ œ œ Does your mo-thJer teRll you things? Long, long when I'm gone? # ## Œ & j j j j œ œ™ œ™ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ™ œ œ œœ™ œœ œ >. ™ ™ >. ™ ?### j ‰ ‰ j j ‰ j œ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ™ œ œ œ œ™ { A F©‹ ### œ j r j œ r r & ∑ R œ œ œ œ œ™ Œ™ Œ œ R œ œ ‰ œ™ œ Who aRre you taRlk-ing to? 'She tell-ing you I'Jm the # # & # ‰ ‰ j œ j œ œ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ™ >. œ œ™ œ œ œ ?### ‰ j ˙™ ˙ œ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ™ { © 1991 MCA/Sire Records Long Time Running -2- E Dƒ‡‡Ù ### r r r r r r & œœœ Œ™ Œ™ Œ œ œ œ œ œ œ™ Œ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ one? It's a grRave mis- take and I'm wRide a- wake # # & # j j œ œ œ œ œ œœ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ™œ œ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ J œ™ ?### j j œ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ œ œ™ J J J Verse 2 { A E/G© F©‹ E Dƒ‡‡Ù E A # ## ∑ ∑ ∑ Œ ‰ œ œ & ˙™ ™ J Drive-inJ's # ## j >. -

Hugh Padgham Discography

JDManagement.com 914.777.7677 Hugh Padgham - Discography updated 09.01.13 P=Produce / E=Engineer / M=Mix / RM=Remix GRAMMYS (4) MOVIE STUDIO / RECORD LABEL ARTIST / COMPOSER / PROGRAM FILM SCORE / ALBUM / TV SHOW CREDIT / NETWORK Sting Ten Summoner's Tales E/M/P A&M Best Engineered Album Phil Collins "Another Day In Paradise" E/M/P Atlantic Record Of The Year Phil Collins No Jacket Required E/M/P Atlantic Album Of The Year Hugh Padgham and Phil Collins No Jacket Required E/M/P Atlantic Producer Of The Year ARTIST ALBUM CREDIT LABEL 2013 Hall and Oates Threads and Grooves M RCA 2012 Adam Ant Playlist: The Very Best of Adam Ant P Epic/Legacy Dominic Miller 5th House M Ais / Q-Rious Music Clannad The Essential Clannad P RCA McFly Memory Lane: The Best of McFly M/P Island 2011 Sting The Best of 25 Years P/E/M Polydor/A&M Records Melissa Etheridge Icon P Island Van der Graaf Generator A Grounding in Numbers M Esoteric Records Various Artists Grandmaster II Project P/E/M Extreme 2010 The Bee Gees Ultimate Bee Gees: The 50th Anniversary Collections P/E/M Rhino Youssou N'Dour/Peter Gabriel Shakin' The Tree M Virgin Van der Graff Generator A Grounding In Numbers M Virgin Tina Turner Platinum Collection P/E/M Virgin Hall & Oates Collection: H2O, Private Eyes, Voices M RCA Tim Finn Anthology: North South East West P/E/M EMI Music Dist. Mummy Calls Mummy Calls P/E/M Geffen 311 Playlist: The Very Best of 311 P Legacy Various Artists Ashes to Ashes, Series 2 P/E/M Sony Various Artists Rock For Amnesty P/E/M Mercury 2009 Tina Turner The Platinum Collection P Virgin Hall & Oates The Collection: H20/Private Eyes/Voices M RCA Bee Gees The Ultimate Bee Gees: The 50th Anniversary Collection P Rhino Dominic Miller In A Dream P/E/M Independent Lo-Star Closer To The Sun P/E/M Independent Danielle Harmer Superheroes P/E/M EMI Original Soundtrack Ashes to Ashes, Series 2 P Sony Music Various Artists Grandmaster Project P/E/M Extreme Various Artists Now, Vol. -

Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project 2018-2019

North Vancouver School District Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project 2018-2019 The North Vancouver School District is very honoured to have five schools selected to be part of the Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project. The five schools are École Windsor Secondary, Norgate-Xwemélch’stn, Ns7e’yxnitm la Tel:’wet Westview, Carisbrooke and École Sherwood Park. The Secret Path is an album that began as 10 poems written by Gord Downie from the Tragically Hip, after learning about the death of Chanie Wenjack, who died on October 22, 1966, while trying to get home after fleeing from Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School. The poems later became the basis of an album which was illustrated by Jeff Lemire. You can find out more about the Secret Path here The Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project is a program that provides “opportunity for classrooms/schools to lead the movement in awareness of the history and impact of the Residential School System on Indigenous Peoples” (downiewenjack.ca). Schools/classes participating in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Project are encouraged to create a ReconcilliACTIONs which is representative of their school and community. You can learn more about the Downie Wenjack Legacy Project here . Chanie Wenjack 1 The Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project began with a guest presentation by Mike Downie on behalf of the Downie Wenjack organization, at Norgate-Xwemélch’stn, on October 4, 2018. NVSD representatives from all five Legacy schools were in attendance. Participating schools received a Legacy Schools Toolkit and educational support andresources to share with staff and students. -

April 8-11, 2021

2021 APRIL 8-11, 2021 Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2021 | Virtual Meeting TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome to ACLA 2021 and Acknowledgments. ..................................................................................4 ACLA Board Members ..............................................................................................................................6 Conference Schedule in Brief ...................................................................................................................7 General Information ..................................................................................................................................9 Full Descriptions of Special Events and Sessions .................................................................................10 ACLA Code of Conduct ..........................................................................................................................18 Seminars in Detail: Stream A, 8:30 AM - 10:15 AM .......................................................................................................20 Stream B, 10:30 AM - 12:15 PM ......................................................................................................90 Stream C, 2:00 PM - 3:45 PM .........................................................................................................162 Stream D, 4:00 - 5:45 PM ................................................................................................................190 Split Stream -

Media Package.Indd

Mark Rogers, City of Dawson Creek Councillor Thank you for joining us here today at the Encana Events Centre. On May 24, The Tragically Hip an- nounced that lead singer Gord Downie was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. Even with this news, they would once again travel across Canada to bring the Man Machine Poem Tour to major cities which will end on August 20, 2016 in their hometown of Kingston Ontario. The Tragically Hip are no strangers to Dawson Creek as they came through the City and played here at the Encana Events Centre on July 12, 2011. This weekend will bring a Canadian legacy to an end as The Tragically Hip will play their final show on the Man Machine Poem Tour in Kingston, Ontario on Saturday and here at the Encana Events Centre in partnership with CBC and The Tragically Hip, that final show will be broadcast live here for the fans to see for free. To mark this occasion, the City of Dawson Creek would like to announce: WHEREAS, On May 25, 2016 The Tragically Hip announced that they would tour across Canada this summer, one last time as a band, with Dawson Creek hosting “The Tragically Hip A National Celebra- tion”: Screening Party ; of the Kingston, Ontario stop of the Man Machine Poem Tour AND WHEREAS, the Tragically Hip is known as the quintessential Canadian Rock Band, representing Canada as much as maple syrup and hockey; AND WHEREAS, The Tragically Hip have made a strong cultural and economic impact in Dawson Creek performing at the Encana Events Centre on July 12, 2011 with guests the Trews; AND WHEREAS, The City of Dawson Creek would like to officially thank “The Hip” for the years of music and memories we cherish as proud Canadians; NOW THEREFORE, I do hereby proclaim August 20, 2016 as “THE TRAGICALLY HIP DAY” in Dawson Creek Ryan MacIvor, General Manager, Encana Events Centre With the Encana Events Centre in its 8th year of operations, we have had the pleasure of hosting some of the world’s top acts and legends of Canadian Music.