A Bedlam of Shenanigans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

AN ANALYSIS of the MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS of NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 a THESIS S

AN ANALYSIS OF THE MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Dale Ganz Copyright JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH 2010 Abstract Nina Simone was a prominent jazz musician of the late 1950s and 60s. Beyond her fame as a jazz musician, Nina Simone reached even greater status as a civil rights activist. Her music spoke to the hearts of hundreds of thousands in the black community who were struggling to rise above their status as a second-class citizen. Simone’s powerful anthems were a reminder that change was going to come. Nina Simone’s musical interpretation and approach was very unique because of her background as a classical pianist. Nina’s untrained vocal chops were a perfect blend of rough growl and smooth straight-tone, which provided an unquestionable feeling of heartache to the songs in her repertoire. Simone also had a knack for word painting, and the emotional climax in her songs is absolutely stunning. Nina Simone did not have a typical jazz style. Critics often described her as a “jazz-and-something-else-singer.” She moved effortlessly through genres, including gospel, blues, jazz, folk, classical, and even European classical. Probably her biggest mark, however, was on the genre of protest songs. Simone was one of the most outspoken and influential musicians throughout the civil rights movement. Her music spoke to the hundreds of thousands of African American men and women fighting for their rights during the 1960s. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

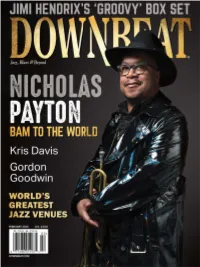

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Council File No. /;;2 ~ /3!:J.~ Council District No

COUNCIL FILE NO. /;;2 ~ /3!:J.~ COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 13 APPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCIL The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1075-S1) without being referred to the Public Works Committee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: _} A. Future Street Acceptance. _} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). _ } C. Dedication of Easement(s). _} D. Release of Restriction(s). __K_} E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. _} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. _} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. _} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAL/DISAPPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* Council Office of the District Public Works Committee Chairperson *DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date ____ notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date ____ scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: ____} Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. ____} Other: PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCIL FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council AUG 2 8 lfJtZ Of the City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C. -

Vince Gill Biography

VINCE GILL BIOGRAPHY “Vince Gill is quite simply a living prism refracting all that is good in country music. He uses the crystal planes of his songwriting, his playing, and his singing to give us a musical rainbow that embraces all men and spans all seasons.” - Kyle Young/Country Music Foundation on Vince’s induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame Vincent Grant Gill was born April 12, 1957 in Norman, Okla. His father encouraged him to learn to play guitar and banjo, which he did along with bass, mandolin, dobro and fiddle. While in high school, he performed in the bluegrass band Mountain Smoke, which built a strong local following and opened a concert for Pure Prairie League. After graduating high school in 1975, Gill moved to Louisville, Ky. to be part of the band Bluegrass Alliance. After a brief time in Ricky Skaggs’s Boone Creek band, Gill moved to Los Angeles and joined Sundance, a bluegrass group fronted by fiddler Byron Berline. In 1979, he joined Pure Prairie League as lead singer and recorded three albums with the band, the first of which yielded the Top Ten pop hit “Let Me Love You Tonight” in 1980. Departing the group in 1981, Gill joined Rodney Crowell’s backing band the Cherry Bombs, where he met and worked with Tony Brown and Emory Gordy Jr., both of whom would later produce many of his future solo albums. In 1983, Gill signed with RCA Records and moved with his wife Janis and daughter Jenny to Nashville to pursue his dream of being a Country Music artist. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Volume Xviii . Number 2 • Summer 1977 • $1.50 Northwest

VOLUME XVIII . NUMBER 2 • SUMMER 1977 • $1.50 NORTHWEST POETRY + NORTHWEST VOLUME EIGHTEEN NUMBER TWO EDITOR SUMMER 1977 David Wagoner JACK CRAWFORD, JR. Four Poems. EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS ROBLEY WILSON, JR. Nelson Bentley, William H. Matchett T wo Poems. GAR BETHEL Four Poems. COVER DESIGN JOHN S. FLAGG Allen Auvil Plot To Restore Reason to the Chair 15 STEPHEN DUNN Three Poems. , Coverfrom a lithograph by Frank Charlie, JOHN ALLMAN Two Poems. a Nootka-Clayoquot artist and carver 19 from Vancouver Island, SEAN BENTLEY titled "Split-Wolf and Split-Moon" American Dream. SANDRA M. GILBERT T hree Poems. BRENDAN GALVIN Running.. ... .. .. BOARD OF ADVISERS GARY GILDNER Toads in the Greenhouse. Leonie Adams, Robert Fitzgerald, Robert B. Heilman, STEPHEN DUNNING Stanley Kunitz,Jackson Mathews, Arnold Stein Dreams of Ducks 30 PHILIP FINE Birds of Winter. POETRY NORTHWEST S U MMER 1977 VOL UME XVIII, NUMBER 2 MARY OLIVER Two Poems. 33 Published quarterly by the University of Washington. Subscriptions and manu JOSEPH DUEMER scripts should be sent to Poetry Northwest, 4045 Brooklyn Avenue NE, Univer Falling. 35 sity of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98105. Not responsible for unsolicited LAURA GROVER manuscripts; all submissions must be accompanied by a stamped self-addressed Calls from a Booth in Time's Square envelope. Subscription rates: U.S., $5.00 per year, single copies $1.50; Canada, $6.00 per year, single copies $1.75. CHARLES BAXTER Deprivation 38 © 1977 by the University of Washington STUART DYBEK Dead Trees. Distributed by B. DeBoer, 188 High Street, Nutley, N.J. 07110; and in the West by L-S Distributors, 1161 Post Street, San Francisco, Calif. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Pansy Division

Pansy Division Pansy Division in 2003. by Linda Rapp Promotional photograph by Richard Turtletaub. Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com San Francisco-based Pansy Division, now consisting of Christopher Freeman (b. 1961), Jon Ginoli (b. 1959), Patrick Goodwin (b. 1973), and Luis Illades (b. 1974), was the first rock band entirely composed of gay musicians who sang frankly gay-themed tunes. After a productive period of recording and touring they had a fallow spell but have recently re-emerged with a new album and a more mature sound. Guitarist Jon Ginoli and bassist Chris Freeman started the band in 1991. They were accompanied by a drummer, but for the first five years the percussionists came and went with regularity. Ginoli and Freeman felt doubly marginalized: the rock world was not particularly welcoming to gays, and many in the gay community were less than enthusiastic about punk rock music. They rose to the challenge by writing music that was unabashedly gay and punk and that also showed a sense of humor. Pansy Division's first album, Undressed, which featured titles such as "Fem in a Black Leather Jacket" and "Boyfriend Wanted," appeared in 1993. Thereafter, they put out an album a year until 1998. The debut album caught the attention of another Bay Area band, Green Day, who signed them as the opening act for their concerts. The Green Day band members were not gay, but they strongly supported Pansy Division and brought them along on tour for five years. Concert audiences were sometimes hostile to the gay band, however. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

Christmas O Christmas Tree Christmas O Come All Ye Faithful

Christmas O Christmas Tree Christmas O come All Ye Faithful Christmas O Come O Come Emmanuel Celine Dion O Holy Night Christmas O Holy Night Tevin Campbell O Holy Night Christmas O Little Town of Bethlehem Christmas O Tannenbaum Shakira Objection Beatles Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da Animotion Obsession Frankie J. & Baby Bash Obsession (No Es Amor) [Karaoke] Christina Obvious Yellowcard Ocean Avenue Billie Eilish Ocean Eyes Billie Eilish Ocean Eyes George Strait Ocean Front Property Bobbie Gentry Ode To Billy Joe Adam Sandler Ode To My Car Cranberries Ode To My Family Alabama Of Course I'm Alright Michael Jackson Off The Wall Lana Del Rey Off To The Races Dave Matthews Oh Buddy Holly Oh Boy Neil Sedaka Oh Carol Shaggy Oh Carolina Beatles Oh Darling Madonna Oh Father Paul Young Oh Girl Sister Act Oh Happy Day Larry Gatlin Oh Holy Night Vanessa Williams Oh How The Years Go By Ulf Lundell oh la la Don Gibson Oh Lonesome Me Brad Paisley & Carrie Underwood Oh Love (Duet) Diamond Rio Oh Me Oh My Sweet Baby Stampeders Oh My Lady Roy Orbison Oh Pretty Woman Ready For the world Oh Sheila Steve Perry Oh Sherrie Childrens Oh Susanna Blessed Union of Souls Oh Virginia Frankie Valli Oh What A Night (December '63) Big Tymers & Gotti & Boo & Tateeze Oh Yeah! [Karaoke] Wiseguys Ohh la la Linda Ronstadt Ohhh Baby Baby Crosby Stills Nash and Young Ohio Merle Haggard Okie From Muskogee Billy Gilman Oklahoma [Karaoke] Reba McEntire and Vince gill Oklahoma Swing Eagles Ol 55 Randy Travis Old 8X10 Brad Paisley Old Alabama Kenny Chesney Old Blue Chair Jim Reeves Old Christmas Card Nickelback Old Enough Three Dog Night Old Fashioned Love Song Alabama Old Flame Dolly Parton Old Flames Can't Hold A Candle To You Mark Chesnutt Old Flames Have New Names Phil Stacey Old Glory Eric Clapton Old Love Childrens Old MacDonald Hootie and the Blowfish Old Man & Me Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Tanya Tucker Old Weakness George Micheal Older Cherie Older Than My Years Trisha Yearwood On A Bus To St.