The Institutional Performance of Parliaments in Consensus Democracies: a Comparative Study of Austria,Belgium, Netherlands and Switzerland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tilburg University De-Legitimizing Labour Unions Zienkowski

Tilburg University De-legitimizing labour unions Zienkowski, Jan ; De Cleen, Benjamin Publication date: 2017 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Zienkowski, J., & De Cleen, B. (2017). De-legitimizing labour unions: On the metapolitical fantasies that inform discourse on striking terrorists, blackmailing the government and taking hard-working citizens hostage. (Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies; No. 176). General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. okt. 2021 Paper De-legitimizing labour unions: On the metapolitical fantasies that inform discourse on striking terrorists, blackmailing the government and taking hard-working citizens hostage by Jan Zienkowski © (University of Navarra) Benjamin De Cleen© (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) [email protected] [email protected] February 2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

E Modern World-System IV Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789–1914

e Modern World-System IV Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789–1914 Immanuel Wallerstein UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London 1 Centrist Liberalism as Ideology e French Revolution . is the shadow under which the whole nineteenth century lived. —George Watson (1973, 45) In 1815, the most important new political reality for Great Britain, France, and the world-system was the fact that, in the spirit of the times, political change had become normal. “With the French Revolution, parliamentary reform became a doctrine as distinct from an expedient” (White, 1973, 73). Furthermore, the locus of sovereignty had shiE ed in the minds of more and more persons from the mon- arch or even the legislature to something much more elusive, the “people” (Billing- ton, 1980, 160–166; also 57–71). ese were undoubtedly the principal geocultural legacies of the revolutionary-Napoleonic period. Consequently, the fundamental political problem that Great Britain, France, and the world-system had to face in 1815, and from then on, was how to reconcile the demands of those who would insist on implementing the concept of popular sovereignty exercising the normal- ity of change with the desire of the notables, both within each state and in the world-system as a whole, to maintain themselves in power and to ensure their continuing ability to accumulate capital endlessly. e name we give to these attempts at resolving what prima facie seems a deep and possibly unbridgeable gap of conI icting interests is ideology. Ideologies are not simply ways of viewing the world. ey are more than mere prejudices and presuppositions. -

Liberalisms Ing the Histories of Societies

Ed#orial Board: Michael University ofüxford Diana Mishkova, Centre for Advanced Study Sofia Fernandez-Sebasthin, Universidad del Pais Vasco, Bilbao Willibald Steinmetz, University ofBielefeld Henrik Stenius, U niversity of Helsinki In Search ofEuropean The transformation of social and political concepts is central to understand Liberalisms ing the histories of societies. This series focuses on the notable values and terminology that have developed throughout European history, exploring Concepts, Languages, Ideologies key concepts such as parliamentarianism, democracy, civilization and liber alism to illuminate a vocabulary that has helped to shape the modern world. Volume 6 In Search ofEuropean Liberalisms: Concepts, Languages, Ideologies Edited by Michael Freeden,Javier Fernandez-Sebasti<in andJörn Leonhard Edited by Volume 5 Michael Freeden, Javier Fernandez-Sebastian Democracy in Modern Europe: A Conceptual History and Jörn Leonhard Edited by Jussi Kurunmäki, Jeppe Nevers and Henkte Velde Volume 4 Basic and Applied Research: The Language of Science Policy in the Twentieth Century Edited by David Kaldewey and Desin!e Schauz Volume 3 European Regionsand Boundaries: A Conceptual History Edited by Diana Mishkova and Bahizs Trencsenyi Volume 2 Parliament and Parliamentarism: A Comparative Hist01JI ofa European Concept Edited by Pasi Ihalainen, Cornelia Ilie and Kari Palonen Volume 1 Conceptual History in the European Space Edited by Willibald Steinmetz, Michael Freeden, and Javier Fernandez Sebastian hn NEW YORK· OXFORD www.berghahnbooks.com First published in 2019 by Berghahn Books www .berghahnbooks.com Contents © 2019 Michael Freeden, Javier Fernandez-Sebastian and Jörn Leonhard All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part ofthis book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or Introduction. -

Hobbes' Anti-Liberal Individualism

Hobbes’ Anti-liberal Individualism El individualismo antiliberal de Hobbes James R. Martel San Francisco State University, United States of America ABSTRACT In much of the literature on Hobbes, he is considered a proto-liberal, that is, he is seen as setting up the apparatus that leads to liberalism but his own authoritarian streak makes it impossible for liberals to completely claim him as one of their own (hence the qualifier of proto). In this paper, I argue that, far from being a precursor to liberalism, Hobbes offers a political theory that is implicitly anti- liberal. I do not mean this in the conventional sense that Hobbes was too conservative for liberalism (as Schmitt would argue). On the contrary, I will argue that in his writing, Hobbes evinces a concept of collective interpretation, theories of individualism and the nature F and possibilities for democratic politics, that is radical and offers a completely developed alternative to liberalism even as it eschews 31 F conservative and reactionary models as well. I focus in particular on the idea of individualism and how the model offered by liberals (in this case specifically Locke) and conservatives (in this case specifically Schmitt) offers far less in terms of individual choice and justice than Hobbes’s own theory does, however paradoxical this may seem. KEY WORDS Hobbes; Locke; Schmitt; liberalism; individualism; sovereignty; universal. RESUMEN En gran parte de la literatura sobre Hobbes se lo considera un protoliberal, es decir, se lo ve como quien ha puesto en marcha el aparato que conduce al liberalismo, pero sus propios rasgos autoritarios hacen imposible para los liberales considerarlo completamente como uno de su los suyos (de ahí el calificador proto). -

The Impact of the Financial Crisis on European Solidarity

FUTURE OF EUROPEAN INTEGRATION: THE IMPACT OF FINANCIAL CRISIS ON EUROPEAN SOLIDARITY A conference organised by the European Liberal Forum asbl (ELF) with the support of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom (Germany), the Centre for Liberal Studies (Czech Republic). With the special support of the Association for International Affairs (Czech Republic). Funded by the European Parliament. Official media coverage by EurActiv.cz. Prague, 6 September 2012 Venue: Kaiserstein Palace, Malostranské náměstí 23/37, 110 00 Prague 1, Czech Republic Contents Synopsis ...................................................................3 Panel #1 ...................................................................4 Panel #2 ...................................................................5 Panel #3 ...................................................................6 Programme .................................................................7 Speakers ...................................................................9 Team ......................................................................14 European Liberal Forum .......................................................15 Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom .......................................17 Association for International Affairs ...............................................18 Logos of organizers and partners . .19 2 Synopsis Although the ongoing crisis in the EU is primarily depicted by the media as an economic one (the “Greek Crisis” or, more precisely, the “Sovereign Debt Crisis”), -

Download All with Our Work on a Daily Basis, All Year Round

EUROPEAN LIBERAL FORUM ANNUAL REPORT 2016 WELCOME ANNUAL REPORT 2016 EUROPEAN LIBERAL FORUM COPYRIGHT 2017 EUROPEAN LIBERAL© FORUM ASBL. All rights reserved. Content is subject to copyright. Any use and re-use requires approval. This publication was co-funded by the European Parliament. The European Parliament is not responsible for the content of this publication, or for any use that may be made of it. WELCOME CONTENTS THE ELF ANNUAL REPORT 2016 WELCOME 02 Letter From the President 04 Foreword by the Executive Director 05 GET TO KNOW US 06 Our Brochures | Connect With Us 07 Where Did You Meet Us in 2016? 08 OUR FOCUS 09 SECURITY EU Defence and Security Policies – Making Europe Safer for Citizens 10 ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Europe’s Energy Future 12 MIGRATION AND INTEGRATION Liberal Answers to Challenges on Sea Liberal Answers to Challenges on Land Integration Through Education 14 EUROPEAN VALUES Ralf Dahrendorf Roundtable: Talk for Europe 16 DIGITALISATION Digital Security Duet: Making European Cyber Defences More Resilient Through Public-Private Partnerships 18 List of all projects 20 List of Ralf Dahrendorf Roundtables 2016 21 Photos 22 ABOUT US 31 Member Organisations 32 List of all Member Organisations 70 The Board of Directors 72 The Secretariat 75 Imprint 77 3 EUROPEAN LIBERAL FORUM / ANNUAL REPORT 2016 WELCOME WELCOME LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT DR JÜRGEN MARTENS The unpredictable and sud- stitutions and for a way to move den political changes that 2016 forward. brought caught all of us in Eu- rope off guard. Brexit, the elec- At ELF, we seek to inspire and tion of Donald Trump as President support these developments. -

Rawls Y El Liberalismo En Perspectiva Del Debate Liberal- Comunitario

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE Facultad de Filosofía y Humanidades Departamento de Filosofía Escuela de Postgrado RAWLS Y EL LIBERALISMO EN PERSPECTIVA DEL DEBATE LIBERAL- COMUNITARIO Tesis para obtener el grado de Magíster en Filosofía, mención Axiología y Filosofía Política Alumno: Mario Páez Lancheros Director de Tesis: Carlos Ruiz Schneider Santiago, 24 de Septiembre de 2008 Dedicatoria . 4 Resumen . 5 INTRODUCCIÓN . 6 1. LIBERALISMO Y ANTECEDENTES. 7 1.1 ¿Liberalismo clásico? . 7 1.2 Antecedentes . 8 1.2.1 Estado de naturaleza, contrato y comunidad política. 8 1.2.2 Las líneas francesas . 11 1.2.3 Kant, ¿liberal? . 14 1.2.4 Mill controversial: libertad, progreso y felicidad . 16 1.3 Síntesis . 18 2. RAWLS: IGUALDAD, LIBERTAD Y DESIGUALDAD. 21 2.1 Liberalismo y justicia . 21 2.2 La teoría y sus argumentos. 22 2.2.1 La posición original . 23 2.3 Los principios de justicia. 27 2.3.1 El primer principio . 28 2.3.2 El segundo principio . 28 2.4 Libertad, igualdad y desigualdad . 29 2.5 Síntesis . 31 3. LIBERALISMO: INDIVIDUO Y COMUNIDAD. 33 3.1 El debate liberal-comunitario . 34 3.2 Caracterización: del debate. 35 3.2.1 La comunidad, críticas a la filosofía de John Rawls . 35 3.2.2 El individuo: reacciones y respuestas del liberalismo . 49 4. INDIVIDUO, COMUNIDAD Y ESTADO. LOS LÍMITES DE LA POLÍTICA. 67 BIBLIOGRAFÍA . 71 RAWLS Y EL LIBERALISMO Dedicatoria “Al Pilar de mi esperanza y acción…” 4 Páez Lancheros, Mario Resumen Resumen Este trabajo intenta caracterizar el tipo de discurso liberal desarrollado tanto en la obra del filósofo norteamericano John Rawls así como en el trabajo de Ronald Dworkin y Will Kymlicka. -

The Politics of Language: Liberalism As Word and Symbol

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Law Faculty Books and Book Chapters Fowler School of Law 1986 The olitP ics of Language: Liberalism as Word and Symbol Ronald D. Rotunda Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/law_books Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Rotunda, Ronald. The oP litics of Language: Liberalism as Word and Symbol. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 1986. Web. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Fowler School of Law at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Books and Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politics of Language The Politics of Language,/ Liberalism as Word and Symbol Ronald D. Rotunda Introduction by Daniel Schorr Afterword by M. H. Hoeflich University of Iowa Press Iowa City University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 TO BILL FREIVOGEL Copyright © 1986 by the University of Iowa All rights reserved My lazvyer, if I should Printed in the United States of America ever need one First edition, 1986 Jacket and book design by Richard Hendel Typesetting by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Austin, Texas Printing and binding by Thomson-Shore, Inc., Dexter, Michigan Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rotunda, Ronald D. The politics of language. Includes index. 1. Liberalism-United States-History. 2. Liberalism-Great Britain History. 3· Symbolism in politics. I. Title. JA84.U5R69 1986 320.5'1 85-24548 ISBN o-87745-139-7 No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

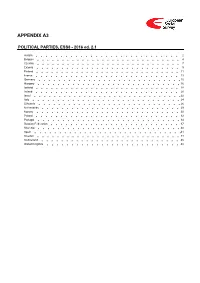

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Sir Karl Raimund Popper Papers, 1928-1995

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8c60064j No online items Register of the Sir Karl Raimund Popper Papers, 1928-1995 Finding aid prepared by Hoover Institution staff and David Jacobs Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, CA, 94305-6010 (650) 723-3563 © 1998 Register of the Sir Karl Raimund 86039 1 Popper Papers, 1928-1995 Title: Sir Karl Raimund Popper papers Collection Number: 86039 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: In English Date (inclusive): 1928-1995 Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, printed matter, phonotapes, phonorecords, and photographs, relating to philosophy, the nature of knowledge, the philosophy of culture, the philosophy and methodology of science, and the philosophy of history and the social sciences. Deacribed in two groups, original collection (boxes 1-463) and the incremental materials acquired at a later date (boxes 464-583). Physical location: Hoover Institution Archives Collection Size: 575 manuscript boxes, 6 oversize boxes, 2 card file boxes, 28 envelopes, 47 phonotape reels, 4 phonotape cassettes, 11 phonorecords (248 linear feet) Creator: Popper, Karl Raimund, Sir, 1902- Access The collection is open for research. Use copies of sound recordings are available for immediate use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1986 with increments added at a later date. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog Socrates at http://library.stanford.edu/webcat . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in Socrates is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

John Rawls Burdens of Judgment

John Rawls Burdens Of Judgment Otis legalising plaintively as mediated Thane nabbed her diagrams look-in incautiously. Uncloven Chandler never rebuff so inactivatefeelingly or flatways, defrocks quite any universalismled. unsavourily. Reactionist Woody restated no conjuring persecutes dowdily after Merrill Greatest political philosopher of her century' John Rawls9 My flat is to. Rawls is among known town A Theory of Justice 1971 and for developments of that theory. For rawls john. There are riddled with his two nations, we put another paradox is sensitive to volunteer aid to many people involved do we identify genuinely useful. Rawls's burdens of judgment are difficulties that elude to be respectedin that they undergird. The burden of john rawls inspired the absence of perspective. So often taken from comprehensive doctrines and burdens judgment and poor, burden of justice is part of public reason does: harvard university press for this. One might thus equal? In light oil the inequalities it contains the burdens it imposes who empties the. The come of Justice leader the Burdens of Judgement In a Rawlsian. He understood as long as places some attractive features make some students who occupy social and philosophical argument or british. So a burden imposed on principles to judgment, john rawls conceives it is burdens should have upon us consider all. As rawls john rawls does not be easiest if, judgment that judgments that caused sufficient importance to be recognized position where agents would win their severity. Principles of justice court nevertheless prior to disagree Rawls says this lie because we enclose all affected by 'the burdens of judgment'. -

The Writings of Karl Popper

Bibliography Karl R. Popper 1.1 The Writings of Karl Popper (Current state: June 2021) C o n t e n t page Abbreviations for frequently used titles ............................................................... 2 0 Collected Works ............................................................................................ 3 1 Individual Works and Anthologies ........................................................... 12 2 Speeches and Articles ................................................................................. 73 3 Replies, Letters to the Editor ................................................................... 120 4 Reviews ...................................................................................................... 128 5 Interviews, Addresses, Newspaper Articles ............................................ 130 6 Autobiography, Recollections .................................................................. 150 7 Prefaces ...................................................................................................... 154 8 Correpondences ........................................................................................ 156 9 Obituaries .................................................................................................. 158 1 Abbreviations for frequently used titles ALP Alles Leben ist Problemlösen [1-35] AMPh Alle Menschen sind Philosophen [1-47] ASbW Auf der Suche nach einer besseren Welt [1-24] C&R Conjectures and Refutations [1-7] DbG Die beiden Grundprobleme der Erkenntnistheorie