Slowing Routing Table Growth by Filtering Based on Address Allocation Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

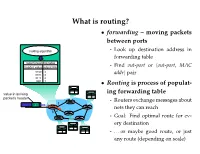

What Is Routing?

What is routing? • forwarding – moving packets between ports - Look up destination address in forwarding table - Find out-port or hout-port, MAC addri pair • Routing is process of populat- ing forwarding table - Routers exchange messages about nets they can reach - Goal: Find optimal route for ev- ery destination - . or maybe good route, or just any route (depending on scale) Routing algorithm properties • Static vs. dynamic - Static: routes change slowly over time - Dynamic: automatically adjust to quickly changing network conditions • Global vs. decentralized - Global: All routers have complete topology - Decentralized: Only know neighbors & what they tell you • Intra-domain vs. Inter-domain routing - Intra-: All routers under same administrative control - Intra-: Scale to ∼100 networks (e.g., campus like Stanford) - Inter-: Decentralized, scale to Internet Optimality A 6 1 3 2 F 1 E B 4 1 9 C D • View network as a graph • Assign cost to each edge - Can be based on latency, b/w, utilization, queue length, . • Problem: Find lowest cost path between two nodes - Must be computed in distributed way Distance Vector • Local routing algorithm • Each node maintains a set of triples - (Destination, Cost, NextHop) • Exchange updates w. directly connected neighbors - periodically (on the order of several seconds to minutes) - whenever table changes (called triggered update) • Each update is a list of pairs: - (Destination, Cost) • Update local table if receive a “better” route - smaller cost - from newly connected/available neighbor • Refresh existing -

The Routing Table V1.12 – Aaron Balchunas 1

The Routing Table v1.12 – Aaron Balchunas 1 - The Routing Table - Routing Table Basics Routing is the process of sending a packet of information from one network to another network. Thus, routes are usually based on the destination network, and not the destination host (host routes can exist, but are used only in rare circumstances). To route, routers build Routing Tables that contain the following: • The destination network and subnet mask • The “next hop” router to get to the destination network • Routing metrics and Administrative Distance The routing table is concerned with two types of protocols: • A routed protocol is a layer 3 protocol that applies logical addresses to devices and routes data between networks. Examples would be IP and IPX. • A routing protocol dynamically builds the network, topology, and next hop information in routing tables. Examples would be RIP, IGRP, OSPF, etc. To determine the best route to a destination, a router considers three elements (in this order): • Prefix-Length • Metric (within a routing protocol) • Administrative Distance (between separate routing protocols) Prefix-length is the number of bits used to identify the network, and is used to determine the most specific route. A longer prefix-length indicates a more specific route. For example, assume we are trying to reach a host address of 10.1.5.2/24. If we had routes to the following networks in the routing table: 10.1.5.0/24 10.0.0.0/8 The router will do a bit-by-bit comparison to find the most specific route (i.e., longest matching prefix). -

P2P Resource Sharing in Wired/Wireless Mixed Networks 1

INT J COMPUT COMMUN, ISSN 1841-9836 Vol.7 (2012), No. 4 (November), pp. 696-708 P2P Resource Sharing in Wired/Wireless Mixed Networks J. Liao Jianwei Liao College of Computer and Information Science Southwest University of China 400715, Beibei, Chongqing, China E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents a new routing protocol called Manager-based Routing Protocol (MBRP) for sharing resources in wired/wireless mixed networks. MBRP specifies a manager node for a designated sub-network (called as a group), in which all nodes have the similar connection properties; then all manager nodes are employed to construct the backbone overlay network with ring topology. The manager nodes act as the proxies between the internal nodes in the group and the external world, that is not only for centralized management of all nodes to a certain extent, but also for avoiding the messages flooding in the whole network. The experimental results show that compared with Gnutella2, which uses super-peers to perform similar management work, the proposed MBRP has less lookup overhead including lookup latency and lookup hop count in the most of cases. Besides, the experiments also indicate that MBRP has well configurability and good scaling properties. In a word, MBRP has less transmission cost of the shared file data, and the latency for locating the sharing resources can be reduced to a great extent in the wired/wireless mixed networks. Keywords: wired/wireless mixed network, resource sharing, manager-based routing protocol, backbone overlay network, peer-to-peer. 1 Introduction Peer-to-Peer technology (P2P) is a widely used network technology, the typical P2P network relies on the computing power and bandwidth of all participant nodes, rather than a few gathered and dedicated servers for central coordination [1, 2]. -

Lab 5.5.2: Examining a Route

Lab 5.5.2: Examining a Route Topology Diagram Addressing Table Device Interface IP Address Subnet Mask Default Gateway S0/0/0 10.10.10.6 255.255.255.252 N/A R1-ISP Fa0/0 192.168.254.253 255.255.255.0 N/A S0/0/0 10.10.10.5 255.255.255.252 10.10.10.6 R2-Central Fa0/0 172.16.255.254 255.255.0.0 N/A N/A 192.168.254.254 255.255.255.0 192.168.254.253 Eagle Server N/A 172.31.24.254 255.255.255.0 N/A host Pod# A N/A 172.16. Pod#.1 255.255.0.0 172.16.255.254 host Pod# B N/A 172.16. Pod#. 2 255.255.0.0 172.16.255.254 S1-Central N/A 172.16.254.1 255.255.0.0 172.16.255.254 All contents are Copyright © 1992–2007 Cisco Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. This document is Cisco Public Information. Page 1 of 7 CCNA Exploration Network Fundamentals: OSI Network Layer Lab 5.5.1: Examining a Route Learning Objectives Upon completion of this lab, you will be able to: • Use the route command to modify a Windows computer routing table. • Use a Windows Telnet client command telnet to connect to a Cisco router. • Examine router routes using basic Cisco IOS commands. Background For packets to travel across a network, a device must know the route to the destination network. This lab will compare how routes are used in Windows computers and the Cisco router. -

Routing Tables

Routing Tables A routing table is a grouping of information stored on a networked computer or network router that includes a list of routes to various network destinations. The data is normally stored in a database table and in more advanced configurations includes performance metrics associated with the routes stored in the table. Additional information stored in the table will include the network topology closest to the router. Although a routing table is routinely updated by network routing protocols, static entries can be made through manual action on the part of a network administrator. How Does a Routing Table Work? Routing tables work similar to how the post office delivers mail. When a network node on the Internet or a local network needs to send information to another node, it first requires a general idea of where to send the information. If the destination node or address is not connected directly to the network node, then the information has to be sent via other network nodes. In order to save resources, most local area network nodes will not maintain a complex routing table. Instead, they will send IP packets of information to a local network gateway. The gateway maintains the primary routing table for the network and will send the data packet to the desired location. In order to maintain a record of how to route information, the gateway will use a routing table that keeps track of the appropriate destination for outgoing data packets. All routing tables maintain routing table lists for the reachable destinations from the router’s location. -

Introduction to the Border Gateway Protocol – Case Study Using GNS3

Introduction to The Border Gateway Protocol – Case Study using GNS3 Sreenivasan Narasimhan1, Haniph Latchman2 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Florida, Gainesville, USA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract – As the internet evolves to become a vital resource for many organizations, configuring The Border Gateway protocol (BGP) as an exterior gateway protocol in order to connect to the Internet Service Providers (ISP) is crucial. The BGP system exchanges network reachability information with other BGP peers from which Autonomous System-level policy decisions can be made. Hence, BGP can also be described as Inter-Domain Routing (Inter-Autonomous System) Protocol. It guarantees loop-free exchange of information between BGP peers. Enterprises need to connect to two or more ISPs in order to provide redundancy as well as to improve efficiency. This is called Multihoming and is an important feature provided by BGP. In this way, organizations do not have to be constrained by the routing policy decisions of a particular ISP. BGP, unlike many of the other routing protocols is not used to learn about routes but to provide greater flow control between competitive Autonomous Systems. In this paper, we present a study on BGP, use a network simulator to configure BGP and implement its route-manipulation techniques. Index Terms – Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), Internet Service Provider (ISP), Autonomous System, Multihoming, GNS3. 1. INTRODUCTION Figure 1. Internet using BGP [2]. Routing protocols are broadly classified into two types – Link State In the figure, AS 65500 learns about the route 172.18.0.0/16 through routing (LSR) protocol and Distance Vector (DV) routing protocol. -

The Routing Table Lookup Process

The Routing Table Part 2 – The Routing Table Lookup Process By Rick Graziani Cisco Networking Academy [email protected] Updated: Oct. 10, 2002 This document is the second of two parts dealing with the routing table. Part I discussed the structure of the routing table, and how routes are created. Part II will discuss how the routing table lookup process finds the “best” route within the routing table. What happens when a router receives an IP packet, examines the IP destination address and looks that address up in the routing table? How does the router decide which route in the routing table is the best match? What affect does the subnet mask have on the routing table? How does the router decide whether or not to use a supernet or default route if there is not a better match? We will answer these questions and more in this document. The network we will be using is a simple three router network. RouterA and Router B share the common major network 172.16.0.0/24. RouterB and RouterC are connected by the 192.168.1.0/24 network. You will notice that RouterC also has a 172.16.4.0/24 subnet which is disconnected, or discontiguous, from the rest of the 172.16.0.0 network. 172.16.1.0/24 172.16.3.0/24 172.16.4.0/24 .1 fa0 .1 fa0 .1 fa0 .1 172.16.2.0/24 .2 .1 192.168.1.0/24 .2 s0 s0 s1 s0 Router A Router B Router C Most of this information is best explained by using examples. -

Analyzing the Internet's BGP Routing Table

Analyzing the Internet’s BGP Routing Table Geoff Huston January 2001 The Internet continues along a path of seeming inexorable growth, at a rate which has, at a minimum, doubled in size each year. How big it needs to be to meet future demands remains an area of somewhat vague speculation. Of more direct interest in the question of whether the basic elements of the Internet can be extended to meet such levels of future demand, whatever they may be. To rephrase this question, are there inherent limitations in the technology of the Internet, or its architecture of deployment that may impact on the continued growth of the Internet to meet ever expanding levels of demand? There are a number of potential areas to search for such limitations. These include the capacity of transmission systems, the switching capacity of routers, the continued availability of addresses and the capability of the routing system to produce a stable view of the overall topology of the network. In this article we will examine the Internet’s routing system and the longer term growth trends that are visible within this system. The structure of the global Internet can be likened to a loose coalition of semi-autonomous constituent networks. Each of these networks operates with its own policies, prices, services and customers. Each network makes independent decisions about where and how to secure supply of various components that are needed to create the network service. The cement that binds these networks into a cohesive whole is the use of a common address space and a common view of routing. -

RIP: Routing Information Protocol a Routing Protocol Based on the Distance-Vector Algorithm

Laboratory 6 RIP: Routing Information Protocol A Routing Protocol Based on the Distance-Vector Algorithm Objective The objective of this lab is to configure and analyze the performance of the Routing Information Protocol (RIP) model. Overview A router in the network needs to be able to look at a packet’s destination address and then determine which of the output ports is the best choice to get the packet to that address. The router makes this decision by consulting a forwarding table. The fundamental problem of routing is: How do routers acquire the information in their forwarding tables? Routing algorithms are required to build the routing tables and hence forwarding tables. The basic problem of routing is to find the lowest-cost path between any two nodes, where the cost of a path equals the sum of the costs of all the edges that make up the path. Routing is achieved in most practical networks by running routing protocols among the nodes. The protocols provide a distributed, dynamic way to solve the problem of finding the lowest-cost path in the presence of link and node failures and changing edge costs. One of the main classes of routing algorithms is the distance-vector algorithm. Each node constructs a vector containing the distances (costs) to all other nodes and distributes that vector to its immediate neighbors. RIP is the canonical example of a routing protocol built on the distance-vector algorithm. Routers running RIP send their advertisements regularly (e.g., every 30 seconds). A router also sends an update message whenever a triggered update from another router causes it to change its routing table. -

Lab 2.8.1: Basic Static Route Configuration

Lab 2.8.1: Basic Static Route Configuration Topology Diagram Addressing Table Device Interface IP Address Subnet Mask Default Gateway Fa0/0 172.16.3.1 255.255.255.0 N/A R1 S0/0/0 172.16.2.1 255.255.255.0 N/A Fa0/0 172.16.1.1 255.255.255.0 N/A R2 S0/0/0 172.16.2.2 255.255.255.0 N/A S0/0/1 192.168.1.2 255.255.255.0 N/A FA0/0 192.168.2.1 255.255.255.0 N/A R3 S0/0/1 192.168.1.1 255.255.255.0 N/A PC1 NIC 172.16.3.10 255.255.255.0 172.16.3.1 PC2 NIC 172.16.1.10 255.255.255.0 172.16.1.1 PC3 NIC 192.168.2.10 255.255.255.0 192.168.2.1 Learning Objectives Upon completion of this lab, you will be able to: • Cable a network according to the Topology Diagram. • Erase the startup configuration and reload a router to the default state. • Perform basic configuration tasks on a router. All contents are Copyright © 1992–2007 Cisco Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. This document is Cisco Public Information. Page 1 of 20 CCNA Exploration Routing Protocols and Concepts: Static Routing Lab 2.8.1: Basic Static Route Configuration • Interpret debug ip routing output. • Configure and activate Serial and Ethernet interfaces. • Test connectivity. • Gather information to discover causes for lack of connectivity between devices. • Configure a static route using an intermediate address. -

IP Switching Cisco Express Forwarding Configuration Guide, Cisco IOS XE Release 3SE (Catalyst 3650 Switches)

Cisco Express Forwarding This module contains an overview of the Cisco Express Forwarding feature. Cisco Express Forwarding is an advanced Layer 3 IP switching technology. It optimizes network performance and scalability for all kinds of networks: those that carry small amounts of traffic and those that carry large amounts of traffic in complex patterns, such as the Internet and networks characterized by intensive web-based applications or interactive sessions. • Finding Feature Information, page 1 • Information About CEF, page 1 • How to Configure CEF, page 9 • Configuration Examples for CEF, page 9 • Additional References, page 9 • Feature Information for Cisco Express Forwarding, page 11 Finding Feature Information Your software release may not support all the features documented in this module. For the latest caveats and feature information, see Bug Search Tool and the release notes for your platform and software release. To find information about the features documented in this module, and to see a list of the releases in which each feature is supported, see the feature information table at the end of this module. Use Cisco Feature Navigator to find information about platform support and Cisco software image support. To access Cisco Feature Navigator, go to www.cisco.com/go/cfn. An account on Cisco.com is not required. Information About CEF This document presents the following topics to explain the changes you will find with the implementation of the Cisco Express Forwarding enhancements. This information should be helpful as you transition to Cisco IOS software that includes the Cisco Express Forwarding and MFI enhancements. The fifth and sixth topics provide information about the CLI changes implemented as part of the Cisco Express Forwarding enhancements. -

Survey of Search and Replication Schemes in Unstructured P2p Networks

SURVEY OF SEARCH AND REPLICATION SCHEMES IN UNSTRUCTURED P2P NETWORKS Sabu M. Thampi Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Rajagiri School of Engineering and Technology. Rajagiri Valley, Kakkanad, Kochi- 682039, Kerala (India) Tel: +91-484-2427835 E-mail: [email protected] Chandra Sekaran. K Department of Computer Engineering, National Institute of Technology Karnataka. Surathkal-575025, Karnataka (India) Tel: +91-824-2474000 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract P2P computing lifts taxing issues in various areas of computer science. The largely used decentralized unstructured P2P systems are ad hoc in nature and present a number of research challenges. In this paper, we provide a comprehensive theoretical survey of various state-of-the-art search and replication schemes in unstructured P2P networks for file-sharing applications. The classifications of search and replication techniques and their advantages and disadvantages are briefly explained. Finally, the various issues on searching and replication for unstructured P2P networks are discussed. Keywords: Replication, Searching, Unstructured P2P network. 1 1. Introduction Computing has passed through many transformations since the birth of the first computing machines. A centralized solution has one component that is shared by users all the time. All resources are accessible, but there is a single point of control as well as a single point of failure. A distributed system is a group of autonomous computers connected to a computer network, which appears to the clients of the system as a single computer. Distributed system software allows computers to manage their activities and to share the resources of the system, so that clients recognize the system as a single, integrated computing facility.