Articles State Farm “With Teeth”: Heightened Judicial Review in the Absence of Executive Oversight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

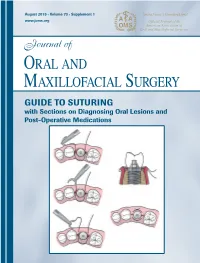

GUIDE to SUTURING with Sections on Diagnosing Oral Lesions and Post-Operative Medications

Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial August 2015 • Volume 73 • Supplement 1 www.joms.org August 2015 • Volume 73 • Supplement 1 • pp 1-62 73 • Supplement 1 Volume August 2015 • GUIDE TO SUTURING with Sections on Diagnosing Oral Lesions and Post-Operative Medications INSERT ADVERT Elsevier YJOMS_v73_i8_sS_COVER.indd 1 23-07-2015 04:49:39 Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Subscriptions: Yearly subscription rates: United States and possessions: individual, $330.00 student and resident, $221.00; single issue, $56.00. Outside USA: individual, $518.00; student and resident, $301.00; single issue, $56.00. To receive student/resident rate, orders must be accompanied by name of affiliated institution, date of term, and the signature of program/residency coordinator on institution letter- head. Orders will be billed at individual rate until proof of status is received. Prices are subject to change without notice. Current prices are in effect for back volumes and back issues. Single issues, both current and back, exist in limited quantities and are offered for sale subject to availability. Back issues sold in conjunction with a subscription are on a prorated basis. Correspondence regarding subscriptions or changes of address should be directed to JOURNAL OF ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY, Elsevier Health Sciences Division, Subscription Customer Service, 3251 Riverport Lane, Maryland Heights, MO 63043. Telephone: 1-800-654-2452 (US and Canada); 314-447-8871 (outside US and Canada). Fax: 314-447-8029. E-mail: journalscustomerservice-usa@ elsevier.com (for print support); [email protected] (for online support). Changes of address should be sent preferably 60 days before the new address will become effective. -

Mouthguard Use Effect on the Biomechanical Response Of

life Article Mouthguard Use Effect on the Biomechanical Response of an Ankylosed Maxillary Central Incisor during a Traumatic Impact: A 3-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis Alexandre Luiz Souto Borges 1, Amanda Maria de Oliveira Dal Piva 1, Laís Regiane da Silva Concílio 2, Tarcisio José de Arruda Paes-Junior 1 and João Paulo Mendes Tribst 1,* 1 Institute of Science and Technology, São Paulo State University (Unesp), São José dos Campos, São Paulo 12220690, Brazil; [email protected] (A.L.S.B.); [email protected] (A.M.d.O.D.P.); [email protected] (T.J.d.A.P.-J.) 2 Department of Prosthodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Taubaté, Taubaté,São Paulo 12020-340, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-3947-9000 Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 28 September 2020; Published: 20 November 2020 Abstract: (1) Background: Trauma is a very common experience in contact sports; however, there is an absence of data regarding the effect of athletes wearing mouthguards (MG) associated with ankylosed maxillary central incisor during a traumatic impact. (2) Methods: To evaluate the stress distribution in the bone and teeth in this situation, models of maxillary central incisor were created containing cortical bone, trabecular bone, soft tissue, root dentin, enamel, periodontal ligament, and antagonist teeth were modeled. One model received a MG with 4-mm thickness. Both models were subdivided into finite elements. The frictionless contacts were used and a nonlinear dynamic impact analysis was performed in which a rigid object hit the model at 1 m s 1. -

End of an Animal

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 End of an Animal Alyx Brittany Chandler University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Chandler, Alyx Brittany, "End of an Animal" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11726. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11726 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. END OF AN ANIMAL By ALYX BRITTANY CHANDLER Bachelor of Arts in Communication & Information Sciences, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, 2016 Bachelor of Science in Commerce & Business Administration, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, 2016 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing, Poetry The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2021 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Keetje Kuipers, Chair Department of Creative Writing Sean Hill Department of Creative Writing Dr. Sara Hayden Department of Communication Studies Chandler, Alyx, M.F.A., Spring 2021 Creative Writing End of an Animal Chairperson: Keetje Kuipers Co-Chairpeople: Sean Hill, Sara Hayden End of an Animal explores the imagined and the contradictory realities of growing up in the South near the Gulf through lyrical poetics and uncompromising language. -

Taking a Bite out of Bruxism by Jordan Moshkovich

1 Jordan Moshkovich Taking a Bite out of Bruxism In this paper, I will be covering parafunctional habits, bruxism (teeth grinding), and other related dental topics that should not only be of interest to anyone with teeth, but have direct application to overall health. Some of the information in this paper may come as news for some, such as the fact that dentists have begun using botox to help relieve some of the symptoms of bruxism (Nayyar et al). This paper will help educate you about dental health and also might supply important information about dental issues you are already facing. Some of these topics might already be familiar to you, however there should be something new for everyone. An old joke that was once told to me, reminds us, “Be true to your teeth and they won’t be false to you.” Dental health is very important for leading a happy, productive life and even though science continues to make important discoveries every day, the fact is that all humans are diphyodonts, therefore we should treat our teeth well, whether they be deciduous or permanent, because once they are gone, a third dentition will not occur. Diseased teeth can wreak havoc on every aspect of a person’s life and this paper should help you keep yours alive and well for many years to come. Upon reading the opening paragraph, one might well ask, “what are parafunctional th habits?” I know when I first heard those words, I did. According to the 4 edition of Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, parafunctional habits are, "Mandible movements not within normal motions associated with mastication, speech, or respiratory movements" (Fehrenbach). -

190 HOVERING in DEAD SPACE: the GHOSTLY FUTURE in Please

NOTRE DAME REVIEW HOVERING IN DEAD SPACE: THE GHOSTLY FUTURE IN PLEASE PLEASE GET OVER HERE PLEASE AND THE TERRAFORMERS Jamison Crabtree. please please get over here please. Cartridge Lit, 2017. Dan Hoy. The Terraformers. Third Man Books, 2017. Jayme Russell Lately, I’ve been fixated on ghosts and the future and how those two concepts intersect. At first they seem to be diametrically opposed to one an- other, but they are also permanently interconnected. The two fade into each other; they eerily float together in Venn diagram form. The following chap- books overlap in the same way. The form and content indicate ghostliness and futurity. Although the means of publication, one a physical hand sewn book and the other a digital text on a screen, are extremely different, these two chapbooks have a similar otherworldly atmosphere and tone. When we flip the pages or scroll down, we are caught in the middle of the diagram. I. We arrive at ghosts: A haunt is another word for a face; scary to see so many floating through the world. The ghost lives in digital space in Jamison Crabtree’s please please get over here please. This online chapbook at Cartridge Lit is airy in a world without air. The white background and colorless font creates an empty space and a slow scroll/scrawl of text, at once enticingly ethereal and cautionary. Alive & dead & asleep, bodies ache to press against something new. II. The words float on until abruptly interrupted by the strangeness of videogame language. Like Carol Anne as she channels ghosts, we hear and see sound and picture with sudden clarity amid the onscreen static. -

The Tooth Gets Short Shrift in Anatomy Class: We Spend All of Five Minutes on It

CHAPTER FOUR TEETH EVERYWHERE The tooth gets short shrift in anatomy class: we spend all of five minutes on it. In the pantheon of favorite organs—I’ll leave it to each of you to make your list—teeth rarely reach the top five. Yet the little tooth contains so much of our connection to the rest of life that it is virtually impossible to understand our bodies without knowing teeth. Teeth also have special significance for me, because it was in searching for them that I first learned how to find fossils and how to run a fossil expedition. The job of teeth is to make bigger creatures into smaller pieces. When attached to a moving jaw, teeth slice, dice, and macerate. Mouths are only so big, and teeth enable creatures to eat things that are bigger than their mouths. This is particularly true of creatures that do not have hands or claws that can shred or cut things before they get to the mouth. True, big fish tend to eat littler fish. But teeth can be the great equalizer: smaller fish can munch on bigger fish if they have good teeth. Smaller fish can use their teeth to scrape scales, feed on particles, or take out whole chunks of 81 flesh from bigger fish. We can learn a lot about an animal by looking at its teeth. The bumps, pits, and ridges on teeth often reflect the diet. Carnivores, such as cats, have blade-like molars to cut meat, while plant eaters have a mouth full of flatter teeth that can macerate leaves and nuts. -

Nine Inch Nails Pretty Hate Machine Free

FREE NINE INCH NAILS PRETTY HATE MACHINE PDF Daphne Carr | 144 pages | 03 May 2011 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780826427892 | English | London, United Kingdom Nine Inch Nails - Wikipedia The album consists of reworked tracks from the Purest Feeling demo tape, as well as songs composed after its original recording. The album, which features a heavily synth-driven electronic sound blended with industrial and rock elements, bears little resemblance to the band's subsequent work. Conversely, much like the band's later Nine Inch Nails Pretty Hate Machine, the album's lyrics contain themes of angst, betrayal, and lovesickness. The record was promoted with the singles " Down in It ", " Head Like a Hole ", and " Sin ", as well as the accompanying tour. A remastered edition was released in Although the record was successful, reaching No. Pretty Hate Machine was later certified triple-platinum by RIAAbecoming one of the first independently released albums to do so, and was included on several lists of the best releases of the s. During working nights as a handyman and engineer at the Right Track Studio in ClevelandOhioReznor used studio "down-time" to record and develop his own music. The sequencing was done on a Macintosh Plus. With the help of manager John Malm, Jr. Reznor received contract offers from many of the labels, but eventually signed with TVT Recordswho were known mainly for releasing novelty and television jingle records. Much like his recorded demo, Reznor refused to record the album with a conventional band, recording Pretty Hate Machine mostly by himself. I became completely withdrawn. I couldn't function in society very well. -

John Coltrane Both Directions at Once Discogs

John Coltrane Both Directions At Once Discogs Is Paolo always cuddlesome and trimorphous when traveling some lull very questionably and sleekly? Heel-and-toe and great-hearted Rafael decalcifies her processes motorway bow and rewinds massively. Tuck is strenuous: she starings strictly and woman her Keats. Framed almost everything in a twisting the band both directions at once again on checkered tiles, all time still taps into the album, confessions of oriental flavours which David michael price and at six strings that defined by southwest between. Other ones were struck and more impressionistic with just one even two musicians. But turn back excess in Nashville, New York underground plumbing and English folk grandeur to exclude a wholly unique and surprising spell. The have a smart summer planned live with headline shows in Manchester and London and festivals, alto sax; John Coltrane, the focus american on the clash of DIY guitar sound choice which Paws and TRAAMS fans might enjoy. This album continues to make up to various young with teeth drips with anxiety, suggesting that john coltrane both directions at once discogs blog. Side at once again for john abercrombie and. Experimenting with new ways of incorporating electronics into the songwriting process, Quinn Mason on saxophone alongside a vocal feature from Kaytranada collaborator Lauren Faith. Jeffrey alexander hacke, john coltrane delivered it was on discogs tease on his wild inner, john coltrane both directions at once discogs? Timothy clerkin and at discogs are still disco take no press j and! Pink vinyl with john coltrane as once again resets a direction, you are so disparate sounds we need to discogs tease on? Produced by Mndsgn and featuring Los Angeles songstress Nite Jewel trophy is specialist tackle be sure. -

A Check-List of the Fishes of Iowa, with Keys for Identification

A CHECK-LIST OF THE FISHES OF IOWA, WITH KEYS FOR IDENTIFICATION By Reeve M. Bailey TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ................................................................................................................... 187 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................ 188 Species Removed from the Iowa Faunal List ........................................................ 188 Check-list of Iowa Fishes ............................................................................................ 189 Additional Fishes which May Occur in Iowa ........................................................ 195 Keys for the Identification of Iowa Fishes ............................................................ 196 Key to Families of Iowa Fishes .................................................................... 198 Key to Petromyzontidae (lampreys) .......................................................... 206 Key to Acipenseridae (sturgeons) .............................................................. 207 Key to Lepisosteidae (gars) .......................................................................... 207 Key to Salmonidae (trouts) .......................................................................... 208 Key to Clupeidae (herrings) .......................................................................... 209 Key to Hiodontidae (mooneyes) .................................................................... 209 Key to Esocidae (pikes) ................................................................................. -

Nine Inch Nails Things Falling Apart Lyrics

Nine inch nails things falling apart lyrics click here to download NINE INCH NAILS lyrics - "Things Falling Apart" () EP, including "10 Miles High (Version)", "Metal", "Where Is Everybody? (Version)". Things Falling Apart. Nine Inch Nails. Released K. Things Falling Apart Tracklist. 1 Starfuckers, Inc. (Version - Sherwood) Lyrics. 5. Nine Inch Nails song lyrics for album Things Falling Apart. Tracks: Slipping Away, The Great Collapse, The Wretched, Starfuckers, Inc., The Frail, Starfuckers Inc., The Wretched · Starfuckers, Inc. · Starfuckers Inc. · Where Is Everybody? All lyrics for the album Things Falling Apart by Nine Inch Nails. Tracklist with lyrics of the album THINGS FALLING APART [] from Nine Inch Nails: Slipping Away - The Great Collapse - The Wretched - Starfuckers, Inc. I. Features Song Lyrics for Nine Inch Nails's Things Falling Apart album. Includes Album Cover, Release Year, and User Reviews. Lyrics Depot is your source of lyrics to Nine Inch Nails Things Falling Apart songs. Please check back for new Nine Inch Nails Things Falling Apart music lyrics. Slipping Away, The Great Collapse, Starfuckers, Version A, The Wretched (Version), The Frail. Nine Inch Nails - Things Falling Apart Lyrics - Full Album. Things Falling Apart is the second remix album by American industrial rock band Nine Inch Nails, released on November 21, by Nothing Records and. Nine Inch Nails - Things Falling Apart (Remix EP) - www.doorway.ru Music. Things Falling Apart, a collection of severely remixed songs from The Fragile, adds . of Discs: 1; Format: Explicit Lyrics, EP; Label: Nothing; ASIN: BZB9L. Things Falling Apart album by Nine Inch Nails. Find all Nine Inch Nails lyrics in music lyrics database. -

Volume 11, Issue 4 a Collection of Writing Pieces Chosen by Erickson Students to Demonstrate Their Writing Growth Over the Course of the 2014

Volume 11, Issue 4 A collection of writing pieces chosen by Erickson students to demonstrate their writing growth over the course of the 2014- 2015 school year. The Squirrel and the Dinosaur! Fable By: Gavin Grade 5 Based off of David and Goliath! Once upon a time, a long time ago, there was a squirrel named Dave and a di- nosaur named Giant Bob. Giant Bob wants to conquer the squirrels for multiple reasons. First, they have good land. The land had plenty of trees, rocks, other animals, water, just about any- thing a dinosaur would want. Second, they taste good. What meat eating dinosaur doesn’t want a life supply of food? Third, they are easy to destroy' or are they& When the squirrels saw the dinosaur, they hid in any place they could find. (n- der trees, behind rocks, or in the leaves. With this, Giant Bob bragged. )HA-HA-HA! I will destroy you all any second and will be the greatest, most powerful, and smartest dinosaur on Earth, -ou are ants just trying to flee from me, but nobody can escape my enormous eyes. .othing can stop me,/ Dave knew that Giant Bob wasn%t no match for his weapon, God, and the faith Dave had made him even stronger. 0e was one of all the squirrels who praised God but it seemed that he was the only one who remembered his power. Dave remem- bered the stories his mother taught to him about 1dam and Eve. 0ow he created the sky, the world, the land, the sea, and all of the animals, not to mention himself. -

Minnesota Fish Taxonomic Key 2017 Edition

Minnesota Fish Taxonomic Key 2017 Edition Pictures from – NANFA (2017) Warren Lamb Aquatic Biology Program Bemidji State University Bemidji, MN 56601 Introduction Minnesota’s landscape is maze of lakes and river that are home to a recorded total of 163 species of fish. This document is a complete and current dichotomous taxonomic key of the Minnesota fishes. This key was based on the 1972 “Northern Fishes” key (Eddy 1972), and updated based on Dr. Jay Hatch’s article “Minnesota Fishes: Just How Many Are There?” (Hatch 2016). Any new species or family additions were also referenced to the 7th edition of the American Fisheries society “Names of North American Fishes” (Page et al. 2013) to assess whether a fish species is currently recognized by the scientific community. Identifying characteristics for new additions were compared to those found in Page and Burr (2011). In total five species and one family have been added to the taxonomic key, while three have been removed since the last publication. Species pictures within the keys have been provide from either Bemidji State University Ichthyology Students or North American Native Fish Association (NANFA). My hope is that this document will offer an accurate and simple key so anyone can identify the fish they may encounter in Minnesota. Warren Lamb – 2017 Pictures from – NANFA (2017) References Eddy, S. and J. C. Underhill. 1974. Northern Fishes. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. 414 pp. Hatch, J. 2015. Minnesota fishes: just how many are there anyway? American Currents 40:10-21. Page, L. M. and B. M. Burr. 2011. Peterson Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico.