BULGARIAN MONUMENTS in BUCHAREST and ROME Lina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sintid Esta Endetcha Que Quema El Corasson a Judeo-Spanish Epic Poem in Rhyme and Meter, Lamenting the Brutality of Invading Russians Toward the Jews in Bulgaria

e-ISSN 2340-2547 • www.meahhebreo.com MEAH. Sección Hebreo | vol. 63 | 2014 | 111-129 111 www.meahhebreo.com Sintid esta endetcha que quema el corasson A Judeo-Spanish epic poem in rhyme and meter, lamenting the brutality of invading Russians toward the Jews in Bulgaria Sintid esta endetcha que quema el corasson Un poema épico en judeoespañol para lamentar la brutalidad de los invasores rusos hacia los judíos en Bulgaria Michael Studemund-Halévy [email protected] Institut für die Geschichte der deutschen Juden, Hamburg Recibido: 29/05/2013 | Aceptado: 28/02/2014 Resumen Abstract En el presente artículo se publica y estudia The article publish and studies a kopla del una kopla del felek en lettras rashíes i latinas felek illustrating the Russo-Turkish war con- acerca de la guerra ruso-turca y la destrucción cerning the destruction of the Jewish com- de la comunidad judía de Karnabat. Los textos munity of Karnobat. The texts come from the proceden de los Archivos Nacionales de Sofia National Archives of Sofia and the Plovdiv y de la Biblioteca Muncipial de Plovdiv. Muncipalo Library Ivan Vazov. Palabras clave: Endecha, kopla del felek, Keywords: Dirge, Kopla del Felek, Yosef Hay- Yosef Hayim Benrey, Albert Confino, Judezmo, im Benrey, Albert Confino, Judezmo, Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Karnabat, guerra ruso-turca, edición Karnobat, Russo-Turkish War, Edition of texts. de textos. Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Fritz Thyssen Foundation for financing my fieldwork in Bulgaria, and express my gratitude to: Municipal Library Ivan Vazov/Plovdiv (Dorothée Kiforova), National Ar- chives/Sofia (Vania Gezenko) and Jewish National Library/Jerusalem (Ofra Lieberman). -

Andtheirassistancetorussiainthe

Panslawizm – wczoraj, dziś, jutro Borche Nikolow Uniwersytet Świętych Cyryla i Metodego w Skopje, Instytut Historii, Republika Macedonii The Balkan Slavs solidarity during the Great Eastern Crisis (1875–1878) and their assistance to Russia in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) Solidarność Słowian bałkańskich w czasie Wielkiego Kryzysu Wschodniego (1875-1878), a ich pomoc Rosji w wojnie rosyjsko-tureckiej (1877–1878) Abstrakt: Niezdolność armii Imperium Osmańskiego do stłumienia buntu w Bośni i Hercegowinie w 1875 wywołała podniecenie wśród narodów słowiańskich na calych Bałkanach. Słowiańskie narody Bałkanów dołączyły do swoich braci z Bośni i Hercegowiny w walce przeciwko Turkom. W latach Wielkiego Kryzysu Wschodniego (1875-1878) Serbia i Czarnogóra wypowiedziała wojnę Imprerium Osmańskiemu, a w Bułgarii i w Tureckiej Macedonii wybuchły liczne powstania. Narody bałkańskie wspierały się wzajemnie w walce przeciwko Imprerium, pomogły także armii rosyjskiej w czasie woj- ny rosyjsko-tureckiej (1877–1878) wysyłając wolontariuszy, jak również ubrania, żywność, leki, itp, mając nadzieję, że wielki słowiański brat z północy pomoże im wypędzić Turków z Bałkan i przynie- sie im wyzwolenie i wolność. Słowa kluczowe: Wielki Kryzys Wschodni, Imperium Osmańskie Keywords: Big Crisis East, the Ottoman Empire 91 Plight of the Christian Slav population in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the second half of the 19th century, culminated in 1975 with the uprising, which started the Great Eastern Crisis. The Inability of the Ottoman army to quickly put down the rebellion and the local population resistance, caused excite- ment amongst the Slavic people throughout the Balkans. They hoped that the time for their liberation from the Ottoman rule had come. As a result of that sit- uation, the Slavic peoples of the Balkans joined their brothers from Bosnia and Herzegovina with the fight against the Ottomans. -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Bulgaria, October 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Bulgaria, October 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: BULGARIA October 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Bulgaria (Republika Bŭlgariya). Short Form: Bulgaria. Term for Citizens(s): Bulgarian(s). Capital: Sofia. Click to Enlarge Image Other Major Cities (in order of population): Plovdiv, Varna, Burgas, Ruse, Stara Zagora, Pleven, and Sliven. Independence: Bulgaria recognizes its independence day as September 22, 1908, when the Kingdom of Bulgaria declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire. Public Holidays: Bulgaria celebrates the following national holidays: New Year’s (January 1); National Day (March 3); Orthodox Easter (variable date in April or early May); Labor Day (May 1); St. George’s Day or Army Day (May 6); Education Day (May 24); Unification Day (September 6); Independence Day (September 22); Leaders of the Bulgarian Revival Day (November 1); and Christmas (December 24–26). Flag: The flag of Bulgaria has three equal horizontal stripes of white (top), green, and red. Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early Settlement and Empire: According to archaeologists, present-day Bulgaria first attracted human settlement as early as the Neolithic Age, about 5000 B.C. The first known civilization in the region was that of the Thracians, whose culture reached a peak in the sixth century B.C. Because of disunity, in the ensuing centuries Thracian territory was occupied successively by the Greeks, Persians, Macedonians, and Romans. A Thracian kingdom still existed under the Roman Empire until the first century A.D., when Thrace was incorporated into the empire, and Serditsa was established as a trading center on the site of the modern Bulgarian capital, Sofia. -

Flotilla Admiral Georgi Penev Deputy Commander of The

FLOTILLA ADMIRAL GEORGI PENEV DEPUTY COMMANDER OF THE BULGARIAN NAVY Flotilla Admiral Georgi Penev Penev, Bulgarian Navy is a native of Provadia, Bulgaria, and was born on 19 August 1969. In 1989, he graduated from the Secondary Polytechnic School in Provadia, Bulgaria. Flotilla Admiral Penev graduated the Bulgarian Naval Academy in Varna where he got a Master Degree of Science in Navigation (1994). He was commissioned as Navigation Officer from the Bulgarian Naval Academy on August 1994. From 1995 to 1997, he served as Anti-submarine Warfare Officer onboard of KONI class frigate BGS SMELI in Varna Naval Base. His next seagoing assignment was Executive Officer of the KONI class frigate BGS SMELI from 1997 to 2003. In 2003, Flotilla Admiral Penev was selected to attend the Rakovski National Defence Academy in Sofia, and graduated in 2005. After his graduation, Flotilla Admiral Penev was appointed as Commanding Officer of the KONI class frigate BGS SMELI from 2005 to 2007. His next appointment was as Chief of Staff of the First Patrol Frigate and Corvettes Squadron in Varna Naval Base from 2007 to 2011. In 2011, Flotilla Admiral Penev was appointed as Squadron Commander of the First Patrol Frigate and Corvettes Squadron in Varna Naval Base. In 2013, Flotilla Admiral Penev reported as a student to the Rakovski National Defence College in Sofia and graduated in 2014. In 2014, Flotilla Admiral Penev was appointed as Chief of Staff in Bulgarian Naval Base, and in 2016 he received an assignment in the Bulgarian Navy Headquarters as Chief of Staff. In 2018 he assumed his current position as a Deputy Commander of the Bulgarian Navy. -

CEE Top 500 the Ranking - Economic Outlook Analysis CEE Top 500

3 6 15 35 Editorial CEE Top 500 The Ranking - Economic Outlook Analysis CEE Top 500 RANKING August 2016 COFACE CEE TOP 500 COMPANIES THE COFACE PUBLICATIONS by Coface Central Europe he year 2015 brought a The CEE Top 500 ranks the 500 biggest Favorable business conditions extended good mix of conditions for companies in the region by turnover. into 2016. The forecast for the CEE region Central and Eastern Europe. These top players increased their turnover in 2016 is nearly on the same level as Average GDP growth for by 4.2% to nearly 593 billion EUR and 2015 with an estimated average growth the CEE region was 3.3% enlarged their staff by 0.5%. Overall 4.3% rate of 3.0%. A further improvement Tin 2015, after 2.6% in 2014. Economies of the total labor force in the region is in the labor market and growing benefited from rising domestic demand. employed by the companies of the CEE confidence will strengthen household This included both, growing private Top 500 which has a positive effect consumption as the main growth driver consumption, supported by declining on unemployment rates. The ongoing of the CEE economies. The contribution unemployment and growing wages, upward trend was also recorded by of investments will not be as high as and increasing investments in most the majority of the sectors in the CEE last year due to a slow start of new EU economies. Important support came Top 500. Twelve out of thirteen sectors co-financed projects weakening the from EU funds which CEE countries increased their turnover compared to the expansion of the construction sector were efficient users of in the final year previous year. -

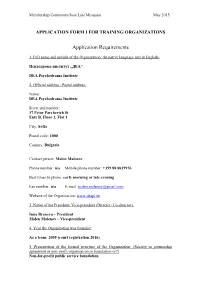

Application Requirements

Membership Committee/Jose Luis Mesquita May 2015 May 2015 APPLICATION FORM I FOR TRAINING ORGANIZATIONS Application Requirements 1. Full name and initials of the Organization: (In native language and in English) Психодрама институт „ДЕА“ DEA Psychodrama Institute 2. Official address / Postal address: Name: DEA Psychodrama Institute Street and number: 37 Petar Parchevich St Entr B, Floor 1, Flat 1 City: Sofia Postal code: 1000 Country: Bulgaria Contact person: Malen Malenov Phone number: n/a Mobile phone number: +359 88 8835976 Best times to phone: early morning or late evening Fax number: n/a E-mail: [email protected] Website of the Organization: www.deapi.eu 3. Name of the President/ Vice-president (Director/ Co-director): Inna Braneva – President Malen Malenov – Vice-president 4. Year the Organization was founded: As a team: 2009 (court registration 2016) 5. Presentation of the formal structure of the Organization: (Society or partnership agreement or non-profit organisation or foundation or?) Non-for-profit public service foundation Membership Committee/Jose Luis Mesquita May 2015 May 2015 • The primary governing body of the Foundation is its Council of Founding Members (at present – all members). • The Executive body of the Foundation consists of its President and Vice- president who are elected for a 3-year term of service. • The foundation has several committees, corresponding to its main activities: Training Curriculum committee, Outreach and PR, Financial, Library and Archives, Theoretical and Research, Networking, Control Committee. 6. History of the Organization (1/2- 1 PAGE) D.E.A. Psychodrama Institute is the union of 8 Bulgarian Psychodrama trainers and practitioners with diverse backgrounds and experience in the field of mental health, psychotherapy, academic teaching and research, social arts and related fields. -

Organisations - Bulgaria

Organisations - Bulgaria http://www.herein-system.eu/print/194 Published on HEREIN System (http://www.herein-system.eu) Home > Organisations - Bulgaria Organisations - Bulgaria Country: Bulgaria Hide all 1.1.A Overall responsibility for heritage situated in the government structure. 1.1.A Where is overall responsibility for heritage situated in the government structure? Is it by itself, or combined with other areas? Ministry's name: Ministry of Culture Overall responsibility: Overall responsibility Ministerial remit: Cultural heritage Culture Heritage 1.1.B Competent government authorities and organisations with legal responsibilities for heritage policy and management. Name of organisation: National Institute for Immovable Cultural Heritage Address: 7, Lachezar Stantchev str. Post code: 1113 City: Sofia Country: Bulgaria Website: www.ninkn.bg E-mail: [email protected] Approx. number of staff: 49.00 No. of offices: 1 Organisation type: Agency with legal responsibilities Governmental agency Approach Integrated approach Main responsibility: Yes Heritage management: Designation Permits Site monitoring Spatial planning Policy and guidance: Advice to governments/ministers Advice to owners 1 of 31 04/05/15 11:29 Organisations - Bulgaria http://www.herein-system.eu/print/194 Advice to professionals Legislation Support to the sector Research: Documentation Field recording (photogrammetry..) Inventories Post-excavation analysis Ownership and/or management No (maintenance/visitor access) of heritage properties: Learning and communication: Communication -

HERALDS of the GYMNASTIC CLUBS “YUNAK” up to the BEGINNING of the 20TH CENTURY (Research Note)

178Activities in Physical Education and Sport 2014, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 178-183 HERALDS OF THE GYMNASTIC CLUBS “YUNAK” UP TO THE BEGINNING OF THE 20TH CENTURY (Research note) Sergei Radoev South-West University “Neofit Rilski” Blagoevgrad Faculty “Public Health and Sport” Department “Sport and Kinezitherapy”, Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria Abstract In the present work are revealed the prerequisites and the reasons for the appearance of the gymnastic movement in Bulgaria. The accent is put on the fact that the gymnastic exercises are closely connected with the physical preparation of the revolutionaries in the Balkans and have great significance for the resistance and readiness to fight in the crude conditions of revolutionary life. Underlined is the significance of Vassil Levski for the organization of the “gymnastic groups”. Presented are the historic data about the first gymnastic club “Yunak” in Sofia (1895). By one of the Swiss teachers who came to Bulgaria to teach gymnastics, Bulgaria becomes co-founder of the Olympic Games. Described are the reasons for the unification of the different clubs into Union of the Bulgarian gymnastic clubs “Yunak” in Sofia in 1898. Described are the 1st and the 2nd congresses (1898 – 1900) – Sofia, as well as the 1st national meeting – 1900 in Varna, upbringing its members in love to the Homeland. Keywords: physical education, physical development of students, classes in gymnastics, physical exercises, International Gymnastics Federation, Olympic games INTRODUCTION has been preliminary training on horses – getting on and About the history of the physical education and off static or moving horse which is earlier announced by the gymnastics mainly write: Tsonkov (Цонков) (1968); Flavii Vegetsii. -

Relics of the Bulgarian National Epic

PAISStt OF HILENDAR: FOUNDER OF THE NATIONAL IDEOLOGY In modern historiography the first centuries of the of the respectful image of Mediaeval Bulgaria. In Sremski Ottoman rule of Bulgarian lands are determined as Late Karlovci, one of the most active literary centres of the Middle Ages. The time from the beginning of the 18th time, Paissi read the book of Dubrovnik Abbot Mavro century to the 1877-1878 Russo-Turkish War is called Orbini "The Realm of the Slavs" in which he discovered Bulgarian National Revival. If the National Revival period considerable evidence about the Bulgarians' past. for Northern Bulgaria and the Sofia Region continued by In 1762 he completed "Slav-Bulgarian History, about 1878, for Eastern Rumelia it was by 1885 and for the People and the Kings, the Bulgarian Saints and All Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace by 1912-1913. Bulgarian Activities and Events". In 83 hand-written The National Revival in the Bulgarian lands witnessed pages the inspired Hilendar Monk interpreted using considerable economic progress. The Bulgarian were romantic and heightened tone the grandour of increasingly getting rid of their mediaeval restricted out- Mediaeval Bulgaria, the victory of the Bulgarian army look and helplessness and were gradually getting aware over Byzantium, the impressive bravery and manliness of as people, aspiring towards economic and cultural the Bulgarians, the historic mission of the Cyril and progress. Hilendar monk Paissii became a mouthpiece of Methodius brothers and other eloquent facts, worthy to these changes in the national self-awareness. He was be remembers and respected by the successors. Already the first to perceive the beginning of the new time and in the forward this noted Bulgarian appealed with gen- the need of formulating verbally the maturing historical uine sincerity towards his compatriots to love and keep prospects and tasks before the Bulgarian people. -

TANZIMAT in the PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) and LOCAL COUNCILS in the OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840S to 1860S)

TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s) Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde einer Doktorin der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel von ANNA VAKALIS aus Thessaloniki, Griechenland Basel, 2019 Buchbinderei Bommer GmbH, Basel Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Dokumentenserver der Universität Basel edoc.unibas.ch ANNA VAKALIS, ‘TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s)’ Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel, auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Maurus Reinkowski und Assoc. Prof. Dr. Yonca Köksal (Koç University, Istanbul). Basel, den 05/05/2017 Der Dekan Prof. Dr. Thomas Grob 2 ANNA VAKALIS, ‘TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s)’ TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………..…….…….….7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………...………..………8-9 NOTES ON PLACES……………………………………………………….……..….10 INTRODUCTION -Rethinking the Tanzimat........................................................................................................11-19 -Ottoman Province(s) in the Balkans………………………………..…….………...19-25 -Agency in Ottoman Society................…..............................................................................25-35 CHAPTER 1: THE STATE SETTING THE STAGE: Local Councils -

BULGARIAN REVIVAL INTELLIGENTSIA Natural

BULGARIAN REVIVAL INTELLIGENTSIA Natural Philosophy System of Dr. Petar Beron Petar Beron was born at year 1800 in the town Kotel, “a miniature of Nuremberg”, in a rich family of handcrafts and merchants. In Kotel he received his primary education at the cell school of Stoiko Vladislavov and Raino Popovich. He went further to Bucharest where he entered the school of Greek educator Konstantin Vardalach. The latter, a famous for his time pedagogue and encyclopedist, had influenced a lot for the formation of Beron as scientist and philosopher. In 1824 Beron is compelled to leave Bucharest, because he participated in a “Greek plot”, and goes to Brashov, another Rumanian town, where he compiled “The Fish Primer”. This book was fundamental for the Reformation in Bulgaria and an achievement for the young scholar. In 1825 Beron enrolled as a student in Heidelberg University, Germany, where he proceeded philosophy until two years later when he transferred to Munich to study medicine. On the 9 July 1831, after successfully defending a doctoral dissertation, Beron was promoted Doctor in Medicine. Dissertation was in Latin and concerned an operation technique in Obstetrics and Gynecology. The young physician worked in Bucharest and Craiova, but after several years of general practice he quit his job and started merchandise. After fifteen years he made a fortune and went to Paris where he lived as a renter. Here he started a real scientific career. His scope was to entail all the human knowledge by that time and to make a natural philosophy evaluation by creating a new “Panepisteme”. His encyclopedic skills were remarkable. -

Migration of Roma Population to Italy and Spain

CHAPTER – ROMA MIGRANTS FROM BULGARIA AND ROMANIA. MIGRATION PATTERNS AND INTEGRATION IN ITALY AND SPAIN 2012 COMPARATIVE REPORT EU INCLUSIVE SUMMARY Immigration trends in Italy and Spain – an overview ........................................................................... 2 Roma migration toward Italy and Spain ............................................................................................. 2 Home country perspective: Roma migrants from Romania and Bulgaria .......................................... 4 Selectivity of Roma migration ....................................................................................................... 7 Patterns of Roma migration ........................................................................................................ 10 Transnationalism of Romanian and Bulgarian Roma in Italy and Spain ......................................... 16 Discussion: Roma inclusion and the challenges which lie ahead...................................................... 18 References ....................................................................................................................................... 19 Immigration trends in Italy and Spain – an overview Italy and Spain, traditionally known as countries of emigration, became by the end of the 1970s countries of immigration (Bonifazi 2000). During the recent decades, these countries have received growing immigrant flows, mostly originating from other European countries, especial from Central and Eastern European countries after the