Western Orissa Brandter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement Brochure 2018-19

PLACEMENT BROCHURE 2018-19 Government College of Engineering Kalahandi, Bhawanipatna (A Constituent College of BPUT, Odisha) (http://gcekbpatna.ac.in/) • VISION & MISSION • STUDENT ACTIVITIES • GCEK AT A GLANCE • CLUBS • MESSAGE FROM THE PRINCIPAL • TRAINING AND PLACEMENT CELL • MESSAGE FROM THE PIC (T&P CELL) • PLACEMENT TEAM • INFRASTRUCTURE • HOW TO REACH @ GCEK • WHY RECRUIT US • T&P ACTIVITIES • DEPARTMENT DEMOGRAPHICS • OUR ALUMNI • COMPUTER SCIENCE & ENGINEERING • ACHIEVEMENTS • ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING • TRAINING AND INTERNSHIPS • MECHANICAL ENGINEERING • IN AND AROUND GCEK • CIVIL ENGINEERING • STUDENT COORDINATORS • BASIC SCIENCE & HUMANITIES • CONTACT US VISION MISSION • To produce high profile technical graduates with • To be an academic institution of excellence striving innovative thinking and technical skills to meet the persistently for advancement of technical education challenges of the society. and research in service to mankind. • To foster, promote and sustain scientific research in emerging fields of technology. • To establish interactions with leading technological institutions, research centres and industries of national and international repute. • To induct in each member of GCEK , the spirit of humanity , diligence and dedication to work for betterment of humankind. Government College of Engineering, Kalahandi was established in the year 2009 by an act of Govt. of Odisha and stands a humble spectacle where tradition meets modernisation, aspiration meets inspiration, where our aim is to keep scaling new heights. Functioning as a constituent college of BPUT, Odisha, the college offers 4 years Under Graduate B.Tech degree programme in Civil Engineering, Computer Science &Engineering, Electrical Engineering and Mechanical Engineering & Masters degree in Thermal Engineering and Power System Engineering. For structural enhancing the institute has been successful in keeping itself up to the standards by surpassing the expectation in producing a brand of engineers capable of adapting all over the world. -

District Irrigation Plan of Kalahandi District, Odisha

District Irrigation Plan of Kalahandi, Odisha DISTRICT IRRIGATION PLAN OF KALAHANDI DISTRICT, ODISHA i District Irrigation Plan of Kalahandi, Odisha Prepared by: District Level Implementation Committee (DLIC), Kalahandi, Odisha Technical Support by: ICAR-Indian Institute of Soil and Water Conservation (IISWC), Research Centre, Sunabeda, Post Box-12, Koraput, Odisha Phone: 06853-220125; Fax: 06853-220124 E-mail: [email protected] For more information please contact: Collector & District Magistrate Bhawanipatna :766001 District : Kalahandi Phone : 06670-230201 Fax : 06670-230303 Email : [email protected] ii District Irrigation Plan of Kalahandi, Odisha FOREWORD Kalahandi district is the seventh largest district in the state and has spread about 7920 sq. kms area. The district is comes under the KBK region which is considered as the underdeveloped region of India. The SC/ST population of the district is around 46.31% of the total district population. More than 90% of the inhabitants are rural based and depends on agriculture for their livelihood. But the literacy rate of the Kalahandi districts is about 59.62% which is quite higher than the neighboring districts. The district receives good amount of rainfall which ranges from 1111 to 2712 mm. The Net Sown Area (NSA) of the districts is 31.72% to the total geographical area(TGA) of the district and area under irrigation is 66.21 % of the NSA. Though the larger area of the district is under irrigation, un-equal development of irrigation facility led to inequality between the blocks interns overall development. The district has good forest cover of about 49.22% of the TGA of the district. -

Archaelogical Remains in Kachhimdola & Deundi

ISSN No. 2231-0045 VOL.II* ISSUE-IV*MAY-2014 Periodic Research Archaelogical Remains in Kachhimdola & Deundi Village of Kalahandi Abstract The history of modern Kalahandi goes back to the primitive period where a well-civilized, urbanized and cultured people inhabited on this land mass around 2000 years ago. The world's largest celt of Stone Age and the largest cemetery of the megalithic age have been discovered in Kalahandi – this shows the region had cradle of civilization since the pre-historic era. Asurgarh near Narla in Kalahandi was one of the oldest civilization in Odisha. Some other historical forts in the region includes Budhigarh (ancient period), Amthagarh (ancient period), Belkhandi (ancient to medieval period) and Dadpur-deypur (medieval period). In ancient history this kingdom was serving as salt route to link between ancient Kalinga and South Kosala. This land was unconquered by the great Ashoka, who fought the great Kalinga war (Ashokan record). Predeep Kumar Behera Temple of Goddess Stambeswari at Asurgarh, built during 500 AD, is a perfect example where the first brick Temple in Eastern India HOD, PG was built. Sanskritization in Odisha was first started from Dept of History, Kalahandi, Koraput region in ancient Mahakantara region. Earliest flat- Sambalpur University roofed stone temple of Odisha was built at Mohangiri in Kalahandi during 600 AD. Temple architecture achieved perfection at Belkhandi in Kalahandi. The distribution and occurrence of precious and semi- precious gemstones and other commercial commodities of Kalahandi region have found place in accounts of Panini in 5th century BC, Kautilya in 3rd century BC, Ptolemy in 2nd century AD, Wuang Chuang in 7th century AD and Travenier in 19th century AD. -

Annotated List of Publications of Dr Paul Yule

Dr habil Paul A. Yule, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, [email protected] 10/14/2020 Sprachen und Kulturen des Vorderen Orients - Semitistik Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Schulgasse 2 D-69117 Heidelberg Email: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7517-5839 ANNOTATED LIST OF PUBLICATIONS OF DR PAUL A. YULE I books West Asia, Arabia, Ethiopia 1‒4 I articles, reviews, internet, Oman, Yemen, Ethiopia 4‒25 II books & articles South Asia 25‒31 III book & articles Aegean 31‒33 IV other thematic areas 33‒34 V lectures 35‒43 VI editing, symposia, posters, exhibitions, television, radio, translation 43‒46 I. West Asia, Arabia, East Africa A. Books 1. N. al-Jahwari – P. Yule – Kh. Douglas – B. Pracejus – M. al-Balushi – N. al-Hinai – Y. al- Rahi – A. Tigani al-Mahi, The Early Iron Age metal hoard from the Al Khawd area (Sultan Qaboos University) Sultanate of Oman, under evaluation. Report of a hoard of copper-base Early Iron Age artefacts which came to light during landscaping on the SQU campus. The classification of metallic artefacts is updated. 2. tarikh al-yaman al-qadim ḥmyr / Himyar/Late Antique Yemen, Aichwald 2019g, ISBN 978- 3-929290-36-3 Enlarged and corrected Arabic-English edition of the German-English book published in 2007. 3. Himyar Spätantike im Jemen, Beiheft/Late antique Yemen, Beiheft / Supplement, Aichwald 2019f, ISBN 978-3-929290-41-7 This bilingual pamphlet updates the book of 2007 regarding Himyar. 4. P. Yule ‒ G. Gernez (eds.), Early Iron Age metal-working workshop in the Empty Quarter, Sultanate of Oman, waršat taṣnīʿ- al maʿādin fī al-ʿaṣr al-ḥadīdī al-mubakkir, fī ar-Rubʿ al- Ḫālī, muqāṭaʿat aẓ-Ẓāhiira aalṭanat ʿmmān taḥrīr: Būl ʾA. -

2011-Dshb-Kalahandi.Pdf

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA DISTRICT STATISTICAL HANDBOOK KALAHANDI 2011 DISTRICT PLANNING AND MONITORING UNIT KALAHANDI ( Price : Rs.25.00 ) CONTENTS Table No. SUBJECT PAGE ( 1 ) ( 2 ) ( 3 ) Socio-Economic Profile : Kalahandi … 1 Administrative set up … 4 I POSITION OF DISTRICT IN THE STATE 1.01 Geographical Area … 5 District wise Population with Rural & Urban and their proportion of 1.02 … 6 Odisha. District-wise SC & ST Population with percentage to total population of 1.03 … 8 Odisha. 1.04 Population by Sex, Density & Growth rate … 10 1.05 District wise sex ratio among all category, SC & ST by residence of Odisha. … 11 1.06 District wise Literacy rate, 2011 Census … 12 Child population in the age Group 0-6 in different district of Odisha. 1.07 … 13 II AREA AND POPULATION Geographical Area, Households and Number of Census Villages in different 2.01 … 14 Blocks and ULBs of the District. 2.02 Classification of workers (Main+ Marginal) … 15 2.03 Total workers and work participation by residence … 17 III CLIMATE 3.01 Month wise Actual Rainfall in different Rain gauge Stations in the District. … 18 3.02 Month wise Temperature and Relative Humidity of the district. … 20 IV AGRICULTURE 4.01 Block wise Land Utilisation pattern of the district. … 21 Season wise Estimated Area, Yield rate and Production of Paddy in 4.02 … 23 different Blocks and ULBs of the district. Estimated Area, Yield rate and Production of different Major crops in the 4.03 … 25 district. 4.04 Source- wise Irrigation Potential Created in different Blocks of the district … 26 Achievement of Pani Panchayat programme of different Blocks of the 4.05 … 27 district 4.06 Consumption of Chemical Fertiliser in different Blocks of the district. -

Early Historic Sites in Orissa©

Paul Yule (ed.), Early Historic Sites in Orissa Early Historic Sites in Orissa© Paul Yule with contributions by others Introduction 2–4 Sources and State of Research 4–5 Geographical and Chronological Scope 5 Purpose and Historical Hypothesis 6–7 Sites Surveyed 8–23 Excavated Sites 24–32 Finds 33–36 Synthesis 37–48 Excursis: C. Meyer, Ground Penetrating Radar Investigation in Sisupalgarh, 2005 49–54 Sources cited 55–61 Text figures 62–96 appended digital images and a list of contained images. Read first "0000 photo CD" Paul Yule (ed.), Early Historic Sites in Orissa Introduction While art historians have long celebrated the intellectual and artistic achievement of the medieval temple art of Orissa, quantitatively and qualitatively its archaeology trails behind that of most of South Asia. Until recently archaeology has remained a matter essentially of local interest. One can point to a variety of causes including the general poverty of the area, until recently a lack of basic infrastructure, as well as the scarcity of routined and trained field professionals. Despite rare informational stepping stones, archaeologically early historic western Orissa and the adjacent Chhattisgarh region are best described as archaeological terra incognita. Moreover, other areas of Orissa such as southern Koraput and parts of Malkangiri are even less well explored and are relatively inaccessible to archaeologists (Fig. 1). A main task below is to make such sources available, build on this documentation, and catalyse future work. The dearth of scholarly attention to Orissa has nothing to do with its great archaeological promise. Luxury is being the first to discuss major structures and sites only recently described, drawn, or photographed. -

PCA CDB-2126-F-Census.Xlsx

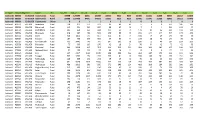

DT Name Town/VillageLevel Name TRU No_HH TOT_P TOT_M TOT_F P_06 M_06 F_06 P_SC M_SC F_SC P_ST M_ST F_ST Kalahandi 000000 CD BLOCK Golamunda Total 33998 129499 64917 64582 18651 9512 9139 22480 11141 11339 32655 16212 16443 Kalahandi 000000 CD BLOCK Golamunda Rural 33998 129499 64917 64582 18651 9512 9139 22480 11141 11339 32655 16212 16443 Kalahandi 000000 CD BLOCK Golamunda Urban 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Kalahandi 423579 VILLAGE Jayantpur Rural 120 410 207 203 86 43 43 6 6 0 379 186 193 Kalahandi 423580 VILLAGE Betrajpali Rural 115 431 222 209 68 37 31 7 3 4 212 115 97 Kalahandi 423581 VILLAGE Kodobhata Rural 203 868 424 444 133 63 70 179 83 96 280 142 138 Kalahandi 423582 VILLAGE Bhatipada Rural 248 987 482 505 176 86 90 291 144 147 345 173 172 Kalahandi 423583 VILLAGE Bordi Rural 360 1402 735 667 161 85 76 108 59 49 196 98 98 Kalahandi 423584 VILLAGE Kuhura Rural 187 735 376 359 97 53 44 133 58 75 140 78 62 Kalahandi 423585 VILLAGE Kendumundi Rural 362 1441 741 700 197 106 91 100 51 49 214 114 100 Kalahandi 423586 VILLAGE Balipadar Rural 79 339 169 170 42 18 24 76 34 42 75 42 33 Kalahandi 423587 VILLAGE Kantamal Rural 403 1568 807 761 223 111 112 203 102 101 275 140 135 Kalahandi 423636 VILLAGE Mahendrapur Rural 52 200 103 97 30 16 14 0 0 0 174 91 83 Kalahandi 423637 VILLAGE Lanji Rural 537 2207 1092 1115 318 154 164 362 187 175 260 111 149 Kalahandi 423638 VILLAGE Sinapali Rural 395 1494 750 744 159 81 78 390 189 201 265 131 134 Kalahandi 423639 VILLAGE Kulihapada Rural 128 488 256 232 69 39 30 76 40 36 361 187 174 Kalahandi 423640 -

District Industrial Potentiality Survey Report Kalahandi 2019-20

District Industrial Potentiality Survey Report Kalahandi 2019-20 MSME Development Institute Vikash Sadan, College Square, Cuttack Odisha-753003 Telephone: 0671- 2950011, Fax: 2201006 E. Mail: [email protected] Website: www.msmedicuttack.gov.in i Contents Sl. No. Chapters Subject Page No. 1. Chapter-I Introduction 1-2 2. Chapter-II Executive Summary 3-4 3. Chapter-III District at a Glance 5-7 4. Chapter-IV District Profile 8-11 5. Chapter-V Resource Analysis 12-29 6. Chapter-VI Infrastructure Available for Industrial 30-38 Development 7. Chapter-VII Present Industrial Structure 39-45 8. Chapter-VIII Prospects of Industrial Development 46-49 9. Chapter- IX Plan of Action for promoting Industrial 50-52 Development in the District 10. Chapter- X Steps to set up MSMEs 53-54 11. Chapter- XI Conclusion 55 12. Annexure Policies of the State Government 56-71 ii List of Acronyms AHVS Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Services APEDA Agricultural & Processed Food Products Export Development Authority APICOL Agricultural Promotion & Investment Corporation of Odisha Limited CD Credit Deposit CFC Common Facility Centre CHC Community Health Centre DEPM Directorate of Export Promotion & Marketing DES Directorate of Economics & Statistics DIC District Industries Centre DTET Directorate of Technical Education & Training EDP Entrepreneurship Development Programme ESDP Entrepreneurship Skill Development Programme FIEO Federation of Indian Export Organizations Ha Hectare IDCO Odisha Industrial Infrastructure Development Corporation IMC Industrial Motivation Campaign IPICOL Industrial Promotion & Investment Corporation of Odisha Limited IPR Intellectual Property Rights IT Information Technology KVIB Khadi & Village Industries Board KVIC Khadi & Village Industries Commission MHU Mobile Health Unit MPEDA Marine Products Export Development Authority MT Metric Tonne MARKFED Odisha State Co-Operative Marketing Federation Ltd. -

M.I.Division Kalahandi.Xlsx

STATUS OF IRRIGATION SUPPLIED DURING KHARIFF AS ON SEPTEMBER 2015 IN KALAHANDI DISTRICT Length of canal system in Ayacut in Ha. Reason for less/ Km excess of ayacut Sl Name of Ayacut Name of Block Name of MIP Actual length in Actual irrigated/ Reason No. District Design Designed irrigated upto which water Potential for not reaching length Ayacut 30th Sept' supplied Created tail end 2015 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Artal MIP 2.21 1.75 81.00 81.00 65.00 Shortage of Water 2 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Ashasagar MIP 2.50 2.50 121.00 121.00 50.00 Shortage of Water 3 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Balipati MIP 1.00 1.00 40.00 40.00 40.00 Full Ayacut 4 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Devisagar MIP 4.60 4.05 132.00 132.00 95.00 Shortage of Water 5 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Haldi MIP 1.10 0.85 49.00 49.00 40.00 Shortage of Water 6 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Jamunasagar MIP 4.31 3.80 180.00 180.00 160.00 Shortage of Water 7 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Karlapada MIP 0.83 0.83 40.00 40.00 40.00 Full Ayacut 8 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Kasakendu MIP 0.70 0.50 40.00 40.00 30.00 Shortage of Water Kharsanpur MIP 9 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna 0.55 0.40 49.00 49.00 35.00 Shortage of Water (D/W) 10 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Kusumsila MIP 0.98 0.98 114.00 114.00 90.00 Shortage of Water Mahijore MIP 11 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna 1.08 0.85 67.00 67.00 40.00 Shortage of Water (D/W) Medinipur MIP 12 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna 5.41 4.25 396.00 396.00 240.00 Shortage of Water (D/W) 13 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna Pipalnalla MIP 14.00 13.20 809.00 809.00 750.00 Shortage of Water 14 Kalahandi Bhawanipatna -

District Statistical Handbook Kalahandi 2015

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK KALAHANDI 2015 DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS, ODISHA GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA DISTRICT STATISTICAL HANDBOOK KALAHANDI 2015 DISTRICT PLANNING AND MONITORING UNIT KALAHANDI ( Price : Rs.25.00 ) CONTENTS Table No. SUBJECT PAGE ( 1 ) ( 2 ) ( 3 ) Socio-Economic Profile : Kalahandi … 1 Administrative set up … 4 I. POSITION OF DISTRICT IN THE STATE 1.01 Geographical Area … 5 1.02 District-wise Population with SC & ST and their percentage to total … 6 population of Odisha as per 2011 Census 1.03 Population by Sex, Density & Growth rate … 7 1.04 District-wise sex ratio among all category, SC & ST by residence of … 8 Odisha. 1.05 District-wise Population by Religion as per 2011 Census … 9 1.06 District-wise Literacy rate, 2011 Census … 10 1.07 Child population in the age Group 0-6 in different districts of Odisha … 11 1.08 Age-wise Population with Rural and Urban of the district … 12 1.09 Decadal Variation in Population since 1901 of the district … 13 1.10 Disabled Population by type of Disability as per 2011 Census … 14 II. AREA AND POPULATION 2.01 Geographical Area, Households and Number of Census Villages in … 15 different Blocks and ULBs of the district. 2.02 Total Population, SC and ST Population by Sex in different Blocks … 16 and Urban areas of the district 2.03 Total number of Main Workers, Marginal Workers and Non- … 18 Workers by Sex in different Blocks and Urban areas of the district. 2.04 Classification of Workers ( Main + Marginal ) in different Blocks … 20 and Urban areas of the district. -

Early Historic Cultures of Orissa

Orissa Review * April - 2007 Early Historic Cultures of Orissa Dr. Balaram Tripathy The Early Historic cultures of Orissa, unlike other conducted on some representative types of states, has not yet been considered in a holistic pottery found at the sites in hinterland Orissa. viewpoint, and hence an effort is made here to Orissa, in ancient times known as Kalinga, unravel certain noteworthy aspects pertaining to was a far-flung cultural unity, spread over the vast urbanisation and trade mechanism, including regions encompassing territories from the Ganges overseas acquaintances. Emphasis has been laid to the Godavari and sometimes upto the Krishna on issues like trade routes and expansion of river. The ancient texts such as Bhagavati Sutra, Buddhist perception into the upland/hinterland a Jaina text mentions the name of Kalinga Orissa, at least in material culture like pottery Janapada in the 6th century B.C. Of course, in (Knobbed Ware). Classification of major centres the Anguttara Nikaya, a Buddhist text, Kalinga in terms of function and production has been Janapada doesn't find a place (as quoted in discussed here to have a clear understanding of Rayachaudhury 1938). However, the recent hitherto unknown features in early Indian history archaeological explorations and excavations have in general and of Orissa in particular. Direct and revealed interesting data pertaining to urbanization indirect contacts of states/centres with each other and city formation during the Early Historic period have been analyzed and discussed. in Orissa. If we will consider its chronology and Archaeological objects such as pottery and stages of formation, we may conclude that supplementary antiquities as also the ecological throughout the early historic period, Orissa aspects have been taken into consideration to flourished under several names and under several infer the function of urban centres. -

The Kandha Revolution in Kalahandi

Orissa Review August - 2007 The Kandha Revolution in Kalahandi Dina Krishna Joshi, Sasmita Mund and Dr. Mihir Prasad Mishra Numerically, the second most important faithfully to their rulers. They offered their valuable Scheduled tribe of Kalahandi is the Khond, Kond services at the time of freedom movement. To or Kandha. They are found everywhere in the name a few among them are Chakara Bisoyi and district and have three main divisions, viz., Kutia, Dohra Bisoyi. Their behaviour is pleasant and they Dangaria and Desia. The Kutia Kandha lives in a are extremely hospitable to guests, giving house, the floor of which is below the level of the protection to enemies if they take refuge. They ground around the house. The Dangaria Kandhas are generally kind and cheerful and are lovers of are known as Malia Kandhas. They live in high recreation. land hills. The Desia Kandhas live in the plain area with other non-tribals. Kui is the mother tongue The twenty-seventh Nagavamsi ruler of of the Kandhas but they know Oriya and speak Kalahandi ex-state was Shri Fateh Narayan Deo, with others in this language. The Kandhas are who died in 1854 and was succeeded by his son generally dark in complexion, though, among Udit Pratap Deo. During his reign the Kandhas them, some fair skinned persons are also found. of Madanpur-Rampur Zamindary rebelled for An average male Kandha is about 5 feet 4 inches sometime but was easily quelled by the skillful in height. They are slim but muscular. The females management of their affairs.