Indra Kesuma Nasution 主論文

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesia Beyond Reformasi: Necessity and the “De-Centering” of Democracy

INDONESIA BEYOND REFORMASI: NECESSITY AND THE “DE-CENTERING” OF DEMOCRACY Leonard C. Sebastian, Jonathan Chen and Adhi Priamarizki* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: TRANSITIONAL POLITICS IN INDONESIA ......................................... 2 R II. NECESSITY MAKES STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: THE GLOBAL AND DOMESTIC CONTEXT FOR DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIA .................... 7 R III. NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ................... 12 R A. What Necessity Inevitably Entailed: Changes to Defining Features of the New Order ............. 12 R 1. Military Reform: From Dual Function (Dwifungsi) to NKRI ......................... 13 R 2. Taming Golkar: From Hegemony to Political Party .......................................... 21 R 3. Decentralizing the Executive and Devolution to the Regions................................. 26 R 4. Necessary Changes and Beyond: A Reflection .31 R IV. NON NECESSITY-BASED REFORMS ............. 32 R A. After Necessity: A Political Tug of War........... 32 R 1. The Evolution of Legislative Elections ........ 33 R 2. The Introduction of Direct Presidential Elections ...................................... 44 R a. The 2004 Direct Presidential Elections . 47 R b. The 2009 Direct Presidential Elections . 48 R 3. The Emergence of Direct Local Elections ..... 50 R V. 2014: A WATERSHED ............................... 55 R * Leonard C. Sebastian is Associate Professor and Coordinator, Indonesia Pro- gramme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of In- ternational Studies, Nanyang Technological University, -

Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History

Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Emile Schwidder & Eef Vermeij (eds) Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Emile Schwidder Eef Vermeij (eds) Guide to the Asian Collections at the International Institute of Social History Stichting beheer IISG Amsterdam 2012 2012 Stichting beheer IISG, Amsterdam. Creative Commons License: The texts in this guide are licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 license. This means, everyone is free to use, share, or remix the pages so licensed, under certain conditions. The conditions are: you must attribute the International Institute of Social History for the used material and mention the source url. You may not use it for commercial purposes. Exceptions: All audiovisual material. Use is subjected to copyright law. Typesetting: Eef Vermeij All photos & illustrations from the Collections of IISH. Photos on front/backcover, page 6, 20, 94, 120, 92, 139, 185 by Eef Vermeij. Coverphoto: Informal labour in the streets of Bangkok (2011). Contents Introduction 7 Survey of the Asian archives and collections at the IISH 1. Persons 19 2. Organizations 93 3. Documentation Collections 171 4. Image and Sound Section 177 Index 203 Office of the Socialist Party (Lahore, Pakistan) GUIDE TO THE ASIAN COLLECTIONS AT THE IISH / 7 Introduction Which Asian collections are at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam? This guide offers a preliminary answer to that question. It presents a rough survey of all collections with a substantial Asian interest and aims to direct researchers toward historical material on Asia, both in ostensibly Asian collections and in many others. -

Tensions Among Indonesia's Security Forces Underlying the May 2019

ISSUE: 2019 No. 61 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 13 August 2019 Tensions Among Indonesia’s Security Forces Underlying the May 2019 Riots in Jakarta Made Supriatma* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • On May 21-22, riots broke out in Jakarta after the official results of the 2019 election were announced. These riots revealed a power struggle among retired generals and factional strife within the Indonesian armed forces that has developed since the 1990s. • The riots also highlighted the deep rivalry between the military and the police which had worsened in the post-Soeharto years. President Widodo is seen to favour the police taking centre-stage in upholding security while pushing the military towards a more professional role. Widodo will have to curb this police-military rivalry before it becomes a crisis for his government. • Retired generals associated with the political opposition are better organized than the retired generals within the administration, and this can become a serious cause of disturbance in Widodo’s second term. * Made Supriatma is Visiting Fellow in the Indonesia Studies Programme at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2019 No. 61 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION The Indonesian election commission announced the official results of the 2019 election in the wee hours of 21 May 2019. Supporters of the losing candidate-pair, Prabowo Subianto and Sandiaga Uno, responded to the announcement with a rally a few hours later. The rally went on peacefully until the evening but did not show any sign of dispersing after the legal time limit for holding public demonstrations had passed. -

Pengumuman-04-Cpns.Pdf

PERENCANAAN PEMBANGUNAN NASIONAL/ , KEMENTERIAN BADAN PERENCANAAN PEMBANGUNAN NASIONAL , REPUBLIK INDONESIA PENGUMUMAN NOMOR : 04/PANSEL-CASN 10812021 TENTANG HASIL SELEKSI ADMINISTRAS! SELEKSI CALON APARATUR SIPTL NEGARA (ASN) KEMENTERIAN PPN/BAPPENAS TAHUN 2021 Berdasarkan hasil keputusan Rapat Panitia Seleksi Calon Aparatur Sipil Negara (ASN) Kementerian PPN/Bappenas Tahun 2021, disampaikan beberapa hal sebagai berikut : 1. Peserta yang dinyatakan LULUS Seleksi Administrasi atau Memenuhi Syarat (MS) adalah peserta yang LULUS VERIFIKASI dokumen yang diunggah melalui aplikasi https://sscasn.bkn.oo.id sesuai kualifikasi masing-masing formasiyang dilamar. 2. Daftar peserta yang dinyatakan LULUS Seleksi Administrasi tercantum pada lampiran pengumuman ini atau dapat dilihat pada akun SSCASN masing-masing. Peserta yang LULUS dapat mengikuti tahap seleksi berikutnya, yaitu Seleksi Kompetensi Dasar (SKD) berbasis Computer Assisfed lesf (CAT). 3. Bagi peserta yang tidak tercantum dalam lampiran pengumuman ini dinyatakan TIDAK LULUS atau Tidak Memenuhi Syarat (TMS). Alasan ketidaklulusan dapat dilihat pada masing-masing akun SSCASN. 4. Peserta yang dinyatakan TIDAK LULUS SeleksiAdministrasi diberikan kesempatan memberikan pernyataan sanggahan pada masa sanggah yang berlangsung mulai tanggal 4 s.d 6 Agustus 2021 dan masa jawab sanggah oleh panitia mulai tanggal 4 s.d 13 Agustus 2021. 5. Pengumuman SeleksiAdministrasi Pasca Sanggah akan diumumkan pada tanggal 15 Agustus 2021 pada website https://rekrutmen.bappenas.oo.id/ dan/atau pada akun SSCASN -

Political Islam: the Shrinking Trend and the Future Trajectory of Islamic Political Parties in Indonesia

Political Islam: The shrinking trend and the future trajectory of Islamic political parties in Indonesia Politik Islam: Tren menurun dan masa depan partai politik Islam di Indonesia Ahmad Khoirul Umam1 & Akhmad Arif Junaidi 2 1Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, The University of Queensland, Australia 2 Faculty of Sharia and Law, State Islamic University (UIN) Walisongo, Semarang Jalan Walisongo No. 3-5, Tambakaji, Ngaliyan, Kota Semarang, Jawa Tengah Telepon: (024) 7604554 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The trend of religious conservatism in Indonesian public sector is increasing nowadays. But the trend is not followed by the rise of political ,slam‘s popularity. The Islamic political parties are precisely abandoned by their sympathizers because of some reasons. This paper tries to elaborate the reasons causing the erosion of Islamic parties‘ political legitimacy. Some fundamental problems such as inability to transform ideology into political platform, internal-factionalism, as well as the crisis of identity will be explained further. The experience from 2009 election can be used to revitalize their power and capacity for the better electability in the next 2014 election. But they seem to be unable to deal with the previous problems making the electability erosion in 2014 more potential and inevitable. Various strategies must be conducted by the parties such as consolidation, revitalizing their political communication strategy, widening political networks across various ideological and religious streams, and others. Without that, their existence would be subordinated by the secular parties to become the second class political players in this biggest Moslem country in the world. Keywords: democracy, Islam, political parties, election, electability, Indonesia Abstrak Fenomena konservatisme agama di Indonesia di sektor publik terus tumbuh. -

Dr. Krt. Rajiman Wedyodiningrat

,Milik Depdikbud Tidak Diperdagangkan DR. KRT. RAJIMAN WEDYODININGRAT: Hasil Karya dan Pengabdiannya Milik Depdikbud Tidak Diperdagangkan DR. KRT. RAJIMAN WEDYODININGRAT: Hasil Karya dan Pengabdiannya DEPARTEMEN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN RI JAKARTA 1998 DR. K.R.T. RAJIMAN WEDYODININGRAT Hasil Karya don Pengabdiannya Penulis Ors. A.T. Sugito, SH Penyunting Sutrisno Kutoyo Ors. M. Soenyoto Kortodormodjo. Hok cipta dilindungi oleh Undong-undong Diterbitkan ulang �h : Proyek Pengkojlan don Pembinaan Nilai-nilai Budayo Pusat Direktorat Sejorah don Nilai Tradisional Dlrektorat Jenderol Kebudayaan Deportemen Pendidikan don Kebudayaon Jakarta 1998 Edisi I 1982 Edisi II 1985 Edisi Ill 1998 Dicetak oleh CV. PIALAMAS PERMAI SAMBUTAN DIREKTUR JENDERAL KEBUDA Y AAN Penerbitan buku sebagai upaya untuk memperluas cakrawala budaya masyarakat patut dihargai. Pengenalan aspek-aspek kebudayaan dari berbagai daerah di Indonesia d iharapkan dapat mengikis etnosentrisme yang sempit di dalam masyarakat kita yang majemuk. Oleh karena itu. kami dengan gembira menyambut terbitnya buku hasil kegiatan Proyek Pengkajian dan Pembinaan Nilai nilai Budaya Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. Penerbitan buku ini diharapkan dapat meningkatkan pengetahuan masyarakat mengenai aneka ragam kebudayaan di Indonesia. Upaya ini menimbulkan kesalingkenalan dengan harapan akan tercapai tujuan pembinaan dan pengembangan kebudayaan nasional. Berkat kerjasama yang baik antara tim penulis dengan para pengurus proyek, buku ini dapat diselesaikan. Buku ini belum merupakan hasil suatu penelitian yang mendalam sehingga masih terdapat kekurangan-kekurangan. Diharapkan hal tersebut dapat disempurnakan pada masa yang akan datang. v vi Sebagai penutup kami sampaikan terima kasih kepada pihak yang telah menyumbang pikiran dan tenaga bagi penerbitan buku ini. Jakarta, September 1998 Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan Prof. -

RSIS COMMENTARIES RSIS Commentaries Are Intended to Provide Timely And, Where Appropriate, Policy Relevant Background and Analysis of Contemporary Developments

RSIS COMMENTARIES RSIS Commentaries are intended to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy relevant background and analysis of contemporary developments. The views of the authors are their own and do not represent the official position of the S.Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced electronically or in print with prior permission from RSIS. Due recognition must be given to the author or authors and RSIS. Please email: [email protected] or call (+65) 6790 6982 to speak to the Editor RSIS Commentaries, Yang Razali Kassim. __________________________________________________________________________________________________ No. 2/2011 dated 6 January 2011 Leadership Renewal in TNI: Fragile Steps Towards Professionalism By Iisgindarsah Synopsis The recent personnel changes in the Indonesian military have brought more officers from the 1980s generation into many strategic positions. Despite this encouraging rejuvenation of the ranks, the drive to professionalise the country’s military remains fragile. Commentary THE RECENT appointment of a new Commander-in-Chief for the Indonesian National Defence Forces (TNI) Admiral Agus Suhartono has been typically followed by a major reshuffle of the other ranks. From 17 November 2009 up to 18 October 2010, there were a total of 17 waves of personnel changes. These latest changes, however, not only placed officers from the Military Academy classes of 1976 to 1978 in charge of the TNI’s high command; they also highlighted the rapid promotion of officers from the 1980 to 1982 classes. Professionalising the Military The rapid rise of the 1980s generation officers is to overcome the shortage of high-ranking military officers to occupy top positions in TNI Headquarters and several civilian ministries. -

Soekarno Dan Kemerdekaan Republik Indonesia

SOEKARNO DAN PERJUANGAN DALAM MEWUJUDKAN KEMERDEKAAN RI (1942-1945) SKRIPSI Robby Chairil 103022027521 FAKULTAS ADAB HUMANIORA JURUSAN SEJARAH PERADABAN ISLAM UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2010 / 1431 H ABSTRAKSI Robby Chairi Perjuangan Soekarno Dalam Mewujudkan Kemerdekaan RI (1942-1945) Perjuangan Soekarno dimulaii pada saat beliau mendirika Partai Nasional Indoonesia (PNI) tahun 1927, dan dijadikannya sebagai kendaraan poliitiknya. Atas aktivitasnya di PNI yang selalu menujuu kearah kemerdekaan Indonesia, ditambah lagi dengan pemikiran dan sikapnya yang anti Kolonialliisme dan Imperialisme, dan selalu menentang selalu menentang Kapitalisme-Imperialisme. Dengan perjuangan Soekarno bersama teman-temannya pada waktu itu dan bantuan Tentara Jepang, penjajahan Belanda dapat diusir dari Indonesia. Atas bantuan Jepang mengusir Belanda dari Indonesia, maka timbulah penjajah baru di Indonesia yaitu Jepang pada tahun 1942. Kedatangan tentara Jepang ke Indonesia bermula ingin mencari minyak dan karet, dan disambut dengan gembira oleh rakyat Indonesia yang dianggap akan membantu rakyat Indonesia mewuudkan kemakmuran bagi bangsa-bangsa Asia. Bahkan, pada waktu kekuuasaan Jepang di Indonesia, Soekarno dengan tterpaksa turut serta bekerja sama dengan Jepang dan ikut ambil bagian dalam organisassi buatan Jepang yaitu, Jawa Hokokai, Pusat Tenaga Rakyyat (PUTERA), Badan Penyelidik Usaha-Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (BPUPKI), dan Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (PPKI). Terjalinnya kerjasama dengan Jepang, membawa dampak yang sangat besar baginya yaitu, Soekarno dijulukii sebagai Kolaborator dan penjahat perang, Soekarno memanfaatkan kerjasama itu dengan menciptakan suatu pergerakan menuju Indonesia merdeka. Dengan pemikiran, sikap dan ucapan Sokarno yang selalu menentang Kolonialisme, Kapitaisme, Imperialisme, dan bantuan teman seperjuangan Soekarno pada waktu itu, akhirnya dapat mendeklarasikan teks Proklamasi di rumah Soekarno, di Jalan Pengangsaan Timur No. 56, pada harri Jumat tanggal 17 Agustus 1945. -

Political Islam: the Shrinking Trend and the Future Trajectory of Islamic Political Parties in Indonesia

Political Islam: The shrinking trend and the future trajectory of Islamic political parties in Indonesia Politik Islam: Tren menurun dan masa depan partai politik Islam di Indonesia Ahmad Khoirul Umam1 & Akhmad Arif Junaidi 2 1Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, The University of Queensland, Australia 2 Faculty of Sharia and Law, State Islamic University (UIN) Walisongo, Semarang Jalan Walisongo No. 3-5, Tambakaji, Ngaliyan, Kota Semarang, Jawa Tengah Telepon: (024) 7604554 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The trend of religious conservatism in Indonesian public sector is increasing nowadays. But the trend is not followed by the rise of political Islam‟s popularity. The Islamic political parties are precisely abandoned by their sympathizers because of some reasons. This paper tries to elaborate the reasons causing the erosion of Islamic parties‟ political legitimacy. Some fundamental problems such as inability to transform ideology into political platform, internal-factionalism, as well as the crisis of identity will be explained further. The experience from 2009 election can be used to revitalize their power and capacity for the better electability in the next 2014 election. But they seem to be unable to deal with the previous problems making the electability erosion in 2014 more potential and inevitable. Various strategies must be conducted by the parties such as consolidation, revitalizing their political communication strategy, widening political networks across various ideological and religious streams, and others. Without that, their existence would be subordinated by the secular parties to become the second class political players in this biggest Moslem country in the world. Keywords: democracy, Islam, political parties, election, electability, Indonesia Abstrak Fenomena konservatisme agama di Indonesia di sektor publik terus tumbuh. -

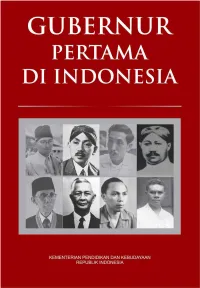

Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R

GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid (Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan) Triana Wulandari (Direktur Sejarah) NARASUMBER Suharja, Mohammad Iskandar, Mirwan Andan EDITOR Mukhlis PaEni, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi, Triana Wulandari PENULIS Andi Lili Evita, Helen, Hendi Johari, I Gusti Agung Ayu Ratih Linda Sunarti, Martin Sitompul, Raisa Kamila, Taufik Ahmad SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih Budi Harjo Sayoga, Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Rawan Kurniawan, M Abduh Husain PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-572504 2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-72-3 SAMBUTAN Direktur Sejarah Dalam sejarah perjalanan bangsa, Indonesia telah melahirkan banyak tokoh yang kiprah dan pemikirannya tetap hidup, menginspirasi dan relevan hingga kini. Mereka adalah para tokoh yang dengan gigih berjuang menegakkan kedaulatan bangsa. Kisah perjuangan mereka penting untuk dicatat dan diabadikan sebagai bahan inspirasi generasi bangsa kini, dan akan datang, agar generasi bangsa yang tumbuh kelak tidak hanya cerdas, tetapi juga berkarakter. Oleh karena itu, dalam upaya mengabadikan nilai-nilai inspiratif para tokoh pahlawan tersebut Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan menyelenggarakan kegiatan penulisan sejarah pahlawan nasional. Kisah pahlawan nasional secara umum telah banyak ditulis. Namun penulisan kisah pahlawan nasional kali ini akan menekankan peranan tokoh gubernur pertama Republik Indonesia yang menjabat pasca proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia. Para tokoh tersebut adalah Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R. Pandji Soeroso (Jawa Tengah), R. -

Evaluasi Rencana Pembangunan Jalan Lingkar Di Kota Banda Aceh

EVALUASI RENCANA PEMBANGUNAN JALAN LINGKAR DI KOTA BANDA ACEH Yustina Niken R. Hendra Jurusan Teknik Sipil Universitas Katolik Parahyangan Jln. Ciumbuleuit 94, Bandung 40141 [email protected] Abstract The population of the City of Banda Aceh in the disaster prone areas, after the tsunami disaster, are likely to increase. The development of the area and the level of population mobility in the city, especially in areas prone to tsunami, created a variety of transportation problems in the city center and its surrounding areas. Therefore, in response to these conditions, the Government plans solutions to overcome the transportation problems. One of the solutions is to construct a ring road for the City of Banda Aceh. In this study, the implementation of two different development scenarios for the ring road construction was evaluated. For the Do Something in scenario 1, the construction of the ring road will be in 2031, while for the Do Something scenario 2, the ring road will be built in 2026. The average reduction of the V/C ratio given by the Do Something scenario 1 is 9.0%, which is less than that given by the Do Something scenario 2 (9.6%). It is concluded that the Do Something scenario 2 gives better results than the Do Something scenario 1. Keywords: engineering, traffic, geometric, scenario Abstrak Jumlah penduduk Kota Banda Aceh di daerah rawan bencana, pascabencana tsunami, cenderung bertambah. Pengembangan wilayah dan tingkat mobilitas penduduk di dalam kota, terutama di daerah rawan bencana tsunami, menyebabkan berbagai permasalahan transportasi yang berfokus di pusat kota dan sekitarnya. Oleh karena itu, menanggapi kondisi ini, pemerintah merencanakan solusi untuk mengatasi permasalahan transportasi tersebut. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1. Latar Belakang Selama Pemerintahan

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1. Latar Belakang Selama pemerintahan Orde Baru, TNI dan Polri yang menyatu dalam ABRI, telah terjadi dominasi militer pada hampir di semua aspek kehidupan berbangsa dan bernegara. Militer juga difungsikan sebagai pilar penyangga kekuasaan. Konsep ini muncul sebagai dampak dari implementasi konsep dwifungsi ABRI yang telah menjelma menjadi multifungsi. Akibatnya peran ABRI dalam kehidupan bangsa telah melampaui batas-batas konvensional keberadaannya sebagai alat negara di bidang pertahanan dan keamanan. Integrasi status Polri yang berwatak sipil ke dalam tubuh ABRI dapat dikatakan sebagai pengingkaran terhadap prinsip demokrasi. Pengukuhan ABRI sebagai kekuatan sosial politik baru terjadi secara legal formal setelah keluarnya UU No. 20 Tahun 1982 tentang Ketentuan Pokok Pertahanan Keamanan Negara. Lahirnya UU ini untuk lebih memantapkan landasan hukum dwifungsi ABRI, yang sebelumnya hanya diatur dalam Ketetapan MPR. Dalam UU No. 20 Tahun 1982 ditegaskan bahwa pengaturan peran sosial politik ABRI adalah sebagai kekuatan sosial yang bertindak selaku dinamisator dan stabilisator. Hal ini sebenarnya merupakan sebuah contradiction in terminis, karena bagaimana mungkin dinamisator dan stabilisator sekaligus dipegang oleh orang yang sama. Setidak-tidaknya ada dua pasal yang mendukungnya. Pasal 26 menyebutkan, Angkatan Bersenjata mempunyai fungsi sebagai kekuatan 1 2 pertahanan keamanan dan sebagai fungsi kekuatan sosial. Pasal 28 ayat (1) menegaskan, Angkatan Bersenjata sebagai kekuatan sosial bertindak selaku dinamisator dan stabilisator yang bersama-sama kekuatan sosial lainnya memikul tugas dan tanggungjawab mengamankan dan mensukseskan perjuangan bangsa dalam mengisi kemerdekaan. Sementara itu dalam ayat (2) menyatakan, bahwa dalam melaksanakan fungsi sosial, Angkatan Bersenjata diarahkan agar secara aktif mampu meningkatkan dan memperkokoh ketahanan nasional dengan ikut serta dalam pengambilan keputusan mengenai masalah kenegaraan dan pemerintahan, serta mengembangkan Demokrasi Pancasila dan kehidupan konstitusionil berdasarkan UUD 1945.