Farah Pahlavi Interview: on Marriage to the Shah, Her Unseen Art Collection and the Future of Iran by Charles Bremner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shiraz Dissertation Full 8.2.20. Final Format

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO The Shiraz Arts Festival: Cultural Democracy, National Identity, and Revolution in Iranian Performance, 1967-1977 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In Music By Joshua Jamsheed Charney Committee in charge: Professor Anthony Davis, Co-Chair Professor Jann Pasler, Co-Chair Professor Aleck Karis Professor Babak Rahimi Professor Shahrokh Yadegari 2020 © Joshua Jamsheed Charney, 2020 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Joshua Jamsheed Charney is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ Co-chair _____________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California San Diego 2020 iii EPIGRAPH Oh my Shiraz, the nonpareil of towns – The lord look after it, and keep it from decay! Hafez iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………… iii Epigraph…………………………………………………………………………. iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………… v Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………… vii Vita………………………………………………………………………………. viii Abstract of the Dissertation……………………………………………………… ix Introduction……………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter 1: Festival Overview …………………………………………………… 17 Chapter 2: Cultural Democracy…………………………………………………. -

IN IRAN Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green Fulfillment

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF BROADCASTING IN IRAN Bigan Kimiachi A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY June 1978 © 1978 BI GAN KIMIACHI ALL RIGHTS RESERVED n iii ABSTRACT Geophysical and geopolitical pecularities of Iran have made it a land of international importance throughout recorded history, especially since its emergence in the twentieth century as a dominant power among the newly affluent oil-producing nations of the Middle East. Nearly one-fifth the size of the United States, with similar extremes of geography and climate, and a population approaching 35 million, Iran has been ruled since 1941 by His Majesty Shahanshah Aryamehr. While he has sought to restore and preserve the cultural heritage of ancient and Islamic Persia, he has also promoted the rapid westernization and modernization of Iran, including the establishment of a radio and television broadcasting system second only to that of Japan among the nations of Asia, a fact which is little known to Europeans or Americans. The purpose of this study was to amass and present a comprehensive body of knowledge concerning the development of broadcasting in Iran, as well as a review of current operations and plans for future development. A short survey of the political and spiritual history of pre-Islamic and Islamic Persia and a general survey of mass communication in Persia and Iran, especially from the Il iv advent of the telegraph is presented, so that the development of broadcasting might be seen in proper perspective and be more fully appreciated. -

US Covert Operations Toward Iran, February-November 1979

This article was downloaded by: [Tulane University] On: 05 January 2015, At: 09:36 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Middle Eastern Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fmes20 US Covert Operations toward Iran, February–November 1979: Was the CIA Trying to Overthrow the Islamic Regime? Mark Gasiorowski Published online: 01 Aug 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: Mark Gasiorowski (2015) US Covert Operations toward Iran, February–November 1979: Was the CIA Trying to Overthrow the Islamic Regime?, Middle Eastern Studies, 51:1, 115-135, DOI: 10.1080/00263206.2014.938643 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2014.938643 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Success Strategies in Emerging Iranian American Women Leaders

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 Success strategies in emerging Iranian American women leaders Sanam Minoo Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Minoo, Sanam, "Success strategies in emerging Iranian American women leaders" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 856. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/856 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology SUCCESS STRATEGIES IN EMERGING IRANIAN AMERICAN WOMEN LEADERS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership by Sanam Minoo July, 2017 Farzin Madjidi, Ed.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This dissertation, written by Sanam Minoo under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Doctoral Committee: Farzin Madjidi, Ed.D., Chairperson Lani Simpao Fraizer, Ed.D. Gabriella Miramontes, Ed.D. © Copyright by Sanam Minoo 2017 All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ -

The Death of an Emperor €“ Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi

The death of an emperor – Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and his political cancer Khoshnood, Ardavan; Khoshnood, Arvin Published in: Alexandria Journal of Medicine DOI: 10.1016/j.ajme.2015.11.002 2016 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Khoshnood, A., & Khoshnood, A. (2016). The death of an emperor – Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and his political cancer. Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 52(3), 201-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajme.2015.11.002 Total number of authors: 2 Creative Commons License: CC BY-NC-ND General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 02. -

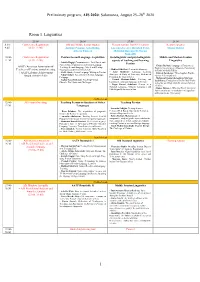

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Mohammad Reza Shah

RAHAVARD, Publishes Peer Reviewed Scholarly Articles in the field of Persian Studies: (Literature, History, Politics, Culture, Social & Economics). Submit your articles to Sholeh Shams by email: [email protected] or mail to:Rahavard 11728 Wilshire Blvd. #B607, La, CA. 90025 In 2017 EBSCO Discovery & Knowledge Services Co. providing scholars, researchers, & university libraries with credible sources of research & database, ANNOUNCED RAHAVARD A Scholarly Publication. Since then they have included articles & researches of this journal in their database available to all researchers & those interested to learn more about Iran. https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/ultimate-databases. RAHAVARD Issues 132/133 Fall 2020/Winter 2021 2853$67,163,5(6285)8785( A Quarterly Bilingual Journal of Persian Studies available (in Print & Digital) Founded by Hassan Shahbaz in Los Angeles. Shahbaz passed away on May 7th, 2006. Seventy nine issues of Rahavard, were printed during his life in diaspora. With the support & advise of Professor Ehsan Yarshater, an Advisory Commit- tee was formed & Rahavard publishing continued without interuption. INDEPENDENT: Rahavard is an independent journal entirely supported by its Subscribers dues, advertisers & contributions from its readers, & followers who constitute the elite of the Iranians living in diaspora. GOAL: To empower our young generation with the richness of their Persian Heritage, keep them informed of the accurate unbiased history of the ex- traordinary people to whom they belong, as they gain mighty wisdom from a western system that embraces them in the aftermath of the revolution & infuses them with the knowledge & ideals to inspire them. OBJECTIVE: Is to bring Rahavard to the attention & interest of the younger generation of Iranians & the global readers educated, involved & civically mobile. -

Text of the Message by Shahbanou Farah Pahlavi on the Occasion of the Passing of Mrs. Jehan Sadat 18 Tir 1400- 9 July 2021 T

Text of The Message by Shahbanou Farah Pahlavi On the Occasion of The passing of Mrs. Jehan Sadat 18 Tir 1400- 9 July 2021 The world just lost an illustrious personality of stellar qualities. I am bereaved by the loss of a dear friend who in the darkest days of our family’s life stood by our side and overwhelmed us by her kindness and friendship. Some forty years have indeed gone since President Anvar Sadat welcomed us to the ancient land of Egypt at a time no country was willing to receive us, a memory which is deeply anchored in the collective memory of Iranians. My children and I shall always treasure the memory of the cordiality and kindness that was extended to us by President and Lady Jahan Sadat and their children. In the course of these difficult years, whenever my family and I travelled to Cairo to mark the anniversary of the death of my husband, the late Shah of Iran, Jahan Sadat was there with us to lighten the distress and burden of adversities we had all endured. She was a true companion and great support by the side of her illustrious husband through the most challenging times; she took great strides for the promotion of rights and status of Egyptian women. Her name as one of the most effective advocates of gender equality and non-discrimination against women shall remain in annals. I wish to express my heartfelt condolences over the loss of this dear and inestimable friend to her children, Gamal, Lola, Noha and Jehan. May she rest in peace and her memory endure. -

ABSTRACT BIZIEFF, MICHAEL PATRICK. Jimmy Carter and the Shah

ABSTRACT BIZIEFF, MICHAEL PATRICK. Jimmy Carter and the Shah: US Foreign Relations with Iran a Year before the Fall of the Shah (Under the direction of Dr. Nancy Mitchell). This thesis investigates US relations with Iran by focusing on the Shah of Iran’s visit to Washington D.C. in November 1977, President Carter’s visit to Tehran the following December, and the US response to the protests in Qom a week after Carter’s departure. It analyses the objectives of the two visits as well as their impact. It then looks at the tragic moment when the Iranian government fired on protestors in Qom. By focusing on this two-month period, which is considered the beginning of the Iranian Revolution, this thesis deepens our understanding of the Carter administration’s policies toward Iran prior to the Iranian Revolution. © Copyright 2019 by Michael Bizieff All Rights Reserved Jimmy Carter and the Shah: US Relations with Iran a Year before the Fall of the Shah by Michael Patrick Bizieff A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2019 APPROVED BY: _______________________________ _______________________________ Dr. Nancy Mitchell Dr. Katherine Mellen Charron Committee Chair _______________________________ _______________________________ Dr. Julia Rudolph Dr. Golbarg Rekabtalaei External Member ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, and my two beautiful children, Tristan James and Thea Noël Bizieff. iii BIOGRAPHY Michael Patrick Bizieff received his undergraduate degree from North Carolina State University in Raleigh, North Carolina. -

Iran (Persia) and Aryans Part - 6

INDIA (BHARAT) - IRAN (PERSIA) AND ARYANS PART - 6 Dr. Gaurav A. Vyas This book contains the rich History of India (Bharat) and Iran (Persia) Empire. There was a time when India and Iran was one land. This book is written by collecting information from various sources available on the internet. ROOTSHUNT 15, Mangalyam Society, Near Ocean Park, Nehrunagar, Ahmedabad – 380 015, Gujarat, BHARAT. M : 0091 – 98792 58523 / Web : www.rootshunt.com / E-mail : [email protected] Contents at a glance : PART - 1 1. Who were Aryans ............................................................................................................................ 1 2. Prehistory of Aryans ..................................................................................................................... 2 3. Aryans - 1 ............................................................................................................................................ 10 4. Aryans - 2 …............................………………….......................................................................................... 23 5. History of the Ancient Aryans: Outlined in Zoroastrian scriptures …….............. 28 6. Pre-Zoroastrian Aryan Religions ........................................................................................... 33 7. Evolution of Aryan worship ....................................................................................................... 45 8. Aryan homeland and neighboring lands in Avesta …...................……………........…....... 53 9. Western -

Kamran Dibat by Erin Mc Cafferty

126 Profiles Kamran Dibat By Erin Mc Cafferty work – colorful and detailed collages in newspaper style is different yet again, making strong statements about trends in globalisation and communication. But then Diba has never been afraid to buck the status quo. Not only an artist but a well respected architect and urban planner, he’s probably most famous for founding, designing and directing the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in the 1970s, which owns one of the richest collections of modern and contemporary artworks in the world. Born in Iran in 1937, he studied architecture and later sociology at Howard University in Washington, graduating in 1964. As a student he taught himself to paint however and it’s clear the emerging contemporary art scene there had a profound influence on his work. He first exhibited in the US in the 1960s, influenced by the likes of Kooning, Rothko and Kline, he participated in group exhibitions such as the Corcoran Gallery annuals in Washington DC Gallery Realites in 1962. The following year he held a one-person exhibition of abstract paintings, also in Washington. As a student Diba had travelled frequently between Tehran and the US and while influenced by his native culture sought a way to express it in a modern form. Inspired by old Persian manuscripts, he began making collages from pieces of Persian carpets. These artworks were nothing if not contemporary and yet were characteristic of an ancient culture which was Untitled, 1961, oil on canvas, 125x84cm - US collection, Courtesy of the artist clearly important to him. He later focused his attention on abstract calligraphy, once again creating a seamless Although intrinsically Iranian, reflecting his country’s dialogue between the modern and ancient worlds. -

Historical Women 26 October, 2019

10/26/2019 Historical Persian Queens, Empresses, Warriors, Generals of Persia PERSEPOLIS 3757 Zoroastrian Holy Year 2578 Charter of Human Rights HISTORICAL WOMEN 26 OCTOBER, 2019 POWERFUL WOMEN OF PERSIA WELCOME INTRODUCTION This section is dedicated to some of the most powerful women of Persia that never received the historical recognition they deserve due to passage of time and accidents of history. Women in Persia were very honored and revered, they often held very important & inuential positions in the Courthouse, Ministries, Military, State and Treasury Department, and other ofcial administrations. The signicant role of women in Ancient Persia both horried and fascinated the ancient Greek and Roman male-dominated societies. The fortication tablets at the Ruins of Persepolis also reveals that men and women were represented in identical professions and that they received equal payments as skilled laborers and that gender was not a criterion at all (unlike our modern world). New mothers and pregnant women even received wages far above those of their male co-workers in order to show appreciation. Women enjoyed a high level of gender equality before the imposition of the dark, backward, and pernicious Abrahamic ideologies (Judaism, Christianity, and especially Islam) after the barbaric Arab invasion upon Persia which destroyed our Equal rights, Freedom of speech and Freedom of religion and replaced those factors with central primitive brutal government, prejudice and slavery. There is much evidence that the principles of Zoroastrianism lay the core foundation to the rst Declaration of Human Rights in the Persian Empire set by Cyrus the Great since the rulers of Persia were Zoroastrians and relatively liberal and progressive.