Engaging the Mental Wars of Our Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Calvin and Witsius on the Mosaic Covenant

1 1 Calvin and Witsius on the Mosaic Covenant J. V. FESKO hen it comes to the Mosaic covenant, an ocean of ink has been spilled by theologians in their efforts to relate it both to WIsrael’s immediate historical context and to the church’s exis- tence in the wake of the advent of Christ. Anthony Burgess (d. 1664), one of the Westminster divines, writes: “I do not find in any point of divinity, learned men so confused and perplexed (being like Abraham’s ram, hung in a bush of briars and brambles by the head) as here.”1 Among the West- minster divines there were a number of views represented in the assembly: the Mosaic covenant was a covenant of works, a mixed covenant of works and grace, a subservient covenant to the covenant of grace, or simply the covenant of grace.2 One can find a similar range of views represented in more recent literature in our own day.3 In the limited amount of space 1. Anthony Burgess, Vindicae Legis (London, 1647), 229. 2. Samuel Bolton, The True Bounds of Christian Freedom (1645; Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 2001), 92–94. 3. See, e.g., Mark W. Karlberg, “Reformed Interpretation of the Mosaic Covenant,” Westmin- ster Theological Journal 43.1 (1981): 1–57; idem, Covenant Theology in Reformed Perspective (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2000), 17–58; D. Patrick Ramsey, “In Defense of Moses: A Confes- sional Critique of Kline and Karlberg,” Westminster Theological Journal 66.2 (2004): 373–400; 25 Estelle Law Book.indd 35 12/12/08 3:36:48 PM 26 J. -

Scottish Journal of Theology 23(1970): 129-156

Scottish Journal of Theology 23(1970): 129-156. R E SPO N S I B L E M A N I N R E FO R M E D TH E O L OG Y: CA L V I N V E R SU S T H E WES T M I N S TE R C ON F ES S I O N by THE REV. PROFESSOR HOLM ES R O LSTON II I HE Confession of 1967 in the United Presbyterian Church marks the official end of the four-century Presbyterian venture into covenant theology. Now past that milestone, perhaps we have reached a vantage point where we can turn dispassion• ately to survey that curious but historic route. Seen from its concept of responsible man, we here argue, that route has been a prolonged detour away from the insights of the Reformers. The Westminster Confession remains, of course, the prime con• fessional document of Presbyterians outside the United Church, for instance in the Scots and British parent churches, or with southern cousins in the Presbyterian Church, U.S. Even in the United Church, the Westminster Confession remains in the show• room of creeds. But we have recently seen a breach in the federal scheme so long embraced in Presbyterian confessional statements, a breach that marks the scheme where it yet re• mains officially as a theological anachronism no longer re• garded seriously but to be suffered as historical background. With the hold of federal theology officially broken, we can challenge afresh the assumption that the Calvinism of the Westminster Confession is true to the Reformer himself. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Radboud Repository PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/61293 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. De weg naar de hel is geplaveid met boeken over de bijbel Vrijgeest en veelschrijver Willem Goeree (1635-1711) Inger Leemans Geen Willem van Nassouw, maar Willem Goederêe, Zoo, als by ‘t Bruylofts-bedde, en ‘t sluyten van een Vrêe; Zoo, als van een, by wien de hooge Wetenschappen Zig voegden by de Konst, niet langs de Schoolsche trappen, Maar Oeffening der Geest Zo wordt in het Panpoëticon Batavum - de eerste Nederlandse literatuurgeschiedenis - Willem Goeree aangekondigd. 1 De schrijver Lambert Bidloo is zich bewust van zijn positie als canonvormer en blijkbaar vormt Goeree een omstreden zaak want met- een daarop laat hij de lezer bezwaren uiten tegen de opname van deze auteur: Gevraagd, hoe komt Goerêe ten Rye der Poëten In ‘t Panpoëticon! naar dien wy weynig weten Van zyne Digt-konst, als het geen men by geval, Verspreydt, of nameloos in ‘t Werk ontmoeten zal; Inderdaad zouden we een veelschrijver als Willem Goeree vandaag ook niet zo snel onder de literaire auteurs plaatsen. In de meeste literatuurgeschiedenissen zoekt men hem dan ook tevergeefs. Een plaats in de wetenschapsgeschiedenis heeft hij evenmin gekregen. Zijn Bijbelse geschiedenissen worden niet meer her- drukt. -

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

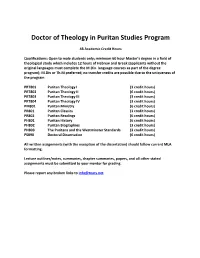

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Curriculum Vitae—Greg Salazar

GREG A. SALAZAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORICAL THEOLOGY PURITAN REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PHD CANDIDATE, THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 2965 Leonard Street Phone: (616) 432-3419 Grand Rapids, MI 49525 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIVE To train and form the next generation of Reformed Christian leaders through a career of teaching and publishing in the areas of church history, historical theology, and systematic theology. I also plan to serve the Presbyterian church as a teaching elder through a ministry of shepherding, teaching, and preaching. EDUCATION The University of Cambridge (Selwyn College) 2013-2017 (projected) PhD in History Dissertation: “Daniel Featley and Calvinist Conformity in Early Stuart England” Supervisor: Professor Alex Walsham Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando 2009-2012 Master of Divinity The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2003-2007 Bachelor of Arts (Religious Studies) DOCTORAL RESEARCH My doctoral research is on the historical, theological, and intellectual contexts of the Reformation in England—specifically analyzing the doctrinal, ecclesiological, and pietistic links between puritanism and the post-Reformation English Church in the lead-up to the Westminster Assembly, through the lens of the English clergyman and Westminster divine Daniel Featley (1582-1645). AREAS OF RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION Broadly speaking, my competency and interests are in church history, historical theology, systematic theology, spiritual formation, and Islam. Specific Research Interests include: Post-Reformation -

William Perkins (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 Pm 1602) Earned a Bachelor’S Plenary Session # 1 Degree in 1581 and a Mas- Dr

MaY 19 (FrIDaY eVeNING) William perkinS (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 pm 1602) earned a bachelor’s plenary Session # 1 degree in 1581 and a mas- Dr. Sinclair Ferguson, ter’s degree in 1584 from WILLIAM William Perkins—A Plain Preacher Christ’s College in Cam- bridge. During those stu- dent years he joined up PERKINS MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY MOrNING) with Laurence Chaderton, CONFereNCe 9:00 - 10:15 am who became his personal plenary Session # 2 tutor and lifelong friend. IN THE ROUND CHURCH Dr. Joel Beeke Perkins and Chaderton met William Perkins’s Largest Case of Conscience with Richard Greenham, Richard Rogers, and others in a spiritual brotherhood 10:30 – 11:45 am at Cambridge that espoused Puritan convictions. plenary Session # 3 Dr. Geoff Thomas From 1584 until his death, Perkins served as lectur- The Pursuit of Godliness in the er, or preacher, at Great St. Andrew’s Church, Cam- Ministry of William Perkins bridge, a most influential pulpit across the street from Christ’s College. He also served as a teaching fellow 12:00 – 6:45 pm at Christ’s College, catechized students at Corpus Free Time Christi College on Thursday afternoons, and worked as a spiritual counselor on Sunday afternoons. In MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY eVeNING) these roles Perkins influenced a generation of young 7:00 – 8:15 pm students, including Richard Sibbes, John Cotton, John plenary Session # 4 Preston, and William Ames. Thomas Goodwin wrote Dr. Stephen Yuille that when he entered Cambridge, six of his instruc- Contending for the Faith: Faith and Love in Perkins’s tors who had sat under Perkins were still passing on Defense of the Protestant Religion his teaching. -

Petrus Van Mastricht (1630-1706)

Adriaan C. Neele (ed.) Petrus van Mastricht (1630–1706) Text, Context, and Interpretation Adriaan C. Neele (ed.): Petrus van Mastricht (1630–1706): Text, Context, and Interpretation © 2020, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525522103 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647522104 Adriaan C. Neele (ed.): Petrus van Mastricht (1630–1706): Text, Context, and Interpretation Reformed Historical Theology Edited by Herman J. Selderhuis in Co-operation with Emidio Campi, Irene Dingel, Benyamin F. Intan, Elsie Anne McKee, Richard A. Muller, and Risto Saarinen Volume 62 © 2020, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525522103 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647522104 Adriaan C. Neele (ed.): Petrus van Mastricht (1630–1706): Text, Context, and Interpretation Adriaan C. Neele (ed.) Petrus vanMastricht (1630–1706): Text, Context, and Interpretation With aForeword by Carl R. Trueman Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2020, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525522103 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647522104 Adriaan C. Neele (ed.): Petrus van Mastricht (1630–1706): Text, Context, and Interpretation Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek: The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data available online: https://dnb.de. © 2020, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 Göttingen All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher. Typesetting: 3w+p, Rimpar Printed and bound: Hubert & Co. BuchPartner, Göttingen Printed in the EU Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISSN 2197-1137 ISBN 978-3-647-52210-4 © 2020, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. -

Preparation for Grace in Puritanism: an Evaluation from the Perspective of Reformed Anthropology

Diligentia: Journal of Theology and Christian Education E-ISSN: 2686-3707 ojs.uph.edu/index.php/DIL Preparation for Grace in Puritanism: An Evaluation from the Perspective of Reformed Anthropology Hendra Thamrindinata Faculty of Liberal Arts, Universitas Pelita Harapan [email protected] Abstract The Puritans’ doctrine on the preparation for grace, whose substance was an effort to find and to ascertain the true marks of conversion in a Christian through several preparatory steps which began with conviction or awakening, proceeded to humiliation caused by a sense of terror of God’s condemnation, and finally arrived into regeneration, introduced in the writings of such first Puritans as William Perkins (1558-1602) and William Ames (1576-1633), has much been debated by scholars. It was accused as teaching salvation by works, a denial of faith and assurance, and a divergence from Reformed teaching of human's total depravity. This paper, on the other hand, suggesting anthropology as theological presupposition behind this Puritan’s preparatory doctrine, through a historical-theological analysis and elaboration of the post-fall anthropology of Calvin as the most influential theologian in England during Elizabethan era will argue that this doctrine was fit well within Reformed system of believe. Keywords: Puritan, Reformed Theology, William Perkins, William Ames, England, Grace. Introduction In his book on Jonathan Edwards’s biography, Marsden tells a story about Edwards’s struggle with a question related to his spirituality, whether -

Johannes Cocceius on Covenant

MJT 14 (2003) 37-57 EXPROMISSIO OR FIDEIUSSIO? A SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY THEOLOGICAL DEBATE BETWEEN VOETIANS AND COCCEIANS ABOUT THE NATURE OF CHRIST’S SURETYSHIP IN SALVATION HISTORY by Willem J. van Asselt Voetians and Cocceians TOWARDS THE END of the seventeenth century a controversy erupted over the interpretation of the relation between the historical death of Christ and the associated doctrine of the forgiveness of sins. This controversy had its origin in the dissemination of the ideas of the Leyden professor Johannes Cocceius (1603-1669) and his followers. Resistance to these ideas came from the followers of the Utrecht professor Gisbertus Voetius (1587-1676). The discussion centered on the interpretation of the concept of Christ’s sponsio or suretyship and was essentially an intensification of standing differences between these two strands in the Reformed Church of the seventeenth century, namely, on the interpretation of the fourth commandment (the Sabbath) and the doctrine of justification. While these issues may initially seem of merely academic interest, much more proved to be at stake as the debate developed. The theological quarrel had repercussions at the social and political level, and worked as a catalyst in the formation of group identity. Although the altercations between Voetians and Cocceians continued far into the eighteenth century, they were not as destructive as the Arminian/Gomarian conflict of the first half of the seventeenth century. Voetians and Cocceians continued to worship in the same church, and accepted a degree of pluriformity in church practice. To understand why the quarrels between Voetians and Cocceians dominated the life of the Republic for so long, one has to realize the extent of the uneasiness among 38 • MID-AMERICA JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY members of the Reformed Church over the rise of the new Cartesian philosophy and certain developments in natural science. -

William B. Hunter Argues

SEL 32 (1992) ISSN 0039-3657 The Provenance of the Christian Doctrine WILLIAM B. HUNTER The year 1991 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Maurice Kelley's This Great Argument with the subtitle A Study of Milton's "De Doctrina Christiana" as a Gloss upon "Paradise Lost".' One can make a good case that it has been the most influential work of Milton scholarship published in this century; on this an- niversary it is appropriate to review its successes and failures, and especially its fruitful thesis that the theological treatise provides a major interpretative gloss for the poem, as its subtitle states. Such a fertile theory has given inspiration to others who have applied it to the rest of Milton's poetry and prose, especially the later works. It is safe to say that lacking the thesis of This Great Argument, Bright Essence would not exist and Milton's Brief Epic, Toward Samson Agonistes, and Milton and the English Revolution would be quite different books from the ones we know.2 Significant too is the fact that Kelley saw no cause to change his arguments radically during the rest of his productive career. He was the obvious choice to edit the Christian Doctrine for the sixth volume of the Yale Prose. Its extensive introduction is to a considerable extent a recapitulation and occasional expansion of the work printed over thirty years earlier. Indeed, as Kelley himself observes, he sometimes repeated the earlier argument word for word in the introduction to the edition.3 In view of the heterodoxy of much of the Christian Doctrine, Milton is now interpreted in many of his works, not just in the treatise, as a heretic-the opposite from the views that almost William B.