Norwegian Labour History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jorunn Bjørgum Veien Til Komintern Martin Tranmæl Og Det

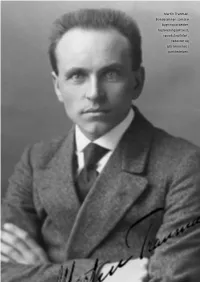

Martin Tranmæl. Bondesønnen som ble bygningsarbeider, fagforeningsaktivist, sosialistagitator , redaktør og grå eminense i partiledelsen. Jorunn BJørguM Veien til Komintern Martin Tranmæl og det internasjonale spørsmål 1914–19 Hvordan kan vi forklare at Martin Tranmæl i 1919 gikk inn for at Det norske Arbeiderparti skulle bryte opp fra den gamle sosialistiske 2. Inter nasjonalen og i stedet slutte seg til Komintern? Det er hovedproblemstil lingen i denne artikkelen.1 Martin Tranmæl var en ruvende lederskikkelse i norsk arbeiderbeve gelse i over to mannsaldre. Forut for 1918 var han opposisjonsleder. gjennom hele mellomkrigstiden var han Arbeiderpartiets reelle politiske leder. og i etterkrigstiden var han en sentral politisk bakspiller eller grå eminense i partiledelsen. Han var medlem av Arbeiderpartiets landsstyre fra 1906 og av sentralstyret fra 1918 og helt fram til 1963. I storparten av tiden var han også medlem av Los sekretariat og av samarbeids komiteen mellom Arbeiderpartiet og Lo.2 Han utøvde sitt lederskap dels gjennom de formelle organene han deltok i, dels gjennom stillingen som redaktør og dels gjennom personlig påvirkning på partiformennene oscar Torp og Einar gerhardsen, som han selv hadde rekruttert til parti ledelsen i 1923. Så hvordan kunne det ha seg at denne sentrale sosialdemokraten i 1919 gikk inn for at Arbeiderpartiet skulle melde seg inn i Lenins nye kommunistiske internasjonale? utgangspunktet var radikaliseringen av norsk arbeiderbevegelse under første verdenskrig, da Tranmæl stod i spissen for partiopposisjonen, den nye retning. Den overtok ledelsen av Arbeiderpartiet på landsmøtet i 1918 og fikk vedtatt sin parole revolu sjonær masseaksjon som partiets nye politiske strategi.3 Tranmæl ble ny partisekretær og hans nære venn og politiske medarbeider, Kyrre grepp, ny partiformann. -

ECSP Report 6

Features Environmental Change & Security Project REPORT ISSUE NO. 6 • THE WOODROW WILSON CENTER • SUMMER 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURES X5 Human Population and Environmental Stresses in the Twenty-first Century Richard E. Benedick 19 Oiling the Friction: Environmental Conflict Management in the Niger Delta, Nigeria Okechukwu Ibeanu SPECIAL REPORTS 33 The Global Infectious Disease Threat and Its Implications for the United States National Intelligence Council 66 Exploring Capacity for Integration: University of Michigan Population-Environment Fellows Programs Impact Assessment Project Denise Caudill COMMENTARY 77 Environment, Population, and Conflict Geoffrey D. Dabelko Ted Gaulin Richard A. Matthew Tom Deligiannis Thomas F. Homer-Dixon Daniel M. Schwartz 107 Trade and the Environment Martin Albrow Andrea Durbin Kent Hughes Stephen Clarkson Mikhail Gorbachev Anju Sharma William M. Daley Tamar Gutner Stacy D. VanDeveer OFFICIAL STATEMENTS AND DOCUMENTS 119 William J. Clinton; Albert Gore, Jr.; Madeleine K. Albright; David B. Sandalow; Benjamin A. Gilman; George W. Bush; Kofi Annan; Mark Malloch Brown; Klaus Töpfer; Nafis Sadik; Gro Harlem Brundtland ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE & SECURITY PROJECT REPORT, ISSUE 6 (SUMMER 2000) 1 Features 132 NEW PUBLICATIONS Environmental Change, Adaptation, and Security 132 Ecology, Politics, and Violent Conflict 135 Hydropolitics in the Third World: Conflict and Cooperation in International River Basins 136 Violence Through Environmental Discrimination: Causes, Rwanda Arena, and Conflict Model 139 The Sustainability -

Småbrukarorganisering Og Arbeidarrørsle*)

Tidsskrift for arbeiderbevegelsens historie, 1. 1980. Sigvart Tøsse Småbrukarorganisering og arbeidarrørsle*) I 1938 skreiv historikaren Wilhelm Keilhau at småbrukarane sin oppmarsj var «den mest bemerkede kjensgjerning i det norske jordbruks utviklingshistorie mellom 1905 og 1914».'). Eit resul tat av denne oppmarsjen var danninga av Norsk Småbrukerfor- bund i 1913. Artikkelen vil ta opp bakgrunnen for denne organi- sasjonsdanninga og utviklinga fram til slutten av 1920 åra. I tiåret før første verdenskrig skjedde også gjennombrotet for fagorganisasjonen og Det norske arbeiderparti. I 1912 organi serte skog- og landarbeidarane seg i eit eige forbund som slutta seg til Arbeidernes faglige landsorganisasjon. I Småbrukarfor- bundet dominerte folk frå Arbeidardemokratane. Den geograf iske basisen for begge forbunda var Austlandet, serleg Hedmark og Oppland. Småbrukarforbundet fekk ikkje den store tilslut ninga, men klarte seg over ei nedgangstid i 20 åra og byrjinga av 30 talet. Norsk skog- og jordbruksarbeiderforbund frå 1912 gjekk derimot i oppløysing i byrjinga av 1920 talet. Politisk var Arbeidarpartiet på frammarsj. Det store gjennombrotet på byg dene i Austlandet kom ved valet i 1927 som viser masseover- gang frå dei tidlegare arbeidardemokratveljarane. Eit interessant aspekt som vil bli teke opp her, er da tilhøvet mellom småbruka- rorganisasjonen og arbeidarrørsla. Men først spør vi om kvifor Norsk Småbrukerforbund blei danna, og kva var dei økonomi ske, sosiale og politiske føresetnadene for ein slik organisasjon? *) Artikkelen byggjer vesentleg på hovudoppgåva mi i historie-. Norsk bonde- og småbrukarlag 1913-28. Bakgrunn og verksemd. Trondheim 1976. Økonomisk og sosial bakgrunn Jordbrukstellinga i 1907 - den første serskilte jordbrukstellinga - viste store endringar frå tidlegare statistiske oversikter. Stats minister Gunnar Knudsen sa at tellinga opna augo hans for kor utprega eit småbruksland Norge var. -

Gro Harlem Brundtland

Gro Harlem Brundtland First woman Prime Minister of Norway and Deputy Chair of The Elders; a medical doctor who champions health as a human right; put sustainable development on the international agenda. Deputy Chair of The Elders Norway's first woman Prime Minister Director-General of the World Health Organization 1998-2003 UN Special Envoy on Climate Change "We are individuals who are speaking without any outside pressures. In that context we can create the potential for change." Work with The Elders Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland has been a member of The Elders its founding in 2007, bringing to the group her decades of experience as a global leader in public health and sustainable development. She has served as Deputy Chair since May 2013. As part of The Elders’ peace-building agenda, Dr Brundtland joined The Elders’ first delegation to Israel and the West Bank in August 2009 to support efforts to advance Middle East peace – paying particular attention to the impact of the conflict on ordinary Israelis and Palestinians. She has travelled to Greece, Turkey and Cyprus to encourage reconciliation between Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities. In April 2011 she joined an Elders delegation to the Korean Peninsula and China in an effort to improve relations between North and South Korea. A staunch advocate of gender equality as a prerequisite for development, Dr Brundtland travelled to Ethiopia in June 2011 to meet communities affected by child marriage and bring together experts and activists working to end this harmful practice. In February 2012 she travelled to India, where the Elders lent their support to youth activists tackling early marriage at the local level. -

Beretning 1913

.. " . DET NORSKE ARBEIDERPARTI ........................................................................................................ BERETNINGFOR 1913 I AARET UT ARBEIDET VED SEKRET ÆREN I Il'i ,, ........................................................................................................ KRISTIANIA 1914 :: ARBEIDERNES AKTIETRYKKERI Indholdsfortegnelse. Centralstyrets beretning. ide Hedemarken. 'ide Solør arbeiderparti . 28 .\.aret 1913 (over igt . 1 Eidskog, Vinger og Odalen arb.p. 30 Landsstyret . 2 . Søndre Hedemarkens kredsparti 30 Centralstyret . 2 Nordre Hedemarkens arb.parti . 31 Nye organisationer . 2 Søndre Østerdalen arb.parti . 31 Strøkne organisationer . 3 Xordre Østerdalens kredsparti 32 Amtspartternes omorganisation . 3 Kristian. 1. 8maalene amtsparti . 3 Jevnaker arbeiderparti . 32 2. Akershus amtsparti ... 4 Bu�kerud. 3. Hedemarkens amt parti . 4 Buskerud amtsparti . 33 4. Buskerud amtsparti . 5 Numedals kredsparti . 35 5. Brat berg amtsparti . 5 Jarlsberg og Larvik. Agitationen . 5 koger kred arbeiderparti . 35 1. mai .. ...... 9 Brunla kredsparti . 35 Kommunevalgene . 9 Bratsberg. 1. Landkommunerne . 10 Brat berg amtsparti . 36 2. Byerne . 11 Vest-Telemarkens kred parti 37 3. ICvinderne og valget . 11 Nedenes. 4. Valgets hovedre ultat 12 Nedene amtsparti . 37 Brochurer . 13 Lister og Man dal. Partiets forlag og bokhandel . 14 Oddernes kreds arbeiderparti 38 Det tyvende aarhundrede . 15 .Mandalens kred sparti . 38 Kommunalt tidssknft . 15 Stavanger amt. Partiet pre se . 15 Stavanger amtsparti . 38 Haand -

Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education

Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education The portrayal of the Russian Revolution of 1917 in the Norwegian labor movement A study of the editorials of the Social-Demokraten, 1915—1923 Anzhela Atayan Master’s thesis in Peace and Conflict Transformation – SVF-3901 June 2014 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Kari Aga Myklebost for helpful supervision with practical advice and useful comments, the Culture and Social Sciences Library, the Centre for Peace Studies and Ola Goverud Andersson for support. iii iv Morgen mot Russlands grense Jeg kommer fra dagen igår, fra vesten, fra fortidens land. Langt fremme en solstripe går mot syd. Det er morgenens rand. I jubel flyr toget avsted. Se grensen! En linje av ild. Bak den er det gamle brendt ned. Bak den er det nye blitt til. Jeg føler forventningens sang i hjertets urolige slag. Så skulde jeg også engang få møte den nye dag! Rudolf Nilsen v vi Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………….......1 1.1.Major terms and choice of period……...………………………………………………......1 1.2.Research questions…………………………………………………………………………2 1.3.Motivation and relevance for peace studies………………………………………………..3 1.4.Three editors: presentation…………………………………………………………………3 1.5.The development of the Norwegian labor press: a short description………………………6 1.6.The position of the Norwegian labor movement in Scandinavia…………………………..7 1.7.Structure of the thesis............................................................................................................8 Chapter 2. Previous studies and historical background………………………………………11 2.1. Previous studies…………………………………………………………………………..11 2.2. Historical background……………………………………………………………………14 2.2.1. The situation in Norway…………………………………………………………...14 2.2.2. Connections between the Bolsheviks and the Norwegian left…………….……....16 Chapter 3. -

Cross-Border Ties Among Protest Movements the Great Plains Connection

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Spring 1997 Cross-Border Ties Among Protest Movements The Great Plains Connection Mildred A. Schwartz University of Illinois at Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Schwartz, Mildred A., "Cross-Border Ties Among Protest Movements The Great Plains Connection" (1997). Great Plains Quarterly. 1943. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1943 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CROSS .. BORDER TIES AMONG PROTEST MOVEMENTS THE GREAT PLAINS CONNECTION MILDRED A. SCHWARTZ This paper examines the connections among supporters willing to take risks. Thus I hypoth political protest movements in twentieth cen esize that protest movements, free from con tury western Canada and the United States. straints of institutionalization, can readily cross Protest movements are social movements and national boundaries. related organizations, including political pro Contacts between protest movements in test parties, with the objective of deliberately Canada and the United States also stem from changing government programs and policies. similarities between the two countries. Shared Those changes may also entail altering the geography, a British heritage, democratic prac composition of the government or even its tices, and a multi-ethnic population often give form. Social movements involve collective rise to similar problems. l Similarities in the efforts to bring about change in ways that avoid northern tier of the United States to the ad or reject established belief systems or organiza joining sections of Canada's western provinces tions. -

James Connolly and the Irish Labour Party

James Connolly and the Irish Labour Party Donal Mac Fhearraigh 100 years of celebration? to which White replied, `Put that furthest of all1' . White was joking but only just, 2012 marks the centenary of the founding and if Labour was regarded as conservative of the Irish Labour Party. Like most politi- at home it was it was even more so when cal parties in Ireland, Labour likes to trade compared with her sister parties. on its radical heritage by drawing a link to One historian described it as `the most Connolly. opportunistically conservative party in the On the history section of the Labour known world2.' It was not until the late Party's website it says, 1960s that the party professed an adher- ence to socialism, a word which had been `The Labour Party was completely taboo until that point. Ar- founded in 1912 in Clonmel, guably the least successful social demo- County Tipperary, by James cratic or Labour Party in Western Europe, Connolly, James Larkin and the Irish Labour Party has never held office William O'Brien as the polit- alone and has only been the minority party ical wing of the Irish Trade in coalition. Labour has continued this tra- Union Congress(ITUC). It dition in the current government with Fine is the oldest political party Gael. Far from being `the party of social- in Ireland and the only one ism' it has been the party of austerity. which pre-dates independence. The founders of the Labour The Labour Party got elected a year Party believed that for ordi- ago on promises of burning the bondhold- nary working people to shape ers and defending ordinary people against society they needed a political cutbacks. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy

Luke Howson University of Liverpool The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy By Luke Howson July 2014 Committee: Clive Jones, BA (Hons) MA, PhD Prof Jon Tonge, PhD 1 Luke Howson University of Liverpool © 2014 Luke Howson All Rights Reserved 2 Luke Howson University of Liverpool Abstract This thesis focuses on the role of ultra-orthodox party Shas within the Israeli state as a means to explore wider themes and divisions in Israeli society. Without underestimating the significance of security and conflict within the structure of the Israeli state, in this thesis the Arab–Jewish relationship is viewed as just one important cleavage within the Israeli state. Instead of focusing on this single cleavage, this thesis explores the complex structure of cleavages at the heart of the Israeli political system. It introduces the concept of a ‘cleavage pyramid’, whereby divisions are of different saliency to different groups. At the top of the pyramid is division between Arabs and Jews, but one rung down from this are the intra-Jewish divisions, be they religious, ethnic or political in nature. In the case of Shas, the religious and ethnic elements are the most salient. The secular–religious divide is a key fault line in Israel and one in which ultra-orthodox parties like Shas are at the forefront. They and their politically secular counterparts form a key division in Israel, and an exploration of Shas is an insightful means of exploring this division further, its history and causes, and how these groups interact politically. -

4 Institutional Change in Norway: the Importance of the Public Sphere6

Gunnar C. Aakvaag 4 Institutional Change in Norway: The Importance of the Public Sphere6 The goal of this chapter is to provide a new and better theoretical account of the overall pattern of institutional change in modern Norway by emphasizing the importance of the public sphere. One effective way to describe the modernization of Norway is as a cumulative process whereby new categories of individuals – peasants, workers and women – have gradually been included as full members in society (Koht, 1953; Furre, 2000; Slagstad, 1998, pp. 417–418; Rokkan, 2010; Sejersted, 2005, 2000, pp. 18–20 and 23–25). This social transformation has taken place through large-scale institutional changes that sociologists need to explain. This chapter argues that the four currently dominating theoretical models of institutional change are not fully up to this task for two reasons. Models that accentuate either external shocks or incremental accumula- tion cannot account for the highly ‘political’, goal-oriented and reflexively monitored aspect of overall institutional change in Norway, whilst the two dominant models of political collective decision making, voting and bargaining, cannot account for the high level of consensus that have fed into processes of institutional change both as their input and outcome. To overcome these deficits, this chapter takes a different approach, what might be called ‘deliberative’ or ‘discursive’ institutionalism (Schmidt 2008). It emphasizes what has been an essential aspect of Norwegian society at least since the middle of the -

Images of Male Political Leaders in France and Norway

Reconsidering Politics as a Man's World: Images of Male Political Leaders in France and Norway Anne Krogstad and Aagoth Storvik Researchers have often pointed to the masculine norms that are integrated into politics. This article explores these norms by studying male images of politics and power in France and Norway from 1945 to 2009. Both dress codes and more general leadership styles are discussed. The article shows changes in political aesthetics in both countries since the Second World War. The most radical break is seen in the way Norwegian male politicians present themselves. The traditional Norwegian leadership ethos of piety, moderation, and inward orientation is still important, but it is not as self- effacing and inelegant as it used to be. However, compared to the leaders in French politics, who still live up to a heroic leadership ideal marked by effortless superiority and seduction, the Norwegian leaders look modest. To explain the differences in political self-presentation and evaluation we argue that cultural repertoires are not only national constructions but also gendered constructions. Keywords: photographs; politics; aesthetics; gender; national cultural repertoires 1 When people think of presidents and prime ministers, they usually think of the incumbents of these offices.1 In both France and Norway, these incumbents have, with the exception of Prime Minister Edith Cresson in France and Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland in Norway, been male (and white). Researchers have often pointed to the masculine norms which are integrated into the expectations of what political officeholders should look like and be. Politics, it is claimed, is still very much a man’s world.2 However, maleness does not express general political leadership in a simple and undifferentiated way.