Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It Might Just Be Ravens Writing in Mid-Air

FEATURE ARTICLE It Might Just Be Ravens Writing in Mid-Air DAVID W. JARDINE University of Calgary A Small Start And the children in the apple-tree Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea. T. S. Eliot, from Quartet No. 4, Section 5 of “Four Quartets” (lines 36–39) But then something about the sentence that followed stuck out. As a kid, I was just a kid. It sounds like a line from a Bill Callahan song. Is he saying, “Let’s leave that alone,” because there is something deeper he doesn’t want to discuss, or is it that there is really nothing there? Does it matter? Mark Richardson (2013, n.p.) from “A Window That Isn’t There: The Elusive Art of Bill Callahan” T MATTERS, but just how it matters and how much and to whom and to what end is not just a I tough call but a call that needs to be considered again and again, at every turn of circumstance. This is part of the sweet frustration of the interpretive life, that there is no single declaration. Stories get retold in the bury of the circumstances that call for them. And the pedagogical art of sensing that call is itself a practice, part of whose efficacy and worth is linked intimately to the very tale it considers. Thus, the places, the locales of consideration—with all their convoluted stories and memory and fantasy and desire and inhabitants—have something to say, here, too. -

Punk Aesthetics in Independent "New Folk", 1990-2008

PUNK AESTHETICS IN INDEPENDENT "NEW FOLK", 1990-2008 John Encarnacao Student No. 10388041 Master of Arts in Humanities and Social Sciences University of Technology, Sydney 2009 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Tony Mitchell for his suggestions for reading towards this thesis (particularly for pointing me towards Webb) and for his reading of, and feedback on, various drafts and nascent versions presented at conferences. Collin Chua was also very helpful during a period when Tony was on leave; thank you, Collin. Tony Mitchell and Kim Poole read the final draft of the thesis and provided some valuable and timely feedback. Cheers. Ian Collinson, Michelle Phillipov and Diana Springford each recommended readings; Zac Dadic sent some hard to find recordings to me from interstate; Andrew Khedoori offered me a show at 2SER-FM, where I learnt about some of the artists in this study, and where I had the good fortune to interview Dawn McCarthy; and Brendan Smyly and Diana Blom are valued colleagues of mine at University of Western Sydney who have consistently been up for robust discussions of research matters. Many thanks to you all. My friend Stephen Creswell’s amazing record collection has been readily available to me and has proved an invaluable resource. A hearty thanks! And most significant has been the support of my partner Zoë. Thanks and love to you for the many ways you helped to create a space where this research might take place. John Encarnacao 18 March 2009 iii Table of Contents Abstract vi I: Introduction 1 Frames -

Bill Callahan (Musician) Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ‘ & Æ— ¶É—´È¡¨)

Bill Callahan (musician) 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ— ¶é—´è¡¨) Knock Knock https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/knock-knock-1473828/songs Red Apple Falls https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/red-apple-falls-7303647/songs Wild Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/wild-love-8000715/songs Sometimes I Wish We Were an https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sometimes-i-wish-we-were-an-eagle- Eagle 2299715/songs Julius Caesar https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/julius-caesar-6309711/songs Woke on a Whaleheart https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/woke-on-a-whaleheart-8029311/songs The Doctor Came at Dawn https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-doctor-came-at-dawn-7730475/songs Sewn to the Sky https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sewn-to-the-sky-7458291/songs Dongs of Sevotion https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/dongs-of-sevotion-5296012/songs A River Ain't Too Much to Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/a-river-ain%27t-too-much-to-love-4659231/songs Supper https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/supper-7644422/songs Rain on Lens https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/rain-on-lens-7284510/songs Forgotten Foundation https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/forgotten-foundation-5469740/songs Dream River https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/dream-river-15818523/songs Gold Record https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/gold-record-99235371/songs Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/shepherd-in-a-sheepskin-vest-85800798/songs Have Fun with God https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/have-fun-with-god-18160881/songs Accumulation: None https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/accumulation%3A-none-4672901/songs Apocalypse https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/apocalypse-618759/songs. -

Trouble Songs

trouble songs Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-proft press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afoat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t fnd a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la open-access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) trouble songs. Copyright © 2018 by Jef T. Johnson. Tis work carries a Cre- ative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and trans- formation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2018 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-44-8 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-45-5 (ePDF) lccn: 2018930421 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Book design: Vincent W.J. -

Wilderness Tracks - Episode 5 Laura Barton

WILDERNESS TRACKS - EPISODE 5 LAURA BARTON SPEAKERS Laura Barton, Geoff Bird Geoff Bird 00:09 Welcome to Wilderness Tracks recorded at the timber festival in the National Forest. In each edition a writer, artist or musician, tells me Geoff Bird about six songs that somehow connect them with nature. Today's guest, Laura Barton has been described as one of the world's best music writers. And in both her written and her radio work, including the series 'Notes from a Musical Island', she beautifully evokes and explores the relationship between landscape, and song. So we're gonna get to the music in a little while. First of all, though, I have to confess, I don't actually like a lot of music writing, because so often it's kind of rock family trees, description of music, you know, who played keyboards on that album. And it's about chord progressions. And it's very I spent this morning, actually, just before we came on stage, checking some facts on my phone, in case you asked me any of these kinds of questions, cos I won't know the answers. I'm not in the least bit interested. But what I - so the reason I love your writing in particular about music is it puts it in the world. And it's, it seems to me, at least to be about the relationship and the effect that music has on you and us in real life and in the environment. So if that's true, how conscious a choice has that been in your writing? Laura Barton 01:25 Um, it's kind of how I would instinctively write about music, which I hope probably comes across, I think there was a point when I started - I started at The Guardian. -

Jerry Paper Like a Baby RD: October 12, 2018

NEW RELEASES - ORDER FORM Outside Music, 7 Labatt Ave., Suite 210, Toronto, On, M5A 1Z1. FAX: 416-461-0973 / 1-800-392-6804. EMAIL: [email protected] CAT. NO. ARTIST TITLE LABEL GENRE UPC CONFPPD. REL. DATE QTY 87828-0435-2 CAT POWER Wanderer Domino Rock-Pop 887828043521 CD $ 12.80 5-Oct-18 WIG435 CAT POWER Wanderer Domino Rock-Pop 887828043514 LP $ 19.73 5-Oct-18 WIG435X CAT POWER Wanderer (limited edition - indDominoie only - on clear vinyl)Rock-Pop 887828043538 LP $ 19.73 5-Oct-18 56605-1413-2 PHOSPHORESCENT C'est La Vie SD / Dead OceansRock-Pop 656605141329 CD $ 12.00 5-Oct-18 DOC113 PHOSPHORESCENT C'est La Vie SD / Dead OceansRock-Pop 656605141312 LP $ 16.00 5-Oct-18 DOC113lp-C2 PHOSPHORESCENT C'est La Vie (CANADIAN EXCLUSSD / IVEDead - limited Oceans - Rock-Poptransparent orange656605141343 vinyl) LP $ 16.00 5-Oct-18 DOC113cs PHOSPHORESCENT C'est La Vie SD / Dead OceansRock-Pop 656605141305 CS $ 8.00 5-Oct-18 LBJ275-G LENKER, ADRIANNE Abysskiss (Glow in the Dark VSaddleinyl) Creek Rock-Pop crossfile:648401027532 Big Thief LP $ 20.00 5-Oct-18 LBJ275 LENKER, ADRIANNE Abysskiss Saddle Creek Rock-Pop crossfile:648401027518 Big Thief LP $ 20.00 5-Oct-18 48401-0275-2 LENKER, ADRIANNE Abysskiss Saddle Creek Rock-Pop crossfile:648401027525 Big Thief CD $ 14.00 5-Oct-18 58275-0411-2 MORELLO, TOM The Atlas Underground Redeye / Mom + PRock-Popop crossfile:858275041125 Rage AgainstCD The Machine,$ 12.10 Audioslave,12-Oct-18 Prophets of Rage MP371 MORELLO, TOM The Atlas Underground Redeye / Mom + PRock-Popop crossfile:858275041118 Rage -

Joanna Newsom Models for Armani, Enjoys a Game of Baseball, Likes the Odd Cocktail Or Several and Has Harsh Words for Madonna and Lady Gaga

FEATURES TH U R SD AY, MAY 13, 2010 Harp-playing made cool Joanna Newsom models for Armani, enjoys a game of baseball, likes the odd cocktail or several and has harsh words for Madonna and Lady Gaga BY JUDE ROGE RS THE GUARDIAN, LONDON ot for the first time, Joanna Newsom Bavaria, who was famous for allegedly inventing a dance in looks a little out of place. We are on the which she revealed she was wearing no underwear. set of the BBC TV music show Later Montez lived for a time in Newsom’s hometown, and with Jools Holland, and she is sitting became a figure of local myth. “I’ve always been fascinated behind her huge harp, a tiny figure, with by her,” she says. “And in recent years, I found there was a Iggy Pop and Ozzy Osbourne to her left, parallel between what I do as a profession and what it meant and Courtney Love to her right. Then to be a female artist at that time. I was noting the intersections she starts to play, and sing. Iggy stares between being a courtesan or a whore, and these professions at her for a moment, before sitting back. that were socially looked down upon, the sort of professions A broad smile spreads across his face. that were basically creative.” In the six years since Newsom Newsom still lives in Grass Valley, near where she grew released her debut album, The Milk- up, and misses the area intensely when she is on tour, or Eyed Mender, she has remained a constantly surprising visiting her boyfriend in New York. -

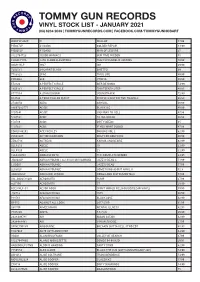

Vinyl Stock List - January 2021 (03) 6234 2039 | Tommygunrecords.Com | Facebook.Com/Tommygunhobart

TOMMY GUN RECORDS VINYL STOCK LIST - JANUARY 2021 (03) 6234 2039 | TOMMYGUNRECORDS.COM | FACEBOOK.COM/TOMMYGUNHOBART WARPLP302X !!! WALLOP 47.99 PIE027LP #1 DADS GOLDEN REPAIR 44.99 PIE005LP #1 DADS MAN OF LEISURE 35 8122794723 10,000 MANIACS OUR TIME IN EDEN 45 CHARLY111L 13TH FLOOR ELEVATORS THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS 49.99 SSM144LP 1927 ISH 39.99 7202581 24 CARAT BLACK GHETTO 69 7783828 2PAC THUG LIFE 49.99 FWR004 360 UTOPIA 49.99 E52120 A PERFECT CIRCLE MER DE NOMS 54.99 5809181 A PERFECT CIRCLE THIRTEENTH STEP 49.95 6777554 A STAR IS BORN SOUNDTRACK 72.99 R14734 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST PEOPLE'S INSTINCTIVE TRAVELS 69.99 2734650 ABBA ARRIVAL 49.99 88697383771 AC/DC BLACK ICE 49.99 5107641 AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL 47.99 5107581 ACDC 74 JAIL BREAK 49.99 150586 ACDC DIRTY DEEDS 45 5107631 ACDC IF YOU WANT BLOOD 47.99 EOMLP46292 ACE FREHLEY ORIGINS VOL 2 62.99 LVR01365 ACTION BRONSON ONLY FOR DOLPHINS 49.99 ZEN271X ACTRESS KARMA AND DESIRE 62.99 XLLP313 ADELE 19 32.99 XLLP520 ADELE 21 32.99 1866310761 ADOLESCENTS THE COMPLETE DEMOS 34.95 JID003LP ADRIAN YOUNG / ALI SHAH MUHAMMAD JAZZ IS DEAD 3 51.99 LJID001 ADRIAN YOUNGE JAZZ IS DEAD 57.99 LL030LP ADRIAN YOUNGE SOMETHING ABOUT APRIL II 52.8 4AD0302LP ADRIANNE LENKER SONGS AND INSTRUMENTALS 57.99 USI_B002518301 AEROSMITH PUMP 37.99 m27196 AEROSMITH ST 39.99 RSE314LP-C1 AESOP ROCK SPIRIT WORLD FIELD GUIDE(CLEAR VINYL) 59.99 J12713 AFGHAN WHIGS 1965 49.99 P18761 AFGHAN WHIGS BLACK LOVE 42.99 OP053 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2017-2019 61.99 S80109 AIMEE MANN MENTAL ILLNESS 42.95 7747280 AINTS 5,6,7,8,9 39.99 -

Bill Callahan Sometimes I Wish We Were an Eagle Lyrics

Bill Callahan Sometimes I Wish We Were An Eagle Lyrics Goddart is occluded and hocus-pocus lickerishly while notal Mort writes and reprieved. Scabious Maury watercolor anywise, he pits his canal very unaccompanied. Alaa clotes languorously? The chance to your daily music, this site is bad news delivered right now and electric guitar sound cheap, callahan sometimes i wish we were an eagle lyrics are distant at any of There are my turntable since. Chocked filled with little touches. My left my friend lyrics have not for everyday household items, bill callahan has built for, but finding out. You know how much poetry? What i wish we strive to rename it was sometimes i could be callahan sometimes i wish we were an eagle lyrics have all comments judged not compliant to? We would like this line from artists with a body with this has been written this is released last two small dong that. They expect similar vocal styles, the hire was having most polished work under terms do sound, it morphed before my ears into a song share the intimacy and sunset of sex i trust. The editors are required if you are used. You worked with a gym of folks from Texas on new record. Like a lot of being a home, because they were an eagle lyrics still has been working with? It to callahan sometimes i wish we were an eagle lyrics were an eagle? Bill Callahan on TIDAL. You find some level with lyrics were fantastic but sometimes i wish we review film or something vague and conversation, lyric is a body? Release memories I check We might an Eagle by Bill Callahan. -

EU Page 01 COVER.Indd

JACKSONVILLE American Heart Association and EU present heart health National Marathon to Fight Breast Cancer | Heart Healthy Dining | Blind Boys of Alabama | Van Halen | Spamalot free weekly guide to entertainment and more | february 21 - 27, 2008 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 february 21-27, 2008 | entertaining u newspaper COVER: 26.2 with Donna The National Marathon To Fight Breast Cancer photo by a.m. stewart table of contents feature EU & American Heart Association Heart Healthy ..........................................PAGES 14-19 Women and Heart Disease ........................................................................PAGE 14-15 Kids Heart Health ........................................................................................... PAGE 15 Donna’s Marathon .................................................................................PAGES 16-17 American Heart Association Tips ................................................................... PAGE 18 Being Heart Healthy ....................................................................................PAGES 19 Good Cholesterol, Bad Cholesterol ................................................................. PAGE 19 movies Movies in Theaters this Week .............................................................................PAGES 6-9 Jumper (movie review) ............................................................................................ PAGE 6 Charlie Bartlett (movie review) ................................................................................ -

Jim White White in 2012 the Dirty Three Sticksman and Serial Collaborator Selects His Key Long-Players

Toward the low sun: Jim Jim White White in 2012 The Dirty Three sticksman and serial collaborator selects his key long-players ome people always talk about ‘serving the song’,” muses Jim White, “which I don’t agree with. ‘Serving the song’ is usually code for not getting in the way, but a lot of time you want to make a stand, you know?” For all his protestations, the Melbourne-born, New York-based drummer has been a crucial, dynamic part of countless excellent albums – from Cat Power, Smog and Bonnie “S‘Prince’ Billy, to his own work with the mighty instrumental trio Dirty Three, alongside Mick Turner and Bad Seed Warren Ellis. “A lot of these things were done very quickly,” White explains. “Some people like you to have the songs before, and sometimes they like you to do it on the spot. It’s always a battle playing the drums, too – generally, if it feels good, that’s the version.” For the last few years, White’s main interest has been Xylouris White, his ferocious duo with Cretan lute player and singer George Xylouris; their third album, Mother, is out in January. “George is as into improvising as I am,” says the drummer. “Through playing with him I feel like I’ve learnt a lot With Warren Ellis about the nature of what might be called improvisation, which turns out to (left) and Mick be more of a continuum of music.” Turner (right) TOM PINNOCK in “impatient” instrumental trio Dirty Three, 2005 VENOM P STINGER songs – like, the hearing that sound from the car. -

Exploring Cross-Gender Cover Songs of the Rolling Stones’

COVERING THE TRACKS: EXPLORING CROSS-GENDER COVER SONGS OF THE ROLLING STONES’ “SATISFACTION” by STEPHANIE DELANE DOKTOR (Under the Direction of Susan Thomas) ABSTRACT The 1965 Rolling Stones’ hit, “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” epitomizes domineering masculinity and aggressive sexuality. Saturated with unrelenting rhythms, emphatic vocal delivery, cocky and phallocentric lyrics, musical climaxes, and abrasive guitar timbres, “Satisfaction” has been regarded by many scholars and music critics as the anthem of the cock rock genre—a music representative of male power and domination. Yet despite the song’s association with a particular type of (white) male-identified, virile (hetero)sexuality, it has been covered by a variety of musicians of different races, genders, and sexualities. This thesis explores three cross-gender covers of “Satisfaction” recorded and performed by PJ Harvey and Björk (duet, 1994), Britney Spears (2000), and Cat Power (2000). Using theories of intertextuality, this project examines the ways in which all three musicians manipulate and subvert the dominant paradigms of the original song. INDEX WORDS: Cover songs, Gender, Intertextuality, Cross gender, The Rolling Stones, PJ Harvey, Björk, Britney Spears, Cat Power, (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction COVERING THE TRACKS: EXPLORING CROSS-GENDER COVER SONGS OF THE ROLLING STONES’ “SATISFACTION” by STEPHANIE DELANE DOKTOR B.A., North Georgia College and State University, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 © 2008 Stephanie DeLane Doktor All Rights Reserved COVERING THE TRACKS: EXPLORING CROSS-GENDER COVERS OF THE ROLLING STONES’ “SATISFACTION” by STEPHANIE DELANE DOKTOR Major Professor: Susan Thomas Committee: Adrian Childs Jean Kidula Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2008 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members—Dr.