Exploring Cross-Gender Cover Songs of the Rolling Stones’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aretha Franklin's Gendered Re-Authoring of Otis Redding's

Popular Music (2014) Volume 33/2. © Cambridge University Press 2014, pp. 185–207 doi:10.1017/S0261143014000270 ‘Find out what it means to me’: Aretha Franklin’s gendered re-authoring of Otis Redding’s ‘Respect’ VICTORIA MALAWEY Music Department, Macalester College, 1600 Grand Avenue, Saint Paul, MN 55105, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In her re-authoring of Otis Redding’s ‘Respect’, Aretha Franklin’s seminal 1967 recording features striking changes to melodic content, vocal delivery, lyrics and form. Musical analysis and transcription reveal Franklin’s re-authoring techniques, which relate to rhetorical strategies of motivated rewriting, talking texts and call-and-response introduced by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The extent of her re-authoring grants her status as owner of the song and results in a new sonic experience that can be clearly related to the cultural work the song has performed over the past 45 years. Multiple social movements claimed Franklin’s ‘Respect’ as their anthem, and her version more generally functioned as a song of empower- ment for those who have been marginalised, resulting in the song’s complex relationship with feminism. Franklin’s ‘Respect’ speaks dialogically with Redding’s version as an answer song that gives agency to a female perspective speaking within the language of soul music, which appealed to many audiences. Introduction Although Otis Redding wrote and recorded ‘Respect’ in 1965, Aretha Franklin stakes a claim of ownership by re-authoring the song in her famous 1967 recording. Her version features striking changes to the melodic content, vocal delivery, lyrics and form. -

DOSSIER DE PRESSE Me Phi S a D / © G R

PALOMA ET COME ON PEOPLE PRÉSENTENT 4 SCÈNES • PLUS de 50 GROUPES • ATELIERS DIY • JARDIN ÉPHÉMÈRE Fanny Lopez : me DOSSIER DE PRESSE s phi a r d / © G r a s s a l P ien t s a Séb : www.thisisnotalovesong.fr #TINALS © Illustration 1 MÉDIAS NATIONAUX MARTINGALE Jean-Philippe BERAUD [email protected] 01 43 73 48 77 / 06 12 81 26 52 Marilou ANDRIEU MÉDIAS RÉGIONAUX [email protected] 04 11 94 00 21 / 07 60 55 74 48 Anaïs GRUSON [email protected] 04 11 94 00 19 ESPACE http://thisisnotalovesong.fr/espace-pro-presse/ PRO-PRESSE Vous y trouverez les visuels de l’édition 2016, les photos des artistes ainsi que les communiqués et dossiers de presse en téléchargement. N’hésitez à pas demander un code d’accès à nos attachés de presse. 2 SOMMAIRE THIS IS NOT A LOVE SONG Avant-propos ....................................................................... 05 La programmation, jour par jour ........................................... 06 EN SAVOIR PLUS This is Not A love Song en quelques chiffres ........................ 09 Indie Music Festival ? ........................................................... 10 Do It Yourself ! ...................................................................... 12 Un amour de festival ............................................................ 15 Du soleil, mais pas que... ...................……………….............. 16 De l’international au local ...........................…….................. 16 Ils y étaient ........................................................................... 17 Les éditions -

A Concert Review by Christof Graf

Leonard Cohen`s Tower Of Song: A Grand Gala Of Excellence Without Compromise by Christof Graf A Memorial Tribute To Leonard Cohen Bell Centre, Montreal/ Canada, 6th November 2017 A concert review by Christof Graf Photos by: Christof Graf “The Leonard Cohen Memorial Tribute ‘began in a grand fashion,” wrote the MONTREAL GAZETTE. “One Year After His Death, the Legendary Singer-Songwriter is Remembered, Spectacularly, in Montral,” headlined the US-Edition of NEWSWEEK. The media spoke of a “Star-studded Montreal memorial concert which celebrated life and work of Leonard Cohen.” –“Cohen fans sing, shout Halleluja in tribute to poet, songwriter Leonard,” was the title chosen by THE STAR. The NATIONAL POST said: “Sting and other stars shine in fast-paced, touching Leonard Cohen tribute in Montreal.” Everyone present shared this opinion. It was a moving and fascinating event of the highest quality. The first visitors had already begun their pilgrimage to the Hockey Arena of the Bell Centre at noon. The organizers reported around 20.000 visitors in the evening. Some media outlets estimated 16.000, others 22.000. Many visitors came dressed in dark suits and fedora hats, an homage to Cohen’s “work attire.” Cohen last sported his signature wardrobe during his over three hour long concerts from 2008 to 2013. How many visitors were really there was irrelevant; the Bell Centre was filled to the rim. The “Tower Of Song- A Memorial Tribute To Leonard Cohen” was sold out. Expectations were high as fans of the Canadian Singer/Songwriter pilgrimmed from all over the world to Montreal to pay tribute to their deceased idol. -

It Might Just Be Ravens Writing in Mid-Air

FEATURE ARTICLE It Might Just Be Ravens Writing in Mid-Air DAVID W. JARDINE University of Calgary A Small Start And the children in the apple-tree Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea. T. S. Eliot, from Quartet No. 4, Section 5 of “Four Quartets” (lines 36–39) But then something about the sentence that followed stuck out. As a kid, I was just a kid. It sounds like a line from a Bill Callahan song. Is he saying, “Let’s leave that alone,” because there is something deeper he doesn’t want to discuss, or is it that there is really nothing there? Does it matter? Mark Richardson (2013, n.p.) from “A Window That Isn’t There: The Elusive Art of Bill Callahan” T MATTERS, but just how it matters and how much and to whom and to what end is not just a I tough call but a call that needs to be considered again and again, at every turn of circumstance. This is part of the sweet frustration of the interpretive life, that there is no single declaration. Stories get retold in the bury of the circumstances that call for them. And the pedagogical art of sensing that call is itself a practice, part of whose efficacy and worth is linked intimately to the very tale it considers. Thus, the places, the locales of consideration—with all their convoluted stories and memory and fantasy and desire and inhabitants—have something to say, here, too. -

August 2012 Newsletter

August 2012 Newsletter ------------------------------------ Yesterday & Today Records P.O.Box 54 Miranda NSW 2228 Phone: (02) 95311710 Email:[email protected] www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au ------------------------------------------------ Postage Australia post is essentially the world’s most expensive service. We aim to break even on postage and will use the best method to minimise costs. One good innovation is the introduction of the “POST PLUS” satchels, which replace the old red satchels and include a tracking number. Available in 3 sizes they are 500 grams ($7.50) 3kgs ($11.50) 5kgs ($14.50) P & P. The latter 2 are perfect for larger interstate packages as anything over 500 grams even is going to cost more than $11.50. We can take a cd out of a case to reduce costs. Basically 1 cd still $2. 2cds $3 and rest as they will fit. Again Australia Post have this ludicrous notion that if a package can fit through a certain slot on a card it goes as a letter whereas if it doesn’t it is classified as a “parcel” and can cost up to 5 times as much. One day I will send a letter to the Minister for Trade as their policies are distinctly prejudicial to commerce. Out here they make massive profits but offer a very poor number of services and charge top dollar for what they do provide. Still, the mail mostly always gets there. But until ssuch times as their local monopoly remains, things won’t be much different. ----------------------------------------------- For those long term customers and anyone receiving these newsletters for the first time we have several walk in sales per year, with the next being Saturday August 25th. -

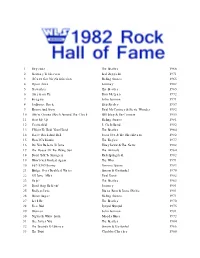

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Ar

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Arms Journey 1982 5 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 6 American Pie Don McLean 1972 7 Imagine John Lennon 1971 8 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 9 Ebony And Ivory Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder 1982 10 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 11 Start Me Up Rolling Stones 1981 12 Centerfold J. Geils Band 1982 13 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 14 I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett & The Blackhearts 1982 15 Hotel California The Eagles 1977 16 Do You Believe In Love Huey Lewis & The News 1982 17 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 18 Don't Talk To Strangers Rick Springfield 1982 19 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 20 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 1982 21 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel 1970 22 '65 Love Affair Paul Davis 1982 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 Don't Stop Believin' Journey 1981 25 Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Richie 1981 26 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 27 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 28 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 1975 29 Woman John Lennon 1981 30 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 31 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 32 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 33 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 34 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 35 Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 1981 36 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 37 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 38 California Dreamin' The Mamas & The Papas 1966 39 Lola The Kinks 1970 40 Lights Journey 1978 41 Proud -

Serra-Joan-Identification-Of-Versions

Identification of Versions of the Same Musical Composition by Processing Audio Descriptions Joan Serrà Julià TESI DOCTORAL UPF / 2011 Director de la tesi: Dr. Xavier Serra i Casals Dept. of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Copyright c Joan Serrà Julià, 2011. Dissertation submitted to the Deptartment of Information and Communica- tion Technologies of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR PER LA UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA, with the mention of European Doctor. Music Technology Group (http://mtg.upf.edu), Dept. of Information and Communica- tion Technologies (http://www.upf.edu/dtic), Universitat Pompeu Fabra (http://www. upf.edu), Barcelona, Spain. Als meus avis. Acknowledgements I remember I was quite shocked when, one of the very first times I went to the MTG, Perfecto Herrera suggested that I work on the automatic identification of versions of musical pieces. I had played versions (both amateur and pro- fessionally) since I was 13 but, although being familiar with many MIR tasks, I had never thought of version identification before. Furthermore, how could they (the MTG people) know that I played song versions? I don’t think I had told them anything about this aspect... Before that meeting with Perfe, I had discussed a few research topics with Xavier Serra and, after he gave me feedback on a number of research proposals I had, I decided to submit one related to the exploitation of the temporal information of music descriptors for music similarity. Therefore, when Perfe suggested the topic of version identification I initially thought that such a suggestion was not related to my proposal at all. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1963, Volume 58, Issue No. 2

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. 58, No. 2 JUNE, 1963 CONTENTS PAGE The Autobiographical Writings of Senator Arthur Pue Gorman John R. Lambert, Jr. 93 Jonathan Boucher: The Mind of an American Loyalist Philip Evanson 123 Civil War Memoirs of the First Maryland Cavalry, C. S.A Edited hy Samuel H. Miller 137 Sidelights 173 Dr. James B. Stansbury Frank F. White, Jr. Reviews of Recent Books 175 Bohner, John Pendleton Kennedy, by J. Gilman D'Arcy Paul Keefer, Baltimore's Music, by Lester S. Levy Miner, William Goddard, Newspaperman, by David C. Skaggs Pease, ed.. The Progressive Years, by J. Joseph Huthmacher Osborne, ed., Swallow Barn, by Cecil D. Eby Carroll, Joseph Nichols and the Nicholites, by Theodore H. Mattheis Turner, William Plumer of New Hampshire, by Frank Otto Gatell Timberlake, Prohibition and the Progressive Movement, by Dorothy M. Brown Brewington, Chesapeake Bay Log Canoes and Bugeyes, by Richard H. Randall Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan, Revolutionary Rifleman, by Frank F. White, Jr. de Valinger, ed., and comp., A Calendar of Ridgely Family Letters, by George Valentine Massey, II Klein, ed.. Just South of Gettysburg, by Harold R. Manakee Notes and Queries 190 Contributors 192 Annual Subscription to the Magazine, t'f.OO. Each issue $1.00. The Magazine assumes no responsibility for statements or opinions expressed in its pages. Richard Walsh, Editor C. A. Porter Hopkins, Asst. Editor Published quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society, 201 W. Monument Street, Baltimore 1, Md. Second-class postage paid at Baltimore, Md. > AAA;) 1 -i4.J,J.A.l,J..I.AJ.J.J LJ.XAJ.AJ;4.J..<.4.AJ.J.*4.A4.AA4.4..tJ.AA4.AA.<.4.44-4" - "*" ' ^O^ SALE HISTORICAL MAP OF ST. -

Punk Aesthetics in Independent "New Folk", 1990-2008

PUNK AESTHETICS IN INDEPENDENT "NEW FOLK", 1990-2008 John Encarnacao Student No. 10388041 Master of Arts in Humanities and Social Sciences University of Technology, Sydney 2009 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Tony Mitchell for his suggestions for reading towards this thesis (particularly for pointing me towards Webb) and for his reading of, and feedback on, various drafts and nascent versions presented at conferences. Collin Chua was also very helpful during a period when Tony was on leave; thank you, Collin. Tony Mitchell and Kim Poole read the final draft of the thesis and provided some valuable and timely feedback. Cheers. Ian Collinson, Michelle Phillipov and Diana Springford each recommended readings; Zac Dadic sent some hard to find recordings to me from interstate; Andrew Khedoori offered me a show at 2SER-FM, where I learnt about some of the artists in this study, and where I had the good fortune to interview Dawn McCarthy; and Brendan Smyly and Diana Blom are valued colleagues of mine at University of Western Sydney who have consistently been up for robust discussions of research matters. Many thanks to you all. My friend Stephen Creswell’s amazing record collection has been readily available to me and has proved an invaluable resource. A hearty thanks! And most significant has been the support of my partner Zoë. Thanks and love to you for the many ways you helped to create a space where this research might take place. John Encarnacao 18 March 2009 iii Table of Contents Abstract vi I: Introduction 1 Frames -

Foghat in the Studio: Fool for the City Mp3, Flac, Wma

Foghat In The Studio: Fool For The City mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Non Music Album: In The Studio: Fool For The City Country: US Released: 1991 Style: Blues Rock, Classic Rock, Radioplay, Spoken Word MP3 version RAR size: 1782 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1917 mb WMA version RAR size: 1114 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 539 Other Formats: MMF DMF AHX AAC AUD DTS AC3 Tracklist 1 Segment One 19:03 2 Segment Two 19:31 3 Segment Three 20:30 4 Segment Four 0:53 Companies, etc. Record Company – Bullet Productions Made By – Discovery Systems Notes Show number 148 for the air week of April 22, 1991. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Mirrored): MADE BY DISCOVERY SYSTEMS - AN AMERICAN COMPANY A2YE0100A Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Fool For The City (LP, BR 6959 Foghat Bearsville BR 6959 US 1975 Album) Fool For The City (CD, Rhino Records , 8122-70882-2 Foghat 8122-70882-2 Europe Unknown Album, RE, RM) Bearsville Fool For The City (Cass, BEA M5 6959 Foghat Bearsville BEA M5 6959 US 1975 Album) Fool For The City (LP, BRK 6980 Foghat Bearsville BRK 6980 US 1975 Album, Gol) Warner Bros. Fool For The City (LP, 3-01-404-086 Foghat Records, 3-01-404-086 Brazil 1977 Album) Bearsville Related Music albums to In The Studio: Fool For The City by Foghat Foghat - Energized Foghat - The Best Of Foghat Foghat - Drivin' Wheel Foghat - Stone Blue Foghat - Live Little Feat - In The Studio: "Waiting For Columbus" Foghat - I Just Want To Make Love To You Foghat - Fool For The City Foghat - Night Shift Foghat - Stranger In My Home Town. -

Universal Music Group's Profit Margins Grew in 2020, Despite

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 3, 2021 Page 1 of 31 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Universal Music Group’s Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No.Profit 1 on Billboard’s lion audienceMargins impressions, up 16%).Grew Top• Country TuneCore Albums Unveils chart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earnedRewards 46,000 Program equivalent album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingas Indie to Nielsen Distributors Music/MRC Data. in 2020, Despiteand total Country Airplay No.Pandemic 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideFend Off marks Major Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartLabels: and fourth Exclusive top 10. It follows freshman LP BY ED CHRISTMAN Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- Montevallo, which arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He • David Crosby Sells vember 2014 and reigned for nineEven weeks. in Toa nearly date, year-long economic downturn, the hit 1.487 billionfollowed euros with ($1.68 the multiweek billion), orNo. a 1s20% “In Casemargin. -

Acoustic Guitar

794 ACOUSTICACOUSTIC GUITARGUITAR ACOUSTIC THE ACOUSTIC INCLUDES THE NEW TAB NEW GUITAR GUITAR COMPLETE INCLUDES MAGAZINE’S PRIVATE METHOD, ACOUSTIC TAB LESSONS VOLUME 1 BOOK 2 GUITAR METHOD 24 IN-DEPTH LESSONS by David Hamburger LEARN TO PLAY USING String Letter Publishing String Letter Publishing THE TECHNIQUES & With this popular guide and Learn how to alternate the bass SONGS OF AMERICAN two-CD package, players will notes to a country backup ROOTS MUSIC learn everything from basic pattern, how to connect chords by David Hamburger techniques to more advanced with some classic bass runs, and String Letter Publishing moves. Articles include: Learning to Sight-Read (Charles how to play your first fingerpicking patterns. You’ll find out A complete collection of all three Acoustic Guitar Method Chapman); Using the Circle of Fifths (Dale Miller); what makes a major scale work and what blues notes do to books and CDs in one volume! Learn how to play guitar Hammer-ons and Pull-offs (Ken Perlman); Bass Line a melody, all while learning more notes on the fingerboard with the only beginning method based on traditional Basics (David Hamburger); Accompanying Yourself and more great songs from the American roots repertoire American music that teaches you authentic techniques and (Elizabeth Papapetrou); Bach for Flatpickers (Dix – especially from the blues tradition. Songs include: songs. Beginning with a few basic chords and strums, Bruce); Double-Stop Fiddle Licks (Glenn Weiser); Celtic Columbus Stockade Blues • Frankie and Johnny • The Girl you’ll start right in learning real music drawn from blues, Flatpicking (Dylan Schorer); Open-G Slide Fills (David I Left Behind Me • Way Downtown • and more.