The Dilemma of Edwin Arlington Robinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Membership Meeting

Niagara Frontier Bicycle Club, Inc. Volume XXIX NUMBER 7 OCTOBER 2007 General Membership Meeting Friday, October 19, 7:30 p.m. Amherst Community Church 77 Washington Parkway Parking and entrance behind church Food, Soft Drinks Annual Banquet November 16 2007 at Fox Valley Country Club The Can-ASmEE PA GCE 6e FOnR EtVEuNT rDETyAILS. Still HUGE! Thank You Mary Alice A bit wet — but what a great party! SEE INSIDE Date Time Map Miles Elev. Rating Ride Name Leader/Phone CREEK ROAD CANTER: E. Pembroke Central School, 6-Oct 10:00 719 33 1480 MD Rt 5, 4.75 miles East of Rt. 77. East Pembroke Lin Michalczak 674-3203 6-Oct OCTOBERFEST RIDE: Park & Ride, 10:00 239 48 4200 XD Rt 39 at end of 219 Expressway, Springville Ron Wakefield 877-2140 TRASH & TREASURE RIDE: Chestnut Ridge 7-Oct 10:00 273 30/23 Mod Park, Casino Lot, Rt 277, Orchard Park John Herman 675-1944 LANCASTER TO AKRON FALLS: Lancaster HS, 8-Oct 10:00 251 36 Easy Forton Dr @ Pleasantview Rd. Lancaster Darrell Skelton 634-6699 LOOSE GOOSE: Parking Lot @ Ronnie's Pizzeria on Rt. 16, 8-Oct 10:00 254 49/37 3200 XD/MD Holland, NY (0.1 miles before Holland Glenwood Road) Halli Lavner 655-0881 SKULPTURE PARK BIKE & HIKE: Griffis Sculpture 13-Oct 10:00 287 31/21 1200/700 Mod/Easy Park, Lower Lot on CR 75, Ashford Hollow, Rt. 219 Pat Danaher 838-0280 BECKER FARMS PUMPKIN FEST: Wide Waters 13-Oct 10:00 732 37 Easy Marina, Market Street & Cold Springs Rd., Lockport Tom Williams 688-2981 SPRINGVILLE SPRINT: Chestnut Ridge Park, 14-Oct 10:00 224 41/20 2750/1000 XD/MOD Casino Lot, Rt 277 Orchard Park Richard Swank 992-2404 WILLISTON ROAD RIDE: Como Park, 1st lot from 14-Oct 10:00 747 39/ 30 2000/1300 MD/ Mod Como Park Blvd entrance, Lancaster Brenda Fischer 683-3961 INDIAN FALLS LOG CABIN: Russell Town 20-Oct 10:00 705 37 Easy Park at Clinton St. -

Spike De Ates Lynnfield School Plan

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 2020 Spike de ates Lynn eld school plan Commercial By Anne Marie Tobin school as early as possible,” said School the district had originally planned to ITEM STAFF Committee Chairman Jamie Hayman. start the year with. Street to shut “I am disappointed for students, par- “We have been following and will con- LYNNFIELD — Due to a recent spike ents and teachers. This is not what any tinue to follow the data very closely. Our in the number of COVID cases, and the of us want.” biggest concern is that this is the rst discovery of two cases in school-age chil- down during “We want our kids back in schools, but time that school-age children have con- dren over the past 12 days, the Lynn eld we need to do right by them and act re- tracted the virus,” she said. “We have School Committee voted Wednesday to sponsibly,” said committee member Sta- 2,000 students and 1,000 staff to think of. suspend most in-school learning and piv- cy Dahlstedt. We need to do the right thing, and that is bridge repair ot to a fully remote plan through Sept. 30. Superintendent of Schools Kristen going with a remote learning model for “We are all reluctant ‘yesses’ (on the Vogel said she plans to continue moni- the rst two weeks of school,” adding that By Gayla Cawley vote) on this and I ask the communi- toring data trends in the hopes of being ITEM STAFF ty to do their best to get kids back in able to revert back to the hybrid model LYNNFIELD, A3 LYNN -— Commercial Street will be shut down to traf c for four weekends next year while the street’s commuter-rail bridge is being replaced. -

Page 1 UNIVERSITY of MASSACHUSETTS LOWELL

UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LOWELL COMPREHENSIVE PROFESSIONAL VITAE K A R E N D E V E R E A U X M E L I L L O , PhD, GNP, ANP-C, FAANP, FGSA Professor and Chair, Department of Nursing School of Health and Environment (978) 934-4417 EDUCATION AND ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS Education 1990 Ph.D. Brandeis University, Florence Heller School for Advanced Studies in Social Policy, Major Fields of Study: Aging, Long-Term Care, Health Policy; Waltham, MA, Dissertation: “Evaluation of Nursing Process and Outcomes of Care Utilizing Nurse Practitioners to Provide Health Care for Elderly Patients in Massachusetts Nursing Homes” 1978 M.S. University of Lowell, Gerontological Nursing, Preparation as a Gerontological Nurse Practitioner 1977 B.S.N. Salem State College, Nursing, Graduated Magna Cum Laude, GPA 3.74 1973 A.S. Massachusetts Bay Community College, Nursing, Graduated with High Honors Academic Experience June, 2005 to Present Professor and Chair, Department of Nursing University of Massachusetts Lowell September, 1993 Professor, Department of Nursing; to May, 2005 Coordinator, Gerontological Nursing Program, University of Massachusetts Lowell September, 1991 Associate Professor (Tenured) Department of Nursing to August, 1993 Coordinator, Gerontological Nursing Program, University of Massachusetts Lowell September, 1985 Assistant Professor, Department of Nursing to August, 1991 Coordinator, Gerontological Nursing Program, University of Lowell September, 1982 Instructor, on a Federal Grant, Gerontological to August, 1985 Nursing Program, University -

Rcy 072310 Main 007.Pdf

www.yankton.net Yankton Daily Press & Dakotan ■ Friday, July 23, 2010 PAGE 7B FRIDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT JULY 30, 2010 ARTS 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS From Page 2B Arthur Å WordGirl The Fetch! Cyber- Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Washing- Need to Know (N) (In McLaugh- Market to Dakota Last of the BBC World Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- America’s Ancient Ancient PBS (DVS) Å (DVS) Electric With Ruff chase Business Stereo) Å ton Week Stereo) Å lin Group Market Å Life “S.D. Summer News Stereo) Å ley Å Heartland History History KUSD ^ 8 ^ Company Ruffman Report (N) Å (N) Critters” Wine KTIV $ 4 $ Insider Extra (N) Ellen DeGeneres News (N) News News (N) Ent Friday Night Lights Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å News (N) Jay Leno Late Night Carson News Extra for more information on the Deal or No Deal or No Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT Two and a Friday Night Lights Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Last Call According Paid Pro- NBC Deal Å Deal Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Half Men Vince is persuaded to News With Jay Leno (N) (In Jimmy Fallon (N) (In With Car- to Jim Å gram Summer Pops Concert Series and KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å seek revenge. -

Pendragon © 2010 by Duncan Johnson the Moral Right of the Author Has Been Asserted

THE DOCTOR WHO PROJECT SEASON 37 1 THE DOCTOR WHO PROJECT SEASON 37 2 THE DOCTOR WHO PROJECT SEASON 37 Published by Jigsaw Publications/The Doctor Who Project Vancouver, BC, Canada First Published July 2010 Pendragon © 2010 by Duncan Johnson The moral right of the author has been asserted. Doctor Who © 1963, 2010 by BBC Worldwide The Doctor Who Project © & ™ 1999, 2010 by Jigsaw Publications A TDWP/Jigsaw Publications E-Book All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. All characters in this publication is fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely co-incidental. Typeset in Palatino Linotype Logo © 2005 The Doctor Who Project Cover © 2010 Kevin Mullen 3 THE DOCTOR WHO PROJECT SEASON 37 4 THE DOCTOR WHO PROJECT SEASON 37 Onboard the space-faring samara Ophrys , Harvester-Achene Pelles sheltered under the shattered husk of Pilot-Achene Bron. Heavy feet crunched across the samara's soft, organic interior and Pelles contracted his tendrils as much as possible, hoping that in the next life his friend would forgive him for hiding beneath his corpse. By rotating his photoreceptors, Pelles could see two pirates with him in the chamber. He had encountered nothing like them before - though admittedly this was his first flight away from the colony - and displayed a bafflingly small array of appendages. The pair seemed identical in every respect but for the contrasting colouration of their respective crowns. "Has the vessel been secured," the first, darker, pirate asked. -

04/01/2021 BPAC Agenda Packet

The BPAC Meeting will be held by teleconference – the public may access the meeting by calling the number below and entering the meeting ID when prompted. Phone number: 253 215 8782 Meeting ID: 883 5913 5225 Passcode: 282415 TOWN OF BASALT MEETINGS Basalt Public Arts Commission (BPAC) Thursday, April 1, 2021 101 Midland Avenue 6:00 PM Call to Order 6:02 Approval of Minutes 6:03 Refresher on meeting organization Discussion topics: • Making and seconding motions • Quorum • “Sunshine” laws and open meetings • Conflicts of interest and recusal 6:08 Review of Videographer Applications Discussion topics: • Procedure for selecting videographers: hear Staff recommendations. 6:30 Arts Master Plan Update: benchmark study portion of plan Discussion questions: 1. Susan and Watkins’s idea is to include as-is in the future Arts Master Plan as an appendix and use key elements in developing the Master Plan. Do you agree? 2. Does this seem like a complete and useful study? 3. Next steps discussion. Parts of study that are notable to Susan and Watkins (pages refer to document page numbers, in bottom right-hand corner): 1. Pages 5-8 – key findings 2. Pages 31, 39 about artist “rosters” 3. Page 19 about Boulder’s future lecture series 4. Staffing discussions: pages 38, 42, 44, 45, 64 5. Cost of arts master plans: pages 36, 58 7:10 Arts Collaborations Discussion questions: 1. What should be BPAC’s goals for collaborations in 2021? 2. Is BPAC comfortable with collaborations appearing similar to past years’ grant program, where organizations come forward with a financial ask? 3. -

A New Riding Season Is Upon Us and I Would Like to Begin by Thanking All

cancelled. Last year only one ride was cancelled for A new riding season is upon us and I would like to lack of a ride leader. begin by thanking all the people who make the rides possible. I’ll start with this year’s ride committee: You will also find a tentative list of the 2006 weekend Pat Danaher, Brenda Fischer, Jean Frederick, Lori and holiday rides. I’m sure we’ll find some problems Harf, Rebecca Ribis, Raymond Thomas, and Roy with it as the season goes on (closed roads, closed Tocha. Next are the people who have already bridges, closed parks …) and may need to make volunteered to lead rides this month and are listed in some changes. Take a look at it, let me know if you the March ride schedule. Lastly, I would like to thank see any problems, and remember to look in the all the people who will soon volunteer to lead the rest Spokesman each month for the most up to date of the rides (your name goes here). As in 2005, if a version of the schedule. And of course, the weekday ride has no leader when the newsletter goes to press morning and weekend rides continue as do the in the middle of the preceding month, the ride will be weekend breakfast rides. Tire pressure is one of the most controversial and or touring. Racers can go narrower and tourers should misunderstood elements of road riding. go wider. Most roadies are under the mistaken impression If your tire size corresponds to your weight, you can that unless pressure is well over 100 pounds per run 90-95 psi and not risk pinch flats. -

Dragons of War by Tracy and Laura Hickman

)~ gr v Sample file Sample ayce TM Official Game Adventure Dragons of War by Tracy and Laura Hickman TABLE OF CONTENTS Prologue 2 Wherein the Tale is told, and the story expounded thus far. The Knights of Solamnia 3 Wherein the Order of the Knights is rehearsed and their greatest weakness exposed. Chapter 10: Winter Councils 5 Wherein journeys across land and water to the heroes' destiny are recounted. Chapter 11: The Last Bastion 14 Wherein dark armies break like waves against battlements. The war is begun and the hand of destiny is set into motion. Chapter 12: The Tower 18 Wherein the heroes tread forbidden halls and find battle joined within. Epilogue 26 Wherein destinies are fulfilled and the shadows of fate lengthen. Appendices Sample file 27 Here are given supplements to the tale. The new and unusual are explained, as are encounters governed by fate alone. CREDITS Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Dis- tributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distfibutors. Distrib- Editor: Mike Breault uted in the United Kingdom by TSR UK Ltd. Cover Art: Keith Parkinson ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, AD&D, Interior Art: Diana Magnuson DRAGONLANCE, PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION, and the TSR logo are trademarks of TSR Inc. Cartography: David Sutherland III Typography: Linda Bakk This adventure is protected under the copyright laws of the United Keylining; Colleen O'Malley States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the Tom Darden material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of TSR Inc. -

Scholarworks@Umass Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 5-2009 The Role of Human and Social Capital in the Perpetuation of Leader Development Jeffrey W. Mott University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Sports Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mott, Jeffrey W., "The Role of Human and Social Capital in the Perpetuation of Leader Development" (2009). Open Access Dissertations. 67. https://doi.org/10.7275/jvh2-3n60 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/67 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROLE OF HUMAN AND SOCIAL CAPITAL IN THE PERPETUATION OF LEADER DEVELOPMENT A Doctoral Dissertation Presented by JEFFREY W. MOTT Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in fulfillment of the proposal requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2009 Sport Management © Copyright by Jeffrey William Mott 2009 All Rights Reserved THE ROLE OF HUMAN AND SOCIAL CAPITAL IN THE PERPETUATION OF LEADER DEVELOPMENT A Doctoral Dissertation Presented by JEFFREY W. MOTT Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________________ James Gladden, Committee Co-Chair ____________________________________________ Carol Barr, Committee Co-Chair ____________________________________________ Linda Griffin, Committee Member ____________________________________________ Charles Manz, Committee Member __________________________________________ Lisa Masteralexis, Department Head Sport Management DEDICATION To the greatest passions in my life, for their unconditional love and enduring support – my partner for life, Brenda, and my three greatest friends, Carly, Griffin, and Peyton. -

House Md English Subtitles Season 6

House md english subtitles season 6 click here to download House M.D.. Season 8 | Season 7 | Season 6 | Season 5 | Season 4 | Season 3 | Season 2 | Season 1. #, Episode, Amount, Subtitles. 6x21, Help Me, 11, en · es. Download House M.D. season 6 subtitles. english subtitles. filename: House_M.D. - season www.doorway.ru subtitles amount: subtitles list: House M.D. - 6x - www.doorway.ru House M.D. - 6x11 - Remorsep www.doorway.ru D. - season www.doorway.ru subtitles amount: subtitles list: House M.D. - 6x01 - www.doorway.ru House M.D. - 6x04 - Instant www.doorway.ru english - 57 , french - 46 , greek - 42 portuguese - 34 , portuguese(br) - 20 House M.D. - 6x12 - Moving the Chainsp www.doorway.ru English. · House M.D. - 6x20 - www.doorway.ru English. · House M.D. House M.D. - Season 6: In this season, House finds himself in an House M.D. - Season 6 Streaming Free. Watch Online House M.D. Season 6 HD with Subtitles House M.D. Online Streaming with english subtitles All Episodes HD Streaming eng sub Online HD. Greek subtitles for House M.D. Season 6 [S06] - The series follows the life of anti-social, pain English. House MD 6x19 - The Choice {HDTV XviD 2HD en}, get. «House, M.D.» – Season 6, Episode 19 watch in HD quality with subtitles in different languages for free and without registration! House M.D. - Season 6, House M.D. - Season 6 FULL free movies Online HD. Episode Broken (1) SERVER 10 An antisocial maverick. Watch House M.D. - Season 6, House M.D. - Season 6 Full free movies Online HD. -

Episode Guide

Last episode aired Monday May 21, 2012 Episodes 001–175 Episode Guide c www.fox.com c www.fox.com c 2012 www.tv.com c 2012 www.fox.com The summaries and recaps of all the House, MD episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on May 25, 2012 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.36 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 Paternity . .5 3 Occam’s Razor . .7 4 Maternity . .9 5 Damned If You Do . 11 6 The Socratic Method . 13 7 Fidelity . 15 8 Poison . 17 9 DNR ............................................... 19 10 Histories . 21 11 Detox . 23 12 Sports Medicine . 25 13 Cursed . 27 14 Control . 29 15 Mob Rules . 31 16 Heavy . 33 17 Role Model . 35 18 Babies & Bathwater . 37 19 Kids ............................................... 39 20 Love Hurts . 41 21 Three Stories . 43 22 Honeymoon . 47 Season 2 49 1 Acceptance . 51 2 Autopsy . 53 3 Humpty Dumpty . 55 4 TB or Not TB . 57 5 Daddy’s Boy . 59 6 Spin ............................................... 61 7 Hunting . 63 8 The Mistake . 65 9 Deception . 67 10 Failure to Communicate . 69 11 Need to Know . 71 12 Distractions . 73 13 Skin Deep . 75 14 Sex Kills . 77 15 Clueless . 79 16 Safe ............................................... 81 17 AllIn............................................... 83 18 Sleeping Dogs Lie . 85 19 House vs. God . 87 20 Euphoria (1) . 89 House, MD Episode Guide 21 Euphoria (2) . 91 22 Forever . -

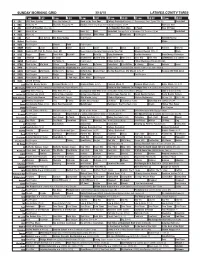

Sunday Morning Grid 3/15/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/15/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Road to the Final Four College Basketball Atlantic 10 Tournament, Final: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Detroit Red Wings at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 5 CW 2015 LA Marathon (N) (TVG) Å L.A. Marathon Post Show In Touch Hour Of Power 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Chicago Bulls at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Paid Program NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Program Movie 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Healing ADD With Dr. Daniel Amen, MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) Classical Rewind (TVG) Å Mága 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Aging Backwards Healthy Hormones BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly 10,000 B.C. ›› (2008) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B.