Scholarworks@Umass Amherst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

LSU Basketball Vs

THE BRADY ERA | In 10th YEAR, 6 POSTSEASON TOURN., 3 WESTERN DIV. and 2 SEC TITLES; 2006 FINAL 4 LSU Basketball vs. University of Connecticut January 6, 2007, 8 p.m. CST (LSU Sports Radio Network, ESPN) Pete Maravich Assembly Center -- Baton Rogue, La. LSU (10-3) Probable LSU Starters (based on the last game): G -- 2Dameon Mason (6-6, 183, Jr., Kansas City, Mo.) 8.0 ppg, 3.5 rpg, 1.2 apg NOVEMBER Mason started last four games, 11 in all this season ... Had 14, 13 and 11 points during the three games of the 9 E. A. Sports (Exh.) W, 70-65 HCF Classic ... 14 vs. Wright State (12/27) season est ... Out of starting lineup against Oregon State (12/17) 15 Louisiana College (Exh.) W, 94-41 and Washington (12/20) because of migraines ... Five total games scoring in double figures. 17 Nicholls State W, 96-42 19 Louisiana-Monroe (CST) W, 88-57 G -- 14 Garrett Temple (6-5, 190, So., Baton Rouge, La.) 10.2 ppg, 2.8 rpg, 4.1 apg 25 #24 Wichita State (CST) L, 53-57 Six games in double figures ... Had career highs of seven assists in back-to-back games of HCF Classic (Miss. 29 McNeese State (CST) W, 91-57 Valley, 12/28; Samford 12/29) with just five combined turnovers ... In first seven games had 23 assists and just DECEMBER 7 turnovers ... Career high of 18 at Tulane (12/2) with 17 vs. McNeese (11/29) and at Oregon State (12/17) ... 2 At Tulane (1) W, 74-67 Earned reputation as defensive stopper after holding Duke’s J.J. -

2020-21 COLORADO BASKETBALL Colorado Buffaloes Coaches Year-By-Year Conference Overall Season Conf

colorado buffaloes Coaching Records COLORADO COACHING CHRONOLOGY No. Coach Years Coached Seasons Won Lost Percent no coach ..................................................................1902-1906 5 18 15 .545 1. Frank R. Castleman ..................................................1907-1912 6 32 22 .592 2. John McFadden ........................................................1913-1914 2 10 9 .526 3. James N. Ashmore ...................................................1915-1917 3 16 10 .615 4. Melbourne C. Evans ..................................................1918 1 9 2 .818 5. Joe Mills ..................................................................1919-1924 6 30 24 .556 6. Howard Beresford ....................................................1925-1933 9 76 52 .594 7. Henry P. Iba ............................................................1934 1 9 8 .529 8. Earl “Dutch” Clark ....................................................1935 1 3 9 .250 9. Forrest B. Cox ..........................................................1936-1950 13 147 89 .623 10. H. B. Lee..................................................................1950-1956 6 63 74 .459 11. Russell “Sox” Walseth ..............................................1956-1976 20 261 245 .516 12. Bill Blair ..................................................................1976-1981 5 67 69 .493 13. Tom Apke ................................................................1981-1986 5 59 81 .421 14. Tom Miller ...............................................................1986-1990 4 35 -

2006 Media Guide.Indd

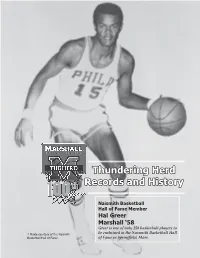

TThunderinghundering HerdHerd RRecordsecords aandnd HHistoryistory Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame Member Hal Greer Marshall ‘58 Greer is one of only 258 basketball players to * Photo courtesy of the Naismith be enshrined in the Naismith Basketball Hall Basketball Hall of Fame. of Fame in Springfi eld, Mass. 9977 r “Consistency,” Hal Hal Greer was named one of the NBA’s Top e Greer once told the e 50 Players in the late 90’s. He averaged 19 r Philadelphia Daily points, fi ve rebounds, and four assists in his G News. “For me, that was l NBA career. a the thing … I would like H Hal Greer to be remembered as a great, consistent player.” Over the course of rebounds and 4.4 assists per contest. With injuries limiting the 15 NBA seasons Schayes to 56 games, Greer took over the team’s scoring turned in by the slight, mantle. He ranked 13th in the NBA in scoring and ninth soft -spoken Hall of in free-throw percentage (.819). In the 1962 NBA All-Star Fame guard from West Game, Greer racked up a team-high nine assists - one more Virginia, consistency than the legendary Bob Cousy - and hauled in 10 rebounds, was indeed the thing. just two fewer than another legend, Bill Russell. Greer led He turned in quality the Nationals to the playoff s, where they fell to Warriors in performances almost every night, scoring 19.2 points the Eastern Division Semifi nals. per game during his career, playing in 1,122 games, and The smooth guard broke into the ranks of the top 10 racking up 21,586 points (14th on the all-time list). -

Arizona State University

S B M 2 0 U A 1 E 8 N - S N 1 9 K ’ D S E E T V B I L A L L DE'QUON LAKE, SR / ROMELLO WHITE, SO / REMY MARTIN, SO 2018-19 SUN DEVIL BASKETBALL Coach Bobby Hurley and his staff have played non-conference games against some of the best in college basketball and has proven it is not afraid to go on the road. Expect the effort to schedule the best to continue. SUN DEVIL TEAMS PLAYED OR TO BE PLAYED SINCE HIRING OF BOBBY HURLEY Creighton (Big East) Marquette (Big East) St. John’s (Big East) Georgia (SEC) Mississippi State (SEC) Texas A&M (Big 12) Kansas (Big 12) NC State (ACC) UNLV (MWC) Kansas State (Big 12) Purdue (Big 10) Vanderbilt (SEC) Kentucky (SEC) San Diego State (MWC) Xavier (Big East) 2016-17 @SunDevilHoops Media Information 2018-19 SUN DEVIL BASKETBALL table OF contents Table of Contents, Credits ...........................................................1 Bobby Hurley .........................................................................26-27 Schedule ..........................................................................................2 Drazen Zlovaric ............................................................................ 29 Rosters and Pronunciations ........................................................3 Rashon Burno ........................................................................30-31 Radio and TV Roster/Headshots ...............................................4 Anthony Coleman........................................................................ 32 Bob Hurley Facts ...........................................................................5 -

Special Edition 1 (PDF)

XAVIER BASKETBALL – NEWSLETTER S.E. February 5, 2006 Follow Me By MICHAEL SOKOLOVE Ethics exemplar. And soon to become, in marketing terms, "the Michael Jordan of college coaches," according to his agent, David Falk (who is, yes, Jordan's agent). Krzyzewski (pronounced sha-SHEF-ski) has been doing about 30 corporate speaking gigs a year for about $50,000 a pop. (He plans to cut back on the number of speeches while raising his fee to $100,000.) He is host of an annual conference at Duke's Fuqua School of Business. The university, in an unusual move, put its basketball coach's name on an academic center, the Fuqua/Coach K Center of Leadership & Ethics, and made Krzyzewski an "executive in residence" with the expectation that he will be able to become a professor whenever he stops coaching. In addition, Duke Corporate Education, which consults to businesses, has developed a program that uses Krzyzewski's methods as a teaching tool. PricewaterhouseCoopers has so far sent about 500 senior associates and managers — most of them "partners in the making," as they were described to me — to study Duke basketball in a "metaphoric context" to help them reach personal and professional goals. That irritating American Express commercial is blaring All of this is easy to ridicule because Krzyzewski is, again during the college basketball telecasts. The after all, a mere coach — and in some quarters, scrappy Polish guy from Chicago is standing in front of especially among rival fans in the bitterly competitive his bench, his feet firmly planted on the holy hardwood Atlantic Coast Conference, a reviled one. -

Cosida E-Digest August 2014 • 1 Cosida E-Digest August 2014 • 2 Cosida E-Digest August 2014 • 3 Cosida E-Digest August 2014 • 4 2014 Cosida AUGUST E-DIGEST

CoSIDA E-Digest August 2014 • 1 CoSIDA E-Digest August 2014 • 2 CoSIDA E-Digest August 2014 • 3 CoSIDA E-Digest August 2014 • 4 2014 CoSIDA AUGUST E-DIGEST Supporting CoSIDA > • ASAP Sports .......................................48 • Capital One ...........................................2 • CBS Sports Network/Stat Crew.........42 • College Football Playoff ....................42 • CoSIDA’s “Service Providers” ..........34 Table of Contents . • ESPN ...................................................12 2014-15 CoSIDA Board & Staff ........................................................................ 6-7 2014 CoSIDA Convention Photo Gallery ........................................................ 8-31 • Heisman Trophy .................................38 Capital One Academic All-America® • Learfield Sports ....................................4 Academic All-American of the Year Videos .............................................. 32-33 Jim Seavey Named Massassachusetts Maritime Employee of the Year ........... 35 • NCAA .....................................................3 Bob Vazquez Retires After 37 Years in Media Relations ................................... 36 • NewTek ..................................................4 Annual Membership and Convention Totals ...................................................... 37 Bill Morgal and Shawn Medeiros Honored by USTFCCCA ............................... 39 • NBA ......................................................42 LSU’s Will Stafford Honored by USTFCCCA .................................................... -

Men's Basketball Decade Info 1910 Marshall Series Began 1912-13

Men’s Basketball Decade Info 1910 Marshall series began 1912-13 Beckleheimer NOTE Beckleheimer was a three sport letterwinner at Morris Harvey College. Possibly the first in school history. 1913-14 5-3 Wesley Alderman ROSTER C. Fulton, Taylor, B. Fulton, Jack Latterner, Beckelheimer, Bolden, Coon HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Played Marshall, (19-42). NOTE According to the 1914 Yearbook: “Latterner best basketball man in the state” PHOTO Team photo: 1914 Yearbook, pg. 107 flickr.com UC sports archives 1917-18 8-2 Herman Beckleheimer ROSTER Golden Land, Walter Walker HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Swept Marshall 1918-19 ROSTER Watson Haws, Rollin Withrow, Golden Land, Walter Walker 1919-20 11-10 W.W. Lovell ROSTER Watson Haws 188 points Golden Land Hollis Westfall Harvey Fife Rollin Withrow Jones, Cano, Hansford, Lambert, Lantz, Thompson, Bivins NOTE Played first full college schedule. (Previous to this season, opponents were a mix from colleges, high schools and independent teams.) 1920-21 8-4 E.M. “Brownie” Fulton ROSTER Land, Watson Haws, Lantz, Arthur Rezzonico, Hollis Westfall, Coon HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Won two out of three vs. Marshall, (25-21, 33-16, 21-29) 1921-22 5-9 Beckleheimer ROSTER Watson Haws, Lantz, Coon, Fife, Plymale, Hollis Westfall, Shannon, Sayre, Delaney HIGHLIGHTED OPPONENT Played Virginia Tech, (22-34) PHOTO Team photo: The Lamp, May 1972, pg. 7 Watson Haws: The Lamp, May 1972, front cover 1922-23 4-11 Beckleheimer ROSTER H.C. Lantz, Westfall, Rezzonico, Leman, Hager, Delaney, Chard, Jones, Green. PHOTO Team photo: 1923 Yearbook, pg. 107 Individual photos: 1923 Yearbook, pg. 109 1923-24 ROSTER Lantz, Rezzonico, Hager, King, Chard, Chapman NOTE West Virginia Conference first year, Morris Harvey College one of three charter members. -

Coaching Staff Coaching Staff Head Coach Lorenzo Romar

HuskiesCoaching Staff Coaching Staff Head Coach Lorenzo Romar Washington men’s ship and finish 31-2. Cameron Dollar, an assistant • Saint Louis won their first conference tourna- basketball coach coach on Romar’s Saint Louis and Washington ment championship in the program’s history. Lorenzo Romar was staffs, was one of the stars for the Bruins during named to head up that national title contest, replacing injured point • The Billikens became the first No. 9 seed to the program at his guard Tyus Edney in the starting lineup. win the Conference USA Tournament. alma mater on April Romar built a reputation as one of the nation’s top • Saint Louis upset a No. 1 team, Cincinnati, for 3, 2002. A point recruiters while an assistant at UCLA (1992-1996) the first time since the 1951-52 season when guard for the Hus- and was credited with recruiting much of the talent the Bills knocked off top-ranked Kentucky. kies’ 1978-79 and that formed the core of the Bruins’ title team. 1979-80 teams, • The Billikens won the first Bud Light Show- Romar is the 18th In three years at Saint Louis, Romar compiled a down by knocking off intrastate rival Missouri head coach in 51-44 (.537) record, including victories over nine for the first time since the 1970-71 season. Washington’s 101- different conference champions. His 51 wins rank After reaching the NCAA Tournament in his first year history. He is the first African-American No. 7 among all-time SLU coaches and is the season, expectations were high for Romar’s 2000- coach to lead the Washington basketball program. -

Volume 11 Number 5.Indd

Volume 11 Number 5 February 2005 It’s Just Man-to-Man In Disguise by Neil W. Gabbey So if your team is facing a I could have told him what my good zone defense, how do you middle school players were doing Back when I was coaching attack it? to beat the same kind of zone. the middle school team at Gilman, The short answer: run your I taught my players as many as man half-court sets. The other The longer answer: keep fi ve zone defenses that we would night, I watched the end of the reading. rotate each time the opposition Princeton-Temple game – which Our current varsity team dribbled down court. And while turned into John Chaney’s 1000th my primary reason for doing this runs no half-court set “plays.” We win, courtesy of an unmade goal- run a primary break and then set was to take advantage of my play- tending call. Ah, home cookin’! ers’ intelligence and athleticism up in a 1-4, if nothing else pres- Mike Jarvis provided color com- ents itself immediately. We stress — not to mention keeping the oth- mentary, and he admitted that er teams constantly guessing — I ball movement and player move- it took him a few losses against ment. knew all along that all we were Coach Chaney’s vaunted match- doing was playing fundamentally But because we aim to play up zone before he realized that the an up-tempo game, hoping to gen- sound man-to-man. best way to attack it was to run Each time I teach a new erate turnovers and easy transi- man-to-man plays. -

The Tournament

The Tournament Tournament Records .................................. 2 Tournament History Facts ........................ 9 Annual Individual Leaders ....................... 10 Tournament Seeds History ...................... 15 Yearly Totals .................................................... 22 Conference Won-Lost Records ............... 25 Tournament Field by State ...................... 31 Televised College Basketball Games ... 32 Financial Analysis ......................................... 33 Tournament Facts ........................................ 34 Team-By-Team Won-Lost Records ........ 39 2 TOURNAMENT RECORDS—INDIVIDUAL GAME Tournament Records A national championship game is indicated by (CH), national 20, Austin Carr, Notre Dame vs. TCU, 1st R, 3-13- 17, Johnny Miller, Temple vs. Cincinnati, 1st R, 3-16- semifinal game by (NSF), national third-place game by (N3d), 1971 1995 regional final game by (RF), regional semifinal game by (RSF), FIELD GOALS ATTEMPTED 17, Shawn Respert, Michigan St. vs. Weber St., 1st R, regional third-place game by (R3d), second-round game by (2d 44, Austin Carr, Notre Dame vs. Ohio, 1st R, 3-7-1970 3-17-1995 R), first-round game by (1st R), opening-round game by (OR), 42, Lennie Rosenbluth, North Carolina vs. Michigan 17, Dedric Willoughby, Iowa St. vs. UCLA, RSF, 3-20- and later vacated by (*). St., NSF, 3-22-1957 (3 ot) 1997 (ot) 40, Austin Carr, Notre Dame vs. Houston, R3d, 3-20- 17, Kirk Hinrich, Kansas vs. Arizona, RF, 3-29-2003 Individual Game 1971 17, Taquan Dean, Louisville vs. West Virginia, RF, 39, Austin Carr, Notre Dame vs. Iowa, R3d, 3-14- 3-26-2005 1970 17, Drew Neitzel, Michigan St. vs. North Carolina, 2d POINTS 38, Bob Cousy, Holy Cross vs. North Carolina St., RF, R, 3-17-2007 61, Austin Carr, Notre Dame vs. -

Oklahoma State Cowboys

Oklahoma State Cowboys UNIVERSITY FACTS 2014-15 SCHEDULE TEAM NOTEBOOK Location ............................................. Stillwater, Oklahoma November Founded ....................................................................... 1890 Oklahoma State has had at least 20 wins in 19 of 8 Missouri Western {Exh.} 2:00 p.m. 14 Southeastern Louisiana 7:00 p.m. the last 24 years, including five times in six seasons Enrollment .................................................................35,214 16 Prairie View A&M 2:00 p.m. under coach Travis Ford. Thirteen of OSU’s 18 Northwestern (Okla.) State 7:00 p.m. Nickname ............................................................. Cowboys victories in 2013-14 were by 15 points or more. 21 Milwaukee 7:00 p.m. Colors......................................................Orange and Black MGM Grand Main Event, Las Vegas, Nev. 24 vs. Oregon State (ESPN3) 7:30 p.m. Website ............................................................ okstate.com Junior guard Phil Forte has had double-figure 26 vs. Auburn or Tulsa (ESPN2 or ESPN3) 8/10:30 p.m. point totals in nine of his last 10 games, including Twitter................................................................@OSUMBB 20 points or more four times. He has shot 40.5 December Arena (Capacity) ..................Gallagher-Iba Arena (13,611) percent from 3-point range during that stretch with 3 North Texas 7:00 p.m. SEC-Big 12 Challenge President ........................................................Burns Hargis 19 assists and just four turnovers. 6 at South Carolina (ESPNU) 11:00 a.m. Director of Athletics ....................................... Mike Holder 13 at Memphis (ESPN2) 5:00 p.m. Senior Le’Bryan Nash ranks 21st on the OSU career 16 Middle Tennessee State (ESPNU) 8:00 p.m. Faculty Athletics Representative. ........Dr. Meredith Hamilton scoring list with 1,307 points after three seasons. 21 Maryland (ESPNU) 1:00 p.m.