Interspecific Evaluation of Octopus Escape Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Monitoring of Eelgrass Resources in Newport Bay Newport Beach, California

MARINE TAXONOMIC SERVICES, LTD 2020 Monitoring of Eelgrass Resources in Newport Bay Newport Beach, California December 25, 2020 Prepared For: City of Newport Beach Public Works Department 100 Civic Center Drive, Newport Beach, CA 92660 Contact: Chris Miller, Public Works Manager [email protected], (949) 644-3043 Newport Harbor Shallow-Water and Deep-Water Eelgrass Survey Prepared By: MARINE TAXONOMIC SERVICES, LLC COASTAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT, INC 920 RANCHEROS DRIVE, STE F-1 23 Morning Wood Drive SAN MARCOS, CA 92069 Laguna Niguel, CA 92677 2020 NEWPORT BAY EELGRASS RESOURCES REPORT Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................................................ ii Appendices .................................................................................................................................................................. iii Abbreviations ...............................................................................................................................................................iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Project Purpose .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................... -

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Life History, Mating Behavior, and Multiple Paternity in Octopus

LIFE HISTORY, MATING BEHAVIOR, AND MULTIPLE PATERNITY IN OCTOPUS OLIVERI (BERRY, 1914) (CEPHALOPODA: OCTOPODIDAE) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI´I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ZOOLOGY DECEMBER 2014 By Heather Anne Ylitalo-Ward Dissertation Committee: Les Watling, Chairperson Rob Toonen James Wood Tom Oliver Jeff Drazen Chuck Birkeland Keywords: Cephalopod, Octopus, Sexual Selection, Multiple Paternity, Mating DEDICATION To my family, I would not have been able to do this without your unending support and love. Thank you for always believing in me. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all of the people who helped me collect the specimens for this study, braving the rocks and the waves in the middle of the night: Leigh Ann Boswell, Shannon Evers, and Steffiny Nelson, you were the hard core tako hunters. I am eternally grateful that you sacrificed your evenings to the octopus gods. Also, thank you to David Harrington (best bucket boy), Bert Tanigutchi, Melanie Hutchinson, Christine Ambrosino, Mark Royer, Chelsea Szydlowski, Ily Iglesias, Katherine Livins, James Wood, Seth Ylitalo-Ward, Jessica Watts, and Steven Zubler. This dissertation would not have happened without the support of my wonderful advisor, Dr. Les Watling. Even though I know he wanted me to study a different kind of “octo” (octocoral), I am so thankful he let me follow my foolish passion for cephalopod sexual selection. Also, he provided me with the opportunity to ride in a submersible, which was one of the most magical moments of my graduate career. -

Husbandry Manual for BLUE-RINGED OCTOPUS Hapalochlaena Lunulata (Mollusca: Octopodidae)

Husbandry Manual for BLUE-RINGED OCTOPUS Hapalochlaena lunulata (Mollusca: Octopodidae) Date By From Version 2005 Leanne Hayter Ultimo TAFE v 1 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1 PREFACE ................................................................................................................................ 5 2 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 CLASSIFICATION .............................................................................................................................. 8 2.2 GENERAL FEATURES ....................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 HISTORY IN CAPTIVITY ..................................................................................................................... 9 2.4 EDUCATION ..................................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 CONSERVATION & RESEARCH ........................................................................................................ 10 3 TAXONOMY ............................................................................................................................12 3.1 NOMENCLATURE ........................................................................................................................... 12 3.2 OTHER SPECIES ........................................................................................................................... -

Kelp Forest Monitoring Handbook — Volume 1: Sampling Protocol

KELP FOREST MONITORING HANDBOOK VOLUME 1: SAMPLING PROTOCOL CHANNEL ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK KELP FOREST MONITORING HANDBOOK VOLUME 1: SAMPLING PROTOCOL Channel Islands National Park Gary E. Davis David J. Kushner Jennifer M. Mondragon Jeff E. Mondragon Derek Lerma Daniel V. Richards National Park Service Channel Islands National Park 1901 Spinnaker Drive Ventura, California 93001 November 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1 MONITORING DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS ......................................................... Species Selection ...........................................................................................2 Site Selection .................................................................................................3 Sampling Technique Selection .......................................................................3 SAMPLING METHOD PROTOCOL......................................................................... General Information .......................................................................................8 1 m Quadrats ..................................................................................................9 5 m Quadrats ..................................................................................................11 Band Transects ...............................................................................................13 Random Point Contacts ..................................................................................15 -

Recognizing Cephalopod Boreholes in Shells and the Northward Spread of Octopus Vulgaris Cuvier, 1797 (Cephalopoda, Octopodoidea)

Vita Malacologica 13: 53-56 20 December 2015 Recognizing cephalopod boreholes in shells and the northward spread of Octopus vulgaris Cuvier, 1797 (Cephalopoda, Octopodoidea) Auke-Florian HIEMSTRA Middelstegracht 20B, 2312 TW Leiden, The Netherlands email: [email protected] Key words: Cephalopods, Octopus , predation, hole-boring, The Netherlands ABSTRACT & Arnold, 1969; Wodinsky, 1969; Hartwick et al., 1978; Boyle & Knobloch, 1981; Cortez et al., 1998; Steer & Octopuses prey on molluscs by boring through their shell. Semmens, 2003; Anderson et al., 2008; for taxonomical Among the regular naticid borings, traces of cephalopod pre - updates see Norman & Hochberg, 2005). However, the habit dation should be found soon on Dutch beaches. Bottom trawl - of drilling may prove to be more widespread within octopods ing has declined, and by the effects of global warming since only few species have actually been investigated Octopus will find its way back to the North Sea where it lived (Bromley, 1993). Drilled holes were found in polypla - before. I describe the distinguishing characters for Octopus cophoran, gastropod and bivalve mollusc shells, Nautilus and bore holes, give an introduction into this type of behaviour, crustacean carapaces (Tucker & Mapes, 1978; Saunders et al., present a short history of Dutch octopuses and a prediction of 1991; Nixon & Boyle, 1982; Guerra & Nixon, 1987; Nixon et their future. al., 1988; Mather & Nixon, 1990; Nixon, 1987). Arnold & Arnold (1969) and Wodinsky (1969) both describe the act of drilling in detail. This behaviour consists INTRODUCTION of the following steps (Wodinsky, 1969): recognizing and selecting the prey, drilling a hole in the shell, ejecting a secre - Aristotle was the first to observe octopuses feed on mol - tory substance into the drilled hole, and removing the mollusc luscs (see D’Arcy Thompson, 1910), but it was Fujita who from its shell and eating it. -

Octopus Rubescens Berry, 1953 (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae), in the Mexican Tropical Pacific

17 4 NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 17 (4): 1107–1112 https://doi.org/10.15560/17.4.1107 Red Octopus, Octopus rubescens Berry, 1953 (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae), in the Mexican tropical Pacific María del Carmen Alejo-Plata1, Miguel A. Del Río-Portilla2, Oscar Illescas-Espinosa3, Omar Valencia-Méndez4 1 Instituto de Recursos, Universidad del Mar, Campus Puerto Ángel, Ciudad Universitaria, Puerto Ángel 70902, Oaxaca, México • plata@angel. umar.mx https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6086-0705 2 Departamento de Acuicultura, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE), B.C., Carretera Ensenada- Tijuana No. 3918, Zona Playitas, C.P. 22860, Ensenada, Baja California, México • [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5564- 6023 3 Posgrado en Ecología Marina, Universidad del Mar Campus Puerto Ángel, Oaxaca, México • [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000- 0003-1533-8453 4 Departamento El Hombre y su Ambiente, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Xochimilco, Calzada del Hueso 1100, 04960 Coyoacán, Cuida de México, México • [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8623-5446 * Corresponding author Abstract “Octopus” rubescens Berry, 1953 is an octopus of temperate waters of the western coast of North America. This paper presents the first record of “O.” rubescens from the tropical Mexican Pacific. Twelve octopuses were studied; 10 were collected in tide pools from five localities and two mature males were caught by fishermen in Oaxaca. We used mor- phometric characters and anatomical features of the digestive tract to identify the species. The five localities along the Mexican Pacific coast provide solid evidence that populations of this species have become established in tropical waters. -

The Biology, Ecology and Conservation of White's Seahorse

THE BIOLOGY, ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF WHITE’S SEAHORSE HIPPOCAMPUS WHITEI by DAVID HARASTI B.Sci. (Hons), University of Canberra – 1997 This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of the Environment, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. July 2014 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: ____________________________ ii ABSTRACT Seahorses are iconic charismatic species that are threatened in many countries around the world with several species listed on the IUCN Red List as vulnerable or endangered. Populations of seahorses have declined through over-exploitation for traditional medicines, the aquarium trade and for curios and through loss of essential habitats. To conserve seahorse populations in the wild, they are listed on Appendix II of CITES, which controls trade by ensuring exporting countries must be able to certify that export of seahorses is not causing a decline or damage to wild populations. Within Australia, seahorses are protected in several states and also in Commonwealth waters. The focus of this study was White’s seahorse Hippocampus whitei, a medium-sized seahorse that is found occurring along the New South Wales (NSW) coast in Australia. -

Western Central Pacific

FAOSPECIESIDENTIFICATIONGUIDEFOR FISHERYPURPOSES ISSN1020-6868 THELIVINGMARINERESOURCES OF THE WESTERNCENTRAL PACIFIC Volume2.Cephalopods,crustaceans,holothuriansandsharks FAO SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE FOR FISHERY PURPOSES THE LIVING MARINE RESOURCES OF THE WESTERN CENTRAL PACIFIC VOLUME 2 Cephalopods, crustaceans, holothurians and sharks edited by Kent E. Carpenter Department of Biological Sciences Old Dominion University Norfolk, Virginia, USA and Volker H. Niem Marine Resources Service Species Identification and Data Programme FAO Fisheries Department with the support of the South Pacific Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) and the Norwegian Agency for International Development (NORAD) FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1998 ii The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. M-40 ISBN 92-5-104051-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permissions, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, via delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. © FAO 1998 iii Carpenter, K.E.; Niem, V.H. (eds) FAO species identification guide for fishery purposes. The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific. Volume 2. Cephalopods, crustaceans, holothuri- ans and sharks. Rome, FAO. 1998. 687-1396 p. -

An Appraisal of the Effects of Clinical Anesthetics on Gastropod and Cephalopod Molluscs As a Step to Improved Welfare of Cephalopods

fphys-09-01147 August 23, 2018 Time: 9:4 # 1 REVIEW published: 24 August 2018 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01147 Sense and Insensibility – An Appraisal of the Effects of Clinical Anesthetics on Gastropod and Cephalopod Molluscs as a Step to Improved Welfare of Cephalopods William Winlow1,2,3*, Gianluca Polese1, Hadi-Fathi Moghadam4, Ibrahim A. Ahmed5 and Anna Di Cosmo1* 1 Department of Biology, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy, 2 Institute of Ageing and Chronic Diseases, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom, 3 NPC Newton, Preston, United Kingdom, 4 Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Physiology Research Centre, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran, 5 Faculty of Medicine, University of Garden City, Khartoum, Sudan Recent progress in animal welfare legislation stresses the need to treat cephalopod molluscs, such as Octopus vulgaris, humanely, to have regard for their wellbeing and to reduce their pain and suffering resulting from experimental procedures. Thus, Edited by: appropriate measures for their sedation and analgesia are being introduced. Clinical Pung P. Hwang, anesthetics are renowned for their ability to produce unconsciousness in vertebrate Academia Sinica, Taiwan species, but their exact mechanisms of action still elude investigators. In vertebrates Reviewed by: Robyn J. Crook, it can prove difficult to specify the differences of response of particular neuron types San Francisco State University, given the multiplicity of neurons in the CNS. However, gastropod molluscs such as United States Tibor Kiss, Aplysia, Lymnaea, or Helix, with their large uniquely identifiable nerve cells, make studies Institute of Ecology Research Center on the cellular, subcellular, network and behavioral actions of anesthetics much more (MTA), Hungary feasible, particularly as identified cells may also be studied in culture, isolated from *Correspondence: the rest of the nervous system. -

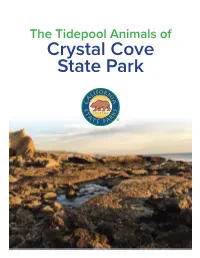

Crystal Cove State Park Tide Pool Data Collection Information Sheet

The Tidepool Animals of Crystal Cove State Park Tide Pool Data Collection Information Sheet Inverterbrate Groups Multiple Jointed Arms/Legs Echinoderms Allows animal to escape wave shock, avoid Body divided into five sections, tube feet, dehydration, salinity and temperature hard-spiny covering. extremes. Enables animals to escape predators and catch prey. Arthropods Jointed legs, segmented bodies, hard Camouflage Coloration exoskeleton. Enables animal to hide from and escape predators. Mollusks Soft body, enclosed by one shell, two shells Rapid Movement or possessing no shell. Usually has gills Allows animal to catch prey and escape and feet, with certain species possessing predators. multiple legs Sharp Spines Coelenterates Provides protection against predators and Stinging cells. Soft, saclike body for enables animal to burrow into rock as a ingesting food and eliminating waste. protection against wave shock. Body Part Regrowth Verterbrate Groups Enables animal to survive attacks by Fish predators and also wave shock. Gills for breathing, fins, and usually scales. Filter Feeding Ability to swim fast. Allows stationary animals to trap and eat Tidepool Adaptations plankton by filtering water through gills. Glue-like Threads Jointed Claws Produced by the body. Allow animal to stick Used for feeding and protection. to rocks and withstand wave shock. Ink-cloud Emission Tube Feet Used by animal to confuse and distract Allows animal to stick tightly to rocks, thus predators. protecting against wave shock. Also gives Eviceration animal movement into and out of water, The throwing up by an animal of its digestive which protects against dehydration. Feet system. This serves to distract and repulse are also able to pass food to the mouth in predators. -

Octopus Sinensis D'orbigny, 1841 (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae)

Species Diversity 21: 31–42 25 May 2016 DOI: 10.12782/sd.21.1.031 Octopus sinensis d’Orbigny, 1841 (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae): Valid Species Name for the Commercially Valuable East Asian Common Octopus Ian G. Gleadall International Fisheries Science Unit, Tohoku University Graduate School of Agricultural Science, 1-1 Amamiya, Sendai, Miyagi 981-8555, Japan E-mail: [email protected] (Received 21 July 2015; accepted 12 May 2016) http://zoobank.org/34118987-F3F3-4FEA-BD74-03218965CF84 The East Asian common octopus has long been synonymized with the Atlantic and Mediterranean species Octopus vulgaris Cuvier, 1797. However, evidence from molecular genetic studies has firmly established that the so-called cosmo- politan common octopus is in fact a group of several biogeographically distinct populations which form a complex of spe- cies with closely similar morphology. Here, a diagnosis and brief description are provided which distinguish the East Asian common octopus from O. vulgaris, and as a suitable name for it a former junior synonym of O. vulgaris is identified as a valid species: Octopus sinensis d’Orbigny, 1841. A neotype is designated. Voucher material includes specimens collected in Japan by Philipp Franz von Siebold and deposited in the National Museum of Natural History - Naturalis - in Leiden; and others that were studied by Madoka Sasaki in preparation for the detailed description of this species (as O. vulgaris) in a monograph on Japanese Cephalopoda published in 1929. At present, all species in this complex (particularly O. vulgaris and the East Asian species here identified as O. sinensis) are highly vulnerable to overfishing, so recognizing O.