Nez Perce Indians As Friends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Good Words: Chief Joseph and the Production of Indian Speech(Es), Texts, and Subjects

Good Words: Chief Joseph and the Production of Indian Speech(es), Texts, and Subjects Thomas H. Guthrie, Guilford College Abstract. Chief Joseph, who gained fame during the Nez Perce War of 1877, is one of the best-known Indian orators in American history. Yet the two principal texts attributed to him were produced under questionable circumstances, and it is unclear to what extent they represent anything he ever said. This essay examines the publication history of these texts and then addresses two questions about the treatment of Indian oratory in the nineteenth century. First, given their uncertain provenance, how and why did these texts become so popular and come to rep- resent Indian eloquence and an authentic Native American voice? Second, what was the political significance of Indian speech and texts of Indian oratory in the confrontation between Euro-Americans and Indians over land? I argue that the production and interpretation of Indian speech facilitated political subjugation by figuring Indians as particular kinds of subjects and positioning them in a broader narrative about the West. The discursive and political dimensions of the encounter were inseparable, as Indian “eloquence” laid the way for Indian defeat. I conclude by advocating a disruptive reading of Indian oratory that rejects the belief that a real Indian subject lies behind these texts in any straightforward sense. To make this argument, I draw on linguistic anthropology and critical theory, analyzing firsthand accounts, newspaper reports, and descriptions of Indian speech and Nez Perce history. In 1879 the North American Review published an article titled “An Indian’s View of Indian Affairs” that was attributed to Chief Joseph, or In-mut- too-yah-lat-lat (ca. -

Revised Area Profile

~a SITUATION Lewistown Resource Management Pl an Revision & Environmental Impact Statement Revised Area Profile FINAL Bureau of Land Management November 2019 Lewistown Field Office 920 Northeast Main Lewistown, MT 59457 i Visit our website at: https://go.usa.gov/xUPsP This page intentionally left blank. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Revised Analysis of Management Situation: Area Profile Page Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................................................5 2.RESOURCES……………………………………………………………………………………………………5 2.1 Air Resources and Climate………………………………………………………………………………………....6 2.2 Geology ..................................................................................................................................................... ..26 2.3 Soil Resources ............................................................................................................................................ 30 2.4 Water Resources ........................................................................................................................................ 35 2.5 Vegetation Communities .......................................................................................................................... 50 2.7 Wildland Fire Ecology and Management ............................................................................................. .83 2.8 Cultural and Heritage Resources ......................................................................................................... -

Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana

Report of Investigation 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg 2015 Cover photo by Richard Berg. Sapphires (very pale green and colorless) concentrated by panning. The small red grains are garnets, commonly found with sapphires in western Montana, and the black sand is mainly magnetite. Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology MBMG Report of Investigation 23 2015 i Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 Descriptions of Occurrences ..................................................................................................7 Selected Bibliography of Articles on Montana Sapphires ................................................... 75 General Montana ............................................................................................................75 Yogo ................................................................................................................................ 75 Southwestern Montana Alluvial Deposits........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Rock Creek sapphire district ........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Dry Cottonwood Creek deposit and the Butte area .................................... -

Through the Bitterroot Valley -1877

Th^ Flight of the NezFexce ...through the Bitterroot Valley -1877 United States Forest Bitterroot Department of Service National Agriculture Forest 1877 Flight of the Nez Perce ...through the Bitterroot Valley July 24 - Two companies of the 7th Infantry with Captain Rawn, sup ported by over 150 citizen volunteers, construct log barricade across Lolo Creek (Fort Fizzle). Many Bitterroot Valley women and children were sent to Fort Owen, MT, or the two hastily constructed forts near Corvallis and Skalkaho (Grantsdale). July 28 - Nez Perce by-pass Fort Fizzle, camp on McClain Ranch north of Carlton Creek. July 29 - Nez Perce camp near Silverthorn Creek, west of Stevensville, MT. July 30 - Nez Perce trade in Stevensville. August 1 - Nez Perce at Corvallis, MT. August 3 - Colonel Gibbon and 7th Infantry reach Fort Missoula. August 4 - Nez Perce camp near junction of East and West Forks of the Bitterroot River. Gibbon camp north of Pine Hollow, southwest of Stevensville. August 5 - Nez Perce camp above Ross' Hole (near Indian Trees Camp ground). Gibbon at Sleeping Child Creek. Catlin and volunteers agree to join him. August 6 - Nez Perce camp on Trail Creek. Gibbon makes "dry camp" south of Rye Creek on way up the hills leading to Ross' Hole. General Howard at Lolo Hot Springs. August 7 - Nez Perce camp along Big Hole River. Gibbon at foot of Conti nental Divide. Lieutenant Bradley sent ahead with volunteers to scout. Howard 22 miles east of Lolo Hot Springs. August 8 - Nez Perce in camp at Big Hole. Gibbon crosses crest of Continen tal Divide parks wagons and deploys his command, just a few miles from the Nez Perce camp. -

Yellowstone National Park to Canyon Creek, Montana

United States Department of Agriculture Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, to Broadview, Montana Experience the Nez Perce Trail Forest Service 1 Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, E NE C E R -M E P E to Canyon Creek, Montana - P 12 Z O E O N N L TM ATI RAI ONAL IC T The Nez Perce To Lavina H IST OR (Nee-Me-Poo) Broadview To Miles City 87 National Historic Trail 3 94 Designated by Congress in 1986, the entire Nez Perce National Historic Trail (NPNHT) stretches 1,170 miles 90 from the Wallowa Valley of eastern Oregon to the plains K E E Billings C R of north-central Montana. The NPNHT includes a N O To Crow Y Agency designated corridor encompassing 4,161 miles of roads, N A C trails and routes. 0 2.5 5 10 20 Miles Laurel This segment of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail from Yellowstone National Park to Broadview, Montana is 90 one of eight available tours (complete list on page 35). These N E R I V E Y E L L O W S T O R Columbus are available at Forest Service offices and other federal and 90 Rockvale local visitor centers along the route. Pryor As you travel this historic trail, you will see highway signs 212 E P d Nez Perce Route ryor R marking the official Auto Tour route. Each Mainstream US Army Route 310 Boyd Auto Tour route stays on all-weather roads passable for 90 Interstate 93 U.S. Highway all types of vehicles. -

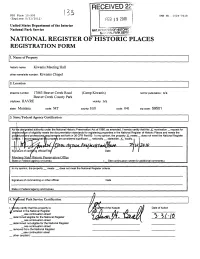

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) FEB 1 9 2010 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NAT. RreWTEFi OF HISTORIC '• NAPONALPARKSEFWI NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Kiwanis Meeting Hall other name/site number: Kiwanis Chapel 2. Location street & number: 17863 Beaver Creek Road (Camp Kiwanis) not for publication: n/a Beaver Creek County Park city/town: HAVRE vicinity: n/a state: Montana code: MT county: Hill code: 041 zip code: 59501 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As tr|e designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify t that this X nomination _ request for deti jrminalon of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Regist er of Historic Places and meets the pro i^duraland professional/equiremants set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ _ does not meet the National Register Crlt jfria. I JecommendJhat tnis propeay be considered significant _ nationally _ statewide X locally, i 20 W V» 1 ' Signature of certifj^ng official/Title/ Date / Montana State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency or bureau ( See continuation sheet for additional comments.) In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: Date of Action entered in the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined eligible for the National Register *>(.> 10 _ see continuation sheet _ determined not eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ removed from the National Register _see continuation sheet _ other (explain): _________________ Kiwanis Meeting Hall Hill County. -

Chief Joseph?

Frontier Grant Lesson Plan Teacher: Kim Uhlorn Topic: Native Americans of Idaho - History as a Mystery Case # 1840-1904 Subject & Grade: Social Studies 4th Duration of Lesson: 2 – 4 Class Periods Idaho Achievement Standards: 446.01: Acquire critical thinking and analytical skills. 446.01.d: Analyze, organize, and interpret information. 469.01.e: Analyze and explain human settlement as influenced by physical environment. 469.01.h: Describe the patterns and process of migration and diffusion. 469.04: Understand the migration and settlement of human populations on the earth’s surface 469.04.c: Describe ways in which human migration influences character of a place 473.01: Acquire critical thinking and analytical skills. 473.01.b: Differentiate between historical facts and historical interpretations. 474.01.e: Evaluate the impact of gender, race, ethnicity, religion, and national origin on individual/political rights 475.01: Understand the role of exploration and expansion in the development of the United States. Instructional Model Demonstrated: Inquiry Essential Question: What is the true story of Chief Joseph? Standards and Background Information: I want my students to understand (or be able to): A. Describe the history, interactions, and contributions Native Americans have made to Idaho. B.Understand the hardships and obstacles that Native Americans had to Overcome to be accepted and successful in early Idaho. II. Prerequisites: In order to fully appreciate this lesson, the students must know (or be experienced in): A. Understanding the concepts of immigration and migration. B. Understanding the various Native American groups that make up Idaho’s population. Lesson Objective(s): The students will: A. -

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report

United States Department of Agriculture Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report Summer 2019 Administrator ’s Corner At the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail (NPNHT) program, we work through partnerships that seek to create communication and collaboration across jurisdictional and cultural boundaries. Our ethic of working together reinforces community bonds, strengthens our Trail social fabric, and fosters community prosperity. By building stronger relationships and reaching out to underserved communities, who may have not historically had a voice in the management, interpretation of the Trail, we can more effectively steward our trail through honoring all the communities we serve. U.S. Forest Service photo, U.S. Roger Peterson Forest Service Volunteer labor isn’t perfect sometimes. Construction projects can take Sandra Broncheau-McFarland, speaking to longer than necessary, but there are so many intangible benefits of the Chief Joseph Trail Riders. volunteering- the friendships, the cross-cultural learning, and the life changes it inspires in volunteers who hopefully shift how they live, travel, and give in the future. Learning how to serve and teaching others the rest of our lives by how we live is the biggest impact. Volunteering is simply the act of giving your time for free and so much more. In an always on and interconnected world, one of the hardest things to find is a place to unwind. Our brains and our bodies would like us to take things a lot slower,” says Victoria Ward, author of “The Bucket List: Places to find Peace and Quiet.” This is the perfect time to stop and appreciate the amazing things happening around you. -

Chief Joseph & the Nez Perce

LESSON #7: CHIEF JOSEPH & THE NEZ PERCE (Grade 11/United States History) Written by Kris McIntosh Summary of Lesson: In this lesson, students will review and analyze the movement of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce tribe of the Northwest. The activity is intended to be used in the context of other Social Studies lessons and activities to provide students with a comprehensive study of U.S. Government Indian policy in the late 19th century. Objective: Students will o Analyze paintings, photos, maps, and census reports detailing the flight of the Nez Perce in 1877, and o Produce a narrative newspaper article based on their analysis. TEKS: (US 10A) Geography. The student understands the effects of migration and immigration on American society, and is expected to analyze the effects of changing demographic patterns resulting from migration within the United States. (US 2A) History. The student understands the political, economic, and social changes in the United States from 1877 to 1898. The student is expected to analyze political issues such as Indian policies. Time Required: Two class periods Materials: Copies (or a projector to share items with entire class) of: Sid Richardson Museum painting The Snow Trail by Charles M. Russell Photographs of Chief Joseph NARA Photo Analysis Sheet Chief Joseph history Bureau of Indian Affairs maps Census data for Chief Joseph Magnifying glasses Procedure: After students have studied the movement to put and keep Native Americans on reservations, and the Battle of Little Big Horn, introduce the lesson. o Show students The Snow Trail, a painting by Charles M. Russell. -

Idaho County School Survey Report PSLLC

CULTURAL RESOURCE SURVEY HISTORIC RURAL SCHOOLS OF IDAHO COUNTY Prepared for IDAHO COUNTY HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION GRANGEVILLE, IDAHO By PRESERVATION SOLUTIONS LLC September 1, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 2 Preface: What is a Cultural Resource Survey? ........................................................................... 3 Methodology Survey Objectives ........................................................................................................... 4 Scope of Work ................................................................................................................. 7 Survey Findings Dates of Construction .................................................................................................... 12 Functional Property Types ............................................................................................. 13 Building Forms .............................................................................................................. 13 Architectural Styles ........................................................................................................ 19 Historic Contexts Idaho County: A Development Overview: 1860s to 1950s ............................................. 24 Education in Idaho County: 1860s to -

Final Environmental Impact Statement Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Final Environmental Impact Statements (ID) Idaho 1997 Final Environmental Impact Statement Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield United States, Department of the Interior, National Park Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/idaho_finalimpact Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation United States, Department of the Interior, National Park Service, "Final Environmental Impact Statement Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield" (1997). Final Environmental Impact Statements (ID). Paper 22. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/idaho_finalimpact/22 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Idaho at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Final Environmental Impact Statements (ID) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIt>51-S-0S FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT NEZ PERCE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK AND BIG HOLE NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD JULY 1997 AsorIN AND OKANOGAN C OUNTlES, W ASHINGTON W ALLOWA C Ol1l'olY, OREGON NEZ PERCE, IDAHO, L EWIS, CLEARWATER, AND ClARK C OUNTTES, IDAHO BWNE, YELLOWSTONE, AND BEAVERHEAD COUNTIES, M OM'AN'" INTRODUCTION This Fitla / Enuironmental lmpact Statement for Nez P~ rc e National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield is an abbreviated document. It is important to understand that this Final Environmental Impact Statement must be read in conjunction with the previously published. Draf t General Management Plan/Enuironmental lmpact Statement. A notice of availability of the Draft General Management PlanlEnuironmental Impact Statement was published in the Federal Register, Vol. 61, No. 199, p. -

Indian Tribal Rights and the National Forests: the Case of the Aboriginal Lands of the Nez Perce Tribe

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 1998 Indian Tribal Rights and the National Forests: The Case of the Aboriginal Lands of the Nez Perce Tribe Charles F. Wilkinson University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Legal History Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Citation Information Charles F. Wilkinson, Indian Tribal Rights and the National Forests: The Case of the Aboriginal Lands of the Nez Perce Tribe, 34 IDAHO L. REV. 435 (1998), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/ 650. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 34 Idaho L. Rev. 435 1997-1998 Provided by: William A. Wise Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Mon Jun 5 17:33:02 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text.