Revised Area Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana

Report of Investigation 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg 2015 Cover photo by Richard Berg. Sapphires (very pale green and colorless) concentrated by panning. The small red grains are garnets, commonly found with sapphires in western Montana, and the black sand is mainly magnetite. Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology MBMG Report of Investigation 23 2015 i Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 Descriptions of Occurrences ..................................................................................................7 Selected Bibliography of Articles on Montana Sapphires ................................................... 75 General Montana ............................................................................................................75 Yogo ................................................................................................................................ 75 Southwestern Montana Alluvial Deposits........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Rock Creek sapphire district ........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Dry Cottonwood Creek deposit and the Butte area .................................... -

Yellowstone National Park to Canyon Creek, Montana

United States Department of Agriculture Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, to Broadview, Montana Experience the Nez Perce Trail Forest Service 1 Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, E NE C E R -M E P E to Canyon Creek, Montana - P 12 Z O E O N N L TM ATI RAI ONAL IC T The Nez Perce To Lavina H IST OR (Nee-Me-Poo) Broadview To Miles City 87 National Historic Trail 3 94 Designated by Congress in 1986, the entire Nez Perce National Historic Trail (NPNHT) stretches 1,170 miles 90 from the Wallowa Valley of eastern Oregon to the plains K E E Billings C R of north-central Montana. The NPNHT includes a N O To Crow Y Agency designated corridor encompassing 4,161 miles of roads, N A C trails and routes. 0 2.5 5 10 20 Miles Laurel This segment of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail from Yellowstone National Park to Broadview, Montana is 90 one of eight available tours (complete list on page 35). These N E R I V E Y E L L O W S T O R Columbus are available at Forest Service offices and other federal and 90 Rockvale local visitor centers along the route. Pryor As you travel this historic trail, you will see highway signs 212 E P d Nez Perce Route ryor R marking the official Auto Tour route. Each Mainstream US Army Route 310 Boyd Auto Tour route stays on all-weather roads passable for 90 Interstate 93 U.S. Highway all types of vehicles. -

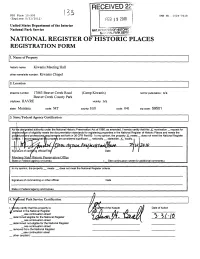

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) FEB 1 9 2010 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NAT. RreWTEFi OF HISTORIC '• NAPONALPARKSEFWI NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Kiwanis Meeting Hall other name/site number: Kiwanis Chapel 2. Location street & number: 17863 Beaver Creek Road (Camp Kiwanis) not for publication: n/a Beaver Creek County Park city/town: HAVRE vicinity: n/a state: Montana code: MT county: Hill code: 041 zip code: 59501 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As tr|e designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify t that this X nomination _ request for deti jrminalon of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Regist er of Historic Places and meets the pro i^duraland professional/equiremants set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ _ does not meet the National Register Crlt jfria. I JecommendJhat tnis propeay be considered significant _ nationally _ statewide X locally, i 20 W V» 1 ' Signature of certifj^ng official/Title/ Date / Montana State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency or bureau ( See continuation sheet for additional comments.) In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: Date of Action entered in the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined eligible for the National Register *>(.> 10 _ see continuation sheet _ determined not eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ removed from the National Register _see continuation sheet _ other (explain): _________________ Kiwanis Meeting Hall Hill County. -

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report

United States Department of Agriculture Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report Summer 2019 Administrator ’s Corner At the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail (NPNHT) program, we work through partnerships that seek to create communication and collaboration across jurisdictional and cultural boundaries. Our ethic of working together reinforces community bonds, strengthens our Trail social fabric, and fosters community prosperity. By building stronger relationships and reaching out to underserved communities, who may have not historically had a voice in the management, interpretation of the Trail, we can more effectively steward our trail through honoring all the communities we serve. U.S. Forest Service photo, U.S. Roger Peterson Forest Service Volunteer labor isn’t perfect sometimes. Construction projects can take Sandra Broncheau-McFarland, speaking to longer than necessary, but there are so many intangible benefits of the Chief Joseph Trail Riders. volunteering- the friendships, the cross-cultural learning, and the life changes it inspires in volunteers who hopefully shift how they live, travel, and give in the future. Learning how to serve and teaching others the rest of our lives by how we live is the biggest impact. Volunteering is simply the act of giving your time for free and so much more. In an always on and interconnected world, one of the hardest things to find is a place to unwind. Our brains and our bodies would like us to take things a lot slower,” says Victoria Ward, author of “The Bucket List: Places to find Peace and Quiet.” This is the perfect time to stop and appreciate the amazing things happening around you. -

The Archean Geology of Montana

THE ARCHEAN GEOLOGY OF MONTANA David W. Mogk,1 Paul A. Mueller,2 and Darrell J. Henry3 1Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana 2Department of Geological Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 3Department of Geology and Geophysics, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana ABSTRACT in a subduction tectonic setting. Jackson (2005) char- acterized cratons as areas of thick, stable continental The Archean rocks in the northern Wyoming crust that have experienced little deformation over Province of Montana provide fundamental evidence long (Ga) periods of time. In the Wyoming Province, related to the evolution of the early Earth. This exten- the process of cratonization included the establishment sive record provides insight into some of the major, of a thick tectosphere (subcontinental mantle litho- unanswered questions of Earth history and Earth-sys- sphere). The thick, stable crust–lithosphere system tem processes: Crustal genesis—when and how did permitted deposition of mature, passive-margin-type the continental crust separate from the mantle? Crustal sediments immediately prior to and during a period of evolution—to what extent are Earth materials cycled tectonic quiescence from 3.1 to 2.9 Ga. These compo- from mantle to crust and back again? Continental sitionally mature sediments, together with subordinate growth—how do continents grow, vertically through mafi c rocks that could have been basaltic fl ows, char- magmatic accretion of plutons and volcanic rocks, acterize this period. A second major magmatic event laterally through tectonic accretion of crustal blocks generated the Beartooth–Bighorn magmatic zone assembled at continental margins, or both? Structural at ~2.9–2.8 Ga. -

2017 Wings Reg. Brochure

program 17 layout:Layout 1 2/22/17 2:10 PM Page 1 18th ANNUAL MONTANA AUDUBON BIRD FESTIVAL June 9–11, 2017 Best Western Plus Heritage Inn Great Falls, Montana John Lambing Russell Hill program 17 layout:Layout 1 2/22/17 2:10 PM Page 2 welcome Festival headquarters and lodging The Best Western Plus Heritage Inn is located off the 10th Avenue South We will be celebrating the milestone of Montana (I-15) exit in Great Falls and is within minutes of the CM Russell Museum, Audubon’s first 40 Years at our 18th Annual Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center, Giant Springs State Park, First People’s Wings Across the Big Sky Festival, co-hosted by Buffalo Jump, Great Falls International Airport, Holiday Village Mall, and the the Upper Missouri Breaks Audubon Chapter. Rivers Edge Trail along the Missouri River. As the largest full-service hotel in This is shaping up to be a spectacular event and Central Montana with 231 guest rooms and over 17,000 sq. ft. event space we hope you will join us in Great Falls, June 9–11, with 12 meeting rooms, we are able to accommodate groups of all sizes. 2017. Registration will open at 1:00 p.m. so plan Complimentary features include: airport and area-wide transportation, to sign in and enjoy a special presentation parking, wireless internet, indoor pool and fitness center. The address is Friday afternoon, followed by a Barbecue and 1700 Fox Farm Road and is easily accessible from the south, north or west Celebration Friday evening. -

National Historic Trail

at the Big Hole on August 9. August on Hole Big the at attack on their sleeping village sleeping their on attack crossing of the Missouri River, Montana River, Missouri the of crossing repelled a devastating army army devastating a repelled Steamboat Rock near Cow Island Island Cow near Rock Steamboat battles and skirmishes, and and skirmishes, and battles US Forest Service Image Service Forest US masterfully in some 20 20 some in masterfully 2,000 horses, they fought fought they horses, 2,000 and sick. Leading a herd of of herd a Leading sick. and were women, children, old old children, women, were 250 were warriors: the rest rest the warriors: were 250 fled for their lives. Only Only lives. their for fled 750 Nez Perce desperately desperately Perce Nez 750 they did not seek, nearly nearly seek, not did they Swept into a fight fight a into Swept involvement in it whatsoever. it in involvement Looking Glass band into conflict; the village had sought to avoid any any avoid to sought had village the conflict; into band Glass Looking Canyon. Two weeks later, an unprovoked army attack brought the the brought attack army unprovoked an later, weeks Two Canyon. June 17 after they defeated a cavalry force at the Battle of White Bird Bird White of Battle the at force cavalry a defeated they after 17 June The Nez Perce flight began June 15, 1877 and intensified on on intensified and 1877 15, June began flight Perce Nez The murders of relatives by killing some white settlers. white some killing by relatives of murders vengeance. -

Nez Perce National Historic Trail

Nez Perce National Historic Trail OREGON IDAHO MONTANA • WYOMING Nez Perce campsite, Big Hole National Battlefield, Montana STATE OF MONTANA FOREST NATIONAL BUREAU OF DEPARTMENT OF SERVICE PARK SERVICE LAND MANAGEMENT FISH, WILDLIFE & PARKS ongress passed the National Trails System Act in 1968 establishing a frame C work for a nationwide system of scenic, recreational, and historic trails. The Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) Trail, extending approximately 1,170 miles from the vicinity of Wallowa Lake, Oregon, to the Bears Paw Battlefield near Chinook, Montana, was added to this System by Congress as a National Historic Trail in 1986. The Nez Perce Indians, composed origi nally of a number of independent villages and Mountainous terrain along the trail, bands, were long known as friends of the whites. Crandall Creek, Wyoming They had welcomed Lewis and Clark, fur trappers, and missionaries to their homeland in the moun tains, valleys, and along the rivers of southeastern Washington, northeastern Oregon, and northcen- tral Idaho. In 1855, Washington Territorial Governor, Isaac I. Stevens, responding to increas ing white expansion, negotiated a treaty with the Nez Perce chiefs, recognizing their peoples' right to their traditional homeland and establishing it as a reservation of some 5,000 square miles. In 1860, prospectors, encroaching on Nez Perce lands, struck gold. In the ensuing rush, thousands of miners, merchants, and settlers, disregarding Stevens's treaty, overran large parts Steamboat Rock near Cow Island of the reservation, appropriating the Indians' lands crossing of the Missouri River, Montana and livestock and heaping mistreatment and injustices on the Nez Perces. To cope with the crisis, the United States Government engaged the There is irony in the tragic fate of the angered Nez Perce in new treaty talks that culmi Nez Perces. -

Central Montana

CENTRAL MONTANA 46 CENTRAL MONTANA - VISITMT.COM CENTRAL MONTANA CENTRAL MONTANA www.centralmontana.com · 800.527.5348 When it comes to Central Montana, the question is, how far back in time would you like to go? To 1960s kitsch at the Sip‘n Dip in Great Falls, a tiki bar with live performing mermaids? To Rockwellian winters, schussing the time- honored slopes of Montana’s oldest ski area? Or back to painter Charlie Russell’s frontier West, viewed from the windows of a dinner train? Here, you’ll experience Fort Benton’s days as a fur-trading outpost; Lewis and Clark’s 1805–06 Montana expedition; and Bear Paw Battlefield, where Chief Joseph resigned to “fight no more forever.” This land of sunny wheat fields, snowy plains and rolling mountains can take you back to a time before human civilization, too, like Choteau’s Cretaceous days as a hip dinosaur hangout. Or go back farther still, to geologic time, when sandstone rock formations slowly emerged along the Upper Missouri National Wild and Scenic River, and the entire Rocky Mountain Front lifted into existence. While Central Montana is home to 21st-century trappings like one of Montana’s largest wind farms, even everyday interactions here are tinged with a sort of old-fashioned charm. Chatting with the guy at the next ice fishing hole, swapping field notes with fellow birders and running into skinny-skiers on the trails, you’ll find folks warmly welcoming and unpretentious, much like the hotels, cafes, saloons and museums. In such a laid-back, unbustling place, it’s easy to feel like you have all the time in the world...maybe because you do. -

Where Did the Nez Perces Go in Yellowstone in 1877?

Portland State University PDXScholar History Faculty Publications and Presentations History 1-1-1990 Where did the Nez Perces go in Yellowstone in 1877? William L. Lang Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/hist_fac Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Lang, W. L. (1990). Where did the Nez Perces go in Yellowstone in 1877?. Montana: The Magazine Of Western History, 40(1), 14-29. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Where Did the Nez Perces by William L. Lang On October 5, 1877, at the end of one of the trulyheroic episodes in the Indian Wars in the Northwest, Chief Joseph of the Nez Percessurrendered to General Nelson A. Miles on a snow-dustedbattlefield along Snake Creek near present- day Havre, Montana. The Indians gave up just forty-some miles short of their destination-the international border with Canada,where they hoped to find a sanctuary.They had been pursued for nearly three months and over thirteen hundredmiles fromtheir reservationin central Idaho,testing the military'sskill and their own stamina. In his surrender message,Joseph describedhis people's condition as destitute and his warriorsas tired of the struggle."I will fight no more forever"-purportedly Joseph's words-became an anthem and was symbolic of the Nez Perces' struggleand failure to . -

4—Affected Environment 171

4 — Affected Environment This chapter describes the characteristics and re- dismissed from further consideration because there sources of the refuge and how existing or past man- would be no effects, or effects would be negligible or agement or influences have affected these resources. not detectable, as discussed below. It specifically addresses the physical environment, biological environment, special land designations, MOOSE recreational opportunities, cultural and paleontolog- Moose have occasionally been observed on the ref- ical resources including a history of human use on uge, often young dispersing bulls from central Mon- the site, and the socioeconomic environment. Ser- tana mountain ranges or southern Canada. Although vice data and other information, both published and there are substantial willow communities in the Mis- unpublished, was used to quantify what is known souri River floodplain, the area is generally not con- about refuge resources. Additionally, other sources sidered suitable moose habitat. Nonetheless, in were used including data and information from other recent years moose appear to be expanding their agencies or other scientific studies. range in parts of eastern Montana and in many places in the North Dakota prairies, and could potentially extend their range onto the refuge, but currently 4.1 TOPICS not ANALYZED they are not a common species on the refuge. FURTHER BLACK BEAR The affected environment describes those parts of A few black bear sightings have been reported on the natural and human environment that could be the refuge over the years, but none have become affected by implementing any of the management established residents and the Missouri River Breaks alternatives. -

Northwest Education, 2002-2003. INSTITUTION Northwest Regional Educational Lab., Portland, OR

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 478 246 RC 024 128 AUTHOR Sherman, Lee, Ed.; Boss, Suzie, Ed.; Weeks, Denise Jarrett, Ed TITLE Northwest Education, 2002-2003. INSTITUTION Northwest Regional Educational Lab., Portland, OR. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 198p.; Published quarterly. Photographs and a few colored pages may not reproduce adequately. For volume 7, see ED 464 798. For individual articles, see RC 515 704-711, RC 515 825- 831, RC 515 966-968, and RC 516 117-123. CONTRACT ED -01 -CO -0013 AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.nwrel.org/nwedu. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Northwest Education; v8 n1-4 Fall-Sum 2002-2003 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Achievement Gains; *Educational Practices; Elementary Secondary Education; *Gifted Disabled; *History Instruction; Learning Disabilities; Minority Groups; United States History; *Writing Instruction IDENTIFIERS *Lewis and Clark Expedition; *United States (Northwest) ABSTRACT This document contains the four issues of Northwest Education published during the 2002-03 school year. Issue themes are: (1) "Closing the Gap: How Northwest Schools Are Raising Minority Achievement"; (2) "Focus on Writing"; (3) "The Hidden Disability: When Bright Children Struggle To Learn"; and (4)"Discoveries in Learning: Lessons from Lewis & Clark." Typically, each issue consists of a lead article that reviews current research or provides an overview of matters related to the theme, followed by articles describing model programs and practices or profiling relevant experiences in schools of the Northwest Washington,. Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Alaska. Issues also contain information on related resources, book reviews, letters from readers, and practitioner commentary.(SV) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document.