Sanbõkyõdan Zen and the Way of the New Religions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Still Mind at 20 Years: a Personal Reflection GATE

March 2014 Vol.10 No. 1 in a one-room zendo in Jersey City. So I invited folks from a series of meditation sessions that Roshi had led at a church in Manhattan, as well as people I was seeing in my spiritual direction work who were interested in meditation. We called ourselves Greenwich Village Zen Community (GVZC) and Sensei Kennedy became our first teacher. We sat on chairs or, in some cases, on toss pillows that were strewn on the comfortable library sofa; there was no altar, no daisan, only two periods of sitting with kin-hin in between, along with some basic instruction. My major . enduring memory is that on most Tuesdays as we began Still sitting at 7 pm, the chapel organist would begin his weekly practice. The organ was on the other side of the library wall so our sitting space was usually filled with Bach & Co. Having come to Zen to “be in silence,” it drove me rather crazy. Still Mind at 20 Years: I didn’t have to worry too much, though, because after a few months the staff told us the library was no longer available. So we moved, literally down the street, to the A Personal Reflection (cont. on pg 2) by Sensei Janet Jiryu Abels Still Mind Zendo was founded on a selfish act. I needed a sangha to support my solo practice and, since none existed, I formed one. Now, 20 years later, how grateful I am that enough people wanted to come practice with each other back then, for this same sangha has proved to be the very rock of my continuing awakening. -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

PUBLICATION of SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS

PUBLICATION OF SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS TALKS 3 The Gift of Zazen BY Shunryu Suzuki-roshi 16 Practice On and Off the Cushion BY Anna Thom 20 The World Is Vast and Wide BY Gretel Ehrlich 36 An Appropriate Response BY Abbess Linda Ruth Cutts POETRY AND ART 4 Kannon in Waves BY Dan Welch (See also front cover and pages 9 and 46) 5 Like Water BY Sojun Mel Weitsman 24 Study Hall BY Zenshin Philip Whalen NEWS AND FEATURES 8 orman Fischer Revisited AN INTERVIEW 11 An Interview with Annie Somerville, Executive Chef of Greens 25 Projections on an Empty Screen BY Michael Wenger 27 Sangha-e! 28 Through a Glass, Darkly BY Alan Senauke 42 'Treasurer's Report on Fiscal Year 2002 DY Kokai Roberts 2 covet WNO eru 111 -ASSl\ll\tll.,,. o..N WEICH The Gi~ of Zazen Shunryu Suzuki Roshi December 14, 1967-Los Altos, California JAM STILL STUDYING to find out what our way is. Recently I reached the conclusion that there is no Buddhism or Zen or anythjng. When I was preparing for the evening lecture in San Francisco yesterday, I tried to find something to talk about, but I couldn't; then I thought of the story 1 was told in Obun Festival when I was young. The story is about water and the people in Hell Although they have water, the people in hell cannot drink it because the water burns like fire or it looks like blood, so they cannot drink it. -

The Ven. Eido Tai Shimano Roshi, Founder of Two American Rinzai Zen

The Ven. Eido Tai Shimano Roshi, founder of two American Rinzai Zen temples, died February 18 shortly after presenting teachings at Shogen-ji Junior College in Gifu, Japan. He was 85. He moved to Hawaii in 1960 after many years of intensive practice at Ryutaku-ji in Mishima, Japan with the late Soen Nakagawa Roshi. He settled in New York City in 1965, and was asked to become president of the Zen Studies Society, which had been established in 1956 to assist the Buddhist scholar D.T. Suzuki in his pioneering efforts to introduce Zen to the West. He established New York Zendo Shobo-Ji, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, on Sept. 15, 1968, and International Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-Ji, in the Catskill Mountains of Upstate New York, on July 4, 1976. Eido Roshi received Dharma Transmission from Soen Nakagawa Roshi on Sept. 15, 1972, and served as the abbot of New York Zendo and Dai Bosatsu Zendo until his retirement in 2010. He was the author of Points of Departure; Golden Wind; and Zen Word, Zen Calligraphy. He brought out a translation of The Book of Rinzai: the Recorded Sayings of Master Rinzai, and translated several volumes of Eihei Dogen’s Shobogenzo. He gave teachings and held retreats throughout the world, and was the recipient of the Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai award, honoring his remarkable achievements and contributions in bringing the teachings of Buddhism to the West. In the Postscript to his section of the book Namu Dai Bosa: A Transmission of Zen Buddhism to America, edited by Louis Nordstrom, Eido Roshi wrote: “On the Way to Dai Bosatsu I met many travelers. -

Fall 1969 Wind Bell

PUBLICATION OF ZEN •CENTER Volume Vilt Nos. 1-2 Fall 1969 This fellow was a son of Nobusuke Goemon Ichenose of Takahama, the province of Wakasa. His nature was stupid and tough. When he was young, none of his relatives liked him. When he was twelve years old, he was or<Llined as a monk by Ekkei, Abbot of Myo-shin Monastery. Afterwards, he studied literature under Shungai of Kennin Monastery for three years, and gained nothing. Then he went to Mii-dera and studied Tendai philosophy under Tai-ho for. a summer, and gained nothing. After this, he went to Bizen and studied Zen under the old teacher Gisan for one year, and attained nothing. He then went to the East, to Kamakura, and studied under the Zen master Ko-sen in the Engaku Monastery for six years, and added nothing to the aforesaid nothingness. He was in charge of a little temple, Butsu-nichi, one of the temples in Engaku Cathedral, for one year and from there he went to Tokyo to attend Kei-o College for one year and a half, making himself the worst student there; and forgot the nothingness that he had gained. Then he created for himself new delusions, and came to Ceylon in the spring of 1887; and now, under the Ceylon monk, he is studying the Pali Language and Hinayana Buddhism. Such a wandering mendicant! He ought to <repay the twenty years of debts to those who fed him in the name of Buddhism. July 1888, Ceylon. Soyen Shaku c.--....- Ocean Wind Zendo THE KOSEN ANO HARADA LINEAOES IN AMF.RICAN 7.llN A surname in CAI':> andl(:attt a Uhatma heir• .l.incagea not aignilleant to Zen in Amttka arc not gi•cn. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

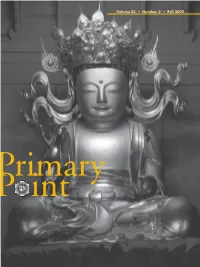

Volume 23 • Number 2 • Fall 2005

Volume 23 • Number 2 • Fall 2005 Primary Point Primary Point 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Telephone 401/658-1476 • Fax 401/658-1188 www.kwanumzen.org • [email protected] online archives www.kwanumzen.org/primarypoint Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonprofit religious corporation. The founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the first Korean Zen Master to live and teach in the West. In 1972, after teaching in Korea and Japan for many years, he founded the Kwan Um sangha, which today has affiliated groups around the world. He gave transmission to Zen Masters, and “inka”—teaching authority—to senior students called Ji Do Poep Sa Nims, “dharma masters.” The Kwan Um School of Zen supports the worldwide teaching schedule of the Zen Masters and Ji Do Poep Sa Nims, assists the member Zen centers and groups in their growth, issues publications In this issue on contemporary Zen practice, and supports dialogue among religions. If you would like to become a member of the School and receive Let’s Spread the Dharma Together Primary Point, see page 29. The circulation is 5000 copies. Seong Dam Sunim ............................................................3 The views expressed in Primary Point are not necessarily those of this journal or the Kwan Um School of Zen. Transmission Ceremony for Zen Master Bon Yo ..............5 © 2005 Kwan Um School of Zen Founding Teacher In Memory of Zen Master Seung Sahn Zen Master Seung Sahn No Birthday, No Deathday. Beep. Beep. School Zen Master Zen -

Relationships Zen Bow : Relationships

non‑profit a publication of organization u.s. postage the rochester zen center paid permit no. 1925 � rochester, ny volume xxxvi · number 4· 2013‑14 rochester zen center 7 arnold park rochester, ny 14607 Address service requested Zen Bow subscribing to number 1 · 2014 Zen Bow Upholding the Precepts The subscription rate is as follows : The Ten Cardinal Precepts offer us a guide Four issues Eight issues U.S. : $20.00 $40.00 to living in harmony with others and with Foreign : $30.00 $60.00 compassion toward all sentient beings. To‑ gether, they articulate the conduct and char‑ Please send checks and your current address acter we can realize through Zen practice. to : Although the precepts are subject to different Zen Bow Subscriptions Desk interpretations, upholding them helps us to Rochester Zen Center continually acknowledge our transgressions, 7 Arnold Park seek reconciliation, and renew our commit‑ Rochester, NY 14607 ment to the Dharma. Please Note : If you are moving, the Postal Ser‑ Readers are invited to submit articles and im‑ vice charges us for each piece of mail sent to ages to the editors, Donna Kowal and Brenda your old address, whether you have left a for‑ Reeb, at [email protected]. warding address or not. So if you change your Submission deadline: June 27, 2014 address, please let us know as soon as possi‑ ble. Send your address corrections to the Zen Bow Subscriptions Desk at the above address or email [email protected]. relationships Zen Bow : Relationships volume xxxvi · number 4 · 2013-14 Zen Practice as Relationship -

The Zen Koan; Its History and Use in Rinzai

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE TRENT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/zenkoanitshistorOOOOmiur THE ZEN KOAN THE ZEN KOAN ITS HISTORY AND USE IN RINZAI ZEN ISSHU MIURA RUTH FULLER SASAKI With Reproductions of Ten Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku A HELEN AND KURT WOLFF BOOK HARCOURT, BRACE & WORLD, INC., NEW YORK V ArS) ' Copyright © 1965 by Ruth Fuller Sasaki All rights reserved First edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-19104 Printed in Japan CONTENTS f Foreword . PART ONE The History of the Koan in Rinzai (Un-chi) Zen by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Koan in Chinese Zen. 3 II. The Koan in Japanese Zen. 17 PART TWO Koan Study in Rinzai Zen by Isshu Miura Roshi, translated from the Japanese by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Four Vows. 35 II. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (i) . 37 vii 8S988 III. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (2) . 41 IV. The Hosshin and Kikan Koans. 46 V. The Gonsen Koans . 52 VI. The Nanto Koans. 57 VII. The Goi Koans. 62 VIII. The Commandments. 73 PART THREE Selections from A Zen Phrase Anthology translated by Ruth F. Sasaki. 79 Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku.123 Index.147 viii FOREWORD The First Zen Institute of America, founded in New York City in 1930 by the late Sasaki Sokei-an Roshi for the purpose of instructing American students of Zen in the traditional manner, celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary on February 15, 1955. To commemorate that event it invited Miura Isshu Roshi of the Koon-ji, a monastery belonging to the Nanzen-ji branch of Rinzai Zen and situated not far from Tokyo, to come to New York and give a series of talks at the Institute on the subject of koan study, the study which is basic for monks and laymen in traditional, transmitted Rinzai Zen. -

The Zen Studies Society

T H E N E W S L E T T E R O F THE ZEN STUDIES SOCIETY View of Mt. Fuji from Mt. Dai Bosatsu W I N T E R / S P R I N G 2006 Teisho on Rinzai Roku, The Book of Rinzai, Chapter 14 Eido T. Shimano Roshi 2 Dharma talk on Mumonkan, Gateless Gate Case 19 Roko ni-Osho Sherry Chayat 8 Dogyo-ninin (We Two Together) Shoshin Anne Hughes 13 Diary of Our Pilgrimage 2005 Seigan Ed Glassing 18 Dream? Fujin Zenni 25 My Impressions of the Pilgrimage to Japan Doshin David Schubert 26 Yamakawa Roshi performing Dai-Hannya View from inside the Genkan of Shogen-ji Our Trip October 2005 Yayoi Karen Matsumoto 27 Sesshin at Shogen-ji Saiun Atsumi Hara 29 Mandala Memories Banko Randy Phillips 31 Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji News 33 New York Zendo Shobo-ji News 36 Zen Studies Society News 37 Dai Bosatsu Zendo 2006 Calendar 39 New York Zendo 2006 Calendar 40 Published twice annually by The Zen Studies Society, Inc. Eido T. Shimano Roshi, Abbot Offices: New York Zendo Shobo-ji 223 East 67th Street New York, NY 10021-6087 Tel (212)861-3333 Fax 628-6968 offi[email protected] Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji 223 Beecher Lake Road Livingston Manor, NY 12758-6000 Tel (845)439-4566 Fax 439-3119 Roshi stands on top of Mount Dai Bosatsu offi[email protected] Editor: Seigan Edwin Glassing; News: Aiho-san Y. Shimano, Seigan Edwin Glassing, Fujin Zenni, Jokei Megumi Kairis; Graphic design:Banko Randy Phillips; Editorial Assistant and Proofreading: Myochi Nancy O’Hara; Teisho Transcription and Editing: Jimin Anna Klegon; Final Editing: Myochi Nancy O’Hara Photo Credits: Junsho Shelley Bello (pp. -

Primary Point, Vol 5 Num 3

I 'I Non Profit Org. �I 'I U.S. Postage /I J PAID 1 Address Correction Requested i Permit #278 ,:i Return Postage Guaranteed Providence, RI 'I Ii ARY OINT PUBLISHED BY THE KWAN UM ZENSCHOOL K.B.C. Hong Poep Won VOLUME FIVE, NUMBER THREE 528 POUND ROAD, CUMBERLAND, RI 02864 (401)658-1476 NOVEMBER 1988 PERCEIVE UNIVERSAL SOUND An Interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn. we are centered we can control our This interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn strongly and thus our condition and situation. appeared in "The American Theosophist" feelings, (AT) in May 1985. It is reprinted by permis AT: When you refer to a "center" do you sion of the Theosophical Society in America, mean any particular point in the body? Wheaton, Illinois. The interviewer is Gary DSSN: No, it is not just one point. To be Doore. Zen Master Sahn is now ,I Seung strongly centered is to be at one with the to his students as Dae Soen Sa referred by universal center, which means infinite time Nim. (See note on 3) page and infinite space. Doore: What is Zen Gary chanting? The first time one tries chanting medita Seung Sahn (Dae Soen Sa Nim): Chanting is tion there will be much confused thinking, very important in our practice. We call it many likes, dislikes and so on. This indicates "chanting meditation." Meditation means keep that the whole mind is outwardly-oriented. ing a not-moving mind. The important thing in Therefore, it is necessary first to return to chanting meditation is to perceive the sound of one's energy source, to return to a single point. -

Review Of" Unsui: a Diary of Zen Monastic Life" by E. Nishimura

Swarthmore College Works Religion Faculty Works Religion 10-1-1975 Review Of "Unsui: A Diary Of Zen Monastic Life" By E. Nishimura Donald K. Swearer Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-religion Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Donald K. Swearer. (1975). "Review Of "Unsui: A Diary Of Zen Monastic Life" By E. Nishimura". Philosophy East And West. Volume 25, Issue 4. 495-496. DOI: 10.2307/1398231 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-religion/122 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 495 is, to write a twentieth century Cloud of' Unknowing (a Christian document) by using Buddhism. PAUL WIENPAHL University of California, Santa Barbara Unsui: A Diary of Zen Monastic Life, by Eshin Nishimura, edited by Bardwell L. Smith, drawings by Giei Sa to . Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1973 . In Unsui Eshin Nishimura and Bardwell Smith have put together a thoroughly delightful volume on Zen Buddhist training and monastic life. The book combines ninety-six comic, cartoonlike color drawings by Giei Sato (1920- 1970)- an "ordinary Rinzai Zen temple priest"- with Nishimura's running commentary, and a useful introduction by Bardwell Smith which underlines the paradox of tension and harmony characterizing Zen Buddhist monastic life. Taken as a whole, from its appreciative Foreword by Zenkei Shibayama to its Glossary, the book provides a helpful counterpoint to the standard popular work in this area, D.