Copyright by Sadie Nickelson-Requejo 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phone-Tapping Revelations Shock Mijas Mayor and Council

FREE COPY BREXIT THE NEWSPAPER FOR SOUTHERN SPAIN Costa Brits join Spaniards for Official market leader Audited by PGD/OJD London march March 29th to April 4th 2019 www.surinenglish.com As the UK’s exit from the EU remains unclear, News 2 Health & Beauty 42 Comment 20 Sport 48 residents support calls Lifestyle 22 My Home 53 What To Do 34 Classified 56 for a people’s vote P18 in English Food & Drink 39 Time Out 62 The historic Willow steamboat partially sank Coín has dumped in Benalmádena marina this week due to the enough sewage to rough sea. :: SUR fill a reservoir, says investigation The inquiry into the disposal of polluted water in Nerja and Coín throws up eye-watering figures P6 A third of colon cancer deaths could have been prevented. Residents are urged to take up health service’s screening offer P46 Under the spell of San Miguel de Allende. Andrew Forbes travels to Mexico for this month’s Travel Special P22-25 SPORT Malaga return to league THE COAST FALLS VICTIM TO THE WAVES action tonight after a 1-0 victory over Nàstic brought smiles back to the fans’ Beaches have been battered just two weeks before tourists flock in for Easter P2&3 faces at the weekend P48&49 Phone-tapping revelations shock Mijas mayor and council :: AGENCIA LOF Events in the minority Ciudadanos count, after the director of the coun- It’s not yet known who is council of Mijas took a surprising cil-owned broadcaster was removed, turn this week when it emerged that recently raised the alarm. -

Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos Nº 337-338, Julio-Agosto 1978

CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS MADRID JULIO-AGOSTO 1978 337-338 CUADERNOS HISPANO AMERICANOS DIRECTOR JOSÉ ANTONIO MARAVALL JEFE DE REDACCIÓN FÉLIX GRANDE HAN DIRIGIDO CON ANTERIORIDAD ESTA REVISTA PEDRO LAIN ENTRALGO LUIS ROSALES DIRECCIÓN, SECRETARIA LITERARIA Y ADMINISTRACIÓN Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación Avenida de los Reyes Católicos Teléfono 244 06 00 MADRID CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS Revista mensual de Cultura Hispánica Depósito legal: M 3875/1958 DIRECTOR JOSÉ ANTONIO MARAVALL JEFE DE REDACCIÓN FÉLIX GRANDE 337-338 DIRECCIÓN, ADMINISTRACIÓN Y SECRETARIA Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación Avda. de los Reyes Católicos Teléfono 244 06 00 MADRID INDICE NUMEROS 337-338 (JULIO-AGOSTO 1978) HOMENAJE A CAMILO JOSE CELA Páginas JOSE GARCIA NIETO: Carta mediterránea a Camilo José Cela ... 5 FERNANDO QUIÑONES: Lo de Casasana 13 HORACIO SALAS: San Camilo 1936-Madrid. San Rómulo 1976-Bue- nos Aires 17 PEDRO LAIN ENTRALGO: Carta de un pedantón a un vagabundo por tierras de España 20 JOSE MARIA MARTINEZ CACHERO: El septenio 1940-1946 en la bi bliografia de Camilo José Cela : 34 ROBERT KIRSNER: Camilo José Cela: la conciencia literaria de su sociedad • 51 PAUL ILIE: La lectura del «vagabundaje» de Cela en la época pos franquista 61 EDMOND VANDERCAMMEN: Cinco ejemplos del ímpetu narrativo de Camilo José Cela 81 JUAN MARIA MARIN MARTINEZ: Sentido último de «La familia de Píí ^C'tirii DtJ3tt&¡> Qn JESUS SANCHEZ LOBATO: La adjetivación "en «La familia de Pas cual Duarte» 99 GONZALO SOBEJANO: «La Colmena»: olor a miseria 113 VICENTE CABRERA: En busca de tres personajes perdidos en «La Colmena» 127 D. W. McPHEETERS: Tremendismo y casticismo 137 CARMEN CONDE: Camilo José Cela: «Viaje a la Alcarria» 147 CHARLES V. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Brad a Mante

B radA mante Revista de Letras, 1 (2020) Hablo de aquella célebre doncella la cual abatió en duelo a Sacripante. Hija del duque Amón y de Beatriz, era muy digna hermana de Rinaldo. Con su audacia y valor asombra a Carlos y Francia entera aplaude su coraje, que en más de una ocasión quedó probado, en todo comparable al de su hermano. Orlando furioso II, 31 B radA mante Revista de Letras, 1 (2020) | issn 2695-9151 BradAmante. Revista de Letras Dirección Basilio Rodríguez Cañada - Grupo Editorial Sial Pigmalión José Ramón Trujillo - Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Comité científico internacional M.ª José Alonso Veloso - Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Carlos Alvar - Université de Genève (Suiza) José Luis Bernal Salgado - Universidad de Extremadura Justo Bolekia Boleká - Universidad de Salamanca Rafael Bonilla Cerezo - Universidad de Córdoba Randi Lise Davenport - Universidad de Tromsø (Noruega) J. Ignacio Díez - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Ángel Gómez Moreno - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Fernando González García - Universidad de Salamanca Francisco Gutiérrez Carbajo - Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia Javier Huerta Calvo - Universidad Complutense de Madrid José Manuel Lucía Megías - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Karla Xiomara Luna Mariscal - El Colegio de México (México) Ridha Mami - Université La Manouba (Túnez) Fabio Martínez - Universidad del Valle (Colombia) Carmiña Navia Velasco - Universidad del Valle (Colombia) José María Paz Gago - Universidade da Coruña José Antonio Pascual Rodríguez - Real Academia -

Curriculum Vitae of John Eusebio Klingemann

CURRICULUM VITAE OF JOHN EUSEBIO KLINGEMANN ASU Station #10897 San Angelo, Texas 76909 325-942-2114 Work [email protected] Education Ph.D. University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 2008 B.A. Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas, 1997 M.A. Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas, 2002 Teaching Experience Department of History – Angelo State University (Associate Professor) HIST 6350 Contemporary Mexico HIST 6351 U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (online) HIST 4370 Capstone: Historical Research and Methodology HIST 4360 Slavery in Latin America HIST 4351 Mexico Since Independence HIST 4313 U.S. – Mexico Borderlands HIST 3355 Latin America to 1800 HIST 3356 Latin America Since 1800 MAS 2301 Introduction to Mexican American Studies HIST 1302 United States History 1865 to the Present (face-to-face and online) HIST 1301 United States History to 1865 USTD 1201 Critical Thinking GS 1181 United States History on Film (Signature Course Freshman College) Department of History – University of Texas Permian Basin (Guest Assistant Professor) HIST 6314 Latin America Department of History – University of Arizona HIST 369 Mexico Since Independence (Teaching Assistant) HIST 361 The U.S.-Mexico Border Region (Instructor) Borderlinks – Tucson, Arizona HISTORY History of Mexico (Instructor) Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences – Sul Ross State University 3309 History of Texas (Instructor) 1 Work Experience 2019-Present Dean, College of Arts and Humanities, Angelo State University 2014-2019 Department Chair, Department of History, Angelo State University 2015-2016 Interim Department Chair, Department of Communication and Mass Media, Angelo State University 2019-Present Professor, Department of History, Angelo State University 2015-2019 Associate Professor, Department of History, Angelo State University 2008-2015 Assistant Professor, Department of History, Angelo State University 2007-2008 Professional Specialist in History, Department of History, Angelo State University Languages Proficient in English and Spanish. -

Catalogoqueleopedrodevaldivia40.Pdf

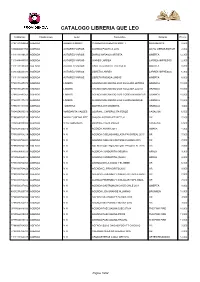

CATALOGO LIBRERIA QUE LEO CodBarras Clasificacion Autor Titulo Libro Editorial Precio 7798141020454 AGENDA ALBERTO MONTT CUADERNO ALBERTO MONTT MONOBLOCK 8,500 1000000001709 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS AGENDA POLITICA 2012 OCHO LIBROS EDITOR 2,900 1111111199121 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS DIARIO NARANJA ARTISTA OMERTA 12,300 1111444445551 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS IMANES LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 2,900 1111111198988 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA GRANATE CALCULO OMERTA 8,200 3333344443330 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 6,900 1111111198995 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA ROSADA LINEAS OMERTA 8,500 7798071447376 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LETRAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447390 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LLUVIA GRANICA 10,000 7798071447352 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BANDERAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447338 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BOSQUE GRANICA 10,000 7798071444399 AGENDA . MAITENA MAITENA 007 MAGENTA GRANICA 1,000 7804654930019 AGENDA MARGARITA VALDES JOURNAL, CAPERUCITA FEROZ VASALISA 6,500 7798083702128 AGENDA MARIA EUGENIA PITE CHUICK AGENDA PERPETUA VR 7,200 7804654930002 AGENDA NICO GONZALES JOURNAL PIZZA PALIZA VASALISA 6,500 7804634920016 AGENDA N N AGENDA AMAKA 2011 AMAKA 4,900 7798083704214 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO ANILLADA PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704221 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE FLORES 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704238 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 9789568069025 AGENDA N N AGENDA CONDORITO (NEGRA) ORIGO 9,900 9789568069032 AGENDA -

Bob Howard: the Laundry Series

Bob Howard: The Laundry Series free short stories by Charles Stross Table of Contents The Concrete Jungle..........................................1 Down on the Farm...........................................50 Overtime..........................................................72 Equoid..............................................................87 0 The Concrete Jungle I manage to pull on a sweater and jeans, tie my shoelaces, and get my ass downstairs just before by Charles Stross the blue and red strobes light up the window http://www.antipope.org/charlie/ above the front door. On the way out I grab my emergency bag — an overnighter full of stuff that Andy suggested I should keep ready, just in The death rattle of a mortally wounded case — and slam and lock the door and turn telephone is a horrible thing to hear at four around in time to find the cop waiting for me. o'clock on a Tuesday morning. It's even worse Are you Bob Howard? when you're sleeping the sleep that follows a Yeah, that's me. I show him my card. pitcher of iced margueritas in the basement of the Dog's Bollocks, with a chaser of nachos and If you'll come with me, sir. a tequila slammer or three for dessert. I come to, Lucky me: I get to wake up on my way in to sitting upright, bare-ass naked in the middle of work four hours early, in the front passenger the wooden floor, clutching the receiver with seat of a police car with strobes flashing and the one hand and my head with the other — purely driver doing his best to scare me into catatonia. -

From Tomóchic to Las Jornadas Villistas: Literary and Cultural Regionalism in Northern Mexico

From Tomóchic to Las Jornadas Villistas: Literary and Cultural Regionalism in Northern Mexico by Anne M. McGee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Romance Languages and Literatures: Spanish) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Gareth Williams, Chair Associate Professor Cristina Moreiras-Menor Associate Professor Gustavo Verdesio Assistant Professor Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes ____________________________© Anne M. McGee____________________________ All rights reserved 2008 Dedication To my first friend, teacher, and confidant, Patricia Ann McGee, otherwise known as, Mom. ii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my advisor and mentor Gareth Williams who has guided me throughout my graduate career. Without his advice, understanding, and suggestions, I may have never realized this project to completion. It was he who introduced me to the work of Nellie Campobello, and who filled my first summer reading list with numerous texts on Pancho Villa and the Mexican Revolution. I appreciate Gareth for always being frank, and pushing me to improve my work. I have always counted on and appreciated his direct and honest critique. In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to the other members of my committee. Cristina Moreiras-Menor has been both my professor and friend from my very first year in graduate school. She has patiently listened to my ideas, and helped me immensely. I will also never forget my first course, “Rethinking Indigeneities” with Gustavo Verdesio. Whether in class or over a cup of coffee (or other beverage), Gustavo has always been ready and willing to participate in the type of lively discussions that have shaped my work at the University of Michigan. -

Tom Mahoney Research Materials on Pancho Villa and the Mexican Revolution, 1890-1981

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81g0rs2 No online items Finding Aid for the Tom Mahoney research materials on Pancho Villa and the Mexican Revolution, 1890-1981 Beth Ann Guynn Finding Aid for the Tom Mahoney 2001.M.20 1 research materials on Pancho Villa and the Mexican Revolut... Descriptive Summary Title: Tom Mahoney research materials on Pancho Villa and the Mexican Revolution Date (inclusive): 1890-1981 Number: 2001.M.20 Creator/Collector: Mahoney, Tom Physical Description: 6.74 Linear Feet(8 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The Tom Mahoney Research Materials on Pancho Villa and the Mexican Revolution comprises materials related to an unpublished book by Mahoney with the working title "P-a-n-c-h-o V-i-l-l-a: Bandit...Rebel...Patriot...Satyr," which he began working on in the late 1920s. Included is a partial typescript for the book and a paste-up of photographic illustrations. Research materials include hand- or type-written notes and transcriptions; extensive files of clippings from revolution-era and post-revolution Mexican and American newspapers; related manuscripts and publications and research-related correspondence. Also included are research files on topics of interest to Mahoney, many of which relate to his book and magazine publications, such as The Great Merchants and The Story of Jewelry. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. -

The Carranza-Villa Split and Factionalism in the Mexican Revolution, 1913--1914

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1986 Prelude to fratricide| The Carranza-Villa split and factionalism in the Mexican Revolution, 1913--1914 Joseph Charles O'Dell The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation O'Dell, Joseph Charles, "Prelude to fratricide| The Carranza-Villa split and factionalism in the Mexican Revolution, 1913--1914" (1986). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3287. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3287 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUB SISTS. ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE : 19 86 PRELUDE TO FRATRICIDE: THE CARRANZA-VILLA SPLIT AND FACTIONALISM IN THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION, 1913-1914 by Joseph Charles O'Dell, Jr. B.A., University of Montana, 1984 Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1986 pproved by: Examiners Dean, GraduaterTschool ^ $4 Date UMI Number: EP36375 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Hacking the PSP™

http://videogames.gigcities.com 01_778877 ffirs.qxp 12/5/05 9:29 PM Page i Hacking the PSP™ Cool Hacks, Mods, and Customizations for the Sony® PlayStation® Portable Auri Rahimzadeh 01_778877 ffirs.qxp 12/5/05 9:29 PM Page i Hacking the PSP™ Cool Hacks, Mods, and Customizations for the Sony® PlayStation® Portable Auri Rahimzadeh 01_778877 ffirs.qxp 12/5/05 9:29 PM Page ii Hacking the PSP™: Cool Hacks, Mods, and Customizations for the Sony® PlayStation® Portable Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 10475 Crosspoint Boulevard Indianapolis, IN 46256 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2006 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada ISBN-13: 978-0-471-77887-5 ISBN-10: 0-471-77887-7 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1B/SR/RS/QV/IN No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4355, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

Creación De Pancho Villa Por Nellie Campobello En Los Apuntes Sobre La Vida Militar De Francisco Villa (1940)

Cuando la Historia se hace historia: (re)creación de Pancho Villa por Nellie Campobello en Los apuntes sobre la vida militar de Francisco Villa (1940) Jeromine FRANÇOIS Université de Liège RESUMEN Este artículo lleva a cabo un análisis del texto de la escritora Mexicana Nellie Campobello, Los apuntes sobre la vida militar de Francisco Villa, en el cual el personaje histórico y su protagonismo en la Revolución mexicana pasan a convertirse en una historia novela en la que realidad y ficción rompen sus fronteras. Palabras clave: Nellie Campobello, Pancho Villa, Revolución mexicana, biografía, ficción. When the History does history to itself: (re) Pancho Villa's creation for Nellie Campobello in Los apuntes sobre la vida militar de Francisco Villa (1940) ABSTRACT This article carries out an analysis of the text of the writer Mexicana Nellie Campobello, Los apuntes sobre la vida militar de Francisco Villa, in which the historical personage and his protagonism in the Mexican Revolution happen to turn into a history writes novels in that reality and fiction break his borders. Key words: Nellie Campobello, Pancho Villa, Mexican Revolution, Biography, Fiction. Introducción No son pocas las afinidades que relacionan a Nellie Campobello con el revolucionario Pancho Villa. Contemporánea suya, la madre de Campobello era villista y transmitió a su hija su admiración por el guerrero revolucionario. Además, aunque puedan resultar anecdóticos, los parecidos vitales entre la escritora y Villa no dejan de ser curiosos. Los dos son originarios de Durango y, además, ambos experimentaron un cambio onomástico: Doroteo Arango eligió el seudónimo de Francisco Villa (Berumen, 2006, 34) y Francisca Moya Luna adquirió el seudónimo de Nellie Campobello hacia 1923 (Bautista Aguilar, 2007, 12).