American Protestants and the Vietnam War A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Celeste Birkey

Celeste Birkey A little bit of information about Celeste: Celeste began attending Meadowbrook Church in 1990 and became a member August 2000. With her marriage to Joe Birkey in 2005, she has dual membership with both Meadowbrook and her husband’s church, East Bend Mennonite. She has participated on Meadowbrook mission trips twice to El Salvador and once to Czech Republic. Celeste grew up in the Air Force. Her father was a Master Sargent in the Air Force. Celeste and her mother moved with her father as his assignments allowed and took them around the world. She has lived or traveled to about 20 countries during her lifetime. During a trip to Israel, she was baptized in the Jordan River. Favorite Hymn- “I don’t have a favorite song or hymn, there are so many to choose from. I really enjoy the old hymns of the church. They give me encouragement in my walk with the Lord. The hymns also give me valuable theology lessons and advice from the saints of previous generations [hymn authors].” Celeste explains that hymnal lessons provide systematic theology in that it teaches her how to have intimacy with God, to know who God is, how she can relate to Him, what is required for salvation, what grace from God means, and how to walk in the spirit. Favorite Scripture- Psalm 125:1-2 “They that trust in the Lord shall be as Mount Zion which cannot be removed, but abideth forever. As the mountains are round about Jerusalem, so the Lord is round about His people from henceforth even forever.” This verse gives Celeste comfort in knowing God surrounds her with protection forever. -

The Ecumenical Movement and the Origins of the League Of

IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by James M. Donahue __________________________ Mark A. Noll, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana April 2015 © Copyright 2015 James M. Donahue IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 Abstract by James M. Donahue This dissertation traces the origins of the League of Nations movement during the First World War to a coalescent international network of ecumenical figures and Protestant politicians. Its primary focus rests on the World Alliance for International Friendship Through the Churches, an organization that drew Protestant social activists and ecumenical leaders from Europe and North America. The World Alliance officially began on August 1, 1914 in southern Germany to the sounds of the first shots of the war. Within the next three months, World Alliance members began League of Nations societies in Holland, Switzerland, Germany, Great Britain and the United States. The World Alliance then enlisted other Christian institutions in its campaign, such as the International Missionary Council, the Y.M.C.A., the Y.W.C.A., the Blue Cross and the Student Volunteer Movement. Key figures include John Mott, Charles Macfarland, Adolf Deissmann, W. H. Dickinson, James Allen Baker, Nathan Söderblom, Andrew James M. Donahue Carnegie, Wilfred Monod, Prince Max von Baden and Lord Robert Cecil. -

History of the Christian Flag

History of the Christian Flag The Christian Flag is a flag designed in the early 20th century to represent all of Christianity and Christendom, and has been most popular among Protestant churches in North America, Africa and Latin America. The flag has a white field, with a red Latin cross inside a blue canton. The shade of red on the cross symbolizes the blood that Jesus shed on Calvary. The blue represents the waters of baptism as well as the faithfulness of Jesus. The white represents Jesus' purity. In conventional vexillology, a white flag is linked to surrender, a reference to the Biblical description of Jesus' non-violence and surrender to God. The dimensions of the flag and canton have no official specifications. The Christian flag is not tied to any nation or denomination; however, non-Protestant branches of Christianity do not often fly it. According to the Prayer Foundation, the Christian flag is uncontrolled, independent, and universal. Its universality and free nature is meant to symbolize the nature of Christianity. According to Wikipedia and other online sources, the Christian flag dates back to an impromptu speech given by Charles C. Overton, a Congregational Sunday school superintendent in New York, on Sunday, September 26, 1897. The Union Sunday school that met at Brighton Chapel Coney Island had designated that day as Rally Day. The guest speaker for the Sunday school kick-off didn't show up, so Overton had to wing it. Spying an American flag near (or draped over) the podium (or piano), he started talking about flags and their symbolism. -

WELS Flag Presentation

WELS Flag Presentation Introduction to Flag Presentation The face of missions is changing, and the LWMS would like to reflect some of those changes in our presentation of flags. As women who have watched our sons and daughters grow, we know how important it is to recognize their transition into adulthood. A similar development has taken place in many of our Home and World mission fields. They have grown in faith, spiritual maturity, and size of membership to the point where a number of them are no longer dependent mission churches, but semi- dependent or independent church bodies. They stand by our side in faith and have assumed the responsibility of proclaiming the message of salvation in their respective areas of the world. Category #1—We begin with flags that point us to the foundations of support for our mission work at home and abroad. U.S.A. The flag of the United States is a reminder for Americans that they are citizens of a country that allows the freedom to worship as God’s Word directs. May it also remind us that there are still many in our own nation who do not yet know the Lord, so that we also strive to spread the Good News to the people around us. Christian Flag The Christian flag symbolizes the heart of our faith. The cross reminds us that Jesus shed his blood for us as the ultimate sacrifice. The blue background symbolizes the eternity of joy that awaits us in heaven. The white field stands for the white robe of righteousness given to us by the grace of God. -

Wesley United Methodist Church to Know Christ

Wesley United Methodist Church To Know Christ - To Make Him Known Traditional Worship Service Contemporary Worship Service Main Sanctuary WMC 120 North Avenue A 60 North Avenue A 8:30 am 10:45 am Sunday School 9:40 OPPORTUNITIES FOR GROWING AND SHARING SUNDAY, JULY 6 8:30 am Worship Service (Sanctuary) 9:30 am Coffee fellowship (Wesley Hall) 9:40 - 10:30 am Sunday School 10:15 am Coffee Fellowship (Wesley Ministry Center) 10:45 am Contemporary Worship Service (Wesley Ministry Center) 6:00 pm Beth Moore study (Wesley Hall) MONDAY, JULY 7 6:00 pm Lambs of God Board mtg (WMC) 8:30 pm High School Girls Group (WMC) TUESDAY, JULY 8 8:00 am Communion Service (Sanctuary) 8:30 am Ladies Bible Study Group (library) WEDNESDAY, JULY 29 9:00 am Rug Sewing (Fellowship Hall) THURSDAY, JULY 10 8:00 am PEO (Wesley Hall) 7:00 pm Praise Band Practice (WMC) FRIDAY, JULY 11 5:30 - 6:30 pm AA Meeting (Fellowship Hall) 6:00pm - midnight Scrapbook Club SATURDAY, JULY 12 10:00 - 11:00 am AA Meeting (Fellowship Hall) ATTENDANCE REPORT June 29, 2014 A note from the office… Please remember to update the office when you have an address, 8:15 - 162 10:30 - 198 Total: 360 Sunday School 53 phone number, or email change. COLLECTION ITEMS FOR JULY… Also if you would like to have flowers placed in the Can of tuna, macaroni, cream of mushroom soup and can of fruit... church or the ministry center celebrating a birthday, an- Your donation of these items support local families in need. -

The Maine Bugle 1894

r THE MAINE BUGLE. Entered at the Po$t Office, Rockland, Me., at Second-Ctati Matter. Campaign I. January, 1894. Call i Its echoing notes your memories shall renew From sixty-one until the grant! review. UBLISHED QUARTERLY, JANUARY, APRIL, JULY AND OCTOBER, AND WILL BE THE ORGAN OF THE " MEN OF MAINE " WHO SERVED IN THE WAR OF THE REBELLION. NO OTHER STATE HAS A PROUDER RECORD. IT WILL CONTAIN THE PROCEEDINGS OF THEIR YEARLY REUNIONS, MATTERS OF HISTORIC VALUE TO EACH REGI- MENT, AND ITEMS OF PERSONAL INTEREST TO ALL ITS MEMBERS. IT IS ALSO THE ORGAN OF THE CAVALRY SOCIETY OF THE ARMIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND WILL PUBLISH THE ANNUAL PROCEEDINGS OF THAT SOCIETY AND CONTRIBUTIONS FROM MEMBERS OF THE VARIOUS REGIMENTS NORTH AND SOUTH WHICH PARTICIPATED IN THE WAR OF THE REBELUON. PRICE ONE DOLLAR A YEAR, OR TWENTY-FIVE CENTS A CALL Editors, Committees from the Maine Regiments. Published by the Maine Association. Address, J. P. Cuxey, Treasurer, RoCKlAND, Mainb. L rs^^ A . A. 41228 Save Money. — Regular Subscribers and those not regular subscribers to the Bugle may, by ordering through us the periodicals for which they arc subscrib- ers, add Bf r.i.E at a greatly reduced price if not without cost. Thus if you wish, let us say, Cosmopolitan and Harper^s Monthly, send the money through this ofTice and we will add Bugle to the list without extra cost. Regular With Price Bugle Arena, *5-oo Army and Navy Journal, Atlantic Monthly, Blue and CIray, Canadian Sportsman, Cassel's Family Magazine, Century, Cosmopolitan, Current Literature, Decorator and Furnisher, Demorest's Family Magazine Fancier, Godey's Ladies' Book, Harper's Bazar or Weekly, Harper's Magazine, Harper's Young People, Home Journal, Horseman, Illustrated American, Journal of Military Service and Institution, Judge, Life, Lippincott's Magazine, Littell's Living Age, North American Review, New England Magazine, Outing, Popular Science Monthly, Public Opinion, Review of Reviews, Scicntiiic American, Supplement, Both, same address. -

Vacation Bible School Worship Express Script

Vacation Bible School Worship Express Script _________________________________________________________________________________________________________Page 1 of 18 Vacation Bible School Worship Express Script. "The Great Commission Express—A Mission Adventure of a Lifetime." Copyright © 2019 BAPTISTWAY PRESS®. Not to be sold. A ministry of the Baptist General Convention of Texas. www.baptistwaypress.org. These VBS materials are produced by BAPTISTWAY PRESS® based on materials developed by Park Cities Baptist Church, Dallas, Texas. Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, New International Version (North American Edition), copyright ©1973, 1978, 1984 by the International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. The Great Commission Express— A Mission Adventure of a Lifetime Suggested Elements of Worship for Children (Completed Grades 1-6) Scripture: Each day the Scripture passage chosen for the week will be read. It is important for children to understand the Scripture and learn how to apply the Bible truths to their everyday life. Children's departments are encouraged to review the unit scripture each day. Music: Music is a powerful medium to use with children. The praise songs suggested were chosen because of the simplicity of the words and the message. Children are literal learners. If other songs are chosen, remember to find Scripture-based songs without symbolism, if possible. The songs on the PowerPoint and the countdown video may be individually downloaded from www.godskidsworship.com. Click on the download tab to instantly download the suggested songs and countdown video. Choose countdown videos and choose Cool Dino with a Drink. The countdown video is a five- minute video that is fun, animated and energized. -

—Purposeful Living:“ Images of the Kingdom of God in Methodist

“Purposeful Living:” Images of the Kingdom of God in Methodist Sunday School Worship Jennifer Lynn Woodruff Duke University June 2002 The history of Methodism in America is closely tied to the history of Sunday School1 in America. And the history of Sunday School in America has been formed by the aims of Sunday School worship in America, although this connection often remains at the unconscious level. The aim of Sunday School from the beginning has been to communicate the Christian truth, particularly desired image of the Kingdom of God, in some form—and one of the most effective ways found to communicate and experience the outlines of that kingdom has been through the actions of worship. This paper will outline a brief history of images of the Kingdom of God in Sunday School worship in (white) American Methodism, focusing on the Methodist Episcopal Church and the Methodist Episcopal Church, South Official hymnals, songbooks, published orders of worship, prescriptive literature, and oral history2 have all formed part of this endeavor. Sunday school participants were at various times intended through their worship to be incorporated into the kingdom by being civilized, educated, uplifted, converted, challenged, molded, made into good citizens, enriched, deepened, enlightened, raised in consciousness, motivated, nurtured, and entertained—but they have never, ever been ignored. 1784-1844: Laying the Foundations 1790s-1820s: Theme: Assisting the disadvantaged Aim: Civilizing as Christians Orders and Resources: Simple hymns and prayers, otherwise unknown Audience: Unchurched 1 The Sunday School movement has also been known as Sabbath school, church school, and Christian education, for varying theological and social reasons. -

SOUTHERN UNION PATHFINDER CEREMONIES (1St Edition, 02-May-2019)

SOUTHERN UNION PATHFINDER CEREMONIES (1st Edition, 02-May-2019) FOREWORD This manual is a compilation of traditions and practices when performing Drill commands at Pathfinder events. It serves as a guideline to address many questions by conference club staff in how Pathfinders are to conduct ceremonies in or outside their churches. Traditionally, the Pathfinder Club has followed the standards based on the US Army manual FM 22-5 ‘Drill and Ceremonies’ and its current version, the FM 3-21.5. This guide intends to address information that has been passed as military standard and tradition but not described in the US Army Drill and Ceremonies manual. It also adds portions specific to Pathfinder Club activities to conform to these traditions. While researching sources we consulted various Pathfinder and military veteran organizations. For the veteran organizations we approached the Non Commissioned Officers Association (NCOA), the American Legion, and the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). And, although the latter are military focused organizations we must not forget that Pathfinders are not soldiers. It is the intention to teach respect and to honor the US flag and to conduct ceremonies in an orderly fashion in the manner that our God deserves. 2 CONTRIBUTORS The following people served in the committee or assisted in the preparation of this manual. A special thanks to Pastor Ken Rogers, Southern Union Pathfinder Director, for sponsoring this effort. Carolina Conference Larry Duchaine, Conference representative for Drill Florida Conference Alexis -

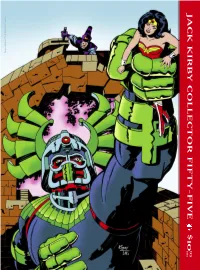

Tjkc55preview.Pdf

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FIFTY-FIVE $1095 IN THE US odrWmnT 21 CComics. DC ©2010 & TM Woman Wonder NEW BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS! NOW SHIPPING! SHIPS IN DEC.! CARMINE INFANTINO PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR CARMINE INFANTINO is the artistic and publishing visionary whose mark on the comic book industry pushed conventional bound- aries. As a penciler and cover artist, he was a major force in defining the Silver Age of comics, co-creating the modern Flash and resuscitating the Batman franchise in the 1960s. As art director and publisher, he steered DC Comics through the late 1960s and 1970s, one of the most creative and fertile periods in their long history. Join historian and inker JIM AMASH (Alter Ego magazine, Archie Comics) and ERIC NOLEN-WEATHINGTON (Modern Masters book series) as they document the life and career of Carmine Infantino, in the most candid and thorough interview this controversial living legend has ever given, lavishly illustrated with the incredible images that made him a star. CARMINE INFANTINO: PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR shines a light on the artist’s life, career, and contemporaries, and uncovers details about the comics industry never made public until now. The hardcover edition includes a dust jacket, custom endleaves, plus a 16-PAGE FULL-COLOR SECTION not found in the softcover edition. New Infantino cover inked by TERRY AUSTIN! (224-page softcover) $26.95 • (240-page hardcover with COLOR) $46.95 THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Face front, true believers! THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE is the ultimate repository of interviews with and mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! From his Soapbox to the box office, the Smilin’ One literally changed the face of comic books and pop culture, and this tome presents numerous rare and unpublished interviews with Stan, plus interviews with top luminaries of the comics industry, AND NOW including JOHN ROMITA SR. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR #63 All characters TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. $10.95 SUMMER 2014 THE ISSUE #63, SUMMER 2014 C o l l e c t o r Contents The Marvel Universe! OPENING SHOT . .2 (let’s put the Stan/Jack issue to rest in #66, shall we?) A UNIVERSE A’BORNING . .3 (the late Mark Alexander gives us an aerial view of Kirby’s Marvel Universe) GALLERY . .37 (mega Marvel Universe pencils) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .48 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) JACK F.A.Q.s . .49 (in lieu of Mark Evanier’s regular column, here’s his 2008 Big Apple Kirby Panel, with Roy Thomas, Joe Sinnott, and Stan Goldberg) KIRBY OBSCURA . .64 (the horror! the horror! of S&K) KIRBY KINETICS . .67 (Norris Burroughs on Thing Kong) IF WHAT? . .70 (Shane Foley ponders how Jack’s bad guys could’ve been badder) RETROSPECTIVE . .74 (a look at key moments in Kirby’s later life and career) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .82 (we go “under the sea” with Triton) CUT ’N’ PASTE . .84 (the lost FF #110 collage) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .86 (the return of the return of Captain Victory) UNEARTHED . .89 (the last survivor of Kirby’s Marvel Universe?) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .91 PARTING SHOT . .96 Cover inks: MIKE ROYER Cover color: TOM ZIUKO If you’re viewing a Digital Edition of this publication, PLEASE READ THIS: This is copyrighted material, NOT intended Spider-Man is the one major Marvel character we don’t cover this issue, but here’s a great sketch of Spidey that Jack drew for for downloading anywhere except our website or Apps.