A Vanishing Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song: A Portfolio of Recordings and Exegesis Qing (Lily) Chang Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide July 2017 Table of contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements List of tables and figures Part A: Sound recordings Contents of CD 1 Contents of CD 2 Contents of CD 3 Contents of CD 4 Part B: Exegesis Introduction Chapter 1 Historical context 1.1 History of Chinese art song 1.2 Definitions of Chinese contemporary art song Chapter 2 Performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.1 Singing Chinese contemporary art song 2.2 Vocal techniques for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.3 Various vocal styles for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.4 Techniques for staging presentations of Chinese contemporary art song i Chapter 3 Exploring how to interpret ornamentations 3.1 Types of frequently used ornaments and their use in Chinese contemporary art song 3.2 How to use ornamentation to match the four tones of Chinese pronunciation Chapter 4 Four case studies 4.1 The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Shang Deyi 4.2 I Love This Land by Lu Zaiyi 4.3 Lullaby by Shi Guangnan 4.4 Autumn, Pamir, How Beautiful My Hometown Is! by Zheng Qiufeng Conclusion References Appendices Appendix A: Romanized Chinese and English translations of 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix B: Text of commentary for 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix C: Performing Chinese contemporary art song: Scores of repertoire for examination Appendix D: University of Adelaide Ethics Approval Number H-2014-184 ii NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. -

Chapter Ii the Development of China Panda Diplomacy A

CHAPTER II THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHINA PANDA DIPLOMACY This chapter discusses the development of China Panda Diplomacy. The researcher will explain the symbolism of Panda. In the other hand, the researcher will explore the stages of Panda Diplomacy and mentioning the step of the giant Panda loan breeding process. Last but not least, the writer will mention the countries that received the Panda. A. THE SYMBOLISM OF PANDA China was known as one of the oldest ancient in the earth. Besides its famous landmark of the Great Wall, China owns a cute animal named the Giant Panda, Ailuropoda Melanoleuca (Xianmeng Qiu, Susan A. Mainka, 1993). From the Chinese perspective, Panda is a symbol of peace and friendship. They have a gentle temperament and aren’t known for attacking others. This animal is also believed to have powers to combat evil spirits (Wang, 2017). There some province in China assumes that giant panda is a symbol of luck. The color contrast of giant panda equated as the mythology of Yin and Yang or means as equality that reflected the equality of life. The Pandas are seen as a symbol of co- operation between China and the receiving countries (Hinderson, 2017). Scholars acknowledge that culture is as important a politics, military, and economic as an element in influencing the development of a nation’s foreign policy (Hu, 2013). Buckingham, et al. (2013) stated that the Panda represents a fascinating soft-power resource. The panda offers a softer animal symbol for China compared to those of its past – the red dragon- and it is dealing with the natural beauty of the country. -

US Zoo to Return Beloved Giant Pandas to China 27 March 2019

US zoo to return beloved giant pandas to China 27 March 2019 The species was threatened with extinction when the zoo teamed up with China 25 years ago as part of a conservation program. Today, pandas are listed as a vulnerable species. That means that while their survival is still threatened, conservation efforts have helped reduce their danger of extinction. "We understand that pandas are beloved around the world, including by our staff, volunteers and millions of annual guests," said San Diego Zoo director Dwight Scott. "We are planning a fitting celebration next month Female panda Bai Yun (R) and male panda Gao Gao (L) for Bai Yun and Xiao Liwu that includes a big thank view each other through a screened gate between their you to the Chinese people for their continued exhibits on April 15, 2011 at the San Diego Zoo partnership and our combined conservation accomplishments in helping to save this amazing species." Two giant pandas that have been a star attraction © 2019 AFP at the San Diego Zoo for decades will soon be returned home to China, officials announced. Bai Yun, the 27-year-old female giant panda, and her son, six-year-old Xiao Liwu, will be repatriated to their ancestral homeland in late April. "Although we are sad to see these pandas go, we have great hopes for the future," Shawn Dixon, chief operating officer for San Diego Zoo Global, said in a statement issued Monday. "Working with our colleagues in China, San Diego Zoo Global is ready to make a commitment for the next stage of our panda program." The pandas had been on loan to the zoo as part of a long-term conservation agreement that is coming to an end. -

Cloning Noah's

n late November a humble Iowa cow is slated to give birth to the world’s first cloned endangered species, a baby bull to be named Noah. Noah is a gaur: a member of a species of large oxlike animals that are now rare in their homelands of India, In- Idochina and southeast Asia. These one-ton bovines have been hunted for sport for generations. More recently the gaur’s habitats of forests, bamboo jungles and grasslands have dwindled to the point that only roughly 36,000 are thought to remain in the wild. The World Conservation Union–IUCN Red Data Book lists the gaur as endangered, and trade in live gaur or gaur products—whether horns, hides or hooves—is banned by the Convention on Interna- tional Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). But if all goes as predicted, in a few weeks a spindly-legged little Noah will trot in a new day in the conservation of his kind as well as in the preservation of many other endangered species. Perhaps most important, he will be living, mooing proof that one animal can carry and give birth to the exact genetic du- plicate, or clone, of an animal of a different species. And Noah will be just the first creature up the ramp of the ark of endangered species that we and other scientists are currently attempting to clone: plans are under way to clone the African bongo antelope, the Sumatran tiger and that favorite of zoo lovers, the reluctant-to-reproduce giant panda. Cloning could also reincarnate some spe- cies that are already extinct—most immediately, perhaps, the bucardo mountain goat of Spain. -

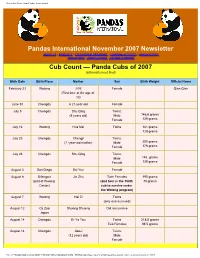

November News from Pandas International

November News from Pandas International Pandas International November 2007 Newsletter ABOUT US :: PRODUCTS :: EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS :: LEARNING ACTIVITIES :: PANDA PHOTOS DONATE NOW :: ADOPT A PANDA :: BECOME A MEMBER Cub Count — Panda Cubs of 2007 (information not final) Birth Date Birth Place Mother Sex Birth Weight Official Name February 23 Wolong Ji Ni Female Qian Qian (First time at the age of 13) June 30 Chengdu A 21-year-old Female July 5 Chengdu Shu Qing Twins: (8 years old) Male 146.5 grams Female 129 grams July 16 Wolong Hua Mei Twins 161 grams 129 grams July 23 Chengdu Chengji Twins: (7 -year-old mother) Male 200 grams Female 176 grams July 23 Chengdu Shu Qing Twins: Male 146. grams Female 129 grams August 3 San Diego Bai Yun Female August 6 Bifengxia Jin Zhu Twin Females 190 grams (part of Wolong (2nd twin is the 100th 70 grams Center) cub to survive under the Wolong program) August 7 Wolong Hai Zi Twins (only one survived) August 12 Oji Zoo Shuang Shuang Did not survive Japan August 14 Chengdu Er Ya Tou Twins 218.5 grams Two Females 98.5 grams August 14 Chengdu Jiaozi Twins: (12 years old) Male Female file:///**WORKING%20FOLDER/**CURRENT%20WORK/PAND...TTERS/2007/November%202007/nov07-newsletter.html (1 of 6)10/26/07 3:17 PM November News from Pandas International August 18 Wolong Gong Zhu Twins: 168 grams Males 179 grams August 23 Schoenbrunn Yang Yang Twins 3.5 ounces Zoo, Vienna, (first time mother) (only one survived) 3.9 inches Austria August 24 Wolong Long Xin Twins September 14 Wolong Ye Ye Twins Breeding pens at Wolong Suzanne Braden with Qing Qing, first cub of 2007, in July 2007. -

Aaa Panda Is Born Mongolian Mummies Lighthouse Postcards

3 aaa panda is born 6 mongolian mummies 8 lighthouse postcards Smithsonian Institution SCIENCE, HISTORY AND THE ARTS NUMBER 11 · WINTER 2006 smithsonian online Electricity on film. Since the 1930s, the distinctive images disseminated by the Wash- ington, D.C.-based organization Science Service have captured the attention of newspa- per and magazine readers worldwide. These sci- ence-focused images and their concise captions helped forge a broader understanding and appreci- ation of the many scientific and technological number 11 · winter 2006 achievements made in the last 80 years. A new Web site from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Published quarterly by the Smithsonian Office of Public Affairs, Smithsonian Institution American History features an eye-grabbing selec- Building, Room 354, MRC 033, P.O. Box tion of Science Service images related to electricity 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, for and dating from the 1930s to the 1960s. Accompa- Smithsonian Contributing Members, scholars, nied by their original captions, the photos in this educators, museum personnel, libraries, online archives are presented exactly as they ap- journalists and others. To be added to the mailing list or to request this publication in peared in period publications. Organized under an accessible format, call (202) 633-5181 dozens of subject headings, such as batteries, ca- (voice) or (202) 357-1729 (TTY). bles, cameras, computer art, lighting, electron John Barrat, Editor tubes, fiber optics, fire alarms, lasers, recordings, stratovision and television, this Web site is a visual Colleen Perlman, Assistant Editor primer on the development and application of Evelyn S. Lieberman, Director of electronics in modern life. -

Frozen Zoo May Hold Hope for Saving the Northern White Rhino

Frozen Zoo may hold hope for saving the northern white rhino By TONY PERRY JANUARY 23, 2015, 7:07 PM | REPORTING FROM SAN DIEGO ola is eating her morning meal of apples and grain and appears ready to take her N antibiotic pills. After feeling poorly for a couple of weeks, she is moving around. This is welcome news to Nola's devoted keepers at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. She is one of only five northern white rhinos left on Earth: three of the others are in a preserve in Kenya, and one is in a zoo in the Czech Republic. Nola's recent illness, coming just weeks after the unanticipated death of Angalifu, the park's male northern white rhino, was a pointed reminder of the fragility of her species. At 40, even with care, Nola is near the end of her expected life span, and breeding is no longer seen as an option. Efforts in Kenya to mate the male and the two females have been unsuccessful. But scientists working for the zoo's Institute for Conservation Research say hope may yet exist for the northern white rhino: futuristic technology that might allow it to make a comeback even after the remaining animals are gone. The strategy — a long shot, researchers acknowledge — involves frozen specimens of reproductive material and a surrogate rhino mother from a different subspecies. "You have to be optimistic, but you have to be willing to accept that you're going to fail sometimes," said Barbara Durrant, director of reproductive physiology at the institute. -

Pandas International September 2009 Newsletter

Pandas International September 2009 Newsletter You're receiving this announcement because you have signed up as a Panda Pal. Not interested anymore? Unsubscribe. Having trouble viewing this email? View it in your browser . DONATE NOW :: ADOPT A PANDA :: SPONSOR A PANDA :: BECOME A MEMBER Some original material reprinted by Pandas International's Newsletter is used without editing for accepted English usage. Summer, a time of births and birthdays San Diego Zoo's giant panda, Bai Yun, gives birth to a healthy cub Just before 5 a.m. on August 5, 2009, Bai Yun gave birth to what the zoo's senior research technician Suzanne Hall called a "vigorous, squawking" cub. For about 24 hours prior to the birth, Bai Yun had been restless, alternating between sleep and bouts of nest-building, Hall wrote on the zoo's blog. The cub's gender is not yet known. Bai Yun (seen here in an archived photo) Bai Yun is described by zoo staff as an is proving to be a great mother once again. excellent, attentive mother; she's given birth Read the complete story >> to four other cubs (Hua Mei, Mei Sheng, Su Lin and Zhen Zhen) since arriving at the zoo See video of cub's birth >> as part of a scientific exchange with China in 1996. Not to be forgotten, Zhen Zhen and Su Lin celebrate their birthdays at the San Diego Zoo Giant pandas Zhen Zhen and Su Lin celebrated their birthdays at the San Diego Zoo Monday, August 3rd, with tiered ice cakes filled with their favorite treats -- apples, carrots and bamboo. -

Giant Panda Zoo Awards 2014

Giant Panda Zoo Awards 2014 大熊猫动物园奖 www.GiantPandaZoo.com www.DaXiongMaoDongWuYuan.com Xing Hui - Pairi Daiza 星徽 - 天堂动物园 Welcome to the introduction magazine about the third edition of the Annual Giant Panda Zoo Awards organ- ised by www.GiantPandaZoo.com. As a young panda fan, looking around for information about my favorite animal, I launched the website in 2000. My passion for pandas started during many visits to my Belgian hometown zoo in the summer of 1987. Wan Wan & Xi Xi were on a short-term loan at the Zoo of Antwerp from Xian Zoo. In the same year, Chuan Chuan & Su Su from the Chengdu Zoo visited the Netherlands, Yun Yun & Ling Ling created new pandamonium in New York and in Tampa, U.S.A., but the visit of 1987 with the most impact might have been the one of Basi & Yuan Yuan from Fuzhou Panda World to the San Diego Zoo. Adventure World Wakayama in Japan was the first foreign institution to sign a longterm giant panda breeding loan. The San Diego Zoo was the first Western zoo to sign such a contract. Bai Yun gave birth to Hua Mei on August 21, 1999. The online pandamonium started and Hua Mei was the first foreign born giant panda to move back to her parents native country. This year, I completed my world tour and have visited all countries worldwide with giant pandas and one of Hua Mei's cubs, Hao Hao, moved to Belgium with her mate Xing Hui. Pairi Daiza was the first foreign zoo to sign a 15-year panda breeding loan. -

An Introduction to Zoological Multiplicity in the Modern American Zoo Emily D

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 Menageries Multiple: An Introduction to Zoological Multiplicity in the Modern American Zoo Emily D. Gratke Scripps College Recommended Citation Gratke, Emily D., "Menageries Multiple: An Introduction to Zoological Multiplicity in the Modern American Zoo" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 1059. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1059 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MENAGERIES MULTIPLE: AN INTRODUCTION TO ZOOLOGICAL MULTIPLICITY IN THE MODERN AMERICAN ZOO by EMILY D. GRATKE SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR PERINI PROFESSOR WILLIAMS APRIL 21, 2017 i CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION Methodology and Term Definition CHAPTER ONE. Zoological Multiplicity through Time The Emergence of Pet Keeping The Growth of the American Zoo The Development of the Modern Animal Rights Movement Moving on to Modern Multiplicity CHAPTER TWO. Animals in Action: Contemporary Manifestations of Multiplicity The Perception of the Zoogoer The Perception of the Activist The Perception of the Zoo The Meaning of Multiplicity CHAPTER THREE. The Effects of Zoological Multiplicity CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK Bibliography ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to first thank Professor Perini for her continuous support, guidance, and mentorship throughout this project. I would also like to thank Professor Williams for her assistance in the reading and editing processes, as well as Professor de Laet for her help in shaping the framework of my thesis. -

Pandas International November 2009 Newsletter

Pandas International November 2009 Newsletter You're receiving this announcement because you have signed up as a Panda Pal. Not interested anymore? Unsubscribe. Having trouble viewing this email? View it in your browser . DONATE NOW :: ADOPT A PANDA :: SPONSOR A PANDA :: BECOME A MEMBER Some original material reprinted by Pandas International's Newsletter is used without editing for accepted English usage. Australia’s Big News, Wang Wang and Fu Ni Have Arrived! Pandas Settle Into New Enclosure at Adelaide Zoo AARON MACDONALD Giant pandas Wang Wang and Fu Ni are settling into their new enclosure at Adelaide Zoo without a hitch. The giant pandas arrived on Saturday morning to much fanfare and spent the weekend curiously exploring the indoor section of their $8 million digs. They will remain in quarantine in the inside areas until the end of December, though they will be on public display from Monday, December 14. At the end of their quarantine period, they will be allowed outside. Adelaide Zoo director of conservation Kevin Evans said the pandas were settling in well. "They've done really well, much better than we were expecting. If you look at the keepers and the vets who accompanied them on the trip over, they're suffering from serious jetlag, but the pandas seem to have coped much better. "They're munching away on homegrown bamboo. we thought we'd have to gradually ease them on to the Aussie stuff, but they've taken to it right away. They just love the Aussie tucker." For full story and link to video footage >> Pandemonium over Rare Cub Ping Ping the giant panda's future is anything but black and white. -

San Diego Zoo Panda Gives Birth to 5Th Cub 5 August 2009, by ELLIOT SPAGAT , Associated Press Writer

San Diego Zoo panda gives birth to 5th cub 5 August 2009, By ELLIOT SPAGAT , Associated Press Writer that I would know, but she didn't have seemingly as much discomfort or moving about as what we've seen in the past," she said. Bai Yun seemed comfortable with the cub and appeared to start nursing about 30 minutes after birth. "She knows she's been there, done that," Sutherland-Smith said. A second fetus had been detected, but it was probably absorbed in the mother's uterus. This image provided by the San Diego Zoo shows a new panda birth, upper right, captured Wednesday Aug. 5, The pink, nearly hairless panda newborn weighed 2009 via a closed-circut camera in the birthing den in the about 4 ounces and is about the size of a stick of zoo in San Diego. It was the fifth birth for mother, Bai butter. Its gender won't be known for several Yun. The sex of the mostly hairless, pink newborn, which weeks, until officials can get a better look, and it is about the size of a stick of butter, will not be known for won't get a name for 100 days, in line with Chinese some time, and it will be approximately one month tradition. before the iconic black-and-white coloration of a giant panda becomes visible. (AP Photo/San Diego Zoo, Ken Mom and cub will lead private lives for the next four Bohn) months or so, but they will appear on the zoo's live Panda Cam, which can be watched online.