Cloning Noah's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Vanishing Species

A Vanishing Species In a gesture intended to improve its strained and often acrimonious relationship with the United States, the Chinese government presented a pair of giant pandas to President Nixon in 1972. Not only did the gift engender warmer diplomatic relations between the two countries, Ling‐Ling and Hsing‐Hsing became instant celebrities, triggering America’s infatuation with giant pandas. Resembling enormous, cuddly, black‐and‐white teddy bears with round, flat faces and large eye patches, giant pandas have become quite popular. Every city with a large zoo wants them because of the crowds they draw. In 1988, for example, the Toledo zoo paid China several hundred thousand dollars to rent a pair of pandas for five months. The public’s desire for zoo tickets and panda‐related products seemed insatiable. The zoo took in over three million dollars and the city estimated that tourists drawn to the attraction brought in over sixty million dollars. Zoos rent giant pandas, most often from China, but also from other American zoos, because the panda population is so limited and their sale is severely restricted by law. According to the best estimates of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), an organization that protects endangered species, fewer than a thousand pandas are left in the wild. There are about 140 pandas in captivity, mainly in China’s research or reserve centers. Giant pandas are indigenous to southeastern China, where a thousand years ago they roamed freely over two million square miles. Now restricted to small enclaves in China, wild pandas inhabit less than a quarter of 1 percent of that area. -

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song: A Portfolio of Recordings and Exegesis Qing (Lily) Chang Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide July 2017 Table of contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements List of tables and figures Part A: Sound recordings Contents of CD 1 Contents of CD 2 Contents of CD 3 Contents of CD 4 Part B: Exegesis Introduction Chapter 1 Historical context 1.1 History of Chinese art song 1.2 Definitions of Chinese contemporary art song Chapter 2 Performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.1 Singing Chinese contemporary art song 2.2 Vocal techniques for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.3 Various vocal styles for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.4 Techniques for staging presentations of Chinese contemporary art song i Chapter 3 Exploring how to interpret ornamentations 3.1 Types of frequently used ornaments and their use in Chinese contemporary art song 3.2 How to use ornamentation to match the four tones of Chinese pronunciation Chapter 4 Four case studies 4.1 The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Shang Deyi 4.2 I Love This Land by Lu Zaiyi 4.3 Lullaby by Shi Guangnan 4.4 Autumn, Pamir, How Beautiful My Hometown Is! by Zheng Qiufeng Conclusion References Appendices Appendix A: Romanized Chinese and English translations of 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix B: Text of commentary for 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix C: Performing Chinese contemporary art song: Scores of repertoire for examination Appendix D: University of Adelaide Ethics Approval Number H-2014-184 ii NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. -

Chapter Ii the Development of China Panda Diplomacy A

CHAPTER II THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHINA PANDA DIPLOMACY This chapter discusses the development of China Panda Diplomacy. The researcher will explain the symbolism of Panda. In the other hand, the researcher will explore the stages of Panda Diplomacy and mentioning the step of the giant Panda loan breeding process. Last but not least, the writer will mention the countries that received the Panda. A. THE SYMBOLISM OF PANDA China was known as one of the oldest ancient in the earth. Besides its famous landmark of the Great Wall, China owns a cute animal named the Giant Panda, Ailuropoda Melanoleuca (Xianmeng Qiu, Susan A. Mainka, 1993). From the Chinese perspective, Panda is a symbol of peace and friendship. They have a gentle temperament and aren’t known for attacking others. This animal is also believed to have powers to combat evil spirits (Wang, 2017). There some province in China assumes that giant panda is a symbol of luck. The color contrast of giant panda equated as the mythology of Yin and Yang or means as equality that reflected the equality of life. The Pandas are seen as a symbol of co- operation between China and the receiving countries (Hinderson, 2017). Scholars acknowledge that culture is as important a politics, military, and economic as an element in influencing the development of a nation’s foreign policy (Hu, 2013). Buckingham, et al. (2013) stated that the Panda represents a fascinating soft-power resource. The panda offers a softer animal symbol for China compared to those of its past – the red dragon- and it is dealing with the natural beauty of the country. -

US Zoo to Return Beloved Giant Pandas to China 27 March 2019

US zoo to return beloved giant pandas to China 27 March 2019 The species was threatened with extinction when the zoo teamed up with China 25 years ago as part of a conservation program. Today, pandas are listed as a vulnerable species. That means that while their survival is still threatened, conservation efforts have helped reduce their danger of extinction. "We understand that pandas are beloved around the world, including by our staff, volunteers and millions of annual guests," said San Diego Zoo director Dwight Scott. "We are planning a fitting celebration next month Female panda Bai Yun (R) and male panda Gao Gao (L) for Bai Yun and Xiao Liwu that includes a big thank view each other through a screened gate between their you to the Chinese people for their continued exhibits on April 15, 2011 at the San Diego Zoo partnership and our combined conservation accomplishments in helping to save this amazing species." Two giant pandas that have been a star attraction © 2019 AFP at the San Diego Zoo for decades will soon be returned home to China, officials announced. Bai Yun, the 27-year-old female giant panda, and her son, six-year-old Xiao Liwu, will be repatriated to their ancestral homeland in late April. "Although we are sad to see these pandas go, we have great hopes for the future," Shawn Dixon, chief operating officer for San Diego Zoo Global, said in a statement issued Monday. "Working with our colleagues in China, San Diego Zoo Global is ready to make a commitment for the next stage of our panda program." The pandas had been on loan to the zoo as part of a long-term conservation agreement that is coming to an end. -

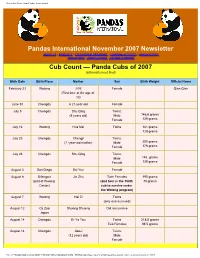

November News from Pandas International

November News from Pandas International Pandas International November 2007 Newsletter ABOUT US :: PRODUCTS :: EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS :: LEARNING ACTIVITIES :: PANDA PHOTOS DONATE NOW :: ADOPT A PANDA :: BECOME A MEMBER Cub Count — Panda Cubs of 2007 (information not final) Birth Date Birth Place Mother Sex Birth Weight Official Name February 23 Wolong Ji Ni Female Qian Qian (First time at the age of 13) June 30 Chengdu A 21-year-old Female July 5 Chengdu Shu Qing Twins: (8 years old) Male 146.5 grams Female 129 grams July 16 Wolong Hua Mei Twins 161 grams 129 grams July 23 Chengdu Chengji Twins: (7 -year-old mother) Male 200 grams Female 176 grams July 23 Chengdu Shu Qing Twins: Male 146. grams Female 129 grams August 3 San Diego Bai Yun Female August 6 Bifengxia Jin Zhu Twin Females 190 grams (part of Wolong (2nd twin is the 100th 70 grams Center) cub to survive under the Wolong program) August 7 Wolong Hai Zi Twins (only one survived) August 12 Oji Zoo Shuang Shuang Did not survive Japan August 14 Chengdu Er Ya Tou Twins 218.5 grams Two Females 98.5 grams August 14 Chengdu Jiaozi Twins: (12 years old) Male Female file:///**WORKING%20FOLDER/**CURRENT%20WORK/PAND...TTERS/2007/November%202007/nov07-newsletter.html (1 of 6)10/26/07 3:17 PM November News from Pandas International August 18 Wolong Gong Zhu Twins: 168 grams Males 179 grams August 23 Schoenbrunn Yang Yang Twins 3.5 ounces Zoo, Vienna, (first time mother) (only one survived) 3.9 inches Austria August 24 Wolong Long Xin Twins September 14 Wolong Ye Ye Twins Breeding pens at Wolong Suzanne Braden with Qing Qing, first cub of 2007, in July 2007. -

2017 Breeding Recs Final ENGLISH.Pdf

Report to: Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens (CAZG) Giant Panda Office, Department of Wildlife Conservation, State Forestry Administration Giant Panda Conservation Foundation (GPCF) 2017 Breeding and Management Recommendations and Summary of the Status of the Giant Panda Ex Situ Population 8 - 9 November 2016 Chengdu, China Submitted by: Kathy Traylor-Holzer, Ph.D. IUCN SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group Jonathan D. Ballou, Ph.D. Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute Chinese translation provided by: Yan Ping, Giant Panda Conservation Foundation Sponsored by: Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens Executive Summary This is a report on the meeting held 8-9 November 2016 in Chengdu, China to update the analysis of the ex situ population of giant pandas and develop breeding recommendations for the 2017 breeding season. This is the 15th annual set of genetic management recommendations developed for giant pandas. The current ex situ population of giant pandas consists of 470 animals (212 males, 258 females) located in 85 institutions worldwide. In 2016 there were 64 births and 16 deaths as of 4 November. Transfers included 100 separate transfers of 88 animals between Chinese institutions and 2 transfers to South Korea. The genetic status of the population is currently healthy (gene diversity = 97.45%), with 53 founders represented and another 7 that could be genetically represented if they were to produce living offspring. There are 6 inbred animals with estimated inbreeding coefficients > 6% and another 25 animals with lower levels of inbreeding. There are 45 giant pandas in the studbook that are living or have living descendants with sires that are uncertain (due to natural mating and/or artificial insemination with multiple males). -

Aaa Panda Is Born Mongolian Mummies Lighthouse Postcards

3 aaa panda is born 6 mongolian mummies 8 lighthouse postcards Smithsonian Institution SCIENCE, HISTORY AND THE ARTS NUMBER 11 · WINTER 2006 smithsonian online Electricity on film. Since the 1930s, the distinctive images disseminated by the Wash- ington, D.C.-based organization Science Service have captured the attention of newspa- per and magazine readers worldwide. These sci- ence-focused images and their concise captions helped forge a broader understanding and appreci- ation of the many scientific and technological number 11 · winter 2006 achievements made in the last 80 years. A new Web site from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Published quarterly by the Smithsonian Office of Public Affairs, Smithsonian Institution American History features an eye-grabbing selec- Building, Room 354, MRC 033, P.O. Box tion of Science Service images related to electricity 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, for and dating from the 1930s to the 1960s. Accompa- Smithsonian Contributing Members, scholars, nied by their original captions, the photos in this educators, museum personnel, libraries, online archives are presented exactly as they ap- journalists and others. To be added to the mailing list or to request this publication in peared in period publications. Organized under an accessible format, call (202) 633-5181 dozens of subject headings, such as batteries, ca- (voice) or (202) 357-1729 (TTY). bles, cameras, computer art, lighting, electron John Barrat, Editor tubes, fiber optics, fire alarms, lasers, recordings, stratovision and television, this Web site is a visual Colleen Perlman, Assistant Editor primer on the development and application of Evelyn S. Lieberman, Director of electronics in modern life. -

2019 Breeding and Management Recommendations and Summary of the Status of the Giant Panda Ex Situ Population

Report to: Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens (CAZG) Giant Panda Office, Department of Wildlife Conservation, State Forestry Administration Giant Panda Conservation Foundation (GPCF) 2019 Breeding and Management Recommendations and Summary of the Status of the Giant Panda Ex Situ Population 8 - 9 November 2018 Chengdu, China Submitted by: Kathy Traylor-Holzer, Ph.D. IUCN SSC Conservation Planning Specialist Group Jonathan D. Ballou, Ph.D. Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute/ Species Conservation Toolkit Initiative Chinese translation provided by: Yan Ping, Giant Panda Conservation Foundation Sponsored by: Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens Executive Summary This is a report on the meeting held 8-9 November 2018 in Chengdu, China to update the analysis of the ex situ population of giant pandas and develop breeding recommendations for the 2019 breeding season. This is the 17th annual set of genetic management recommendations developed for giant pandas. The current ex situ population of giant pandas consists of 548 animals (249 males, 299 females) located in 93 institutions worldwide. As of 8 November181 animals were transferred in 2018, including 4 from China to institutions outside of China and 4 between institutions in Canada. The genetic status of the population is currently healthy (gene diversity = 97.59%), with 58 founders represented and another 4 that could be genetically represented if they were to produce living offspring. There are 9 living inbred animals with estimated inbreeding coefficients > 6% and another 39 animals with lower levels of inbreeding. There are 66 giant pandas in the studbook that are living or have living descendants with sires that are uncertain (due to natural mating and/or artificial insemination with multiple males). -

October 2007 News from Pandas International

October 2007 News from Pandas International Pandas International October 2007 Newsletter ABOUT US :: PRODUCTS :: EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS :: LEARNING ACTIVITIES :: PANDA PHOTOS DONATE NOW :: ADOPT A PANDA :: BECOME A MEMBER This newsletter will focus on two stories of individuals who Note: Due to traveling to China, major health problems, volunteered at Wolong this year, their thoughts, their and an auto accident, we have not gotten out our monthly experience, and their love for pandas. newsletters. If you are interested in volunteering check our web site http:// We have so much to tell you about Suzanne’s trip to www.pandasinternational.org/volunteer.html Wolong, the new cubs at Wolong and various other panda stories, we will send two newsletters a month till we get you caught up on all the news.! Our Summer Vacation The giant panda cub who by Rebecca & Richard Johnston, Wolong Volunteers didn’t make it, but left a As frequently and most aptly stated by panda keepers at the legacy of love San Diego, CA Zoo, I too have been having a love affair with the Giant Panda for some time now. Not since 1987 as in the by Chet Chin, Wolong Volunteer and Panda Parent case of the San Diego Zoo, but since 1999 when Hua Mei, When he was born, he made headlines around the world, not born in San Diego of parents Bai Yun and Shi Shi, received just because he was a giant panda cub, but because he was the title of “first panda to be born and survive to adulthood in the first giant panda cub to be born with a harelip. -

Frozen Zoo May Hold Hope for Saving the Northern White Rhino

Frozen Zoo may hold hope for saving the northern white rhino By TONY PERRY JANUARY 23, 2015, 7:07 PM | REPORTING FROM SAN DIEGO ola is eating her morning meal of apples and grain and appears ready to take her N antibiotic pills. After feeling poorly for a couple of weeks, she is moving around. This is welcome news to Nola's devoted keepers at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. She is one of only five northern white rhinos left on Earth: three of the others are in a preserve in Kenya, and one is in a zoo in the Czech Republic. Nola's recent illness, coming just weeks after the unanticipated death of Angalifu, the park's male northern white rhino, was a pointed reminder of the fragility of her species. At 40, even with care, Nola is near the end of her expected life span, and breeding is no longer seen as an option. Efforts in Kenya to mate the male and the two females have been unsuccessful. But scientists working for the zoo's Institute for Conservation Research say hope may yet exist for the northern white rhino: futuristic technology that might allow it to make a comeback even after the remaining animals are gone. The strategy — a long shot, researchers acknowledge — involves frozen specimens of reproductive material and a surrogate rhino mother from a different subspecies. "You have to be optimistic, but you have to be willing to accept that you're going to fail sometimes," said Barbara Durrant, director of reproductive physiology at the institute. -

Pandas International September 2009 Newsletter

Pandas International September 2009 Newsletter You're receiving this announcement because you have signed up as a Panda Pal. Not interested anymore? Unsubscribe. Having trouble viewing this email? View it in your browser . DONATE NOW :: ADOPT A PANDA :: SPONSOR A PANDA :: BECOME A MEMBER Some original material reprinted by Pandas International's Newsletter is used without editing for accepted English usage. Summer, a time of births and birthdays San Diego Zoo's giant panda, Bai Yun, gives birth to a healthy cub Just before 5 a.m. on August 5, 2009, Bai Yun gave birth to what the zoo's senior research technician Suzanne Hall called a "vigorous, squawking" cub. For about 24 hours prior to the birth, Bai Yun had been restless, alternating between sleep and bouts of nest-building, Hall wrote on the zoo's blog. The cub's gender is not yet known. Bai Yun (seen here in an archived photo) Bai Yun is described by zoo staff as an is proving to be a great mother once again. excellent, attentive mother; she's given birth Read the complete story >> to four other cubs (Hua Mei, Mei Sheng, Su Lin and Zhen Zhen) since arriving at the zoo See video of cub's birth >> as part of a scientific exchange with China in 1996. Not to be forgotten, Zhen Zhen and Su Lin celebrate their birthdays at the San Diego Zoo Giant pandas Zhen Zhen and Su Lin celebrated their birthdays at the San Diego Zoo Monday, August 3rd, with tiered ice cakes filled with their favorite treats -- apples, carrots and bamboo. -

Marines Landed on Iwo Jima Feb. 19, 1945 “Uncommon Valor Was a Common Virtue” -- Adm

7:50 PM r 94 min Monday - February 24, 2020 5:40 PM Base Movie Schedule AutoMatters & More The Gentlemen, The Last Full Measure, Going on safari at the San Your FREE Dolittle, Bad Boys For Life, Just Mercy, Diego Zoo & Safari Park. The Grudge. weekly paper See page 12 See page 13 Take one! Navy Marine Corps Coast Guard Army Air Force ARMED FORCES DISPATCHSan Diego Navy/Marine Corps Dispatch www.armedforcesdispatch.com 619.280.2985 FIFTY NINTH YEAR NO. 43 Serving active duty and retired military personnel, veterans and civil service employees THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2020 MARINES LANDED ON IWO JIMA FEB. 19, 1945 “UNCOMMON VALOR WAS A COMMON VIRTUE” -- ADM. CHESTER NIMITZ by David Vergun, was standing beside Rosenthal, 1949 “Sands of Iwo Jima,” star- DOD News captured the same moment on ring actors John Wayne and For- By February 1945, U.S. forces video. Genaust was killed nine rest Tucker, and two 2006 movies had island hopped across the days later. directed by Clint Eastwood: “Let- Pacific Ocean and were rap- ters from Iwo Jima” and “Flags of idly closing in on the Japanese The image of the flag raising Our Fathers.” mainland. was so powerful that it was fea- tured on a U.S. postage stamp, and The U.S. returned Iwo Jima to Before attacking Japan, war a large statue of the flag raising is Japanese control in 1968. Today, planners hoped to capture Iwo featured at the Marine Corps War the Japan Maritime, Ground and Jima, a tiny island in the West- Memorial in Arlington, Va.