A Play with Ajax, Philoctetes, Sassoon, and Owen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harrow Council School Travel Plan Strategy

Draft HARROW COUNCIL SCHOOL TRAVEL PLAN STRATEGY 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................. 2 2.0 MAIN PROBLEMS AND OPPORTUNITIES.................................... 3 2.1 The School Run and Car Use ...................................................... 3 2.3 Walking to School ........................................................................ 4 2.4 Parental Safety Concerns ............................................................ 4 2.5 Parental Choice for school admission.......................................... 4 3.0 PAST AND ONGOING INITIATIVES TO ADDRESS PROBLEMS.. 5 3.1 Safe Routes to School Programme.............................................. 5 3.2 Road Safety Education ................................................................ 5 3.3 Council’s Provision of School Transport ...................................... 6 4.0 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES................................................................ 6 5.0 STRATEGY ..................................................................................... 7 5.1 Development of School Travel Plan (STP) and Related Measures . 7 6.0 IMPLEMENTATION PROGRAMME.............................................. 10 6.1 Setting up a School Travel Plan................................................. 10 Draft 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 There is an increasing problem with the number of children who are taken to and from school by car. Over the last few years, car use on the school run has increased causing traffic congestion, increased pollution, -

Twenty-One Years of Grant-Giving in North West London 1992-2013

Twenty-one years of grant-giving in north west London 1992-2013 Annual Report 2013 Members and Advisers About John Lyon’s Charity Financial Highlights 2013 THE TRUSTEE ADVISERS TO THE CHARITY Who was John Lyon? Who governs the Charity? The Keepers and Governors of the Possessions Sandy Adamson CBE A yeoman farmer from Harrow who, in 1572 The Governors of Harrow School are the Revenues and Goods of the Free Grammar School Katie Argent was granted a Royal Charter by Elizabeth I Trustee of John Lyon’s Charity. They have of John Lyon Susan Ferleger Brades to found a free grammar school for boys: appointed a Grants Committee to oversee Father Andrew Cain Harrow School. The Charter anticipated that the grants programme and recommend MEMBERS OF THE CORPORATION Michael Coveney John Lyon would establish a separate trust awards for their approval. The Charity remains as at 31 March 2013 Teresa Gleadowe for the purpose of maintaining two roads independent from the two schools. Julia Kaufmann OBE from London to Harrow, now the Harrow and RC Compton DL Chairman Martyn Kempson Grants awarded Edgware roads. In 1578 John Lyon provided JP Batting MA FFA Deputy Chairman Fiona Mallin-Robinson What is the Charity’s policy? an endowment in the form of a farm of some Professor P Binski MA PhD FBA Harry Marsh 48 acres in the area now known as Maida Vale To promote the life-chances of children Mrs HS Crawley BA Abdul Momen and young people through education. Total number of grant requests 241 DA Crehan BSc BA MSc ARCS CPhys Martin Neary LVO for that purpose. -

FNWL 132 Oct 2019

IN THIS ISSUE Education Special issue! It’s time for Nursery or Pre-School! Choosing the right school for your child School Open Days Issue 131 October 2019 familiesonline.co.uk Welcome to the October issue! CONTACT US: Families North West London Magazine WATFORD BUSHEY Editors: Heather Waddington andRI CKJanineMANSWO RTMerglerH M1 P.O. Box 2378, Watford WD18 1RF STANMORE M25 HATCH END NORTHWOOD T: 01923 237 004 E: [email protected] EDGWARE HARROW WEALD HAREFIELD PINNER KINGSBURY Listings and Features Editor: HARROW WEST RUISLIP HENDON Anna Blackshaw E: [email protected] ICKENHAM DOLLIS HILL SUDBURY PARK www.FamiliesNWLondon.co.uk NORTHOLT BRONDESBURY PARK WEMBLEY UXBRIDGE A40 QUEENS PARK WILLESDEN www.facebook.com/FamiliesNWLondon KILBURN @FamiliesNWLon Readership of over 60,000 local parents, carers and teachers every issue. Published seven times a year. For families from birth to twelve. UPCOMING ISSUES: Nov/Dec 2019 - Seasonal Celebrations Deadline 10 October 2019 Jan/Feb 2020 - Nurseries and Childcare Deadline 1 December 2019 Send in your news, stories and advertising bookings to the details above. Feature images used under license from depositphotos.com. IN THIS ISSUE: Other images have been supplied by independent sources. 4 Susie Ramroop – choose your words carefully 5 It’s time for Nursery or Pre- Families North West London Magazine is part school! of Families Print Ltd, a franchise company. 6 Open Days All franchised magazines in the group are independently owned and operated under 7 Choosing the right school licence. Families is a registered trademark of LCMB 8 Meet the Head Teachers Ltd, Remenham House, Regatta Place, Marlow Road, Bourne End, Bucks SL8 5TD. -

LONDON BOROUGH of HARROW MAYORAL ENGAGEMENTS 14 November 2013

LONDON BOROUGH OF HARROW MAYORAL ENGAGEMENTS 14 November 2013 I have carried out the following engagements since the Council Meeting on Thursday 4th July 2013:- 5 July 2013 Attended North Harrow Community Partnership Event Attended Flash Musicals Film Night 7 July 2013 Attended Fetes de Gayant, Douai France 8 July 2013 Attended The John Lyon School’s Speech Day at Harrow School 9 July 2013 Hosted Reception Attended Community Health & Wellbeing Directorate’s Dementia Awareness Certificate 10 July 2013 Presentation in Civic Centre Attended HYM’s Steel/Junior Steel Concert 11 July 2013 Attended Citizenship Ceremony Attended Harrow & Wealdstone District Scout Council’s AGM 13 July 2013 Attended A Donor Recruitment’s Delete Blood Cancer Event Attended St Joseph’s Care Home’s 10 th Anniversary Celebration & Summer Fete Attended Grenada’s 5 th Annual Grenadian Heritage Day at Old Lyonian sports & Social Club in Pinner View Attended Mr Bill Brignell’s 90 th Birthday Celebration at Stanmore Baptist Church Attended Tamil School Hendon’s Annual Prize Giving Day in Canons High School 16 July 2013 Attended Mr Alfred E Porter’s 100 th Birthday Celebration at Paxfold House Attended UK Asian Women’s Conference’s Sports Day for People with Learning Disabilities 17 July 2013 and Social Needs in Pinner Road Attended Harrow Housing Asset Management Team’s Open Day at Civic Centre Attended Shia Ithnasheri Community of Middlesex’s Ramadan Prayers & Iftar Party in North Harrow Assembly Hall 18 July 2013 Attended Citizenship Ceremony Attended North West London -

Appendix - 2019/6192

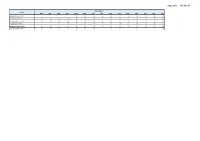

Appendix - 2019/6192 PM2.5 (µg/m3) Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Background Inner London 16 16 16 15 15 14 13 13 13 12 n/a Roadside Inner London 20 19 19 19 18 18 18 17 17 17 16 16 15 15 n/a Background Outer London 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 13 13 13 12 12 11 n/a Roadside Outer London 15 16 17 17 18 17 17 16 15 14 13 12 n/a Background Greater London 14 14 14 14 15 15 15 14 14 14 13 13 12 12 n/a Roadside Greater London 20 19 17 18 18 18 18 17 17 16 16 15 14 13 n/a Appendix - 2019/6194 NO2 (µg/m3) Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Background Inner London 44 44 43 42 42 41 40 39 39 38 37 36 35 34 n/a Roadside Inner London 68 70 71 72 73 73 73 72 71 71 70 69 65 61 n/a Background Outer London 36 35 35 34 34 34 33 33 32 32 32 31 31 30 n/a Roadside Outer London 50 50 51 51 51 51 50 49 48 47 46 45 44 44 n/a Background Greater London 40 40 39 38 38 38 37 36 36 35 35 34 33 32 n/a Roadside Greater London 59 60 61 62 62 62 62 61 60 59 58 57 55 53 n/a Appendix - 2019/6320 360 GSP College London A B C School of English Abbey Road Institute ABI College Abis Resources Academy Of Contemporary Music Accent International Access Creative College London Acorn House College Al Rawda Albemarle College Alexandra Park School Alleyn's School Alpha Building Services And Engineering Limited ALRA Altamira Training Academy Amity College Amity University [IN] London Andy Davidson College Anglia Ruskin University Anglia Ruskin University - London ANGLO EUROPEAN SCHOOL Arcadia -

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012 Organisation Name Total More House School Ltd 5 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE 65 360 GSP College 15 4N ACADEMY LIMITED † 5 E Ltd 10 A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON 20 A+ English Ltd 5 A2Z School of English 40 Abacus College 30 Abberley Hall † Abbey College 120 Abbey College Cambridge 140 Abbey College Manchester 55 Abbots Bromley School for Girls 15 Abbotsholme School 25 ABC School of English Ltd 5 Abercorn School 5 Aberdeen College † Aberdeen Skills & Enterprise Training 30 Aberystwyth University 520 ABI College 10 Abingdon School 20 ABT International College † Academy De London 190 Academy of Management Studies 35 ACCENT International Consortium for Academic Programs Abroad, Ltd. 45 Access College London 260 Access Skills Ltd † Access to Music 5 Ackworth School 50 ACS International Schools Limited 50 Active Learning, LONDON 5 Organisation Name Total ADAM SMITH COLLEGE 5 Adcote School Educational Trust Limited 20 Advanced Studies in England Ltd 35 AHA International 5 Albemarle Independent College 20 Albert College 10 Albion College 15 Alchemea Limited 10 Aldgate College London 35 Aldro School Educational Trust Limited 5 ALEXANDER COLLEGE 185 Alexanders International School 45 Alfred the Great College ltd 10 All Hallows Preparatory School † All Nations Christian College 10 Alleyn's School † Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education † ALPHA COLLEGE 285 Alpha Meridian College 170 Alpha Omega College 5 Alyssa School 50 American Institute for Foreign Study 100 American InterContinental University London Ltd 85 American University of the Caribbean 55 Amity University (in) London (a trading name of Global Education Ltd). -

Brochure 101374004098.Pdf

LOCATION Contents LOCATION Introduction An invaluable insight into your new home This Location Information brochure offers an informed overview of Pinner Road as a potential new home, along with essential material about its surrounding area and its local community. It provides a valuable insight for any prospective owner or tenant. We wanted to provide you with information that you can absorb quickly, so we have presented it as visually as possible, making use of maps, icons, tables, graphs and charts. Overall, the brochure contains information about: The Property - including property details, floor plans, room details, photographs and Energy Performance Certificate. Transport - including locations of bus and coach stops, railway stations and ferry ports. Health - including locations, contact details and organisational information on the nearest GPs, pharmacies, hospitals and dentists. Local Policing - including locations, contact details and information about local community policing and the nearest police station, as well as police officers assigned to the area. Education - including locations of infant, primary and secondary schools and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for each key stage. Local Amenities - including locations of local services and facilities - everything from convenience stores to leisure centres, golf courses, theatres and DIY centres. Census - We have given a breakdown of the local community's age, employment and educational statistics. David Conway 269 Northolt Road, HA2 8HS 020 8422 5222 [email protected] -

Parent Guide to Music Education Andrew Stewart and Christopher Walters 2018–19

PARENT GUIDE TO MUSIC EDUCATION 2018–19 622681 ISBN 9781910622681 781910 9> PGME1819_001_Cover.indd 1 26/07/2018 17:27 Junior Academy Beginners’ courses (ages 4–6) Junior Academy (ages 13–18) Primary Academy (ages 8–12) Junior Jazz (ages 14–18) We offer outstanding opportunities for The Director, Howard Ionascu, is always happy talented and committed young musicians. to meet and discuss Junior Academy with Our Saturday programme includes individual prospective students and parents. tuition, chamber music, orchestras, choirs, theory, aural, composition classes and many performance opportunities. www.ram.ac.uk/juniors PGME1819 NEW.indd 2 01/08/2018 16:36:23 CONTENTS GETTING STARTED 6 FURTHER & HIGHER EDUCATION 71 Introduction to music learning 6 Higher education choices 72 Contents Contents Buying an instrument 8 LISTINGS Supporting instrument learning 10 Conservatoires 75 Questions for private teachers 11 Universities 88 Questions for open days 12 Universities without Scholarships for 11+ 14 Degree Courses in Music 93 A guide to music hubs 17 Further and Higher Education Colleges 94 Top music departments 18 Teacher Training Courses 98 INSET Courses 100 SPECIALIST SCHOOLS 21 Specialist Courses 101 Specialist schools 22 Summer Schools and Short Courses 108 LISTINGS Scholarships, Grants and Specialist music schools 25 Private Funding Bodies 115 Specialist choir schools 27 EXTRACURRICULAR 121 INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS 31 Junior conservatoires 123 Independent schools round up 32 Extracurricular activities 126 LISTINGS LISTINGS Independent Secondary, Preparatory Extracurricular 129 and Junior Schools 35 First published in 2012 in Great Britain by Rhinegold Publishing Ltd, 20 Rugby Street, London, WC1N 3QZ Tel: 020 7333 1733 © Rhinegold Publishing 2018 Editor Alex Stevens ISBN: 978-1-910622-68-1 Designer/Head of Design & Production Beck Ward Murphy All rights reserved. -

Ranking Reflects Unsettling Times

Top Independent Schools FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Saturday September 10 2011 www.ft.com/independentschools2011 | www.twitter.com/ftreports In this issue Charity inquiry A landmark judgment will determine the public benefits schools must provide Page 2 Value for money Parents may be better off opting for chains rather than the big name schools Page 4 Technology The independent sector has not been left behind in the IT race Page 5 Switching sectors Even the wealthy may consider sending their offspring to staterun schools at some point Page 6 Marketing Schools are increasingly turning to professional persuaders to make sure clients keep coming through the door Page 7 Rankings The FT’s Road to success: Magdalen College School in Oxford has taken first place in the independent school league table this year guide to the UK’s top independent establishments Pages 811 Ranking ref lects unsettling times Pupil development Rounded The different orget Buster private school has not just within England, an ment to compare qualifi- personalities are Douglas beating topped it. Does this mean extremely difficult task. cations. But these are cur- qualifications on Mike Tyson in Westminster has lost its What is the correct rently under review, and part of the offer have added 1990 or Wimble- killer instinct? Well, no. exchange rate to apply there is a suspicion that package Fdon beating Liverpool to Its decline (to sixth place) when comparing results the Pre-U is under- Page to the complexity win the FA Cup in 1988. coincides with its attained in the Interna- weighted in this metric. -

Harrow School

Harrow Local Plan Supplementary Planning Document Harrow School Adopted July 2015 Supplementary Planning Document HARROW SCHOOL July 2015 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 02 2.0 Planning Policy Context 07 3.0 Historical and Present Context 15 4.0 Characteristics of the site 17 5.0 The Masterplan Vision / Achieving the Vision 24 6.0 Design Considerations 36 7.0 Phasing of Development at Harrow School 42 8.0 Monitoring the SPD 44 Appendices A: Harrow School Chronology 45 B: Views 51 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This Supplementary Planning Document has been developed to help Harrow School strengthen its role as a world-class education institution by outlining an agreed masterplan for the development and change of the School Estate over the next 20 years. Such an approach is consistent with the School’s site allocation in the Harrow Local Plan. 1.2 Since its formation in 1572, the School has needed to develop and adapt to meet the demands of its changing academic and accommodation requirements. This need for continual change is no less pressing today. Whilst there is no intention to increase student numbers, in order to maintain the current high standards, the School needs to look forward and to plan for development and change over the next 20 years. 1.3 Much of the existing Harrow School estate has development constraints and is not ideally suited to modern teaching and boarding requirements. New buildings are required that are modern, flexible and adaptable in order that they will remain viable in a continually changing academic environment. The School’s faculty structure requires close inter-relationships and ease of access between specific departments. -

REGISTER of STUDENT SPONSORS Date: 26-April-2021

REGISTER OF STUDENT SPONSORS Date: 26-April-2021 Register of Licensed Sponsors This is a list of institutions licensed to sponsor migrants under the Student route of the points-based system. It shows the sponsor's name, their primary location, their sponsor type, the location of any additional centres being operated (including centres which have been recognised by the Home Office as being embedded colleges), the rating of their licence against each route (Student and/or Child Student) they are licensed for, and whether the sponsor is subject to an action plan to help ensure immigration compliance. Legacy sponsors cannot sponsor any new students. For further information about the Student route of the points-based system, please refer to the guidance for sponsors in the Student route on the GOV.UK website. No. of Sponsors Licensed under the Student route: 1,118 Sponsor Name Town/City Sponsor Type Additional Status Route Immigration Locations Compliance Abberley Hall Worcester Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abbey College Manchester Manchester Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abbotsholme School UTTOXETER Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abercorn School London Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Aberdour School Educational Trust Tadworth Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Abertay University -

Which London School? & the South-East 2018/ 19 the UK’S Leading Supplier of School and Specialist Minibuses

Which London School? & the South-East 2018/ 19 London School? & the South-East Which JOHN CATT’S Which London School? & the South-East 2018/19 Everything you need to know about independent schools and colleges in London and the South-East 29TH EDITION The UK’s Leading Supplier of School and Specialist Minibuses • Fully Type Approved 9 - 17 Seat Choose with confidence, our knowledge and School Minibuses support make the difference • All The Leading Manufacturers • D1 and B Licence Driver Options 01202 827678 • New Euro Six Engines, Low Emission redkite-minibuses.com Zone (LEZ) Compliant [email protected] • Finance Option To Suit all Budgets • Nationwide Service and Support FORD PEUGEOT VAUXHALL APPROVED SUPPLIERS JOHN CATT’S Which London School? & the South-East 2018/19 29th Edition Editor: Jonathan Barnes Published in 2018 by John Catt Educational Ltd, 12 Deben Mill Business Centre, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 1BL UK Tel: 01394 389850 Fax: 01394 386893 Email: [email protected] Website: www.johncatt.com © 2018 John Catt Educational Ltd All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Database right John Catt Educational Limited (maker). Extraction or reuse of the contents of this publication other than for private non-commercial purposes expressly permitted by law is strictly prohibited. Opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors, and are not necessarily those of the publishers or the sponsors. We cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions.